Europe of “Others”: Deviations, Mobility, and the Construction of Identities in Carmine Amoroso’s Cover Boy

Abigail Keating

Introduction

Cover Boy (2006) is the second feature film by Italian director and screenwriter Carmine Amoroso, following his debut feature As You Want Me (Come mi vuoi) in 1997. It is set in the period before the 2004 expansion of the European Union and follows the journey of Ioan (Eduard Gabia), a young Romanian man, from his home in Bucharest to Rome, having been persuaded by his friend Bogdan (Rolando Matsangos) that they would make a better living in Italy. Unlike typical portrayals of the migrant’s longing for a more prosperous existence in another, wealthier country, Ioan seems reluctant to leave Romania at first, but eventually accepts at Bogdan’s insistence. They travel by train on short-term visas, but when the immigration police check their documents there is an issue with Bogdan’s papers and he is inevitably detained. Ioan is therefore left to fend for himself without his companion and the many connections and opportunities that he had promised to him. After spending a few nights sleeping rough and walking the streets of Rome in the naïve hope that he will be reunited with Bogdan, Ioan meets Michele (Luca Lionello), an Italian janitor working in Termini train station. While Michele’s attitude towards him is initially hostile, the two men soon come to an arrangement whereby Ioan will pay to share Michele’s accommodation. The friendship between the men grows deeper before we come to realise that Michele is harbouring feelings for Ioan. Although there is little physical intimacy between the two, there is an undeniably romantic atmosphere throughout the film.

The notion of an exclusive “European” identity is thematically present throughout Cover Boy: firstly, via its East/West encounters and the highlighting of the Romanian migrant as a marginalised figure in the West; and secondly, as it begins and concludes with geographical (and personal) journeys made by Ioan over the border from Eastern Europe to Western Europe in the hope of prosperity, and back again, after becoming aware of the few (demeaning) options that are available to him as an “outsider” looking for work, as well as the hostility that he faces there. Through this, the idea of an intra-European binary arises. However, the notion of the beleaguered Eastern European migrant and the privileged Westerner, in the form of Michele, is ultimately quashed via Amoroso’s intertwining of the two men’s “otherness”, through unstable employment but also through more intimate aspects of their identities—most significantly, as I shall discuss in depth, their detachment from/ultimate rejection of heteronormative (and thus Italian) society and the unspoken “queerness” of their relationship. In their reading of the film from the perspective of transnational mobility and precarious labour, Alice Bardan and Áine O’Healy have pointed out that these two figures represent “a survivor of the collapse of communist ideology and a victim of the ruthless logic of globalized capitalism” (2), and that, by juxtaposing their respective “otherness”, Cover Boy:

diverges from almost all other Italian films featuring immigrant characters by showing that despite the strong undertone of xenophobia and racism directed at migrants, Italians share with immigrants a level of economic precariousness and a strong desire to secure a better life. (6)

Aesthetically, the narrative is accompanied by the recurrent use of reconfigured images, sounds, themes and ideologies. I use “reconfiguration” as a broad concept here, encompassing, firstly, the manipulation of already existing material through remixing, secondly, the act of mirroring shots and scenes with previous events in the film, which help to configure meaning in the latter, and lastly, Amoroso’s technique of allusion and creating connections between seemingly unrelated events. To be more specific, reconfigurations occur throughout the film in the literal sense through Amoroso’s inclusion of remixed images and sounds in the diegesis, which are significant to the narrative and prove at times to be unethical and deeply problematic, and in the more interpretative sense through Amoroso’s tendency to (re)present scenes that recall—and thus instigate an ideological or thematic juxtaposition with—another scene/event in the film. Given the film’s two main locations, Bucharest and Rome, and the likening of events and moments in the film, as well as elements of the mise en scène, this technique is crucial to a reading of Cover Boy’s sociopolitical leanings, in that a cross-national dialogue on the topic of “otherness”, and thus Amoroso’s deviation from representational conventions, as Bardan and O’Healy have noted, are firmly established and maintained as the narrative unfolds. This is an area that informs much of the general focus of this article, but I also aim to expose Amoroso’s more subtle orchestration of the tropes of inclusion and marginalisation, via his use of Western/Italian space and the individual and collective identities that are upheld, and ultimately undermined, in its urban environs.

Specifically, I argue that it is through the director’s use of deviation and mobility within the film’s principal setting of Rome and, in an overt way, cross-nationally that more intricate questions of the constructedness of Western (and privileged) European identity are able to emerge. Much of my textual analysis is devoted to unearthing Amoroso’s use of mise en scène as a way to, paradoxically, highlight and eventually challenge the notion of an East/West binary. The theme of mobility is particularly significant in this regard, in that it is through the characters’ movements through the streets of Rome that their statuses as “other” are established. Along the way, the problematics of identity are also revealed through Amoroso’s narrative interest in performance, both conventionally (through acting, music, modelling and photography) and, more implicitly, as many of the characters in Cover Boy present themselves falsely, in varying comic and complex ways. As I shall examine, this (re)configuration of identities can then be read in the broader context of Amoroso’s aesthetic of (re)presentation—where the themes of performance and individual and collective identity are strikingly evoked in the latter half of the film, in particular.

It must also be noted here that Cover Boy, in particular its setting, was significantly impacted by production constraints. Amoroso’s budget was originally two million euros, having been approved for funding by the Italian Ministry of Arts. But, as a result of policy changes implemented by Silvio Berlusconi’s coalition government in 2004, the film’s budget was slashed by seventy-five per cent. Consequently, Amoroso had to make significant changes to the screenplay and production; most notably, he had originally wanted to set a large portion of the film in Bucharest in 1989—where the film’s story begins—but was inevitably unable to do so (Bardan and O’Healy 2). As I shall discuss, however, Amoroso has the last word on the Berlusconi coalition’s notoriously right-wing practices, as he places the attitudes and impact of this government in ideological proximity to the socioeconomic failings and sociopolitical tensions of Eastern Europe pre–1989. This juxtaposition occurs between the film’s opening and penultimate sequences, the latter serving as a climax to Cover Boy’s often subtle but continual trope of identity construction and its links with social inclusion.

Finally, with this, I explore the film’s themes of individual and collective identity through the commentary of Zygmunt Bauman. While I engage with the film’s focus on precarity in this article, I do so in a bid to examine Cover Boy in the context of identity construction and beyond the topic of labour and its representational tropes, as Bardan and O’Healy have already convincingly done. Here, I expose the film’s sociopolitical and socioeconomic interest in “otherness” through Bauman’s essay “Europe of Strangers”, specifically, proposing it as a further way of reading the film within a contemporary European paradigm—to which, I argue, the issues raised at the end of Cover Boy adhere both explicitly and implicitly. Again, the notion of a solid identity is undermined through Amoroso’s underlining of the pretence involved in upholding a contemporary, Western, capitalist society.

Deviations: Europe, Mobility and the City of Rome

Cover Boy is classed as a fiction film, but one of its most memorable sequences is a montage of archival footage of historical events in Europe (and related events elsewhere) documenting the Cold War, the revolts on the streets and the Fall of Communism in 1989, which occurs at the very beginning of the film. The montage is accompanied by a light, melancholic piano soundtrack—setting the tone for the music throughout the film—until US President John F. Kennedy’s famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” statement during his declaration of support for West Germany in 1963 interjects. Seconds later, US President Ronald Reagan’s speech at the Brandenburg Gate near the Berlin Wall in 1987 is shown, during which he urges “Mr. Gorbachev, open this gate!”, in an appeal to the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev, to tear the Wall down for the cause of freedom and peace between East and West. Other key historical moments that are shown include the violent clashes in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests in Beijing, some brief footage of civilians with hammers (“Mauerspechte”) hacking at the Berlin Wall and indeed the subsequent demolition of the Wall, along with a number of scenes of violence, street protests and military marches. The montage ends with footage of Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu’s last speech in December 1989 (before his execution) during the Romanian Revolution, followed by more scenes of street violence and civilian casualties. Prior to these final scenes, Amoroso includes an animated map of Eastern and Central Europe, where the camera zooms in on Romania, followed by a shot of the Romanian border (where a “Romania” sign is evident) as taken from a moving vehicle. These are the only clear pieces of written information included in the montage, insofar as there are no intertitles giving dates or geographical locations; instead, the director relies on the viewer’s own familiarity with these momentous events of sociopolitical upheaval. Moreover, this information locates the beginning of the film in Romania in 1989 where what ensues is a sequence depicting a significant moment in a young Ioan’s life.

In this sequence, the country’s tumultuous events unfolding on a television set direct our attention to the conflict, as a young Ioan (around eight or nine years of age) watches, worriedly awaiting his father’s return home. When he does return, he proceeds to take Ioan out of the city, away from the conflict on the streets, at which time they encounter an injured woman lying on the road. Ioan’s father, a doctor, gets out of the car to help the woman, but as he walks towards her two loud shots ring out and he falls down dead. An image of the young Ioan in his father’s car fades to a present-day image of a similar car from which Ioan emerges as an adult. He now works as a mechanic in his hometown of Bucharest, and here he encounters his friend Bogdan who, as noted, convinces him to migrate to Rome with him.

Upon his arrival in Rome, Ioan’s lack of familiarity with the city is foregrounded by a montage of scenes that commences as he is seen arriving at a packed Termini station. Here, an extreme long shot pulls away and reveals his dwarfed figure at the centre of a busy urban scene while large Armani billboards loom at the top of the frame. When he leaves the station, the camera encircles him in a number of arc shots while the loud pounding of bongo drums fills the soundscape; a fluid shot of the Colosseum is then juxtaposed with Ioan’s tiny figure gazing at it in wonderment. This music then becomes diegetic as we see Ioan sitting down next to a group of street musicians playing drums. With this, the ethnic diversity of Rome’s streets and the informal economy in which many migrants are forced to partake are immediately evoked. Interestingly, one shot of Ioan watching the musicians play is presented in slow motion—the fluidity of the drummers’ out-of-focus hands contrasting with Ioan’s unmoving, in-focus figure in the background of the frame, signalling the various themes of mobility and fixity with which the film is about to engage.

Ioan then returns to the Colosseum, not as a tourist and not with a sense of wonderment this time, but rather as someone who seeks a safe place to spend the night. Indeed, this is the case until a Roman gladiator (a familiar sight for anyone who has visited Rome as a tourist), intimidatingly shot from a low angle, claims territory over the patch on which a sleeping Ioan lies, threatening him with a (presumably) fake sword and ultimately ejecting him from the space. We then see Ioan washing himself in one of the many fountains in Rome in an attempt to maintain a decent appearance, having been warned by Bogdan earlier that he should avoid looking like an unkempt Romanian migrant. Here, there is an emphasis on Ioan’s basic, personal use of Rome’s features—as elements of survival for sleeping, personal hygiene and safety. A sense of temporariness subtly accompanies these scenes also as, along the way, the camera fixes itself on a number of hotel signs and devotes significant attention to the high level of homelessness on the streets. Furthermore, Amoroso displays particular sensitivity to the ethnic diversity of the city’s homeless residents; through this and the underlining of Ioan’s hopeless situation, the idea of hostility towards the migrant “other” is implicitly established. Therefore, the initial emblem of wealth that is presented at the beginning of this sequence—in the form of the Armani billboards and their allusions to glamour—is superseded by the version of the city of which Ioan is now a part, in accordance with Derek Duncan’s observation of how media “images of Italy as a wealthy, consumerist paradise conflict with the brutal realities of poverty, exclusion and violence that characterize the migrant’s actual experience” (173).

Indeed, this hostility is more explicitly dealt with upon Ioan’s first encounter with Michele, to whom we have already been introduced as a janitor at the station during a brief scene of him going about his work. Once again, Ioan is ejected from the space and told to never return. During their second encounter, however, Michele’s attitude towards the young migrant softens and they devise a living arrangement. Interestingly, it is after this that a key scene occurs in relation to Amoroso’s emphasis on inclusion and marginalisation via the characters’ access to mobility within their urban surroundings. Until this point, Ioan’s navigation of the city has been restricted, firstly, in that he is continually told by figures who claim authority that he has to leave a particular (for the most part, public) space: the Roman gladiator, the police during one brief scene and, at first, Michele in his janitor’s uniform. Ioan’s access to mobility is also undermined more subtly through the sight of his pitiful wandering continually juxtaposed with the fluidity of passing vehicles, and indeed with the focus on transport in general in the first few Rome sequences, in that many scenes take place in and around a train station. However, now that he has befriended an Italian native he is finally able to go somewhere—to Michele’s apartment on the back of his Vespa. Aside from this, when Ioan eventually finds work, it is as a mechanic on the outskirts of the city, where the sight of old, broken-down vehicles piled on top of one another serves as a significant backdrop: we later learn that Ioan is not the only undocumented migrant employed here, thus the linkage between vehicular mobility and the migrant’s lack of ability to partake in free mobility is strikingly evoked.

Figure 1: Michele accompanies Ioan around the city in Cover Boy (Carmine Amoroso, 2006). Paco Cinematografica, 2006. Screenshot.

More significantly in the context of the Italian native, however, the link between mobility and inclusion is established in a later scene of the men travelling around the city on Michele’s Vespa. By now, they have begun to form a deep friendship and, through a few subtle point-of-view shots in which Michele’s gaze is fixed on Ioan’s face or body, the idea that his feelings towards Ioan are romantic has been subtly evoked. In this short montage of the men driving around the city, Ioan is again accompanied, and piano music of a similar tone to the film’s opening sequence suffuses the Vespa scenes with a warm yet melancholic atmosphere. However, during this sequence, Michele’s Vespa begins to have engine trouble and eventually breaks down. From this juncture, where Michele’s power over his ability to move fluidly through Rome is problematised, I would argue that the two men’s situations and “otherness” become interwoven instead of being presented in contrast to each other—as an Italian native and an undocumented, non-EU migrant, respectively. They get the Vespa restarted and make their way to the sea in Ostia, where Amoroso uses this location and its seclusion to underline the intimacy between the men and their parallel situations, as well as to highlight the idea that, in the eyes of many, both of these men are “others”.

They settle down for the night, build a fire and have a deep discussion about spiritual faith. The next morning, the beach is still secluded and the men run into the sea in what is perhaps the happiest scene in the film. They euphorically jump and splash around, enjoying the sense of freedom of their being alone and their nakedness, before a particularly tender moment occurs between them. When Ioan informs Michele that he cannot swim, the latter cradles him in his arms lovingly, before playfully dropping him underwater, where he then follows him.

Figure 2: An intimate moment between Michele and Ioan in Cover Boy. Paco Cinematografica, 2006. Screenshot.

Extreme close-ups of the men’s bodies and the blurriness of the sea create an intense atmosphere in which there appears to be a mutual sense of affection. [1] In a subsequent scene, when Ioan asks him if he has a girlfriend, Michele’s closeted sexuality is perhaps confirmed, as he somewhat nervously repeats the excuse that he prefers to be free rather than being tied down to a woman. Indeed, the idea that Michele feels restricted in his situation is further reiterated, as he and Ioan then devise a plan to go to the Danube Delta in Romania to set up a restaurant together, named “Ioan and Michele’s”. In an interesting turn of events, it is now the privileged male Westerner who longs to be part of another geographical space of which he is not native. [2] Shortly after this, the instability of the men’s employment becomes apparent as they both lose their jobs. After Michele is informed that he has been fired, Amoroso again reconfigures an earlier scene to juxtapose Ioan and Michele’s exclusion: this time with an extreme long shot of a disappointed Michele standing in the middle of the busy train station as Armani billboards loom at the top of the frame.

Constructing Identities

In her essay on “The New European Cinema of Precarity”, Alice Bardan maps out a contemporary filmic trend that responds “to the shifts in European labor practices, which allowed the dramatic increase in casual jobs and short-term contracts as opposed to long-term, secure job contracts with benefits” (71). She highlights:

Precarity is often understood as the condition of being unable to predict one’s fate, which translates in turn into an increasing inability to build social relations and feelings of affection. While this condition has existed for a long time, it currently references the diffusion of intermittent work across Europe. (72; emphasis in original)

Bardan here utilises the concept of the transnational in order to underline how this cinematic trend stretches beyond the national boundary across Europe. Moreover, in Western Europe, in particular, as Brett Neilson and Ned Rossiter note, “the notion of precarity has been at the centre of a long season of protests, actions and discussions” (no pag.). From a transnational perspective, then, Bardan describes a number of films from Italy (including Amoroso’s Cover Boy) and elsewhere in Europe in which precarious labour is represented as having crippling effects on the contemporary generation, and socioeconomic failures on a macro level are recurrently interrogated. As a result, these films “ultimately not only reveal contemporary Europe as a territory undergoing profound transformations, but also downplay ideologies of national consciousness and identity” (78).

Amoroso’s subversion of a “self”/”other” divide differentiates Cover Boy from the narrative and representative norms often featured within migration cinema, yet the parallels he draws between the socioeconomic situation of the native and the migrant fall in line with the tendencies to which Bardan refers, which “no longer show the importance of national identity and generally avoid presenting immigrants as struggling outsiders to the sacred national space” (86). Ioan, like Michele, loses his job as a result of being an undocumented migrant; thus, the characters’ situation becomes desperate. However, their subsequent search for new employment yields one of the film’s lighter moments, which interestingly draws attention to the transnationality of identity construction in the context of the East/West binary that Amoroso continually undermines.

In this sequence, Michele and Ioan attempt to obtain (informal) employment at a car wash business, where Michele pretends that he too is a migrant. Michele, uncertain of the believability of their scheme, is reassured by Ioan—after a quick inspection of the former’s appearance—that he will have no problem in passing as a migrant. What follows is a significant scene in which Michele must endure the degrading treatment to which migrants are usually subjected, where an Italian customer complains loudly about the way Michele is washing his car and blames his poor workmanship on what he was (or was not) taught in his own country. Interestingly, the car-washing machine behind Michele is in the same bright colours as the Romanian national flag and therefore places Michele in close visual proximity to Eastern migration.

Figure 3: Michele “performs” the role of migrant in Cover Boy. Paco Cinematografica, 2006. Screenshot.

This is further heightened as Michele gets his revenge on the bigoted customer by throwing a bucket of water over his head, before making his escape with his authentic Romanian companion. While Amoroso’s execution of this sequence is rather slapstick, the importance of Michele’s deviation—from his own nationality, as well as from his desperate willingness to work—should not be overlooked: firstly, because it recalls an earlier scene in which Bogdan gives Ioan new clothes in order for him to pass as an Italian; and, secondly, as Michele’s gesture of denationalisation reminds the viewer of his wish to migrate to Romania and, as a consequence, the film’s deviation from the upholding of an exclusive (Western) European identity.

Shortly after this, the narrative takes an abrupt turn when Ioan is approached in the street by Laura (Chiara Caselli), a commercial photographer who offers him a job as a fashion model and asks him to accompany her to Milan. Michele too finds a job, albeit another temporary contract as a janitor. When Ioan informs Michele that he is leaving Rome, the latter is visibly upset, before Ioan comforts him by recalling their plan of opening up a restaurant in Romania, and promises that he will return when he has enough money to buy a car. The men embrace tenderly, and Ioan moves to a luxurious new life in Milan.

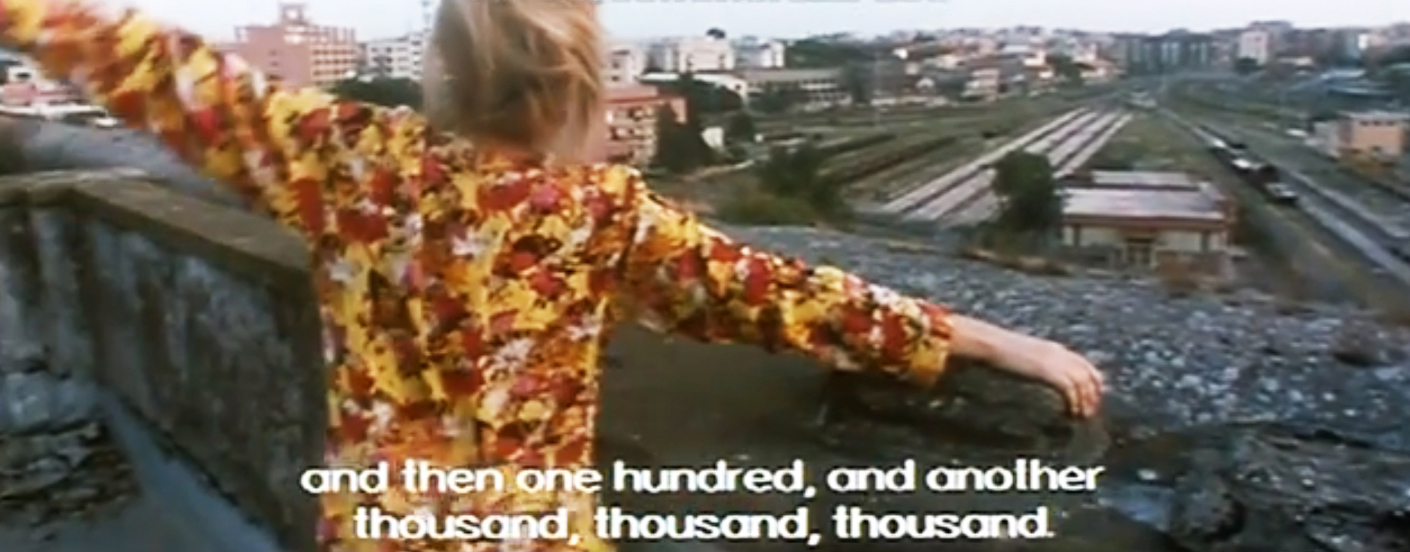

While the subtle presence of the Italian fashion industry—via Armani billboards—in the two aforementioned scenes stands in contrast to the human desperation and exclusion to which it serves as a backdrop, its more prominent presence here provides the opposite: the opportunity for wealth and inclusion, as Ioan is offered a job and eventually obtains a visa. Prior to this, however, Amoroso has almost cautiously emphasised the degree to which other, more secondary characters in the film have performed their way into a seemingly inclusive identity. This is most notably executed through the character of the landlady (Luciana Littizzetto) of the building in which Michele and Ioan live. While she is presented as an eccentric, and is thus central to the film’s more humorous moments, it is interesting to draw attention to the symbolic nature of her role as a failed actress and performer in light of the director’s utilisation of Italian geographical space and identity. One significant scene occurs on the roof terrace of the apartment building, where she theatrically performs a poem by Catullus. While looking out onto the cityscape of the Mandrione district, as if she were speaking to the city itself, she proclaims lines from “Catullus 5”:

Let us live, my Lesbia, and love.

And every wicked murmuring of the elderly, is worth infinity for us.

Give me a thousand kisses, and one hundred, and then a thousand.

And then one hundred, and another thousand, thousand, thousand. [3]

Figure 4: The landlady performs a poem by Catullus to the city of Rome in Cover Boy. Paco Cinematografica, 2006. Screenshot.

As in the earlier scene featuring the Roman gladiator, Rome through the ages, and thus the exclusivity of Italian/Western space, is represented with a degree of humour and falsity, as the “actress” who performs Catullus’s lines is similarly represented as a phony. It is also significant that the poem itself is about two lovers who should not give in to the rumours of others but who should instead continue to show their affection to one another and never reveal to anyone how many kisses they have shared. It may be argued that Amoroso’s inclusion of Catullus’s love poem simultaneously serves as a narrative signifier for Michele and Ioan’s relationship. While their friendship never becomes a sexual or conventional romantic relationship, at the end of the film Ioan ultimately chooses the love and support of Michele over the heteronormative (and financially prosperous) arrangement that is available to him with Laura in Milan. Yet the poem also alludes to the necessity of secrecy, which, along with the earlier allusions to Michele’s closeted sexuality, further compounds the notion of the “otherness” of the Italian native.

The recurrence of performativity, while mostly presented in a humorous way, tends to simultaneously allude to the broader theme of individual and national/collective identity. [4] This also surfaces in a scene where Michele is using the telephone in the landlady’s apartment, deceitfully reassuring his mother that he is employed and that his situation is prosperous, before the landlady scolds Michele for lying. A brief argument ensues, and when Michele confronts the landlady about her profession as an actress, she informs him that the reason she is not famous, and thus not being showered with awards at Cannes, is because she did not sleep with anyone to further her fame—this, she comically suggests, is a well-known fact within Italian cinema circles. The idea of having to sell oneself in order to be part of one of the nation’s most revered art forms is therefore playfully alluded to. Yet it also initiates the much darker theme of compromising one’s integrity and authenticity that arises when Ioan moves to Milan to become a fashion model.

Reconfiguring the East/West Dichotomy

As outlined in the Introduction, Amoroso’s use of reconfiguration in Cover Boy serves an integral role in its aesthetic. Until Ioan moves to Milan, this is executed through the use of archival footage, grounding the film’s sociopolitical concerns from the outset, as well as through a “reinstatement” of earlier scenes/events in the film. In a similar manner as when Ioan arrives in Rome, the camera encircles his arrival in Milan while drum beats fill the soundscape—although this time the sound is being produced by a Hare Krishna group instead of buskers on the streets of Rome. In all, the sequence is more celebratory, and it is not long before the camera turns its attention to the luxury in which Ioan now finds himself, again differentiating it from the introductory Rome sequence. Another instance of Amoroso’s recalling of prior filmic events begins before Ioan’s departure from Rome, when he is reunited with Bogdan in Piazza della Repubblica. The latter offers Ioan a job in “marketing”, which turns out to be prostitution, where the only requirement by the awaiting client is that Ioan is clean. This is then rehashed in a later scene in Milan, wherein Laura states that she was drawn to Ioan’s cleanness, which is why she has invited him to work with her. Interestingly, both Laura’s and the client’s domestic spaces are presented in marked contrast to the dark, rather dilapidated interior of Michele’s apartment in the Roman periphery, in that they are pristinely white and light-filled—an aesthetic purity that enhances their desire for cleanliness, but stands in juxtaposition with what unfolds as an impure desire to objectify and ultimately commodify Ioan’s body, albeit in differing ways.

Laura’s objectification of Ioan begins from afar in a scene in Rome, which initiates Amoroso’s more forceful use of mediality as a vehicle for the themes of mobility and the constructedness of identity. Our view here takes on the gaze of a camera lens and the unidentified photographer behind it. The idea of surveillance and endangerment, given how the lens resembles the barrel of a gun, is immediately evoked and is further enhanced by the aural emphasis on the camera shutter. We subsequently learn that the camera belongs to Laura, after which Ioan’s first encounter with her occurs. This precedes two crucial scenes in the context of Ioan and Laura’s working and intimate relationship, which bring to light the problematisation of Ioan’s individual and national identity as a result of his inclusion in the performance of one of Italy’s most consumption-driven industries.

The first occurs when Ioan is modelling in a fashion show, where the diegetic music that plays as he walks down the catwalk evokes the moment when he witnesses his father’s murder on the street in Bucharest. The song playing is Audio Bullys’ “Shot You Down”, a remix of Nancy Sinatra’s version of “Bang Bang”, in which the loud sound of two gunshots features prominently while Sinatra’s voice is heard singing the lyrics “Bang bang. My baby shot me down”. Aurally, this clearly recalls the two loud gunshots that ring out as Ioan’s father is gunned down at the beginning of the film, which, as a consequence of its evocation in this scene, along with the fact that the song itself is a remix, reiterates Amoroso’s technique of reconfiguration to establish the film’s overall sociopolitical message.

In a later scene, Ioan wakes up to find that Laura had been taking photographs of him while he was sleeping, and she continues to do so when he stands up to stretch, even though he appears uncomfortable. Again, there is an aural emphasis on the camera shutter, recalling the first scene in Rome when Laura is taking photographs of an unknowing Ioan, as well as the sense of endangerment inherent in it. Similar to the framing of the shots in Rome and the aural elements of the earlier catwalk scene, the camera-as-gun analogy is further intimated here as she asks him to keep his arms raised while she takes photos of his naked, upstanding body. It is subsequently revealed that Laura worked as a photojournalist during the Romanian Revolution; as Ioan is clearly interested in this work, a brief conversation ensues before she dismisses Ioan’s memory of it because of his young age. In the final Milan sequence, we see that Laura has digitally manipulated the image of Ioan’s naked, stretching body onto an old photograph that she took during the Romanian Revolution, where a soldier is pointing a gun at a civilian on the street. This new, remixed image is unveiled at the launch of what appears to be a new clothing line, where the words “Exile: Wear the Revolution” are typed across it. [5] Ioan is disgusted by her disrespectful treatment of his national and personal history and her commodification of his body through the unethical reconfiguration of a historical image, and leaves immediately in his new car to return to Michele. By this point, however, Michele has lost his contract work yet again and, having become desperate on account of his financial situation and without the support of the man he loves, he kills himself before Ioan’s return.

Figure 5: Ioan’s image superimposed by Laura for an advertising campaign, placing the dark history of the Romanian Revolution in ideological proximity to the consumer-driven present of contemporary Italy. Cover Boy. Paco Cinematografica, 2006. Press Material.

Deviations and Desires

In a recent overview of Italian migration cinema and its representations of the male, non-EU “other”, Duncan has convincingly argued for the valuable utilisation of queer theory in exposing the impossibility of cross-national romantic encounters in an Italian context, specifically looking at representations of the Eastern European male migrant. He suggests of his case studies that their filmmakers have aligned themselves to the cause of positively welcoming Italy’s new residents, and also points out how this filmmaking has its roots in postwar neorealism and its project of nation-building (168). This “queerness”, he suggests, “emerges through the conflict between normativities of sexuality and race that find themselves refigured through the process of contesting the nation in a postcolonial context” (170). While the main subjects of his case studies are not shown to be anything but heterosexual, in that their desire is for the affections of female characters, the “queerness” of their sexuality stems from their distance from the idea of the heteronormative family, which functioned “as the symbolic microcosm of the nation” in postwar neorealist filmmaking (170). The success of the characters’ romantic desires would essentially, in varying ways, assimilate them into Italian society.

Yet through the films’ insistence on the impossibility of cross-national love, it becomes an unfeasible arrangement—a theme also taken up by Áine O’Healy in her essay on “Screening Intimacy and Racial Difference”, through which a trend in contemporary Italian migrant cinema is clearly established. As Duncan continues:

The persistent failure of these romances clearly represents the incompatibility of the non-Italian in Italy. There is clearly a strong repetitive element here in an otherwise varied corpus of films. It is also an element that ruptures the realist or referential claims to represent the contemporary Italian situation where many migrants do, in fact, marry and stay on. (173)

In turn, “the distance [these characters] stand from the heteronormative family” is emphasised (Duncan 170). Here, I suggest that Amoroso subverts the trope by drawing attention to Michele’s “otherness”, something that has been intimated throughout the film with allusions to his hidden sexuality. This is also more solidly established during a sequence towards the end of the film, in which the “impossibility” of his socioeconomic situation is conveyed. Pertinently, in one such scene we see his contractor tell him that employees with families must be prioritised. As such, the idea that Michele is being punished because his situation is nonnormative—regardless of whether his employer knows that he is queer or not—is thus implicitly suggested. Moreover, up until the point of his death, he and Ioan are about to be reunited and, by virtue of both of them having rejected heteronormativity in different ways, as well as what is on offer to them in the West, are about to realise their dreams together. While, unlike Michele, Ioan is not represented in any concrete way as gay or bisexual, I suggest that Duncan’s argument that “queerness” can unearth “how constructions of non-normative sexuality function to mark the symbolic limits of national belonging” can be extended to Amoroso’s dual othering (180).

With this, Amoroso also subverts the usual trope of desire that is associated with the new settler, in that, as Duncan notes, films “about migrants portray them invariably as desiring subjects” (173). This subversion has already been initiated by Ioan’s blasé sentiments about leaving Romania in the first nonarchival sequence of the film, and continue with Michele’s desire to migrate East, differing from the tendency to portray the migrant as someone whose “primary desire”, as Duncan continues, “is for Italy itself, a kind of spatial eroticism, or topophilia” (173). Here, however, heteronormative and thus Western assimilation ultimately serves, most overtly, as a threat to Ioan’s identity and, through the three examples of the camera-as-gun analogy during his time with Laura, as perhaps a threat to Ioan’s life. It is, however, Ioan who escapes, while Michele’s demise is due, in part, to his socioeconomic desperation.

Europe of “Others”

Recalling Bardan’s observation of precarity in contemporary European cinema, Cover Boy “downplay[s] ideologies of national consciousness and identity” through Amoroso’s underlining of the plurality of European “otherness” (78). But it is in the figurative intervention of the Italian nation and Amoroso’s interrogation of the solidity and exclusivity of a European identity towards the end of the film that the director’s trope of identity construction and its links with social inclusion reach a striking climax. Going beyond the theme of precarity and its representational motifs, however, my closing analysis will focus on Bauman’s “Europe of Strangers” as another way of reading the film within a European paradigm, allowing us to further conceptualise Amoroso’s technique of aesthetic reconfiguration and identity construction in a transnational European context.

In the film’s penultimate sequence, Ioan is on the telephone to the landlady asking her to pass on his urgent message that he is returning (which is never received), while a dejected Michele lies shirtless on the couch in his apartment downstairs with the television blaring. The lighting in his apartment is dark except for a light next to where he lies, shadowing the frame in a somewhat claustrophobic tone; an extreme close-up of his eyes lets us know of his melancholic state, while his restless body suggests that he is contemplating something serious. The voice of Silvio Berlusconi blasting from the television set is unmistakable, as he crudely criticises the Left’s economic policies and seems oblivious to the fact that Italy is undergoing a socioeconomic crisis. Once more, the aural aesthetic of Amoroso’s mise en scène plays a crucial role in his explicit and implicit sociopolitical commentary. Bardan and O’Healy have highlighted that Berlusconi’s speech clearly serves as a catalyst for Michele’s eventual suicide, which stems from the “clash between Michele’s assumed superiority as an Italian (which is the subtext of his early conversations with Ioan) and the realization that he is as powerless as many immigrants” (10). [6] Amoroso also draws his technique of reconfiguration to a sociopolitical close here, coming full circle from his assembly of nonfiction footage in the film’s opening sequence. He has the last word on Berlusconi’s harsh regime, through an underlying juxtaposition between the desperation and turmoil of the Cold War with the critical state of Italy from a labour perspective and, as a consequence, its treatment and othering of “its own” in contemporary times. As noted in the Introduction, the Berlusconi government’s policies on film funding influenced Cover Boy from the outset while here, diegetically, the ideologies of his reign are ultimately likened to those of a pre-1989 Eastern dictatorship. Initially, Amoroso was prevented from shooting a substantial part of the film in Bucharest and now, within the diegesis, Berlusconi’s voice “prevents” the Italian protagonist from migrating East.

Relevant to the broader theme of collective identity is Bauman’s suggestion that national identities “no longer feel secure, while European identity is nowhere near offering the standards of security once set by the nation-states” (6). He proposes that this is due to the “waning” of governmental control over their territories as a result of global capital, whereby the wellbeing of the nation’s citizens is now in the hands of “market forces” (5). As he outlines:

The order of things protected by the state has lost much of its aura of tough and indisputable reality. Order no longer appears preordained, self-evident, secure. Nations can no longer rely on state protection; the well-being of national identity, or any other identity for that matter, is no longer safe in the national governments’ hands… (5–6)

On a more specific level, then, Bauman links the individual “identity problem” to the instability of living a precarious life—a problem that is widespread and increasing across Europe, where employment and thus identity are in crisis (7). While the crises of individual and collective identities, as he suggests, “do not stem from the same root”, it is psychologically that they tend to “collapse and blend” (8). As a consequence, the crisis of individual identity seeks a solution in the “postulated security” of a collective identity (8). Yet who is to blame for the disruption to individual security? As the global markets are invisible to the eye, Bauman suggests that through “tangible, close-to-hand experience[s]”, blame is laid with another, more visible “threat” to collective identity—the migrant, the foreigner, the “stranger next door” (8).

As Bauman argues, it is the inclination of the political classes to “divert the deepest cause of anxiety, that is the experience of individual insecurity, to the popular concern with (already misplaced) threats to collective identity” (10). Cover Boy’s penultimate sequence juxtaposes Berlusconi’s crude comments on how the Left will exploit workers if permitted to do so, which divert attention away from the current socioeconomic crisis, with Michele’s embodiment of the individual “identity problem” to which Bauman’s theories draw attention (8). The concept of a collective identity is thus undermined here via the aural rhetoric of Berlusconi and the visible, tangible evidence of individual desperation and insecurity.

A crumbling Eastern European system of identity is critiqued via archival footage at the beginning of Cover Boy, and the film concludes with a collective national identity of the contemporary West being interrogated, where the only alternatives offered are to die or to migrate to the East. While Michele meets his demise before he gets the chance to migrate, by returning to Romania Ioan has escaped the gun-like force of Laura’s camera and a consumer-driven society, along with a deviated version of his own personal, national history and identity.

Notes

[1] It could be argued that a later scene in which Ioan makes love with a woman is offered in contrast to the tender moment that he and Michele share, in that the former is depicted rather clinically and the latter in a more sensual way via the fluid camera, the blurry, watery surroundings, the close-ups of the men’s bodies and the affection they show to one another.[2] That is not to say that this in itself is unique. Another, earlier example of Italian (temporary) migration to the East can be seen in Il toro (The Bull) by Carlo Mazzacurati (1994).

[3] This translation is from the subtitles provided in an excerpt of the film on YouTube: “Cover Boy – Luciana Littizzetto and Catullo (English Subtitles)”.

[4] Other elements of the mise en scène in Cover Boy should also be highlighted in the context of the theme of performance: firstly, through the name of the landlady’s dog, Stanislavski—referencing Russian actor and theatre director Constantin Stanislavski, who developed the famous method of acting wherein one draws from emotional memory in order to portray emotions in a given performance, further emphasising the intertwining of East and West that occurs throughout the film; and, secondly, the large poster for Wim Wenders’s Paris, Texas (1984) hangs on the wall of the actress’s apartment. Furthermore, Bardan and O’Healy have discussed that the film’s tagline, which was used in its initial advertising, makes obvious reference to the cinema of Pier Paolo Pasolini as “Amore e rabbia di una ‘generazione precaria’” (“Love and Anger of a ‘Precarious Generation’”) evokes Pasolini’s La rabbia (Rage) from 1963 (21). This cinematic reference is also worth noting on account of Cover Boy’s political leanings.

[5] Bardan and O’Healy observe that the “Exile” poster “invites multiple visual associations” through both its similarity to the United Colors of Benetton advertising campaign that was circulated internationally during the late 1980s/early 1990s (12), and the “Global Warming Ready” campaign by Diesel Jeans, which circulated at the same time as the film’s release (13).

[6] Bardan and O’Healy provide a full translation of the portion of Berlusconi’s speech that plays in the background of this scene, which originally took place at a manufacturing conference in March 2006 in Vicenza:

The crisis exists only in the desire of the Left—in their newspapers they’re inventing [a story of economic] decline so that the Left can come to power. But you should know that when they attain power they will construe corporations as machines that enable the exploitation of people by other people; they will regard profit as the devil’s excrement and will maintain that saving money is not a virtue, as it is for us, but something that should be taxed and penalized. (22)

References

1. Amoroso, Carmine. “Cover Boy – Luciana Littizzetto and Catullo (English Subtitles).” Online Video Clip. YouTube. YouTube, 7 November 2010. Web. 26 July 2015. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SodfmiIKSU>.

2. As You Want Me [Come mi vuoi ]. Dir. Carmine Amoroso. Mediaset, 1997. Film.

3. Bardan, Alice. “The New European Cinema of Precarity: A Transnational Perspective.” Work in Cinema: Labor and the Human Condition. Ed. Ewa Mazierska. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. 69–90. Print.

4. Bardan, Alice, and Áine O’Healy. “Transnational Mobility and Precarious Labour in Post-Cold War Europe: The Spectral Disruptions of Carmine Amoroso’s Cover Boy (2006).” Academia.edu. Web. 27 July 2014. 1–22. <http://www.academia.edu/4167298/TRANSNATIONAL_MOBILITY_AND_PRECARIOUS_LABOUR_-co-written_with_Aine_OHealy>.

5. Bauman, Zygmunt. “Europe of Strangers.” University of Oxford. Transnational Communities Programme, 1998. Transcomm.ox.ac.uk. Web. 10 June 2014. 1–16. <http://www.transcomm.ox.ac.uk/working%20papers/bauman.pdf>.

6. The Bull [Il toro]. Dir. Carlo Mazzacurati. Penta Films, 1994. Film.

7. Catullus, Gaius Valerius. “Catullus 5.” The Poems of Catullus: A Bilingual Edition. Trans. Peter Whigham. Berkeley: U of California P, 1983. 55. Print.

8. Cover Boy. Dir. Carmine Amoroso. Paco Cinematografica, 2006. DVD.

9. Duncan, Derek. “Loving Geographies: Queering Straight Migration to Italy.” New Cinemas 6:3 (2008): 167–82. Print.

10. Neilson, Brett, and Ned Rossiter. “From Precarity to Precariousness and Back Again: Labour, Life and Unstable Networks.” Fibreculture 5 (2005): no pag. Web. 10 July 2014. <http://five.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-022-from-precarity-to-precariousness-and-back-again-labour-life-and-unstable-networks/>.

11. O’Healy, Áine. “Screening Intimacy and Racial Difference in Postcolonial Italy.” Postcolonial Italy: Challenging National Homogeneity. Eds. Cristina Lombardi-Diop and Caterina Romeo. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. 205–20. Print.

12. Paris, Texas. Dir. Wim Wenders. Road Movies Filmproduktion, 1984. Film.

13. La rabbia. Dirs. Giovanni Guareschi and Pier Paolo Pasolini. Opus Films. 1963. Film.

14. “Shot You Down.” Perf. Audio Bullys. Generation. Source, 2005. CD.

Suggested Citation

Keating, A. (2015) 'Europe of “others”: deviations, mobility, and the construction of identities in Carmine Amoroso’s Cover Boy', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 9, pp. 58–73. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.9.04.

Abigail Keating is Lecturer in Contemporary Film and Media at University College Cork. She has published widely on European cinemas and other areas of cinema, screen media and culture, and is a cofounding member of the Editorial Board of Alphaville.