“My Cinema Is Not Diplomatic, It Is Confrontational”: Decolonial Framing of the Home in Two Documentaries by Rosine Mbakam

Julie Le Hegarat

[PDF]

Abstract

This article centers on two documentaries about migrant women in their home: At Jolie Coiffure (Chez Jolie Coiffure,2018) and Delphine’s Prayers (Les Prières de Delphine, 2021), both directed by by Rosine Mbakam. I put in conversation the home as a private space and the home as a national construction which creates categories of exclusion and restrictions. I argue that Rosine Mbakam performs an act of “decolonial framing” by taking an antiethnographic approach and creating documentary events—including the filmmaking process, the film viewing, and real-life interactions centering on the film. This transnational cinema of confrontation creates community for Black, diasporic, and African audiences while reversing the gaze against white audiences. Mbakam films the home to showcase instances of resistance to institutional racism and colonial duress. Showing the home on screen also opens the way to create better homes for all through multiple avenues of participation. First, I analyse Mbakam’s filmmaking process and her own involvement on screen as a co-creative act, I then look at her composition which reflects the complex dwellings of the protagonists and how they are shaped by architecture. Finally, I look at the reception of her films to show how her mobile cinema activities provide the infrastructure for making new home spaces.

Article

Rosine Mbakam’s documentaries At Jolie Coiffure (Chez Jolie Coiffure, 2018) and Delphine’s Prayers (Les Prières de Delphine, 2021) start with gestures of invitation. At Jolie Coiffure follows Sabine, the owner of a small, intimate hair salon. The camera is first positioned outside of Sabine’s business, looking in. A group of men threaten to turn off Mbakam’s camera and Sabine urges the filmmaker to grab her equipment and come inside. A similar gesture opens Delphine’s Prayers. We hear Mbakam’s voice, offscreen. She reassures Delphine, the woman in the frame and sole character for the rest of the documentary, that the film will be edited in her best interest. Delphine is uneasy with the filmmaker’s bodily stance: she tells her to grab a chair and sit down with her to create a more intimate interaction.

Mbakam performs a decolonial gesture by inviting clear reciprocity between the filmmaker and the women on camera, with an “aesthetics of accountability” that “prioritize(s) the relationship of the film to the subjects who appear in it” (Ginsburg 39). These sequences display the trust granted to the filmmaker, the shift of power between her and the protagonists, the intimate connections formed between the women, and by extension, give the audience permission to enter Sabine and Delphine’s homes. Framing her films with these opening sequences, Mbakam exposes the infrastructure of her documentaries and informs us about her process: her filmmaking is relational and she is an active co-participant in Delphine’s and Sabine’s practices of resistance, from home.

Both films follow women who have emigrated from Cameroon to Belgium through exploitative migration networks and trouble the myth of Europe as a welcoming home. Mbakam is attentive to the quotidian gestures of resistance performed by Sabine and Delphine as they live precarious lives, threatened by systemic racism and hostile institutions. Mbakam herself moved from Cameroon, where she worked in video and communication, to pursue film school in Belgium. In Delphine’s Prayers and in a private interview I conducted with her, she evoked how she too has faced discrimination and racism in Belgium. Her documentaries present a complex transnational perspective, inclusive of Cameroon and Africa, exploring how home is both a “here” and a “there”. As Yasmina Price points out in her article drawing on Stuart Hall, “absolutist divisions of ‘the West and the Rest’ are ahistorical simplifications, ultimately functioning to stabilise discourses of the former’s neutrality and superiority” (“On”).In fact, Mbakam’s practice responds to colonial history in cinema. In the African Francophone context, for the first half of the twentieth century, the French colonial administration controlled the kind of content that would be shown in African colonies, forbidding Africans’ access to production, while Belgium established training centres to promote Catholic propaganda (Ukadike 218). Later, France created the Consortium Audiovisuel International (CAI) that assisted newly independent countries in producing newsreel and documentaries, thus contributing to the emergence of the first generation of prominent African filmmakers such as Paulin Soumalou Vieyra and Ousmane Sembène in Senegal, and Cameroonian Jean-Pierre Dikongue-Pipa (219). Women have also long contributed to documentary filmmaking in Africa (Ellerson 224; Tchouaffé 193). For example, Safi Faye, from Senegal, learned under Jean Rouch, studied ethnography in Paris, and came back to make documentaries before moving to fiction. Notably, Cameroonian filmmaker Thérèse Sita-Bella is credited as the first African woman film director with Tam Tam à Paris (1963), a documentary on a Cameroonian group of dancers performing in Paris.

Closer in time to Mbakam, a preoccupation with the effects of colonialism in Africa and in transnational context also traverses the works of Jean-Marie Téno, perhaps the most visible documentary filmmaker from Cameroon in Europe at the moment. Rosine Mbakam’s latest collaborative documentary, Prism (Prisme 2021), addresses racism in filmmaking in Belgium, like Pascale Obolo’s La Fabrique des contre-récits (2021), which showcases racism against Black women in the art world in Belgium. In At Jolie Coiffure and Delphine’s Prayers, filming the home of African migrant women showcases the effects of colonial history on their intimate lives and contributes to creating cinematic representations on their own terms. For the women in these documentaries, home is multi-sited. Talking about the home often implies a journey and a return. Sometimes, one comes back home after a period of absence. Other times, one leaves the homeland to make a new home elsewhere. Some other times, instead, we feel at home when experiencing a sense of familiarity. Home, then, is not only tied to a physical location, it is also an affect. In this context, I thus understand “home” as a physical and metaphorical space of affinity, “domestic” as indicative of the ideology relegating women to dedicated private, national, and sexual categories, and “intimacy” as the various intensities of bodily proximity. My understanding of home, intimacy, and domesticity is therefore not limited to sexuality and reproduction, but expands to include various intensities of closeness and familiarity between individuals, which account for a wider range of public, private, and national interactions.

Intimacy is not always a positive, desired proximity. Sometimes it is rather a violence that opens “embodied and affective injuries of a different intensity” (Stoler, Duress 16). This violence is especially felt by women from the diaspora whose intimacies are shaped by enduring colonialism. Colonial duress does not present monolithic unchanged features, but rather “processes of partial reinscriptions, modified displacements, and amplified recuperations”, which constitute contemporary racism in Western Europe (Stoler, Duress 27). In turn, such duress also shapes the space of the home, creating imaginary and physical borders that produce a complex network of attachments, strictures, and exclusions. Feminist theory in Western Europe has also challenged the popular assumption that the domestic is a private space remote from the public and outside the political arena. What is more, speaking specifically to African contexts, Susan Andrade, in The Nation Writ Small, has shown that art made from the home, about the domestic, has instead been a space for political contestation and the articulation of resistance.

Meanwhile, in Western Europe, enduring colonial discourse and ideologies on what constitutes the national domestic space creates interior frontiers excluding migrants and racialised populations from feeling at home (Stoler, Interior Frontiers 60). The domestic is thus shaped by cultural and institutional narratives that imagine the national spaces in Western Europe as racially white and built in opposition to the perceived foreign. Such public discourse and institutional cruelty also seep into the private, shape the feeling of being at home, and structure the spatiality of daily life. For instance, as I will further discuss, in these two documentaries, both Delphine and Sabine inhabit small spaces, encircled by the violence of white supremacy that constantly threatens their homes. In the case of Delphine, who lives with her older white Belgian husband in a marriage of convenience, their shared house is structured by the colonial nature of their relationship which spatially regiments her own life.

To understand the role played by the home and the resistance performed by the protagonists of At Jolie Coiffure and Delphine’s Prayers, I analyse what I call “decolonial framing”. I argue that decolonial framing shifts the discourse on African women in Europe and in Africa. It also asks us to look differently and examine the home as a site of social and political articulation. Home and the domestic are a fragmented and disseminated space that offers multiple entrances for individuals—in the moment of filmmaking, in the image itself and in public discussions. This reading invites us to look at the material conditions of filmmaking and its reception.

First, I contextualise the films within broader conversations on migration, diaspora, and gender. I use the framework of precarious diasporic intimacies to analyse Mbakam’s decolonial practices in the moment of filmmaking. Mbakam reframes the conversation on African migrant women by adopting aesthetic, narrative and ideological strategies that give them the opportunity to speak on their own terms. By doing so, she opposes the history of colonial documentaries about Black African women. She adopts a position that is anti-ethnographic and against postures of mastery. As such, she also reframes the role of the filmmaker, who is both at the service of the protagonists and a participant in their experience. By focusing on the intimate lives of women and how they experience their diasporic home every day, Mbakam requires us to pay attention to the ways in which colonial duress impacts our homes, simultaneously showing the hardships faced by the women, their active resistance, and the glimpses of joy they find in community. Secondly, focusing on composition, I show how Mbakam creates a decolonial aesthetic that is inscribed in the image itself as she mirrors the domestic space as a “dwelling”—understood as a place of residence, a temporality and an affect. Mbakam sets her camera within four walls to illustrate how our living spaces shape our experience. But our living spaces are porous and always conditioned by larger social and material factors. Like film, architecture is a “framing activity” that structures experience and shapes how we look in narrative, ideological and cultural terms (Rascaroli 138–39, 280). Cinematic framing of details of interior architecture shows how it conditions the human experience, all at once offering a sense of privacy but also limiting the dweller into a space constantly susceptible to violations (146). Finally, I discuss audiences and mobile infrastructures, showing how the films exceed the cinematic frame to become documentary events. Mbakam provokes confrontations for her spectators, bringing African audiences to face the realities of migration and challenging white audiences in their racism. Decolonial framing then delocalises the home, de-anchoring it from a dedicated place to imagine it as a multifaceted space instead. As the physical domestic space of the home is unstable for the women (threatened by patriarchy, colonial racism, and the dangers of undocumented living), Mbakam’s practice and aesthetics foster cultural affinities that create a pluriform diasporic domestic space.

Figure 1: Life in Sabine’s salon. At Jolie Coiffure (Chez Jolie Coiffure).

Directed by Rosine Mbakam. Tândor Productions, 2018. Screenshot.

Framing Intimate Encounters

At Jolie Coiffure, released in 2018, is set in Sabine’s small hair salon located in the Matongé neighbourhood in Brussels. The film documents Sabine’s daily life and her interactions with employees, patrons, and other shopkeepers of the commercial gallery. The camera lingers on her as she performs the quotidian, intimate gestures of doing hair while talking about love, relationships, immigration, and racism. Leaving Cameroon for Lebanon, initially lured in by the promise of work and a better situation, Sabine was enslaved but managed to break free and eventually set up on a perilous journey to Europe by foot, led by smugglers. Sabine is undocumented in Belgium, and the film follows her and her peers through some of their many hurdles to obtain documentation. The film never shows her private residence, staying inside the salon instead. It is a meeting place where women share desired intimacies, a quasi-domestic space where they experience beauty together, in physical and emotional proximity. Many documentaries made by African women from the diaspora or located on the continent have explored how beauty is crucial to the expression of identities, especially as it pertained to hair, skin, and the body (Ellerson 18). Eventually, in the film, the salon becomes like another home, produced by the conditions of diaspora, where women can find community and comfort amidst a national domestic space that marginalises them.

Delphine’s Prayers features Mbakam’s long-time friend Delphine, who also made the journey from Cameroon to Belgium. Set in Delphine’s living bedroom, the film is composed of different meetings between her and Mbakam. A true griot, Delphine performs cinematic storytelling facing the camera, deciding what she wants to share, and when she wants to end for the day. Delphine grew up poor, in a small village in Cameroon where she was raped at the age of thirteen. Pregnant from this crime, she turned to sex work to support herself and her family members, who eventually rejected her. Delphine cumulated odd jobs until an older white man asked her to marry and join him in Belgium. Once in Europe, Delphine is confronted with social and institutional racism and makes sacrifices for her children. Like Sabine’s, Delphine’s testimony ultimately undermines the myth of salvatory migration to Europe, showing instead the mechanism that perpetuates racism and colonial duress. The film closes first with a sequence of Delphine performing a prayer and then with a scene in which she braids Rosine’s hair. During this intimate scene, Mbakam, in voiceover, pays homage to her friend, acknowledging the colonial and racist forms of oppression that brought them close in Belgium, as well as their different trajectories and class positions in Cameroon.

These new interactions constitute a “diasporic intimacy”, a closeness produced by the conditions of diaspora (Boym 499). It is experienced between Rosine and Delphine, who come from different classes, and by the patrons of diverse African origins in Sabine’s salon. In the film, she recalls how, when she first arrived in Brussels, she looked for the African neighbourhood, feeling like there is one in every big European city—like a home away from home. Sabine finds closeness with friends and customers at the salon, invites new friends to join her tontine and helps her male friend fix his marriage.[1] But, as showcased in a crucial sequence in At Jolie Coiffure, violence always looms as police officers regularly raid the mall to arrest undocumented workers. These intimacies are therefore precarious and call for “aesthetic strategies that highlight moments of intimacy and the political possibilities they unfold, while also uncovering the structures of violence in which they are embedded” (Stehle and Weber 5).

Figure 2: Sabine’s shop is closed during the police raid. At Jolie Coiffure. Screenshot.

For Sabine and Delphine, testifying constitutes a decolonial gesture of protest. Mbakam is at the service of Sabine and Delphine. Both summoned the documentarian to use the filmic medium to reverse the white, colonial gaze; what Yasmina Price called “an example in shifting the power structures of filmmaking” (Price, “On”). In response to enduring colonial practices in documentary films about the domestic lives of African women, Mbakam’s filmmaking is anti-ethnographic. Her camera holds a value of indexicality, observing and recording life in the salon, her presence included, but her posture is not one of distance.

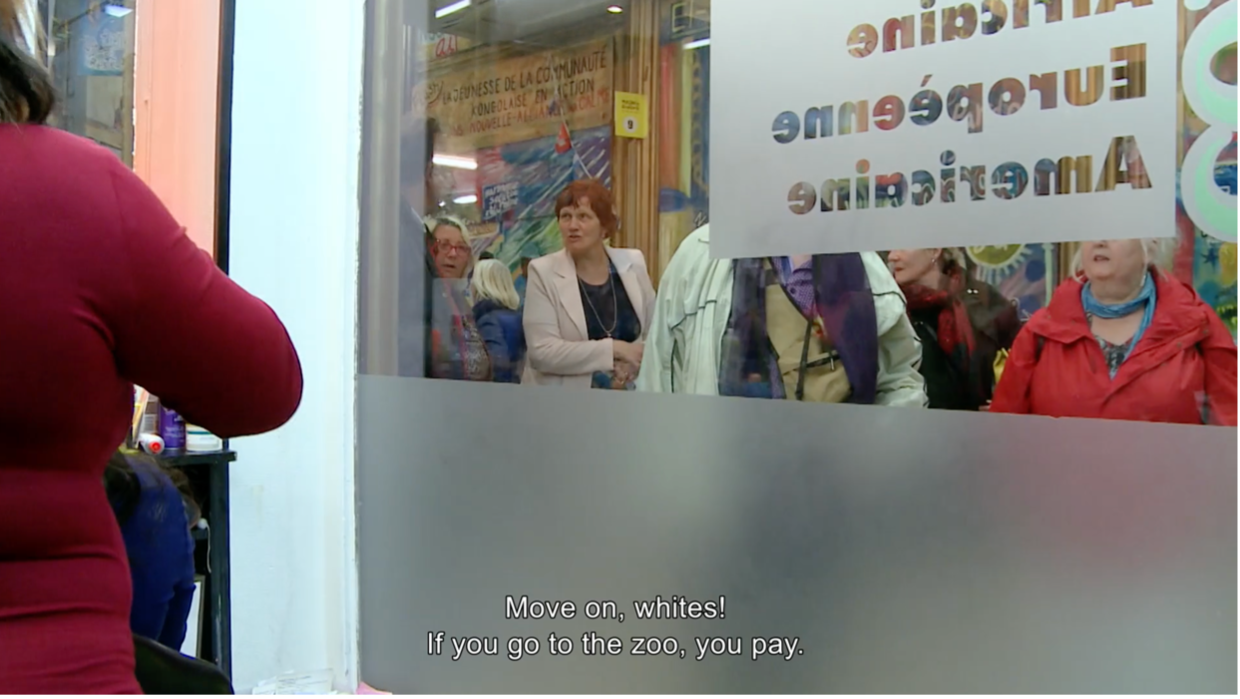

One scene in At Jolie Coiffure illustrates this co-creative act, exhibiting intimacies, desired or not, experienced by Sabine together with the potential for practising decolonial gestures in the act of filming. In the foreground, we see Sabine working on a client while hordes of white passers-by with amused faces visit the shopping gallery. They stare inside her salon, their racism vaguely disguised as cultural interest and local tourism. Sabine comments that they peer into her salon like a zoo. To reverse the colonial gaze, Sabine asks Rosine to point the camera at them so they can see what it feels like to be captured by a scrutinising gaze. This moment calls to mind the history of centuries of European exploitation and enslavement with “cultural exhibitions” and human zoos. For Belgium, it is a not-so-distant past. The Exposition Universelle held in Brussels in 1958 featured such human zoos supposed to recreate the life of a Congolese village. Congo, still a Belgian colony at the time, obtained its official independence two years later.

Figure 3: Sabine asks Rosine to use her camera to reverse the gaze. At Jolie Coiffure. Screenshot.

Mbakam’s decolonial approach to documenting shapes a space that rejects pretensions to neutrality or objectivity while committed to recording the real-life material conditions affecting Black migrant women in Europe. In the face of lack of financing, institutional support through school and access to infrastructure, Mbakam decided to seize a camera and shoot. Both documentaries were filmed with one single camera, by Mbakam alone. For Brian Larkin, “infrastructures are built networks that facilitate the flows of goods, people, or ideas and allow for their exchange over space” (“Politics” 328). For some scholars, infrastructures are invisible; for others, they are rather so omnipresent that their hypervisibility goes unnoticed. It is only when things do not work, in the moment of “glitch” that infrastructures manifest to us (Berlant 393), revealing their full organisational power. In Mbakam’s documentaries, this disparity of power and the lack of infrastructure is deliberately visible on screen, making the glitch an integral part of the film. The editing, done by Mbakam’s collaborator Geoffroy Cernaix, rejects post-production stylisation and keeps “imperfect” moments that further showcase the conditions of production of the film to reveal the failures of infrastructure in the image itself. In this sense, Mbakam and Cernaix are aligned with fellow Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman when she said in an interview that “form highlights class struggles within the image itself” (Treilhou 91, my trans.).

The moment of filmmaking opens a space to collectively practice decolonial strategies within the home, including attempts, frustration, discursive hesitations, or filmic “mistakes”, some of which were intentionally kept during the editing. Namely, Rosine inadvertently appears in one of the shots in the salon, displaying the apparatus of the camera. As she pans right and left, trying to conceal the camera, the editing maintains this moment of hesitation, foregrounding her presence in the intimate space as well as the challenges of unsupportive infrastructures. In Delphine’s Prayers, the editing similarly keeps “imperfect” moments, as the camera shakes while Rosine laughs or as she readjusts her camera for better framing for example. In this sense, her cinema exhibits some of the features of an anti-ethnographic cinema listed by Trinh T. Minh-ha: “split faces, bodies, actions, events, rhythms, rhythmized images, […] framing and reframing, hesitations; […], snatches of conversations, cuts, broken lines, words; repetitions; silences; […] a look for a look; questions, returned questions; silences” (56).

Figure 4: Rosine Mbakam appears in the fragmented frame too. At Jolie Coiffure. Screenshot.

Dwelling as Decolonial Framing

In a political economy where the work of domesticity still falls onto women, how can we translate their lived experience of home in visual terms? I have shown how the films complicate national narrations of intimacy and attachments, illustrating the multifaceted definition of home for migrant women in Europe. I demonstrated how the process of filmmaking opens a space for the protagonists themselves to perform decolonial gestures. Delphine and Sabine’s respective homes are places of precarious intimacies, simultaneously offering desired closeness, violent intimacies, as well as the potential to articulate decolonial practices. Their ability to remain in the domestic space of Belgium is contingent on bureaucracy (for Sabine) and a postcolonial sexual economy (Delphine). In this respect, the films construct temporality as indissociable from home. I suggest looking at the home as dwelling—a location, a temporality and an affect. Dwelling is made of elongation, fixity, repetition, and fragmentation; but it also asks us to look at the role of the body and emotions in inhabiting space. As Giuliana Bruno points out: “After all, habitus, as a mode of being, is rooted in habitare, dwelling. That is to say, we inhabit space tactilely by way of habit, and tangibly so” (32). I argue that Mbakam’s attention to interior architecture creates a filmic structure, working within the medium itself to compose shots that challenge representations of diasporic homes. Mbakam represents the domestic, which is shaped by how “it is practised in everyday life” as well as the larger infrastructural and “social constructions” (Baschiera and De Rosa 4). The domestic is also a space where hegemonic narratives can be challenged in the very fabric of their visuality.

The experience of temporality is a crucial aspect in the creation of diasporic homes. The new home is composite, constituted in the present by the futurity of its own potential, and the past carried by the memory of the home that was left—reimagined or romanticised (Ahmed, Uprootings 10). For example, when asked if she feels at home in Belgium, Sabine replies: “Belgium is my village”, while at other times she longs for a “return home” to visit Cameroon. Made of “archaeological layers”, diasporic homes are a constant dwelling in progress, places of nostalgia for the home that was left, together with the new pleasures found, thus complicating linear temporalities of “leaving home” and “being-at-home” (Boym 500, 502; Ahmed, Strange Encounters 77). Home is constituted through habits, quotidian practices, infinitesimal gestures, and repetitions. Mbakam’s feminist practice captures the passing of time, made of waits, repetitions, and circularities in the home. The films carry a life-like aspect while the fixity of the shots elongates duration. The shots are rather static as the women on screen either move within the frame, dwell, or look inward. Mbakam is concerned with the seemingly uneventful, sticking to the daily experience of Sabine and Delphine to portray their subjective apprehension of time. We see Sabine’s phone screen as she silently watches a show. Delphine makes her bed for the duration of a whole sequence. No marker indicates how many days or months Mbakam sits with the women, and we could only guess the passing of time from sartorial choices. Her project is reminiscent of Chantal Akerman’s work, whose film Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) challenges representations of women for scopophilic pleasure, instead focusing on the repetition of quotidian gestures usually unrepresented in movies because they are associated with women’s labour in the domestic space (Treilhou 92).

At Jolie Coiffure is composed of temporal episodic fragments and recurrences which serve to translate quotidian repetition. Customers leave and come back over the days, Sabine waits for her patrons, fixes her hair, combs weaves, or simply daydreams. A friend and fellow business owner keeps dropping by the shop, his incursions like a leitmotiv underscoring the film’s pace. Sabine even tells her story of migration twice: first in the third person and later using “I”. In comparison, Delphine’s Prayers is even more reliant on banal repetitions in the home space. Providing a frame for Delphine’s storytelling, each chapter of her narration is preceded by a sequence of Delphine doing her hair and makeup for the day’s shoot while conversing with Rosine. As Delphine recounts the past together with her current situation, she manifests her conflictual relationship to home. She is well aware of the precarious intimacies that both limit her freedom and foster desired closeness with some individuals, thus generating a space to articulate critiques and craft oppositional practices in the everyday.

The affective dimension of the home is also deployed in the body, materiality, and objects (Ahmed, Uprootings 9). In the films, dwelling takes the form of long takes that linger on the protagonists’ faces in medium and close-up shots to convey not only their messages to the audience but also the depth of their experience. In Delphine’s Prayers, Mbakam’s camera gets closer to Delphine than it gets to Sabine in At Jolie Coiffure, showing her friend’s face in close-up shots from a variety of angles. At the end of the film, Delphine strikingly sits in silence in front of the camera, and the audience is left to explore her facial and bodily expressions. The shot is long and static. We cannot look away as we attempt to grasp the ineffable nature of Delphine’s experience.

Figure 5 (above): Rosine prepares Delphine for a silent take. Figure 6 (below): Delphine and her objects.

Delphine’s Prayers (Les Prières de Delphine). Directed by Rosine Mbakam.

Tândor Productions, 2021. Screenshots.

Delphine’s interiority seems to infuse objects around her, expanding dwelling. As the film progresses, her face becomes increasingly framed among objects, all in the foreground, like still-life compositions. Sometimes, Delphine is framed on one side and objects on the other, like a screen split in two. A collection of various lamps, empty cans, folded blankets, dominoes, and photo albums are scattered on the table in front of her bed, where she lies as she talks. Objects help register the passing of time as Mbakam comes back several days in a row to interview Delphine, mirroring the accumulation of stories collected. All are indications of Delphine’s quotidian and banal activities in her home. They tell stories of Delphine’s life at home, silently complementing storytelling of the broader strokes of her trajectory. These shots encapsulate Delphine’s complex situation: on the one hand, the stillness and profusion of objects signify a part of Delphine’s stasis, caught in an oppressive marriage and facing paralysing institutional racism. On the other, the temporality of objects and their constant shuffling also mirror the acts of resistance of a woman who acts for change.

The exploration of Delphine’s interior dwelling extends to the architecture of the home itself as Mbakam’s camera studies the interior architectural space as one of memory and overlapping temporalities (Rascaroli 137). Shots of objects without Delphine in the frame adopt unconventional, sometimes disorienting angles to convey impressions, like “interiors as out-of-focus spaces” (Bruno 176). Mbakam’s aesthetic of angles and fragmentation is a visual way to inscribe temporal and subjective depth in the fabric of the film. The screen itself is divided by lines and segments, like vignettes, which in turn create multiple layers of temporal inhabitation on screen. Moreover, she creates frames-within-frames and hypergeometric structures to reflect the women’s fragmented experience and their complex dwellings. This hyperframing produces composite images that overlay several temporalities and actions within the shots, showcasing the mutability of dwelling. Several silent shots show a particular angle of Delphine’s room: the junction of two walls, a square angle which Mbakam frames in the centre. On the right wall, two pictures represent who might be Delphine’s family. Another shot is split diagonally by the geometry of the room: on the left-hand side, we see the inside of the bedroom; on the right-hand side, the outdoor area is visible through the glass door window. On the one hand, the coexistence in the shot of both inside and outside reinforces the porosity of the home, never quite immune from the outside world and structured by external factors. On the other, it highlights Delphine’s multitemporal dwelling and how she navigates her identity, at the crossroads, in her personal space.

Figure 7: Architectural geometry. Delphine’s Prayers. Screenshot.

In At Jolie Coiffure, geometry takes on a new level as Mbakam plays with mirrors, essential features of hair salons, to compose her shots. In static shots, Mbakam sometimes frames Sabine in mirrors, her face split by this frame within the frame. This ontological cut, like a window within the screen leaves the audience to make sense of the composition, understanding the larger ramifications of Sabine’s home experience and their own role to play (Friedberg 155). Sabine is showcased in her multiplicity as several mirrors reflect each other.She is often shown with other workers, patrons, and friends, all occupying different vignettes on screen, but several shots also display the constant flow of white intruders in the background while Sabine goes about her activities. Such complex mirror shots, which break the illusion of seamless composition and editing, make the spectator aware of the act of viewing (Hanich 182). As this mirror play reflects multiple temporalities and experiences simultaneously on screen, it also reflects to the spectators—in their life, are they complicit with the white colonial gaze or are they a part of Sabine’s extended community?

Figure 8: Angular dwelling. Delphine’s Prayers. Screenshot.

Eventually, Mbakam’s framing shows how dwelling is conditioned by enduring colonial ideologies of race and nationalism. The end of Delphine’s monologue in Delphine’s Prayers further serves as an illustration. In the first part of the sequence, Delphine expresses regrets about her move to Belgium and shares her thoughts on the complicated discourses of returns to the homeland. She warns against the idealisation of Europe and wants her story to be a dissuasive example for people in Cameroon contemplating a similar move. Originally promised the “White’s paradise”, all she found in Belgium was a sense of loss and hostility. As she speaks, her body is off the screen, her testimony in voiceover. The visual on screen is a static shot of the beams supporting the glass roof, displaying a clear blue sky, in contrast to the sentiment expressed by Delphine. In the next sequence, Delphine holds a piece of white paper so Rosine can set the white balance for her camera. Delphine jokes about race—“so much suffering for white balance.” Delphine’s playfulness on whiteness as a visual category and the omnipresence of the colour white further criticises arbitrary constructions of race and white hegemony, all the while showing how such discourse has pervaded our understanding of visuality and technology. Delphine bends over and momentarily exits the frame, but Mabkam keeps the camera focused on the white caster wall in front of which Delphine sat during the film. We already saw this wall before, when Delphine had to leave the room to tend to her child. In the absence of moving visuals and the human referent, the audience now focuses on Delphine’s words but also on the texture of the white wall. The importance of Delphine’s message exceeds her physicality.

Framing abstraction and texture in these lengthy shots is a call for the audience to turn inward and self-reflect on their own dwelling alongside Delphine. As full participants, we see the domestic space “as an architecture, that is, a place to be practised, inhabited, built by a spectator who will feel and acknowledge her/his empowerment towards spatiality” (Baschiera and De Rosa 17). At the same time, we must think about where we stand in terms of our participation in colonial duress and homing. Is the viewer complicit in the colonial project or practicing decoloniality?

Home Beyond the Frame

I have shown how Mbakam’s decolonial cinema intervenes during the filmmaking process to undo the separation between the documentarian and the subjects of documentary and record the intimate lives of immigrant Black women and their diasporic attachments. Filming the women in their private homes (Delphine) and the intimate space of the salon (Sabine) extends to commenting on how the home is also a public construction, enmeshed in discourses on the domestic and the national. Mbakam’s commitment to decolonial cinema interrogates politics of representations and is encoded in the images themselves. In the composition of her shots, Mbakam testifies of complex diasporic dwellings and makes space for the spectators to reflect alongside Sabine and Delphine. Throughout At Jolie Coiffure and Delphine’s Prayers, Mbakam manifests the lack of infrastructure available to Black women filmmakers and Black women migrants in the image itself. “My cinema is not diplomatic, it is confrontational.” That is what Rosine Mbakam said to me when I interviewed her and Delphine. I learned more about their bond, the genesis for the project and their commitment to social change for African women. In our conversation, Mbakam made it clear that she conceives of her documentaries not just as films but as documentary events. To fully grasp her commitment to decolonial cinema requires shifting our attention from the screen to include audience reception and infrastructures.

Lindiwe Dovey wrote that audiences go to a film screening not only for the film itself but as an activity and an experience, a social event thus showcasing the “porous boundaries between production and reception in many African contexts” (14–15). Historically, the cinematograph was introduced on the African continent from its early start and was quickly turned into a tool for colonial propaganda, especially through mobile screenings which took colonial films and selected European films across countries and villages to “educate” (Ukadike 218; Dovey 17). This tradition of mobile cinema has since been reclaimed by Africans. In Cameroon, for example, the Cinéma Numérique Ambulant has been especially active in taking African films to local populations across the country. Such mobile screenings are infrastructures which redress the lack of existing avenues and visibility for African cinema. With the production company she started, Tandôr Productions, Mbakam launched her own mobile cinema program called Caravan Cinema, a “mobile infrastructure” which takes her films back to Cameroon where they are shown in community events (Price, “Unfinished Stories”). For Mbakam, this opens conversations that decentre European films, which saturate the market, focusing instead on local and transnational African experiences “so that thanks to the cinematic screen, people can have enough distance to question their reality” and “decolonise their thinking” (Interview). In these screenings, the topic of migration helps to reach out to young people who consider taking the same route as Sabine and make them reconsider, especially as it connects to modern enslavement and sexual exploitation.

For Mbakam, then, people in Cameroon must confront the realities of the myth of Europe as a welcoming home and recognise the colonial discourse that has asserted European hegemony in the collective imagination and create new futures. This is why she envisions her work beyond the borders of Cameroon, for all Africans and especially those who suffered the cruelties of migration. For example, in our interview, Mbakam discussed Delphine’s activities with associations supporting Nigerian sex workers who have been trafficked. When we spoke, Delphine’s Prayers was going to be projected in special screenings to inspire these sex workers to talk and work through their own experiences.

Mbakam’s decolonial practice creates connection and collective attachments. It calls to mind Lauren Berlant’s distinction between structure “as that which organizes transformation”—in this case, Mbakam’s films—and infrastructure “as that which binds us to the world in movement and keeps the world practically bound to itself.” If infrastructure is “the living mediation of what organizes life”, Mbakam’s audience practices shape new socialities and infrastructural intimacies (393). Her films provide structure for change and Caravan Cinema produces the flow and bonds to shape a new sense of home in Cameroon, Africa, and France. Her films extend beyond a representation of the private home as a site of resistance on screen to house pluriform experiences of home which the spectators are invited to dwell in for a limited duration. That includes the making (which is still visible in the film), the screening, and the discussion. In Mbakam’s own words: “With At Jolie Coiffure, people did not need to go to the salon. Through the screen, they could see reality.” Mbakam’s documentary practice is “concerned with creating hospitable spaces, with allowing enough trust to see where an invitation leads (trust as opposed to truth), and with providing a starting point for shared ground” making room to connect “on-screen aesthetic concerns and off-screen social arrangements” (Fox).

But how does one effectively produce social change through film? Delphine’s Prayers and At Jolie Coiffure resist resolutions, and “returned-home-safely closure [which] closes off the possibility of change, which must occur outside the film” (Godmilow 18). Instead, Mbakam creates a direct injunction for the audience members to react to what they have seen and think with the women on screen. As previously discussed, Mbakam creates filmic strategies that maximise audience engagement instead of passive viewership. Importantly, whenever Sabine and Delphine share their migratory journey, they face the camera in medium and close-up shots, looking at Mbakam who is located right behind the lens and, by association, us. For the audience, then, there is no looking away, we are members in attendance of this discussion.

At Jolie Coiffure ends the way it begins, with Sabine braiding hair. Her patron asks her if she is going back to Cameroon soon, to which Sabine replies that she does not know. The screen cuts to black and the credits roll out. The documentary is a slice of life and offers no resolution to Sabine’s pleas, simply laying out the realities of her experience. Sabine’s last words, “I don’t know…”, leave a pathway for dialogue around migration and diaspora to continue in the audience. It is a bit different in Delphine’s Prayers, whose ending is composed of two performances which, if they effectively close the film, do not offer a “returned-home-safety closure”. First, Delphine performs a prayer. Then she braids Rosine’s hair, both facing us as the latter reads a letter in voiceover describing how their friendship has been shaped by the history of colonialism that has produced the modern Black diaspora. In some respect, this final sequence might reaffirm Mbakam in her role as filmmaker, conferring her the power to conclude the documentary—a tonal change from the rest of the film. But it is also a gesture of provocation: the admission of her privilege in Cameroonian society calls for an interrogation of structural inequalities that starts in the country. Rosine’s voice and bodily stance constitute a direct address to enter the conversation. In the very first sequence, we were invited into Delphine’s home. Now, we are invited to stay and talk at the documentary event.

Figure 9: Rosine and Delphine face the audience in a final reversal of the gaze. Delphine’s Prayers. Screenshot.

The final and indispensable confrontation underlying Mbakam’s decolonial cinema is directed toward a white audience. In Belgium, Sabine has often attended the screenings, which largely attract white audiences. Her presence in the theatre is crucial in precluding “fraudulent intimacies” which naturalise white distance and reward the spectator for their benevolence (Godmilow 16). The filmic reversal of the colonial gaze in the film, as I have discussed earlier, extends to a confrontation during the Q&As, thus challenging “the momentary satisfaction of concerned citizenship” afforded to traditional white middle class audiences (Godmilow 16).

In fact, At Jolie Coiffure displays evident episodes of white supremacy and institutional, racist violence. Cernaix’s montage creates evocative images of white people’s complicity in white coloniality. In a terrifying sequence I mentioned earlier, the whole mall is threatened by a police raid. Sabine, undocumented, must react quickly and rushes out of the salon. She switches off the light and closes the door, but Rosine remains inside with her camera. Sabine calls Rosine on her cell phone to ensure that the salon looks closed. Meanwhile, Rosine’s camera captures the officers walking past the salon, looking for people to arrest. The sequence cuts to another one displaying the white tourist and racist gaze. These people are visibly entertained while Sabine is working in the foreground. The African neighbourhood of the Matongé is under the threat of a state that imagines its domestic space as white, a location in the process of being gentrified, but also an attraction for the white colonial gaze. In this sense, we are reminded of the power of visuality to create categories of exclusion. As Gayatri Gopinath puts it: “Imperial, settler colonial, and racial regimes of power work through spatial practices that order bodies and landscapes in precise ways; these regimes of power also instantiate regimes of vision that determine what we seem and how we are seen” (7). The white tourists look inside the salon, and they face us now, the audience who has been sitting with Sabine and her friends throughout the film. By pointing the camera back to the white gaze, Mbakam reflects it back at the white audience members, now experiencing the gaze too.

Figure 10: Sabine challenges the white colonial gaze. At Jolie Coiffure. Screenshot.

During our interview, Mbakam described adversarial and violent reactions from white audience members, provoked by this reversal of the gaze. She spoke of one man who demanded her to apologise for her film, and others accusing her documentaries of being racist against white folks. The confrontation has worked, proving that cinema does not just capture reality, it is not a “second-order mirror held up to reflect what already exists, but [a] form of representation which is able to constitute us as new kinds of subjects, and thereby enable us to discover places from which to speak” (Hall 236). Mbakam’s cinema reminds us that decolonising the home calls for new imaginations and a reframing of the regime of vision in the medium itself to shape new dwellings.

Note[1] A tontine is an informal savings and credit system, in parallel of the banking system. A group of people decides to get together to pool a part of their money under rules set by the group. They each regularly pay their members’ dues. The group then decides to finance specific projects from member(s) and/or to support some of them through personal situations. The tontine also helps strengthen social bond and community-based solidarity. In the case of women in Cameroon, tontines contribute to asserting material independence from their husbands.

References

1. Ahmed, Sara. Strange Encounters: Embodied Others in Post-Coloniality. Routledge, 2000. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203349700.

2. ——, editor. Uprootings/Regroundings: Questions of Home and Migration. Berg, 2003. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781474215909.

3. Akerman, Chantal. Jeanne Dielman. 23 Quai Du Commerce 1080 Bruxelles. Paradise Films, 1975.

4. Andrade, Susan Z., The Nation Writ Small: African Fictions and Feminisms, 1958–1988. Duke UP, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822393740.

5. Baschiera, Stefano, and Miriam De Rosa, editors. Film and Domestic Space: Architectures, Representations, Dispositif. Edinburgh UP, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474428941.

6. Berlant, Lauren. “The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times.” Environment and Planning D: Society & Space, vol. 34, no. 3, 2016, pp. 393–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775816645989.

7. Boym, Svetlana. “On Diasporic Intimacy: Ilya Kabakov’s Installations and Immigrant Homes.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 24, no. 2, Winter 1998, pp. 498–524. https://doi.org/10.1086/448882.

8. Bruno, Giuliana. Public Intimacy: Architecture and the Visual Arts. MIT P, 2007.

9. Dovey, Lindiwe. “African Film Festivals in Africa: Curating ‘African Audiences’ for ‘African Films’.” Black Camera: The Newsletter of the Black Film Center/Archives, vol. 12, no. 1, 2020, pp. 13–47. https://doi.org/10.2979/blackcamera.12.1.03.

10. Ellerson, Beti. “African Women in Cinema Dossier: African Women of the Screen as Cultural Producers: An Overview by Country.” Black Camera: The Newsletter of the Black Film Center/Archives, vol. 10, no. 1, 2018, pp. 245–87. https://doi.org/10.2979/blackcamera.10.1.17.

11. Fox, Jason. “Can Documentary Make Space?” Film Quarterly Quorum, 4 Jan. 2020, filmquarterly.org/2020/01/04/can-documentary-make-space.

12. Friedberg, Anne. The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. MIT P, 2009.

13. Ginsburg, Faye. “Decolonizing Documentary On-Screen and Off: Sensory Ethnography and the Aesthetics of Accountability.” Film Quarterly, vol. 72, no. 1, Oct. 2018, pp. 39–49, https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2018.72.1.39.

14. Godmilow, Jill. Kill the Documentary, Columbia U P, 2022. https://doi.org/10.7312/godm20276.

15. Gopinath, Gayatri. Unruly Visions: The Aesthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora. Duke U P, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478002161.

Hall, Stuart. “Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” Identity, Community, Culture, Difference, Lawrence and Wishart, 1990, pp. 222–37.

17. Hanich, Julian. “Reflecting on Reflections: Cinema’s Complex Mirror Shots.” Indefinite Visions: Cinema and the Attractions of Uncertainty, edited by Martine Beugnet et al., Edinburgh UP, 2018, pp. 287–332. https://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9781474407120.003.0009.

18. Larkin, Brian. Signal and Noise. Duke UP, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822389316.

19. ——. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 42, no. 1, 2013, pp. 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155522.

20. Mbakam, Rosine, director. At Jolie Coiffure [Chez Jolie Coiffure]. Tândor Productions, 2018.

21. ——, director, Delphine’s Prayers [Les Prières de Delphine]. Tândor Productions, 2021.

22. ——. Interview. Conducted by Julie Le Hegarat. 7 Mar. 2021.

23. Mbakam, Rosine, An van Diederen, and Eléonor Yameogo, directors. Prism [Prisme]. Tândor Productions, 2021.

24. Obolo, Pascale. La Fabrique des contre-récits. Centre Audiovisuel Simone de Beauvoir, 2021. DVD.25. Price, Yasmina. “On Prisms and Portraits: The Films of Rosine Mbakam.” Screenslate, 8 Oct. 2021, www.screenslate.com/articles/prisms-and-portraits-films-rosine-mbakam.

26. ——. “Unfinished Stories: A Conversation with Rosine Mbakam.” Criterion.com, 28 Mar. 2022, www.criterion.com/current/posts/7735-unfinished-stories-a-conversation-with-rosine-mbakam.

27. Rascaroli, Laura. “No Home Movie: Essay Film, Architecture as Framing and the Non-House.” Film and Domestic Space, edited by Stefano Baschiera and Miriam De Rosa, Edinburgh UP, 2020, pp. 276–301. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474428941-014.

28. Sita-Bella, Thérèse, director. Tam Tam à Paris. Ministry of Culture Cameroon, Yaounde, Cameroon, 1963.

29. Stehle, Maria, and Beverly M. Weber, editors. Precarious Intimacies: The Politics of Touch in Contemporary Western European Cinema, Northwestern UP, 2020. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv14161gx.

30. Stoler, Ann Laura. Duress: Imperial Durabilities in Our Times, Duke UP, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv125jn2s.

31. ——, editor. Interior Frontiers: Essays on the Entrails of Inequality, Oxford UP, 2022. https://doi/10.1093/oso/9780190076375.001.0001.

32. Tchouaffé, Olivier J. “Women in Film in Cameroon: Thérèse Sita-Bella, Florence Ayisi, Oswalde Lewat and Josephine Ndagnou.” Journal of African Cinemas, vol. 4, no. 2, 2012, pp. 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1386/jac.4.2.191_1.

33. Treilhou, Marie-Claude. “La Vie, il faut la mettre en scène...” Cinéma 76, vol. 206, Feb. 1976, pp. 89–93.

34. Trinh, T. Minh-Ha. When the Moon Waxes Red: Representation, Gender, and Cultural Politics. Routledge, 1991.

35. Ukadike, N. Frank. “Africa.” The Documentary Film Book, edited by Brian Winston, Palgrave Macmillan/BFI, 2013, pp. 217–27.

Suggested Citation

Le Hegarat, Julie. “‘My Cinema Is Not Diplomatic, It Is Confrontational’: Decolonial Framing of the Home in Two Documentaries by Rosine Mbakam.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 26, 2023, pp. 6–24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.26.01

Julie Le Hegarat is a researcher, educator, and video essayist located in Vancouver. She is currently teaching at the School for the Contemporary Arts at Simon Fraser University. Her forthcoming publications include an article for the Journal of Cinema and Media Studies on critical pedagogy in hostile climates. She is working on her first book project manuscript, Violent Ingestions, which looks at antiassimilationist and decolonial gestures in film and media from the Global Atlantic. She obtained her PhD from Indiana University, Bloomington in 2022.