“Remembrance”:Reticence, the Sensual, the Erotic, and the Music for The Irishman

Robynn J. Stilwell

[PDF]

Abstract

Robbie Robertson’s score for The Irishman (Martin Scorsese, 2019) emphasises the film’s underlying contemplation of impending aging and death. Building on Danijela Kulezic-Wilson’s concepts of reticence, sensuality, and eroticism, this analysis explores the collaborators’ converging stylistic relationship to reticence and proposes a distinction between the “sensual” (an immediate appeal to the senses, residing particularly in timbre, texture, and sonic space) and the “erotic” (a temporal unfolding of anticipation, expectation, evasion, and fulfillment), all concepts richly represented in the score. Two primary cues—the “Theme” that punctuates the narrative at key points and the end-title music, “Remembrance”—share a bluesy aesthetic, but break through the style’s predictable responsorial, circular forms: the “Theme” takes a minimalist approach, the erratic phrasing of its tenuous texture thwarting expectation and building suspense, even dread; in “Remembrance,” three virtuoso blues guitarists solo individually and yet together, abandoning traditional call-and-response and cutting competition to join into a heterophonic communal lament, peaking in an ecstatic release of grief and a reflective recovery of breath.

Article

Time is a thread in the fabric of spacetime, marked out in measured units by objective means for Western culture; but as individuals, we experience its flow subjectively, its speed altered by our experiences and our emotions.[1] Music is a way of manipulating our experience of time, a feature at the root of much of its usage in cinema; but certain life events will cause you to remap that flow, not just going forward but looking back. Losing Danijela was one of those moments: she was important to me as a person, but also as a colleague whose work nudged against mine in sometimes delicate yet profound ways.

I am using “Danijela” as the referent here because the academic Dr Kulezic-Wilson is not really how I knew and thought of her. Even when thinking of her work, I thought of it as “Danijela” because I absorbed most of it directly through her—whether through conference presentations, talks at dinner, or moments lingering in the corridors at NYU at Music and the Moving Image each spring. Reading the work was just a revisiting of that first-hand dialogue. She was of a younger academic generation, giving me insight into changes that were afoot, and making me aware anew of ideas that I had learned to hide in order to be “taken seriously” by musicology, a field I wanted to love but that didn’t always love me.

Danijela brought back to the surface some sublimated passions about music and ways of expressing how music affected me that had been metaphorically beaten out of me as a music student in the 1980s: emotional evocations, physical and kinetic responses, fragments of and allusions to narrative within abstraction. Red marks on papers and frowns from my teachers and even eyeballs from some classmates told me that these subjective responses were illegitimate: objectivity only, please. And I did benefit from that discipline—learning to parse music through harmonic, pitch-oriented, and structural frameworks does have communicative power, the same way that knowing grammar, meter, rhyme schemes, alliteration, assonance, colour theory, and concepts of proportion, perspective, and perception aids discussion of literature or painting.

I want to re-embrace that physicality of music and its affective qualities that Danijela revelled in: the sensuality of the timbres with their invitation to touch; an erotics of listening in the relationship of the listener and the film-text. I want to nuance her terminology, drawing some distinction between the sensual and the erotic, between touch (the haptic) and feel (the kinetic), expanding sensation from the tactile to the experience of movement—the impulse to dance, but also the unfolding of music through spacetime in structural listening that is both an intellectual recognition of architectural processes and a proto-narrative suspense as we anticipate resolutions that deflect, frustrate, or fulfil our expectations.

Robbie Robertson’s music for Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019) has a spare but dynamic musical texture with a deceptive temporal unfolding; it both comports with and diverges from the conventional Hollywood leitmotivic score, and it also suggests engagement with another term from Danijela’s work—reticence, although again, in a slightly different way from Danijela’s usage. To me, the greatest tribute one can give to another’s scholarship is for its lens to refract the way you think, and I would not necessarily have thought of “reticence” without her adoption of the term. But both in the placement of the music and in the restrained quality of the music itself, The Irishman’s represents a kind of musical reticence.

Reclaiming the Physical

Intellectually, I was born into the gap between “historical musicology” and “critical musicology”, or as it was styled then, the “new musicology”. In the year between my Master’s degree and the beginning of my PhD, two important new voices (perhaps significantly, both female) appeared: Claudia Gorbman, with her seminal book on music and narrative film, Unheard Melodies, and Susan McClary, particularly her work on Beethoven and sexual violence (“Getting Down”) and on the cultural power of the canon and the avant-garde (“Terminal Prestige”). These works, I felt, did not so much change my way of thinking as bring the field of musicology into focus with my ways of thinking, as someone whose interests had tended to lie outside the musicological canon—particularly with popular music and music in relationship to other media (film, television, theatre, dance, and the emergent music video).

It was really only in the second decade of the twenty-first century that Danijela’s work,[2] together with that of Anna-Elena Pääkkölä,[3] brought the “haptic” back into my discourse of music. As a doctoral musicology student in a modernist art history graduate seminar, I had been particularly fascinated with Cezanne, that in-between-ness intersecting impressionism and cubism, drawing me to write on Cezanne and early Mahler. I relied primarily on the similarities of Mahler’s orchestration and Cezanne’s broken planes, but in the back of my mind were also the fuzzy surfaces of Cezanne’s peaches and the gruff crunch of a bass downbow in the scherzo of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, evoking a rustic dance.

Here, I am going to place a metaphorical wedge to separate the “sensual” and the “erotic”. In Danijela’s work, she tends to a symmetry, a complementary relationship between the two terms, between the sensual textures of the film body and the erotics of the audience responding to those haptic inputs during the cinematic experience of an integrated score (94–95). I would like to make a distinction between the purely textural/haptic, sense-based “sensual” pleasure of interacting with the sonic materials and a more directed, time-dependent, narratively tinged unfolding as the “erotic”. Michel Chion describes “vectorization” as an orientation toward a goal, or at least a future through music (13–14), and I would posit that this can elicit a kind of eroticism: a suspense that draws one forward but also provokes pleasure in the moment.

Reticence

In theorising “reticence” (59), Danijela drew on the writings of Russian film directors like Alexander Sokurov and Andrei Tarkovsky, who put an emphasis on “a limitation of what we can actually see and feel” (Sokurov qtd. in Jaffe 35), and an assertion that to be art, “something must always be left secret” (Tarkovsky 110). Thus reticence, usually delegated to a director, bears an affinity with Roland Barthes’ concept of the “writerly” text, which with its concentration on a self-consciously elaborate use of language might seem to be an opposite; both, however, invite an active engagement from the audience/reader, rather than allowing passive absorption.

I like the use of a word like reticence—it’s not unfamiliar to most, but is also not too familiar. In that way, it has a reticence itself: not quite jargon, but invested with a certain specificity in the right context. But it is, itself, just a little challenging as an analytical concept, in that the emphasis on “limitation” or “absence” elides the presence of a/the creator, since in common usage, we tend to use the term as an attribute of a person rather than a text. Danijela’s use of “reticence” prompted me to think about the nearly fifty-year Scorsese-Robertson collaboration: for Robertson, reticence was a long-standing aspect of his musical expression; but for Scorsese, it is a relatively new—and in the case of The Irishman, perhaps surprising or even shocking—attribute.

A hallmark of Scorsese’s directing style has been his lavish use of music, not surprising given his love of Powell & Pressburger films and Hollywood musicals. But Scorsese was also at the forefront of breaking the classical Hollywood resistance to foregrounded popular music. This became a feature of the so-called “New Hollywood” of the late 1960s and 70s, beginning with films like Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) and Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point (1970),[4] but Scorsese’s Mean Streets (1973) used the music with more cinematic energy and narrative import. While in Hopper’s and Antonioni’s films popular music was often a nondiegetic bed into which images are laid, Scorsese moved the camera and edited to the music more intentionally: in Mean Streets, he introduces Robert De Niro’s Johnny Boy in an iconic sequence that unfolds in the fantastical gap, accentuating its subjective power. In a bar suffused with deep red light, the Rolling Stones’ “Jumping Jack Flash” is conceptually diegetic, but sonically all-encompassing in the manner of nondiegetic music. The opening riff’s harmonically suspended introduction is matched to a long push-in on Charlie (Harvey Keitel) that may or may not be in slow motion, creating a temporal tension with the diegetic music; the reverse shot of an inebriated Johnny Boy entering with a young woman on each arm confirms the slow motion and thus the subjectivity residing in Charlie’s gaze—whether he is envious or exasperated is unclear, an ambiguity that pervades the relationship at the centre of the film.

Figures 1 (above) and 2 (below): Charlie watches Johnny Boy enter the bar to “Jumping Jack Flash”

by the Rolling Stones. Mean Streets, dir. Martin Scorsese. Warner Brothers, 1973. Screenshots.

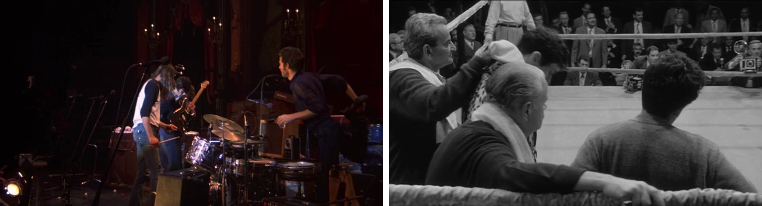

This musicality was one of the main reasons that, in 1976, Robbie Robertson, then guitarist and primary songwriter of the seminal rock group The Band, asked Scorsese to film a record of The Band’s final concert, with many notable guests, including Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, and Van Morrison. The resulting film, The Last Waltz (1978), is not simply one of the most highly regarded concert films in history; it impacted Scorsese’s career in two interconnected ways: filming the musicians gave the distinctly nonathletic Scorsese a view on how to film the fights in what would be his next film, Raging Bull (1980); and he and Robertson would become close friends and collaborators.

Figures 3 (left) and 4 (right): In the ring: Scorsese’s filming of The Last Waltz

—staying on stage with the musicians even between numbers (“like boxers between rounds”), catching the audience only peripherally if at all—gave the director a framework for filming Raging Bull.

The Last Waltz, United Artists, 1978. Raging Bull, Chartoff-Winker Production, 1980. Screenshots.

Reticence is about having something to express, but holding back, often implying a sense of the author in question observing, judging, choosing their moves carefully. This certainly resonates with Robertson’s career, as restraint had been a feature of his music-making since the late 1960s, when he “got down off the wailing wall” after blazing a path as an electric guitar pioneer. Born in Toronto in 1943, the son of a Cayuga-Mohawk mother and an Ashkenazi Jewish gambler who was killed in a somewhat suspicious hit-and-run accident before Robertson was born (his connection with Scorsese seems almost genetically fated), Robertson wrote two songs at age fifteen that were recorded by Arkansas rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins, who was hugely popular in Toronto. Recognising the boy’s “po-tential” (Hawkins’s emphatic inflection) as a songwriter and a hard worker, Hawkins hired him to be in his band, The Hawks. Robertson eagerly absorbed the direct and indirect lessons of transitory bandmates like Fred Carter, Jr., and Roy Buchanan, and musicians who toured the same circuits, like Bo Diddley, Howlin’ Wolf, and Hubert Sumlin. He developed a style both wild and precise, wielding a Fender Telecaster like “a thug’s jackknife” (Wheeler).

The Hawks eventually left Hawkins, and after a couple of years as a touring bar band, hooked up with Bob Dylan on his infamous “going electric tour” in 1965–66; afterward, they transformed into The Band, playing a combination of blues, rhythm & blues, folk, country, jazz, gospel, and funk with a remarkable ensemble chemistry, both tight and loose; they were musicians’ musicians, influencing, among many others, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, Pink Floyd, and Led Zeppelin.

Having felt that his wild soloing on tour with Dylan was like a “premature ejaculation” (Bowman), Robertson consciously buried his guitar in the texture of The Band, from spider-silk filigree to piercing little bends and stabs to rattling steam-engine rhythms overlaid with lead riffing. Even overt solos are marked by deceptive simplicity, whether the mandolin-like “Unfaithful Servant” or the long-breathed arcs of “To Kingdom Come”.

That reticence seems at odds with Scorsese’s musical excess, but could also have generated productive tension as they sought new ways of setting music into films. Even after nearly five decades of collaboration, Robertson often commented that each film with Scorsese was a new experiment. One constant request from the director was that “it shouldn’t sound like film music”; Robertson often clarified, “we admire that, but don’t know how to do it.” And it is also true that the “classic” Hollywood style has become less effective, and even potentially alienating to modern audiences (Gorbman, “Music”, qtd. in Kulezic-Wilson 68). Robertson’s contributions varied widely, from underscoring to original source music to producing new recordings with other artists, although most public recognition went to his curation of popular music from a broad historical range; he performed a similar task with modernist, post-modernist, and minimalist art music for Shutter Island (2010). In films like Casino (1995) and The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), the amount and variety of music, complemented by virtuosic camerawork and editing, is almost overwhelming.

But the 2016 film Silence marked a notable shift. The title alone is suggestive (Robertson joked, “Marty, maybe I’m already done!” (Howell)), and the story about seventeenth-century Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in Japan demanded a different approach to music, something that Danijela would definitely recognise with her definition of “reticence”, blending score and sound design. Robertson called it “more of a soundscape: I have Portuguese hymns, written in the 1600s, played backward, with Japanese Taiko drums ripping them apart” (Levine). The underscore executed by Kim Allen Kluge and Kathryn Kluge includes a great deal of ambient sound (rain, wind, waves, insects).[5] The kind of explosive popular music interjections that are so iconically “Scorsese” are inappropriate not just historically but thematically.

Their next film, The Irishman, is a return to the gangster milieu of Scorsese’s best-known material, but with a marked new restraint of means. Instead of revelling in the glamour, the film emphasises the everyday grind and develops into a rumination upon aging—appropriate for the collaborators. Scorsese, Robertson, and actors Robert DeNiro, Al Pacino and Joe Pesci were all in their late seventies by then, a fact ironically emphasised by the use of deaging CGI. The Irishman has the expected curated song score, but there are far fewer musical moments than one would expect from Scorsese. The newly composed underscore is likewise terse, primarily a theme that recurs at key narrative points.

Sensual, Erotic, Haunting

Robertson’s compositional style is not, strictly speaking, minimalist, but it has strong affinities with the technique, particularly a deceptive simplicity. But, unlike the sometimes cold, mechanistic connotations of minimalism, Robertson’s roots in blues and funk combine to a different affect—although not dissimilar to Robert Fink’s recuperation of the libidinal energy of minimalism through the lens of disco (and vice versa) (25–61). Throughout Robertson’s entire career, references to “spooky” and “eerie” recur regularly alongside both sensuality and overt sexuality,[6] if not downright raunchiness: Nick DeRiso calls “Yazoo Street Scandal” (1968) “harrowing, carnal”; of Robertson’s first, self-titled solo album (1987), Jay Cocks wrote that “Robertson came up with a silky, soaring sound that is ethereal and sporting at the same time, just what you might hear from a roadhouse located down an off ramp just south of the pearly gates”; Hal Horowitz notes the “foreboding and slinky sense of sexuality” in the song “Walk in Beauty Way” from 2019’s Sinematic; and Chris Willman, writing of the New Orleans-steeped Storyville (1991), states simply that “mixing the earthy and ethereal is the ex-Band leader’s stock in trade.” Comparisons to Ennio Morricone are also not unusual: “Like Ennio Morricone, he has a gift for sound that’s both stately and hip, primal and intricate” (Corio). Morricone’s background was, like Robertson’s, heavily influenced by the recording studio and popular music production, and both tend toward a foregrounded treatment of distinctive sounds within “widescreen” soundscapes.

Robertson’s textures are almost always tenuous and spacious, with a few instruments marking out widely separated ranges and timbres that appeal immediately to the sensual; reviews often recommend headphones for audibility of detail and better point-of-audition placement in the mix, and his solo music and film scores pop up frequently as test plays in reviews of stereo equipment, even though some of it is now decades old.[7] Both the expansiveness—which can foster a sense of freedom and exhilaration, or the uneasiness of feeling exposed—and the laid-bare instrumental lines present distinctly different haptic timbres. The “Theme from The Irishman”, with its combination of drum kit, harmonica, bowed double bass, and almost imperceptible acoustic guitar provides both a vast, dark sonic space and a rich variety of distinctive sensory inputs; and the closing “Remembrance” features a similar instrumentation with three electric guitarists, each with distinctly different touches and tones.

Much of Robertson’s music features transparent but vivid textures, long-breathed lines with unexpected but satisfying voice leading,[8] and rhythms that subtly undermine the superficial impression of regularity, all of which foster a musical eroticism in the tension between the urge to move forward and the pleasure in lingering on an individual moment—a passing dissonance, a long-delayed rhythmic resolution, a line that evades expectations only to curve back from a different direction. Robertson had a particular affinity for a musical form known as a “patrol”, which imitates the passing of a parade before the listener, deploying an inexorable rhythm that increases in dynamics and intensity (usually through contrapuntal development) over repeated stanzas, peaking and then receding, as if passing into the distance—one can easily see the confluence of this form with an erotics of listening.[9]

Notably, Robertson’s music rarely reaches a conventional, quasi-orgasmic “release”: it might simply fade out (“Unbound”) or achieve a kind of blissful plateau (“Walk in Beauty Way”). Two pieces that do climax and then subside are not so much orgasmic as grieving: “Reflection (Adagio)” from the soundtrack of Ladder 49 (Jay Russell, 2004), a post-9/11 film about firefighters and the impact of their sacrifice on those left behind; and “Remembrance”, a piece originally written in memoriam for Robertson’s friend, cofounder of Microsoft and philanthropist Paul Allen. Scorsese then asked if they could place the piece end of The Irishman, where it becomes an elegy for main character Frank Sheeran (Robert de Niro), or for murdered labour leader Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino), or even their way of life and living. This arc of grief is also one that many of us can recognise in our experience of mourning.

Theme for The Irishman

One of the challenges Robertson acknowledged in writing a theme for The Irishman was that, as the story winds through the decades, the film had to avoid the specificity of the historical time. This was an unusual charge, simply because one of the features of Robertson’s contributions to Scorsese’s films was his canny, but not always obvious, selection of time-and-place specific music.

The “Theme” has an out-of-time-and-place quality inherited from both the Spaghetti Western and Robertson’s blues foundation; it hints at the patrol form, though builds primarily through rhythmic/metric tension rather than textural complexity. In the film, Scorsese doles out sections of the theme for key scenes, a process he often employs that would have destroyed a large-scale structure, but Robertson’s manipulation of temporal and timbral musical expectations works both locally and over the length of the piece. The tension between minimalist repetition and blues gestures recalls Susan McClary’s exploration of minimalist scores for The Hours (Stephen Daldry, 2002), Angels and Insects (Philip Haas, 1995), and The Piano (Jane Campion, 1992) that nonetheless integrated romantic tropes; the repetition of tropes connoting romantic passion thwarted expected resolution in narratively productive ways (“Minima Romantica”). Robertson similarly channels musical desire into unease and suspense. The theme recurs at key points in Frank’s journey into organised crime and his relationship with teamster leader Jimmy Hoffa.

The four instruments—drum kit, harmonica, acoustic guitar and double bass—might all be found in a blues band, and the melody’s shape and performance style have a blues tinge; the melodic structure is even AAB and suggests a blues progression, though highly distilled. The drum kit’s cadence, played by legendary session drummer Jim Keltner, is a slow steady march throughout; a snapping backbeat on the snare on two and four and muted high-hat eighth notes are straight above a syncopated bass drum. The toms are restricted to a few, sparse fills. In the first half of the theme, typical of Robertson’s restrained style (although here played by George Doering), the acoustic guitar is almost inaudible and primarily stresses the rhythm: the effect is almost more tactile than sonic. A G-minor chord is strummed with a pick on the downbeat of every other bar beginning in the third measure; a syncopated rhythm similar to, but slightly different from, the bass drum seems to be produced by the thumb tapping on a low string, perhaps with the palm resting lightly on the strings to create a muted, percussive sound.

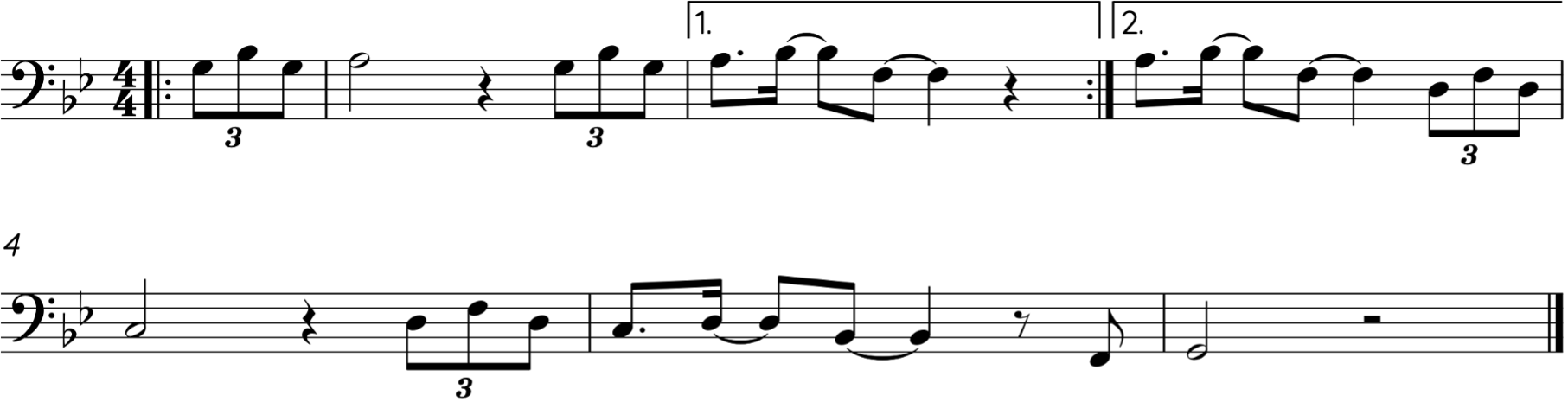

Example 1 shows an abstracted form of the tune, with the spaces between the phrases “normalised” to a downbeat phrase structure. In fact, it is the tension between this implied phrase structure and the steady rhythm section that provides a great deal of the theme’s sense of tension and foreboding, heightened by a complementary melodic/harmonic drive. The simple melody is in G Dorian (minor) mode. There is, strictly speaking, no vertical harmony in the piece, as the pitched instruments carry the melody over the almost subliminal, rhythmicised pedal G from the guitar. Each A and B phrase contains two brief, related phraselets paired in a call-and-response pattern, where the response extends the “call” by tumbling downward. The A section rests heavily on the second of the scale, creating tension between the G pedal and the note above before dropping to the ♭7 of the scale, the note below that pulls upward into resolution to the final.

Figure 5: Conventionalised melody of “The Theme from The Irishman.”

Robbie Robertson, Masterworks, 2019.

Despite the minimal harmonic content, the melodic profile sketches out the chords of a blues progression, with the B section centred on the fifth, dropping down to the fourth, and conceptually, at least, falling to the final. That repeated harmonic drive intensifies the desire for the return to the G final that is, by degree, evaded, thwarted, deferred, and denied. The theme starts on harmonica, played by French virtuoso Frédéric Yonnet, and the melody is then passed to the bowed double bass of jazz bassist Reggie Hamilton, in alternation. At the immediate, surface level, the soloists vary the iterations by pushing and pulling against the beat, usually scooping up into the first note of a phrase with varying attacks; sometimes the three notes at the end of a phrase sound like steady quarter notes, at others almost a quarter-note triplet, and at still others, the expression is even more rubato or syncopated. At a deeper, more unsettling level, the phrases are in unexpected places in the metre. The anacrusis (pick-up) structure of the first phrase feels like it should lead to the downbeat of the bar, but instead lands on the third beat. As it arrives in the middle of the 7th bar, the downbeat feels either too soon or too late for the typical four-bar blues phrase structure. This is only the beginning of the metric play: over the course of the complete theme, the spaces between melodic iterations vary from three (an unexpected anticipation beats) to an extended deferral of fourteen beats. The metric derangement gradually increases over the 4'35" runtime, and the lack of discernible pattern creates musical anxiety.

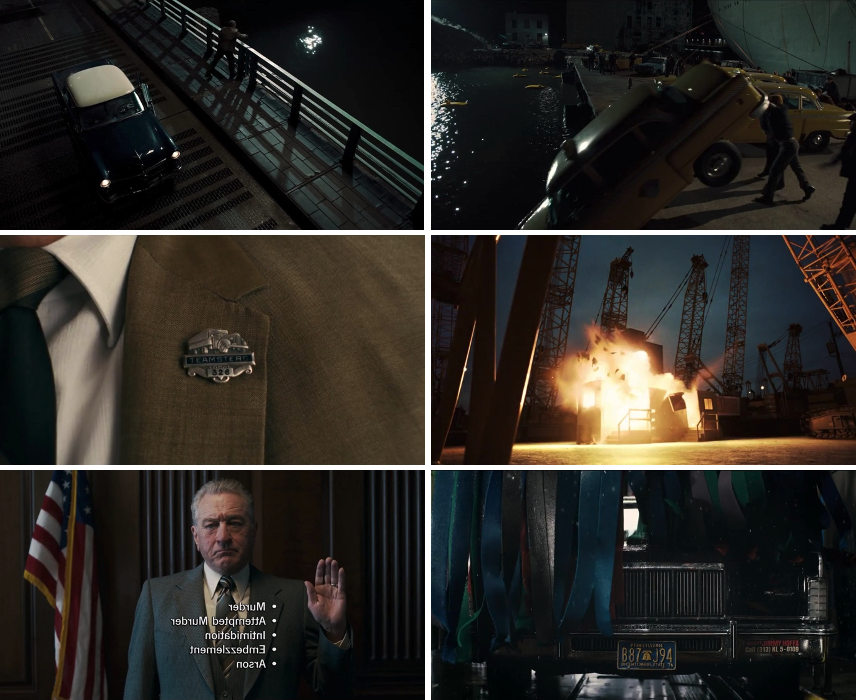

Figures 6–11: “The Theme” traces Frank becoming increasingly enmeshed in the criminal enterprise, from tossing guns used in assassinations off the bridge to his final trial, and the Lincoln car that ends up being a key to the law’s ability to bring him down, underlined by the bass dropping off as the car glides through a car wash. The Irishman, dir. Martin Scorsese. Netflix, 2019. Screenshots.

This disorientation is exacerbated by the evasion of the final and the increasingly visceral timbre of the soloists. The harmonica does not return to the final at all on the first iteration, driving anticipation through to the bass solo’s resolution with a roughly bowed slide from F to G that feels particularly satisfying because of its gruff timbre. With an extended pick-up that echoes the bass’s growling cadence, the harmonica repeats the melody, but this time, shadowed by the guitar, lightly picked with a plectrum to create a clean, crisp echo, to the increasingly smeared and fluttering tone of the harmonica. The guitar’s steady echo amplifies the more exaggerated pushing and pulling of the melody by emphasising the beat’s regularity. When the harmonica reaches the note before the expected cadence, Yonnet spreads the sound and drops the pitch in a deep bend in what sounds like the end of the track. But after six beats of silence, the drums re-enter to accompany the bass, playing with the most variation of phrasing, articulation, and timbre yet. The last phrase sounds almost drunken in its smearing of both rhythm and pitch: instead of closing the cadence with that F-G it had finally delivered on its first iteration (almost as if to prove it could), the bass finishes with an indeterminate slide down to the bowels of the instrument’s range, linked narratively to the law finally catching up with Frank near the film’s end.

The unsettled and unsettling rhythm of the phrasing is particularly effective in this piece because of its stealth. The basic beat is steady, and the phrasing of the melody feels as if it follows traditional four-square patterns—but it most assuredly does not. The timbral qualities are strikingly tactile and even used for musical suspense. The power of the combination of the sensual (haptic) and erotic (unfolding, sequential) is remarkable given the sparse means.

“Remembrance”

Although written in another context, the end-title music “Remembrance” shares significant similarities with the Theme. Both are in (or on) G Dorian, they share an instrumentation, and they both have a bluesy tinge, sharing some basic melodic gestures, most prominently a rubato/triplet-feel anacrusis and a gruff slide up from F to the final G. Despite the track featuring three virtuoso blues-based guitarists, the musicians engage not in the expected cutting contest, but in a three-way conversation that seems to move, at the peak, beyond the exchange of “words” into dance. The elegiac affect is undoubtedly a residue of its original significance as a tribute to a deceased friend. In the film, although we exit the narrative before Frank has died, we see him fragile and elderly in his elder-care home, asking that the door be left open—a symbol of both alertness to and allowing in death.

Figure 12: Frank asks the priest to leave the door open in the last images of The Irishman.

Netflix, 2019. Screenshot.

One can hear in the unwinding of the melodic lines of “Remembrance” some of the building and subsiding of Barber’s “Adagio for Strings”, long a staple of needle-drop film scoring, and Max Richter’s “On the Nature of Daylight”. Robertson had used the latter piece for Shutter Island (Martin Scorsese, 2010) both as underscore[10] and as end credit music in an exquisite mashup with Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth”.[11] In that mashup, Robertson stripped Dinah Washington’s 1960 recording of its accompaniment and laid her vocals into “On the Nature of Daylight”, as he says, “where I would sing it” (Rubin et al.). The combination of surprising “fit” between the two pieces and the subtle but powerful tension between them, even down to micro-rhythms of pronunciation in the singing, is another example of a piece both sensual and erotic, sexy and spooky, propelled and yet haunted by the mismatch of styles.A similar, if somewhat less culturally loaded friction occurs in “Remembrance”, which adds three electric guitarists to the combo of Yonnet, Hamilton, Keltner, Doering, and Randy Kerber on synthesiser, providing rich, fuzzy, but eerily hollow timbres. The guitarists were the three favourites of the memorialised Paul Allen and are of different generations and styles. Derek Trucks (b. 1979) is a slide guitarist with a smooth, glassy portamento; Doyle Bramhall II (b. 1968) is a classic electric blues player, with a dexterous, “clean” attack; and here, Robertson (1943–2023) uses his bare fingers with a sound that emphasises a sighing cry through a combination of melodic profile, bends, and volume swells. Like the “Theme”, “Remembrance” has an AAB structure, this time over a descending minor tetrachord, long a trope of lament.

Figure 13: Framework melody of “Remembrance”. Robbie Robertson, UME Direct, 2019.

The introduction is a rubato synth melody, with interjections from the harmonica, which takes up a free iteration of the melody as the synth initiates the descending tetrachord. With the second iteration of the tetrachord, Trucks enters with a turn figure around the final and a slow improvisation around a rising G-minor triad and, on the third, Bramhall echoes with a figuration both more explicitly triadic and a little more ornate. On the fourth iteration, Robertson takes the subdominant third phrase and intensifies its sighing quality with swells and bends on the first note of each downward gesture. Thus, each guitarist has a variation on a phrase, as if introducing his sound to the listener.

Trucks winds his pure, bright tone around Robertson’s crying sighs as they come together at the end of the phrase. A bass/synth melody gives a moment of contemplation before the harmonica re-enters with a fairly straightforward performance of the melody, decorated by Trucks, heterophonically accompanied by Bramhall, then underscored by Robertson in successive phrases. As Yonnet repeats the B phrase, all three guitars join in with characteristic melodic fragments. They each lament, separately but together, like mourners at a graveside. The return of the bass/synth and harmonica interlude heralds the entrance of the drums in a steady, funereal march into the contrapuntal peak of the piece. The guitars stretch out from their thus-far restrained soloing into more extended phrasing, improvising around each other. Their interactions pass beyond conversation, into something more akin to a dance, long lines twining around each other in variations on the melody as they rise ecstatically to a climax that seems to crest and evaporate, with varying vibrato coming from slide (Trucks), fingerboard (Bramhall), and whammy bar (Robertson). The punctuating bass phrase reappears to close with the harmonica in a soft echo of the beginning, a feeling of coming to rest. “Remembrance” is a balance of touch—the rich, contrasting timbres in an open, transparent texture, particularly the sounds of three electric guitars, each so distinct until they blend together at the peak—and feel, in the inexorable pull forward, melodically and rhythmically. The haptic pleasure in each moment is expanded and extended into the dance at the climax—an exhilarating swirl of the sounds together—and the diaphanous dissolution, short bursts of timbre and melody in the texture like embers breaking in a fire and releasing the last sparks.

Although one of the prime rules of the Internet is “don’t read the comments”, for once the YouTube comments to the posting of the end credit sequence are instructive. The compelling nature of “Remembrance” comes up over and over, both its ability to rivet the listener in place—something particularly notable when the film is being experienced at home rather than in a theatre, as was the case in The Irishman, released by Netflix near the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic—and its instilling of an irresistible desire to hear the music again. One comment in particular captures the pleasure of the structure as well as the sounds:

Micah Rollins: This not the type of song/instrumental that you can just go back to a certain point to hear a specific sound no. You gotta listen to it let it take you away then repeat but this time let take you away far to a land that only you believe in and can see, then repeat again then BOOM [explosion emoji] REPEAT, REPEAT, REPEAT. Robbie told a Story without words on this one yet alone the movie itself.[sic]

In Memoriam

At the Music and the Moving Image conference in 2021, only a few weeks after Danijela’s death, Elsie Walker presented “Listening for Greater Heart Intelligence: Sound Tracks for Embodied Hope”, both a memorial and an examination of her own response to her best friend’s death in a manner that made the most sense to both of them—in the musical cinematic experience. Her paper took the work of Sylvie Droit-Volet and Sandrine Gil on the effect of emotions on our perceptions of time and combined it with techniques from Doc Childre and Howard Martin in The Heartmath Solution. Childre and Martin posit a “level of consciousness that is separate from the brain and that affects every part of us on a cellular level,” and propose a technique by which we may access that “heart intelligence” (65). They call their technique “freeze-frame” (significantly, a term adopted from cinema), although it strikes me as more akin to a time dilation, a conscious slowing down to consider an emotion (66). This, to me, correlates to an important function of music and emotion in storytelling: fans, and even scholars, of musicals often talk about musical numbers as an “interruption” in a narrative, whereas I have felt that, in most instances, they open a bubble in time where an emotion is more fully explored—nowhere is this more obvious than the way the title number in Singin’ in the Rain (Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, 1952) lets us experience Don Lockwood’s joy.

Elsie’s choice of the final scene from Call Me By Your Name (Luca Guadagnino, 2018) illustrates how music both focuses and narrates a process of grieving, of recognising the loss, of remembering the positive in “embodied detail”, of balancing that with the feeling of grief, and then of opening the heart to going on.[12] Sufjan Stevens’s “Visions of Gideon” gives the audience a point of both focus and trajectory as the camera focuses on Elio (Timothée Chalamet), reflecting on his loss, slowing his breathing, and smiling slightly as memories of good times with his lover fleetingly converge with lyrics in the song, until he is able to look out at the audience, ready to go on. The visual concentration on Chalamet’s changing expressions and the song’s gentle guidance to remembering earlier moments of the relationship with him foster empathy in the audience.[13] The control of breathing is an important element of both the practice of this technique and of the narrativising of the experience of grieving into the long exhalation of an emotional resolution.

Grief is not the end of a relationship; that continues on in the emotions and memory of the subject. Music can reflect that experience, and in its ability to mould time, help model the moment of transition from grieving to acceptance, or at least continuance.[14] During Elsie’s presentation, “Remembrance” came immediately to my mind, as her description of the process of grief, contemplation, and resolution seemed engraved in the composition, despite its improvisatory surface. The compellingly sensual timbres and the restrained erotic tension of the structure joined together, fusing it for me indelibly with my remembrance of Danijela.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the editors of Alphaville for the opportunity to express my gratitude to Danijela for her impact on my intellectual life; Elsie Walker for many conversations on these topics; the reader for the journal and Katie Reed for their feedback; and Jolie Ouyang for editorial assistance. I would also like to acknowledge the passing of the composer Robbie Robertson between the original draft and the revision, adding a particular poignancy to this act of “Remembrance”.

Notes

[1] Strikingly, my original draft of this essay started with the exploration of time, as did Elsie Walker’s memorial presentation for Danijela at Music and the Moving Image Conference (2021). I did not have access to that paper at the time of drafting, so either it was in some dark recess of memory, or the similarity of experience fostered a similar approach.

[2] Among her influences in this regard, Danijela lists Susan Sontag, Audre Lorde, Vivian Sobchack, and Laura Marks (9).

[3] In addition to her dissertation, Sound Kinks, her paper on Secretary (Steven Shainberg, 2003) at an earlier Music and the Moving Image conference first re-focused my attention to “haptic” as a sonic attribute.

[4] Coincidentally, but remarkably so, these two films were also significant for Robertson. The Band’s song “The Weight”, written by Robertson, is the music for one of the iconic scenes from Easy Rider, as the bikers wind their way through a Southwestern landscape at sunset. Antonioni had then approached The Band to score Zabriskie Point. As a self-confessed “movie bug”, Robertson was thrilled at the idea of the collaboration, which was not as eagerly greeted by his bandmates and came to naught. Nonetheless, it was the beginning of a long-standing friendship between Robertson and Antonioni (Robertson, Testimony 500).

[5] In his impressionistic photo-essay/memorial to Robertson, Scorsese recalls them listening to cicadas from different seasons from all over Japan (“Martin Scorsese’s Stunning Tribute”).

[6] Spooky and sexy are not opposites. Both produce shivers, pleasures and shocks and represent an array of sensations and experiences placed along several different continua: like many Robertson songs, “Yazoo Street Scandal” is funny, blending witchcraft, horniness, and the relief of rain after a long drought—until it becomes a flood; “Walk in Beauty Way” is a seduction, but is also a haunting or a possession, an invitation to join the lover in their bed—or, possibly, it is their grave.

[7] See, for instance, Bob Ankosko: “I pulled up the Tidal app on my phone and played ‘Somewhere Down the Crazy River’ from Robbie Robertson’s 1987 self-titled solo album in HiFi (CD) quality. It’s a fantastic recording. The Fives projected a cavernous soundstage—the perfect backdrop for Robertson’s deep, mysterious voice, Tony Levin’s melodic bass lines, and those sparse drums thwacks. Everything was clear, distinct… and appropriately eerie.”

[8] Although he neither read nor wrote standard musical notation, Robertson clearly had a keen ear, as producer John Simon has testified, often comparing him to Duke Ellington. Robertson’s ear was undoubtedly nourished by his wide-ranging musical tastes. By the early 1970s, at the height of The Band’s popularity, his fascination with contemporary art music would lead to an epistolary relationship with Krzysztof Penderecki; at the same time, he was collaborating with New Orleans songwriting and arranging legend Allen Toussaint. While he worked with different musicians over the years, some of whom are credited with string arrangements on both film cues and instrumental works on his solo albums, a consistent trait is the careful building of extended tension through voice-leading. Whether it is a product of Robertson working with a collaborator to achieve what he wants or his editing of the recording until the music satisfies his desires, these reflect a consistent compositional voice.

[9] Among Robertson’s patrols are “Night Parade” from Storyville (1991), “Ancestor Song” from Music for The Native Americans (1994), “The Sound Is Fading” from Contact from the Underworld of Redboy (1998), “Reflection (Adagio)” from the film Ladder 49 and “Dry Your Eyes”, a co-write with Neil Diamond from the Robertson-produced Beautiful Noise (1976).

[10] The piece was first used cinematically in Stranger Than Fiction (Mark Forster, 2006), although it is there almost imperceptible. After its use in Shutter Island,“On the Nature of Daylight” was used in nearly two dozen films (most prominently, Arrival (Denis Villeneuve, 2016)), documentaries, television episodes and short films, to the point blogger Danielle Rae Childs pleaded for it to stop!

[11] This mash-up has developed an independent life itself, significantly used to underscore the climactic sequence of The Connection (La French, CédricJimenez, 2014), as a ballet by Christopher Wheeldon, and even as a soundalike composition, “This Bitter Land” for The Land (Steven Jr. Caple, 2016) by Erykah Badu and Nas.

[12] It is impossible not to notice the correlation here with the (in)famous love theme from Titanic (James Cameron, 1997) in which Will Jennings’s lyrics trace a similar trajectory, couched in conventions of romantic song.

[13] Childre and Martin notably use a quasi-musical metaphor—the way a number of metronomes in proximity will eventually synchronise—for this empathetic entrainment.

[14] I remember, as a pre-teen musician, recognising in the shape of Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings” a similarity to the experience of a hard cry: reaching a peak, then the sobs very slowly subsiding into long, shuddering breaths. Later, the piece began to be used in films— notably Platoon (Oliver Stone, 1986)—in ways that seemed to call for that experience of grieving and loss. “On the Nature of Daylight” has a similar shape, as does Robertson’s “Reflection (Adagio).”

References

1. Ankosko, Bob. “Klipsch The Fives Powered Speaker System Review.” Sound & Vision, 23 July 2020. www.soundandvision.com/content/klipsch-fives-powered-speaker-system-review.

2. Antonioni, Michelangelo, director. Zabriskie Point. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1970.

3. Barber, Samuel. “Adagio for Strings, Op.11.” G. Schirmer, Inc., 1936.

4. Barthes, Roland. S/Z. Éditions du Seuil, 1970.

5. Bowman, Rob. “To Kingdom Come (liner notes).” To Kingdom Come: The Definitive Collection. The Band. Capitol, 1989.

6. Cameron, James, director. Titanic. 20th Century Studios/Paramount, 1997.

7. Campion, Jane, director. The Piano. Miramax, 1992.

8. Caple, Steven Jr., director. The Land. IFC Films, 2016.

9. Childre, Doc, and Howard Martin. The HeartMath Solution: The Institute of HeartMath’s Revolutionary Program for Engaging the Power of the Heart’s Intelligence. HarperCollins, 2011.

10. Childs, Danielle Rae. “Stop Using Max Richter’s ‘On The Nature of Daylight’ in Everything.” Cherwell, 27 Apr. 2020. www.cherwell.org/2020/04/27/stop-using-max-richters-on-the-nature-of-daylight-in-everything.11. Chion, Michel. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. Translated by Claudia Gorbman, Columbia UP, 1994.

12. Cocks, Jay. “The Half-Breed Rides Again: Robbie Robertson returns—at last—with a new Record.” Time Magazine, 30 Nov. 1987. content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,966060,00.html.

13. Corio, Paul. “Review of Robbie Robertson: Music For The Native Americans.” Rolling Stone, 2 Feb. 1998. www.web.archive.org/web/20071002100256/http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/robbierobertson/albums/album/116346/review/5946824/music_for_the_native_americans.

14. Daldry, Stephen, director. The Hours. Paramount, 2002.

15. DeRiso, Nick. “Across the Great Divide: The Band, ‘Yazoo Street Scandal’ from The Basement Tapes (1968).” Something Else!, 30 May 2013, www.somethingelsereviews.com/2013/05/30/across-the-great-divide-the-band-yazoo-street-scandal-from-the-basement-tapes-1968.

16. Diamond, Neil. Beautiful Noise. Columbia, 1976.

17. Diamond, Neil, and Robbie Robertson. “Dry Your Eyes.” Beautiful Noise, performed by Neil Diamond. Columbia, 1976.

18. Droit-Volet, Sylvie, and Sandrine Gil. “The Time–Emotion Paradox.” Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society, vol. 364, no. 1525, 2009, pp. 1943–53. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0013.

19. Fink, Robert Wallace. Repeating Ourselves: American Minimal Music as Cultural Practice. U of California P, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520938946.

20. Forster, Mark, director. Stranger Than Fiction. Columbia, 2006.

21. Forte, Dan. “The Many Sides of Robbie Robertson.” Vintage Guitar, Sept. 2011. www.vintageguitar.com/11786/rockin-robbie-robertson. Accessed 2 Oct. 2022.

22. Gorbman, Claudia. “Music and Character.” Keynote Lecture presented at the 4th Music and Media Study Group Conference, Università di Torino, Italy, 28–29 June 2012.

23. ——. Unheard Melodies: Narrative Film Music. BFI, 1987.

24. Guadagnino, Luca, director. Call Me by Your Name. Sony, 2017.

25. Haas, Philip, director. Angels and Insects. Film 4 Productions/The Samuel Goldwyn Company, 1995.

26. Hopper, Dennis, director. Easy Rider. Columbia Pictures, 1969.

27. Horowitz, Hal. “Robbie Robertson: Sinematic.” American Songwriter, 2019. www.americansongwriter.com/robbie-robertson-sinematic. Accessed 11 Sept. 2022.

28. Howell, Peter. “Martin Scorsese’s New Drama Silence ‘So Different from Anything He’s Done’ Says Old Pal Robbie Robertson,” Toronto Star, 24 Nov. 2016. www.thestar.com/entertainment/movies/2016/11/24/martin-scorseses-new-drama-silence-so-different-from-anything-hes-done-says-old-pal-robbie-robertson.html.

29. Jaffe, Ira. Slow Movies: Countering the Cinema of Action. Columbia UP, 2014. https://doi.org/10.7312/jaff16978.

30. Jagger, Mick, and Keith Richards. “Jumping Jack Flash.” Jumpin’ Jack Flash/Child of the Moon, performed by The Rolling Stones.Decca/London, 1968.

31. Jimenez, Cédric, director and writer. The Connection [La French]. Gaumont, 2014.

32. Kelly, Gene, and Stanley Donen, directors. Singin’ in the Rain. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1952.

33. Kluge, Kathryn, and Kim Kluge. Silence: Original Music Soundtrack. Rhino Warner Classics, 2017.

34. Kreisberg, Jennifer, and Pura Crescioni. “Ancestor Song.” Music for The Native Americans, performed by Robbie Robertson and the Red Road Ensemble. Capitol, 1994.

35. Kulezic-Wilson, Danijela. Sound Design Is the New Score: Theory, Aesthetics, and Erotics of the Integrated Soundtrack. Oxford UP, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190855314.001.0001.

36. Levine, Robert. “Robbie Robertson on His Memoir & Why He’s ‘Not Interested in Oldchella’”, Billboard. 18 Nov. 2016. www.billboard.com/music/features/robbie-robertson-memoir-testimony-the-band-7581157.

37. Mahler, Gustav. Symphony No. 1. Weinsberg, 1898.

38. McClary, Susan. “Getting Down Off the Beanstalk: The Presence of a Woman’s Voice in Janika Vandervelde’s Genesis II.” Minnesota Composers Forum Newsletter, Jan. 1987, pp. 4–8.

39. ——. “Minima Romantica.” Beyond the Soundtrack: Representing Music in Cinema, edited by Daniel Goldmark et al. U of California P, 2007, pp. 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520940550-005.

40. ——. “Terminal Prestige: The Case of Avant-garde Music Composition.” Cultural Critique, vol. 12, Spring 1989, pp. 57–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/1354322.

41. Nas and Erykah Badu. “This Bitter Land.” The Land (Music from the Motion Picture). Mass Appeal, 2016.

42. Pääkkölä, Anna-Elena. Sound Kinks: Sadomasochistic Erotica in Audiovisual Music Performances. 2016, University of Turku, PhD Dissertation. Annales Universitatis Turkuensis, urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-29-6608-0.

43. Richter, Max. “On the Nature of Daylight.” The Blue Notebooks. 130701, 2004.

44. Robertson, Robbie (Jaime Robertson). Contact from the Underworld of Redboy. Capitol/EMI, 1998.

45. ——. Music for The Native Americans. Capitol, 1994.

46. ——. “Night Parade.” Storyville. Geffen, 1991.

47. ——. “Reflection-Adagio.” Ladder 49 (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack). Hollywood Records, 2004.

48. ——. “Remembrance.” Sinematic. UME Direct, 2019.

49. ——. “Remembrance.” The Irishman, directed by Martin Scorsese. Netflix, 2019.

50. ——. Robbie Robertson. Geffen, 1987.

51. ——. Sinematic. UME Direct, 2019.

52. ——. “The Sound is Fading.” Contact from the Underworld of Redboy. Capitol/EMI, 1998.

53. ——. Storyville. Geffen, 1991.

54. ——. Testimony. Crown Archetype eBook, 2016.

55. ——. “Theme for The Irishman.” The Irishman, directed by Martin Scorsese. Netflix, 2019.

56. ——. “Theme for The Irishman.” The Irishman (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack). Masterworks, 2019.

57. ——. “To Kingdom Come.” Music from Big Pink,performed by The Band. Capitol, 1968.

58. ——. “Unbound.” Contact from the Underworld of Redboy.Universal, 1998.

59. ——. “Unfaithful Servant.” The Band, performed by The Band. Capitol, 1969.

60. ——. “Walk in Beauty Way.” Sinematic. UME Direct, 2019.

61. ——. “The Weight.” Music from Big Pink, performed by The Band. Capitol, 1968.

62. ——. “Yazoo Street Scandal.” The Basement Tapes, performed by Bob Dylan and The Band. Columbia, 1975.

63. Robbie Robertson and the Red Road Ensemble. Music for The Native Americans. Capitol, 1994.

64. Rollins, Micah (Comment 15 Sept. 2021), “Robbie Robertson - Remembrance | The Irishman OST”. www.youtube.com/watch?v=NBHLsJPGAVU. Accessed 24 Sept. 2024.

65. Rubin, Rick, et al., hosts. “Robbie Robertson: Leader of The Band and Architect of Shangri-La.” Broken Record Podcast, 11 Feb. 2020. Puskin, www.pushkin.fm/podcasts/broken-record/robbie-robertson-leader-of-the-band-and-architect-of-shangri-la.

66. Russell, Jay, director. Ladder 49.Touchstone, 2004.67. Scorsese, Martin, director. Casino. Universal, 1995.

68. ——, director. The Irishman. Netflix, 2019.

69. ——, director. The Last Waltz. United Artists, 1978.

70. ——. “Martin Scorsese’s Stunning Tribute to His Late Friend Robbie Robertson.” Rolling Stone, 17 Sept. 2023, www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/martin-scorsese-remembers-robbie-robertson-collaborations-friendship-1234820757.

71. ——, director. Mean Streets. Warner Brothers, 1973.

72. ——, director. Raging Bull.Chartoff-Winker Production, 1980.

73. ——, director. Shutter Island. Paramount/DreamWorks, 2010.

74. ——, director. Silence. Paramount, 2016.

75. ——, director. The Wolf of Wall Street. Paramount, 2013.

76. Shainberg, Steven, director. Secretary. Lionsgate, 2002.

77. Simon, John. Truth, Lies & Hearsay: A Memoir of a Musical Life in and Out of Rock and Roll. John Simon, 2018.

78. Stevens, Sufjan. “Visions of Gideon.” Call Me by Your Name: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack. BMG Gold Songs, 2018.

79. Stilwell, Robynn J. “The Fantastical Gap between Diegetic and Nondiegetic.” Beyond the Soundtrack: Representing Music in Cinema, edited by Daniel Goldmark et al., U of California P, 2007, pp. 184–202. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520940550-013.

80. Stone, Oliver, director. Platoon, 1986.

81. Tarkovsky, Andrey. Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema. Translated by Kitty Hunter-Blair, U of Texas P, 1989.

82. Villeneuve, Denis, director. Arrival.Paramount, 2016.

83. Walker, Elsie. “Listening for Greater Heart Intelligence: Sound Tracks for Embodied Hope.” Music and the Moving Image XVII, NYU Steinhardt, USA, 30 May 2021, online.

84. Washington, Dinah. “This Bitter Earth.” Unforgettable. Mercury Records, 1960.

85. Wheeldon, Christopher, choreographer. “This Bitter Earth.” Five Movements, Three Repeats, Vail International Dance Festival,Gerald R. Ford Amphitheater, Vail, Colorado, Aug. 2012.

86. Wheeler, Brad. “Robbie Robertson Was the Chief Craftsman behind The Band’s Music.” The Globe and Mail, 10 Aug. 2023, www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-robbie-robertson-music-legacy.

87. Willman, Chris. “Review of Storyville by Robbie Robertson.” Los Angeles Times, 29 Sept. 1991, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-09-29-ca-4489-story.html.

Suggested Citation

Stilwell, Robynn. “‘Remembrance’:Reticence, the Sensual, the Erotic, and the Music for The Irishman.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 27, 2024, pp. 169–188. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.27.15

Robynn Stilwell (Associate Professor of Music) teaches in the music, dance, writing, and film and media studies programs at Georgetown University. As a musicologist, her research interests center on music as cultural work, and music as an expression, or impression, of movement and space. Publications include essays on Beethoven and cinematic violence, affective space in the films of Baz Luhrmann, musical form in Jane Austen, rockabilly and “white trash,” figure skating, French film musicals, psychoanalytic film theory and female subjects, and the boundaries between sound and music in the cinematic soundscape. Current projects include a historical study of audiovisual modality in television; and an exploration of sound and music in aural media (radio, podcasts, audiobooks).