“He Has Music in Him”: Musical Moments, Dance and Corporeality in Joker (2019)

Jessica Shine

[PDF]

Abstract

Danijela Kulezic-Wilson has discussed at length how the use of music in cinema adds to its corporeality and both fleshes out and gives life to otherwise spectral images. Todd Philips’ Joker (2019) both narratively and aesthetically leverages music to embody Arthur Fleck’s (Joaquin Pheonix) transformation from outcast to popular villain. In a Q&A with The Academy, Philips described the character of Fleck as full of grace and someone who “has music in him”, and it is Fleck’s performative interaction with the music as he becomes the Joker that leads to the corporeal reading of the film presented in this article. At the beginning of the film, Fleck is a thin and gaunt man, a ghostly figure lacking love or meaning, but he soon grows more bold and violent. Fleck’s horrifying acts of violence are accompanied by his bodily interaction with the music as he dances to both the soundtrack and the score as if it were emanating from him in some meta-diegetic sense. Joker is a deeply musical film, and its protagonist engages with both Hildur Guðnadóttir’s composed score and its compilation soundtrack, giving physical form to his metamorphosis. This paper investigates how musical moments and dance in Joker give corporeal form to Fleck’s alter ego and simultaneously encourage audience identification with its protagonist’s transformation.

Article

Directed by Todd Philips, Joker (2019) generated controversy before it was even released. Set in the DC comic-book universe, the film was an original repositioning of the Joker’s origin story that significantly deviated from the DC universe canon. Superfans of the franchise clamoured to boost its credentials and ensure the film had a score of 9.4 out of ten on IMDB prior to its release. Criticism of the film was often met with frightening backlash on the Internet (Zacharek). An orchestrated cohort of fans spammed film critics with death threats and Internet fora were buzzing with fearful chatter about possible cinema shootings during the screenings (Wilkinson). In the wake of the mass shooting in 2012 in Aurora during a screening of The Dark Knight Rises (Christopher Nolan, 2012), a film set in the same comic-book universe as Joker, these online threats caused genuine concern (Margolin and Katersky; McPhate). However, as William Chavez and Luke McCracken note, there is little evidence that the Aurora shooter identified with the Joker in Nolan’s film, and it was cinema theatres themselves that were the target (17). The authors argue that the hysteria around Joker was rather driven by media outlets (17). Nonetheless, the Aurora cinema did not screen the film (Harris).

The online targeting of critics echoed previous online campaigns that aimed at critics of Suicide Squad (David Ayer, 2016). As with Joker, fans had flooded IMDB’s review section with a host of hyper-positive comments and any critics who gave less than stellar reviews faced a tirade of abuse from enraged fans, who even campaigned to have review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes shut down (Johnson; Child). Joker became, like many other comic-book films, a focal point for the newly emerging fan phenomenon of the toxic fandom. Suzanne Scott argues that toxic fandoms are bound up in performative acts of trolling online and that there is an overlap between certain online groups of fans and online groups of Internet trolls.[1] Joker’s repositioning of Joker as outcast-become-hero was indeed seen by many critics as deliberately pandering to the darker cohorts of online comic-book fandoms.

While much of the toxic-fan backlash against other releases of comic-book, fantasy or sci-fi films centred around those films’ attempts to diversify casts in terms of race, gender or sexuality (C. Williams; Johnson; Hanna), Philips’s film centres itself not only around a white male character, but a downtrodden victimised “loser”. Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix) lives with his mother, struggles with his finances and his mental health, and cannot find love or friendship in the diegesis’ cruel world. Writing for IndieWire, David Ehrlich states that Joker is a “toxic rallying cry for incels”, and his colleague Ryan Lattanzio echoed his sentiments writing that “Phillips’ film apparently lacks the nuance or sensitivity required of such a project in an age of rampant Reddit.”[2] Philips’s directorial decisions were viewed by many critics as a cynical indulgence of these online fanbases. Chavez and McKraken argue that Philips’s reimagining of Joker as “depressingly ordinary” instead of a criminal mastermind made the character more relatable to similarly disaffected audience members, and that subsequently fed into the fear surrounding potential copycat crimes. For Chavez and McKraken,

this reinterpretation of the character inspires audiences both to empathize with his mundane plight and to fear his radicalization as representative of a dormant social reality. Accordingly, audiences began to fear the film itself—the empathy it generates—as a potential catalyst for radicalizing certain viewers and inciting offscreen violence. (5)

In their article, the authors also note how the diegetic construction of Arthur Fleck made him appealing to certain Internet subcultures, particularly incels. This type of indulgence of fandoms, Scott argues, is part of a broader pattern of films deliberately antagonising fans or, conversely, offering them “fan proxy characters” (143). Scott’s arguments also echo Derek Johnson’s discussion of the reciprocity between fan and studio and its impact on the content of new projects. Whether intentional or not, the iteration of the Joker presented in Philips’s film encouraged a high degree of affinity between cohorts of online fans and the titular character. The notion that audience members would extend their empathy with Fleck to emulating his violence was taken seriously enough that Landmark Theatres banned all costumes from their screenings and though AMC allowed patrons to wear costumes, they banned the use of face paint or masks, effectively banning the Joker costume (Bankhurst).

Given the overall cultural context of the toxic-fandom, it is arguably surprising that there have to date been no specific acts of violence linked to the release of the film. However, Phoenix’s Joker has resonated with fans across myriad Internet platforms; this empathy with the character has manifested itself in various forms such as memes, avatars, videoed dances, GIFs, etc. This article examines the role dance plays in promoting this empathetic response in the viewer and contends that, by having the Joker actualise himself through dance rather than through violence, suggests that acts of violence were the end result of the character’s metamorphosis and not the cause of it. As I will argue, Phoenix’s use of dance to manifest the character of Joker emulates other iterations of the Joker, specifically Jack Nicholson’s imagining of the character as a villain who waltzed and tangoed his way around destruction in Batman (Tim Burton, 1989); however, the dancing in Joker is less about exuberant villainy and more about metamorphosis and becoming. Where Nicholson’s Joker was assured and confident from the outset of that film, it takes Arthur Fleck the duration of the narrative to embrace his own bodily expressivity. Fleck’s confidence is slowly found through a series of iterative dances that are accompanied by both the score and the compilation soundtrack. Accordingly, this article contends that the film’s musical moments give corporeal form to the spectral figure of the Joker and that the way in which dance and music are used to actualise the Joker promotes an empathetic response in the viewer to the character’s metamorphosis. The article explores how the embodiment of musical moments through dance fosters potential empathy by prompting a haptic and tactile response to the film and, by extension, its titular character. It further explores how the film’s musical moments eroticise Fleck’s body to such an extent as to encourage identification with both Fleck and his process of becoming Joker, contextualising and problematising this empathic response within a broader theoretical framework.

Score as Metamorphosis

Hildur Gudnadóttir’s score was well received by critics, and she also became the first woman to win an Academy Award for original score. Her score is thoughtfully used in Joker, transitioning between diegetic and meta-diegetic, becoming something of a character itself as it accompanies many of the film’s dance scenes. Music and dance have a symbiotic relationship in the film, and both are used as powerful, intertwined narrative devices. Though Gudnadóttir’s score is apparently nondiegetic, its presence seems to haunt the dance scenes, like a ghost moaning as it physically possesses Arthur’s body. Her music also haunted the set of the film itself, with the score being played to the crew, particularly Phoenix, during the filming process: “We would use that score on the set of the movie. I had it playing in my headphones, the camera operator had it playing in his headphones, Joaquin would be hearing it. The sound guys wanted to kill me, but we’d be playing it over speakers during scenes. It really infected the set, in a good way, and it was just sort of in everybody’s bones” (Philips qtd. in Greiving). Like the score, dance was also crucial to the world of Philips’s film, in particular its main protagonist, and its role in Fleck’s metamorphosis into Joker was widely discussed by film critics. Writing for the LA Times, Tim Greiving states that “Joker comes alive through dance in several places in the script.” These moments often correspond to penetrative instances of Gudnadóttir’s score. The importance of dance in the film is also noted by Eric Eisenberg, who writes that “Arthur Fleck is a guy who dances as a method of outward expression of his thoughts and feelings, which is significant given that he bottles so much of himself up when out in regular society.” For Gia Kourlas, then, “Dance is Arthur’s escape, his life force.” Fleck’s transformation into the Joker is first realised through dance rather than acts of violence, his first act of violence being an act of self-defence, as I will outline below.

Arthur’s acts of violence are justified within the film’s diegesis as reactions to the inhumanity of the world around him, which he believes has treated him terribly. The film frames Arthur’s perception of the injustices he faces as accurate, though we later learn that his perception of the world is severely influenced by fantasy and hallucination and that he is a very unreliable narrator. Arthur’s violent actions become, within the diegesis of the film, the inspiration for others to also act violently. Each act of violence, whether committed by Arthur or by copycats, breathes more life into the spectral figure of Joker, who becomes more and more physically apparent in Arthur’s movements, particularly in his dance, as if the Joker has become puppet master over Fleck’s body.

Though dance becomes the medium of expression for Joker, the first time we see Arthur dancing in the film is painfully awkward, the opposite of the confidence he displays in interacting with music later in the film. The first dance scene takes place in Arthur’s sitting room. In the preceding scenes, Arthur is savagely beaten by hooligans on the street while he is working. After this incident, his colleague Randall (Glenn Fleshler) gives him a gun for self-defence. Due to his mental-health issues (which are particularly ill-defined within the film) Arthur is not permitted to have a firearm; however, he eventually accepts the gun.[3] He is later seen sitting on his couch, shirtless and watching television. Fred Astaire and Dudley Dickerson’s rendition of “Slap that Bass” emanates from the TV set, and Arthur dances irrhythmically with his hands above his head, clutching the gun. He begins a hallucinated conversation with an imagined woman during which she compliments his dancing. The camera frames him from deliberately awkward angles: a close-up shot under his face that highlights every crease and furrow, a medium shot of his bony torso that emphasises his physical frailty. His pretend dialogue is forced, and he points the gun at another imagined character, whom he claims is a bad dancer. The gun accidentally fires, catching Arthur by surprise, and he falls unceremoniously to the ground, humiliated in front of the imaginary woman whom he was attempting to woo. In this scene, Arthur is presented as frail and socially awkward, though he clearly desires to be much more than what he is. Though he is prompted by the rhythms of Astaire’s song to get up and dance, this music does not awaken the Joker within him, nor does the dancing allow him to shed his awkwardness. Arthur returns to work the next day and brings the gun with him to a children’s hospital where his goofy dancing for the patients causes the gun to fall on the floor. As a result, Arthur is fired from his job.

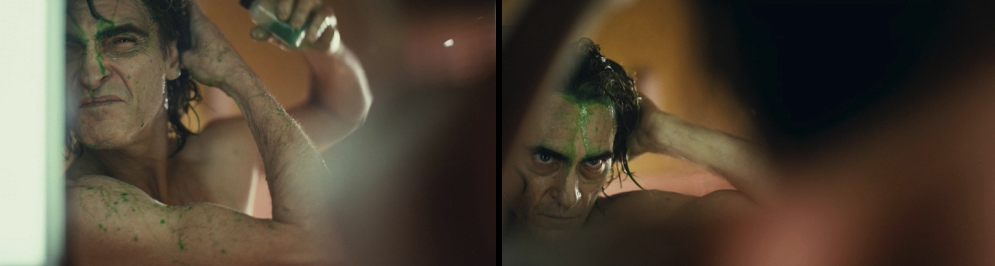

After being fired Arthur takes the subway home, still dressed as a clown. During the ride three businessmen harass a young lady. She appeals to Arthur for help. Arthur instead bursts into the stress-induced hysterical laughter caused by his illness. The three men then decide to target Arthur and one begins a terrible rendition of “Send in the Clowns”. The men begin to beat Arthur; however, he produces the gun and shoots two of the men dead during the fracas. The third man escapes the carriage, but Arthur follows him with determination and purpose and, eventually, catches up to him on the subway stairs and shoots him in the back, which kills him. Arthur then flees the scene and makes his way into the grimy public toilets. As he stares at himself in the bathroom mirror, Gudnadóttir’s score begins in the background, sonically interacting with the sounds of flickering lights and Arthur’s heavy breathing. It is a slow, mournful piece led by cello, the electrification of which adds an eerie, otherworldly quality to the timbre of the piece. Arthur begins to dance slowly, moving one foot in front of the other. From the ground up, he begins to move, tracing his foot delicately across the floor. Slowly, the diegetic sounds, including Arthur’s laboured breathing, fade into the background and the score consumes the sonic space. Then, the rest of his body begins to move. His hands outstretch. His neck cranes. All the time the lights flicker and the grimy bathroom contrasts with the beauty, elegance and simultaneous strangeness of the music and his dance. His dishevelled appearance and messy makeup are incongruent with the grace of his movements, as if two disparate characters inhabited the same body. The camera lingers on Arthur, highlighting the full-bodied nature of his dance, almost caressing his hands, feet, shoulders and torso. Arthur stares at himself in the mirror, arms outstretched, while a deep and strident percussive beat resonates from the score. This metaphor of the mirror becomes important for subsequent dances, as Fleck also sees himself reflected in both mirrors and screens during later dance sequences. We linger on Arthur as he gazes upon himself, and then the shot cuts away to the apartment building as we follow a now-emboldened Arthur as he approaches the apartment of his neighbour. She answers the door and Arthur kisses her forcefully; she reciprocates, the kiss fulfilling the eroticism of the dance scene.

Figures 1–3: Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix) becoming Joker in the bathroom dance scene.

Joker, dir. Phillips Todd. Warner Bros., 2019.

The music–image combination of score and dance in the scene I described works to eroticise Fleck’s body, and that eroticisation encourages empathy, if not adulation in the viewer. Danijela Kulezic-Wilson discusses how music and sound can forge connections between the film viewer and the body of film itself. For Kulezic-Wilson, the films Beau Travail (Claire Denis, 2000)and The Fits (Anna Rose Holmer, 2017)deploy the language of physicality with eloquence and use our fascination with the human body in action to create rhythmical, sensuous film forms that also provide insight into the characters’ suppressed desires and inhibitions, and their process of coming to terms with their individuality. And in the same way as our bodies surpass the limits of nonverbal communication through kinesics, so film uses its own body—image, sound, music, movement, and rhythm—to transform the technical and industrial into the sublime. (Sound Design 116)

Joker uses sound, music and the body of its protagonist to present the emergence of the Joker as something akin to a corporeal possession of Arthur, as if the Joker seized control of his body. This scene, as the camera lingers on Arthur’s body as it interacts with the cello score, presents the moment of the Joker’s first physical manifestation, his transition from spectral haunting to embodied figure. The spectre of the Joker haunts Arthur and is exposed to him and the audience through Gudnadóttir’s score but realised through the gyrating body of Fleck.

Martine Beugnet writes that “cinema as a medium has an ability to merge outer and inner vision as well as evoke inner feelings through images of the world”, and that it is a “medium to experiment with the notion of the human body and its limits, the permeability of outer and inner reality” (Beugnet and Mulvey 190). In Joker, the inner and outer worlds of its protagonist are so permeable that they blur together to such an extent that the viewer is not sure if the whole film even takes place at all. Beugnet further argues that French cinema of the senses “characteristically offer themselves to the spectator as deeply sensuous universes in which the audio-visual medium of film is used to evoke other senses (taste, smell, and, crucially, touch) so that they can be said to encourage a ‘tactile,’ ‘haptic’ gaze and empathetic involvement from the viewer” (Beugnet and Mulvey 191). Philips’s framing of Arthur’s dancing, fragmenting his body, focussing on his gaunt frame, the fading in and out of diegetic sounds, or sounds of Arthur’s bodily movements that occasionally punctuate the score or soundtrack on the beat, all create a sensuous environment and a feeling of closeness to Arthur in his most private moments. They also make tangible the ghostly figure of the Joker himself. In other words, this scene prompts the viewer to respond to Joker’s emergence in a tactile and haptic way, which encourages empathy in the viewer with Arthur’s metamorphosis. Beth Carroll, building on the work of other haptic cinema scholars such as Laura Marks and Jennifer Barker, discusses the importance of movement in creating a tactile experience for the viewer. She writes:

The body thus has the ability to “feel” the film. Movement is important to this as vision is kinaesthetic through its registering of movements of the body. Consequently, as the eye perceives the movement of the images, it is picked up tangibly and tactilely by the body of the spectator; hence the embodied act of spectatorship. Audiences experiencing a film are doubly situated, existing in two places at once without leaving their seats. They are experiencing the world of the film at the same time as experiencing the world of the cinema. (14)

The way the camera moves over Fleck’s body, and the way Fleck’s body moves within the diegetic space all serve to draw the spectator into that moment.

In her discussion of Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s 2015 film The Assassin,Kulezic-Wilson argues that,

[b]y drawing on the sensuousness embodied in the melodies and harmonies of the film’s compositions, textures, and sounds, rhythm becomes the primary vehicle for creating the connection between the body of the audioviewer and that of the film. In this context the artistry of sound is not the result of an elaborate design that dazzles with its inventiveness or is foregrounded for dramaturgical or affective reasons; the purpose of sound is neither to support the image nor to oppose it in order to assert its independence. The focus instead is on forging a delicate interaction between sonic and visual elements to create a distinctly rhythmic audiovisual texture. (Sound Design 123)

In her discussion of The Assassin, Kulezic-Wilson notes that it is only the viewer who is willing to “submit” to the film’s rhythm that is drawn into it. In many ways, though perhaps for different reasons, Philips’s film creates a distinct audiovisual rhythm that is indeed forged by the interaction between the sonic and the visual, particularly between the score/soundtrack and Arthur Fleck’s dancing body. But for Joker, if the viewer submits to the rhythms of Fleck’s dance, the rhythmic caressing of Fleck’s body by the camera and the sensuousness of the score, it creates the difficult conundrum of submitting to a film that centres on a murderer or rejecting the pull of the music/image combination. And it was precisely the former that worried many critics, who feared that those who empathised with Fleck and, by extension, Joker would extend their empathy to mimicry.

In her article “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess” Linda Williams proposes a subgenre of film, a “gross” type of “body genre” which feature, she argues, a “spectacle of a body caught in the grip of intense sensation or emotion” (4). She reminds us that these films deliberately manipulate the viewer, who feels that manipulation in bodily expressions of crying, fear responses or sexual arousal. Building on the work of Williams, Jennifer Barker argues that “viewers’ bodily responses to films might be mimicry in another sense: not mimicry of characters, but of the film itself. Perhaps viewers respond to whole cinematic structures—textural, spatial, or temporal structures, for example—that somehow resonate with their own textural, spatial, and temporal structures” (73). And for Philips’s film dance is crucial to this shift away from mimicking the Joker’s acts of violence, allowing the viewer to empathise with, and respond in a bodily way, not to his violent acts but his metamorphosis through dance and the sensations produced by the relationship between the dancing body and the score.

Isabella van Elferen writes that “[t]elevisual and film music’s spectrality begins with the very notion of non-diegetic music—this is music that is not part of the plot, is not heard by the characters, but only perceivable by the TV or film audience” (291). This is complicated in Joker as the spectral presence of the score symbolically represents a being that has not yet been manifested, something that is simultaneously within Arthur and outside him. It is also unclear whether the music is indeed unheard by the characters, as Arthur’s apparent dance interaction with the score begins to give corporeal form to the ghostly presence of the music. Kevin Donnelly writes in The Spectre of Sound that ghosts inhabiting a film are often “little more than shapes, momentary musical configurations or half-remembered sounds. Music can suggest, or even can lead directly to, an elsewhere, like a footnote” (172). Music bridges the physical gap between body and mind, between audience and character, and gives us sonic access into Arthur’s psyche. Philips states that[o]ne of the things we spoke about was that Arthur had music in him. It existed in him. Some people you may know personally have that feeling. And I always thought that about Arthur, but it was always kept in and trapped. And there was something about that evolving. But the scene in the bathroom […] that’s not in the script. That was just something that evolved, and became a moment to show that [music] fighting to get out. (qtd. in Manalo)

This can be seen in both Phoenix and Gudnadóttir’s discussion of the scene. When Phillips sent footage to Gudnadóttir, she was amazed: “It was magical […] It was completely unreal to see the physical embodiment of that music. His hand gestures were the same types of movements that I felt when I wrote the music. It was one of the strongest collaborative moments I’ve ever experienced” (qtd. in Godfrey). Discussing the same moment, Phoenix states: “He came out through the movement and the dance. So, when we started playing this music—a cello piece—and I came in and started to move… It was very natural. This idea of metamorphosis was intriguing to me. Who is this guy, and how did he become who he is? It was almost some kind of interpretive dance” (qtd. in Smaczylo). The bathroom scene in Joker is consistently discussed by those involved with its making in terms of transformation and change. This scene, rather than the violence that precedes it, is the moment where the Joker as a character appears, as if the ghostly figure of the Joker was merely awoken by the violence but given life through the interaction between body and music and actualised through dance. Alex Godfrey writes that, for this scene, “Phillips and Joaquin Phoenix decided to scrap the beats they had planned and, stuck for inspiration, Phillips played the piece of music Guðnadóttir had written. Phoenix reacted to it, improvising some interpretive dance. He had been struggling to find a way to have Arthur began [sic] to transform into the Joker; this was it.” Philips states that “he just starts dancing, that’s not in the script; that’s not in the thing. That’s just something that kind of evolved like ‘Oh, this is a moment where we can show that it’s kind of fighting to get out’” (qtd. in Eisenberg). In an interview with Indewire, Phoenix describes it as the moment that had to be about the “emergence of Joker” (qtd. in Thompson). His reading of this bathroom dance scene as the “emergence of Joker” is interesting because it takes place after a violent scene, in other words Joker’s emergence is in reaction to the violence rather than during the actual acts of violence.

Music is central to Fleck’s transformation. Kulezic-Wilson discusses the role of music and image in the concepts of flow and morphing. She writes:

these two processes are practically inseparable from each other as the pull of music in many ways results from the fact that its flow embodies a process of change/movement which is generally associated with the experience of listening to music. From the simplest musical forms which might be based on the change of a single musical parameter to complex orchestral textures in which the process of morphing is so palpable in every aspect that it can be experienced on a visual or a spatial level, music brings the sense of transformation of sound in time. Even works which emphasize the idea of stasis and nonlinear temporality utilize the process of morphing on some level, whether rhythmical, harmonic, melodic or timbral. (Musicality 9)

Gudnadóttir’s score noticeably changes in the bathroom scene, progressing from low cello drones and simple fragments of a melody earlier in the film to a fuller hypnotic melody as Arthur dances. The articulation of palpable melody that is given bodily form as it is expressed through Arthur’s graceful deliberate movements gives both voice and body to the music within Arthur, transforming it from something spectral to something tangible. Gudnadóttir recognises the implicit link between her score and the voice of the Joker and its ability to be felt in a tactile way when she states: “I found the notes, and I had such a strong physical reaction. It was like ‘that’s him, that’s his voice’” (qtd. in Burlingame). Through the act of dance, the spectre of the Joker passes from score to body. Eisenberg writes that,

[f]rom that point forward, you’ll notice watching the movie that Arthur primarily dances whenever he is feeling most comfortable in his own skin. At first this is mostly a private thing, as he moves his hips in the living room or swings around his long hair in the mirror, but it’s when this part of his persona becomes more public that things get really, really scary.

While Eisenberg’s assessment is accurate, I wish to extend it a little further and argue that the Joker is not simply a part of Fleck’s persona, but something much more consuming that cannot be compartmentalised. Joker presents Fleck’s transformation from shy mother’s boy to a terrifyingly unpredictable villain as something all consuming, as if he were possessed by a spectre. This is implied in the interaction between Fleck’s bodily movements and the musical score, which transcends its position as nondiegetic and, though it is never given a specific location within the film frame, clearly becomes the instigator and accompaniment for the onscreen dance.

Dancing towards Destruction

Arthur’s murder of the men on the subway inspires copycat acts of violence across Gotham city. Rioters dressed as clowns begin to target the wealthy elite of the city. Meanwhile, Arthur learns that his mother has been lying to him all his life about his father, and that she herself has significant mental health issues. This realisation combined with the fact that his idol, chat show host Murray Franklin (Robert DeNiro), uses video footage of Arthur’s failed stand-up gig as the butt of the joke for his show drives Arthur further towards violence, and Murray Franklin becomes the chief focus of his rage. The process of Arthur’s transformation from downtrodden loser to antihero is presented in a series of musical moments. For the rest of the film, Arthur interacts with both diegetic music and with the score, as if both were located in the same metadiegetic space inside his mind, preparing himself for his now premeditated acts of violent revenge with dance, and revelling in their execution in the same way.

In contrast to the sensuous allure of the score and the soft caress of the camera in the dance scenes the sounds of the violence committed by Fleck fall distinctly into Lisa Coultard’s definition of “acoustic disgust”. In a horrifying scene, Arthur suffocates his mother in the hospital. We can hear his laboured breathing, the sounds of the pillow shuffling as he holds it over her face, her muted pleas and gasps. The scene does not use any of Gudnadottir’s score to diminish the acoustic reality of the murder, something which, as Coulthard notes, is rather rare:

In surveying approximately 100 violent scenes in contemporary film and television, I found that although sound played a key role in the effects and impact of violence the acoustic dominants focused on music or noise, rather than on the act of bodily wounding itself. By far, the most popular current trope is for overwhelming music cues, with some scenes of violence so heavily scored that diegetic sound is eradicated entirely. (184)

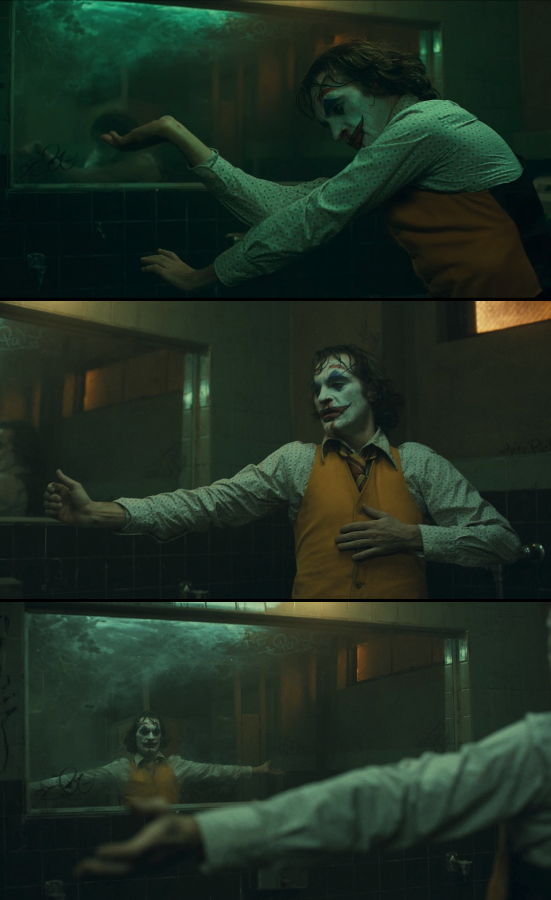

Fleck returns to his apartment and dyes his hair green and dances around his bathroom to “That’s Life”, which is the theme tune for the Murray Show, the show that he once adored but on which he was ruthlessly mocked. In this scene, Arthur displays more confidence and swagger than in previous scenes.[4] The camera frames his almost naked body as he moves freely, unencumbered by his previous awkwardness. His body moves through space with carefree motions, the hair dye spilling down his face. Droplets of dye and water fly through the air as he shakes his head. Occasional diegetic sounds of rustling and squelching interact with the song, adding some bodilyness to the soundtrack. Arthur is now more confident in looking at his reflection and dances to it, interacting with it. His hips thrust and his arms curl, a clearly sexualised act, signifying his confidence and newfound virility. In this scene, dance both acts as his reaction to the murder of his mother, and foreshadows his murder of his former colleague, Randall. We cut to Arthur applying his make up in long deliberate strokes, moving the brush over his lips and then over his tongue. Shortly after this sequence, while Arthur is still half undressed, Randall and Gary (Leigh Gill) arrive. During a conversation where Randall tries to manipulate Arthur into lying to the police about how Arthur got the gun, Arthur brutally murders him, but lets Gary go as Arthur says that he had been a good man to him.

Figures 4 and 5: Fleck dances as he dyes his hair green. Joker. Warner Bros., 2019.

Crucially, the sonic space is different during the murders from the dance scenes. During Randall’s murder, as Fleck draws the knife from his pocket, we hear a momentary glimmer of Gudnadottir’s score. However, as the murder commences, the soundtrack uses no music, punctuated only by the squelching sounds of the blade, Gary’s horrified cries as he witnesses the murder, the thudding of Randall’s skull against the wall, and Fleck’s laboured breathing. There is no slow caressing of Fleck’s body during the violence and neither the visuals nor the audio seems to encourage the viewer to relate to the violence, instead the acoustic space seems designed to disgust us, as Coulthard argues. In these scenes of violence, the promotion of identification through the sensuousness of bodies and melodies described by Kulezic-Wilson is entirely absent; instead, Philips’s film reserves its sensuousness for the process of metamorphosis and not the product. In this way, the film resists triumphalising Fleck’s violence and also resists the kind of empathy and identification with Fleck and Joker that was fostered in the dance scenes.

There is a direct cut from this scene to the dance scene on Step Street, replications of which would become an Internet meme. The beats of Gary Glitter’s “Rock and Roll Part 2” begin as Arthur runs his finger through the blood spattered on his torso.[5] We cut to a shot of the back of Arthur’s head, his hair now dyed green. We follow Arthur from behind as he enters the elevator. The doors open with amplified whooshes and Arthur turns to face the camera. He is now in full clown make up. He slightly sways to the music and cracks a sinister smile. We cut to him dancing on the steps, breathy sounds from his cigarette smoke interspersing with Glitter’s music. Arthur dances with freedom and abandon. His kicks match the pulse of Glitter’s song, the sounds of his steps punctuate the music in time with the beat. Once again, his hips thrust and he curls his arms. It soon becomes apparent that Arthur is also dancing to other music as Gudnadóttir’s score penetrates the soundtrack and drowns out Glitter’s song. Kulezic-Wilson’s ideas of morphing is again relevant here, as the sonic environment transforms from upbeat pop to Gudnadóttir’s score, which in turn transforms our perception of the onscreen dancing. The camera responds to the acoustic shift and Arthur’s legs kick now in slow motion, coinciding with the rhythmic strikes of Gudnadóttir’s mournful music, his jumps and twists all paced in tandem with the sombre strings of the score. Arthur’s dance is interrupted by the interjection of two police officers who appear at the top of the steps. Arthur flees and the two policemen give chase, but he manages to lose them in a crowd of clowns on the subway.

Figures 6 and 7: Fleck in his full Joker costume dancing on the steps. Joker. Warner Bros., 2019.

Arthur continues to dance for the remainder of the film, dividing his dances between private expressive dances that are filled with strange and unsettling bodily contortions and more traditional dance moves in his public expressions of arrogance and swagger. This collision between the dances is seen in his entrance to the Murray Show. In the shadow of the stage curtains Arthur watches as Murray and his guest get ready to introduce him onto the show. Gudnadóttir’s mournful cello music overlays their laughter and discussion of Arthur’s “problems” as Arthur stares at the small television backstage. Murray asks for the clip of Arthur’s stand-up, which he had previously mocked, to be played again. We cut to the stage and see Arthur’s routine being played for the audience. The scene then cuts to behind Arthur, who waits backstage, framed by the stage curtains. He begins to dance to Gudnadóttir’s score in sombre, deliberate slow movements, contorting his body into strange angles. Murray offers a trigger warning to the audience about Arthur’s costume. The intro music for the Murray Show begins and Arthur slithers through the curtains, dancing confidently, to the jazzy music of the show, more reminiscent of Jack Nicholson’s Joker now than any version of Joker presented so far in the film. He is introduced as “Joker”. Here, the dancing immediately precedes the violence and Arthur, now Joker, shoots Murray live on television. He is arrested but the rioters manage to free him and Arthur joins them, venerated by the baying mob. Finding a burned-out ambulance Arthur climbs onto its bonnet. He paints a horrific smile in blood across his face and he outstretches his hands in victory as his adoring fans cheer him on. Gudnadóttir’s score develops into a triumphant anthemic melody with the addition of brass and Joker relishes in his infamy.

Figures 8 and 9: Joker dancing during the riot, performing for his followers. Joker. Warner Bros., 2019.

Conclusion

Paul Booth argues that “[w]e play with the borders and frames of narratives through our own imaginative engagement. As consumers of media, we play with the texts, meanings, and values created by media industries. But playing fandom isn’t just what we do with our everyday media; it’s also what our media do with us” (1). Indeed, some of the criticism of Philips’s film has been that the film was too obviously manipulative of the zeitgeist. Booth’s arguments echo the discussions of film’s haptic and tactile qualities and the film’s framing of Fleck’s dancing encourages empathetic involvement from the viewers. Joker remains a complicated film to submit to, in part because of the culture that grew up around the film online but also its diegetic framing of Arthur’s metamorphosis into the Joker as inevitable or justified. However, while its score, cinematography and acting performances are all compelling, its horrifying violence and the meagre justification provided for it may repel the viewer from its main character and his adoring diegetic fans. And, as of writing, the clear fan adulation for Joker, in all its various Internet forms such as memes, costumed dances and selfies in makeup, has not transcended into emulation of Joker’s violent acts, and instead has been contained to Internet mimicry of his dancing and costuming. There is certainly more to explore here in how the fans reacted to Philips’s film and to its main character, however, it would be beyond the remit of this article.

Kulezic-Wilson argues that “films based on intensified aesthetics synchronize the experience of the spectator with that of the film’s” (Sound Design 96). For Joker, synchronising the experience of the spectator does not necessarily translate to synchronising to the experience of its titular character. While, as I have argued, the intense eroticisation of Arthur’s dancing body and the framing of the music as emanating from his sonic perspective very much attempt to align the viewer’s gaze with Arthur’s vision of himself as newly empowered, the film stops short of aligning our gaze with his acts of violence. While the film’s deliberate attempts to create an empathetic portrayal of Arthur may have justified the costume bans in theatres, for fear that the identification and empathy would foment emulation, it is important to acknowledge that the film’s empathetic moments, its most tactile and haptic moments, are of Arthur dancing, in contrast to its visceral and affective presentation of violence.

Notes

[1] It is well documented in both scholarly and media articles that this toxic fandom had also surfaced in an inverse form to Joker for the all-female Ghostbusters (PaulFeig, 2016), resulting in a surge of negative votes on the YouTube release of the trailer (Sampson; Scott; Hills). These online groups also targeted these films’ female stars. Margot Robbie, who played Harley Quinn in Suicide Squad, received death threats (Rearick) and Leslie Jones, who was one of the female Ghostbusters, had to leave Twitter after a racist and misogynistic campaign was launched against her by fans of Milo Yiannoppolous (“Leslie Jones”).

[2] “Incels” refers to a specific Internet subculture of mostly straight cis-men who claim to be “involuntarily celibate” and blame women for it.

[3] An article by Annabel Driscoll and Mina Husain, two psychiatric ward doctors, provides a deeper analysis of the issues with the depictions of mental health in the film.

[4] Phoenix himself mentions in several interviews that he was specifically trying to emulate the arrogance of some of the dances that he had studied for his role as Joker (“How”).

[5] This was another source of controversy for Philips’s film, as Glitter had previously been convicted of sex offences and sentenced to prison. It was speculated at the time that the cinematic release would not contain Glitter’s music, however this did not come to pass and the song remained in the film.

References

1. Ayer, David, director. Suicide Squad. Warner Brothers, 2016.

2. Bankhurst, Adam. “Joker Costumes Banned From Landmark Theaters’ Screenings.” IGN, 27 Sept. 2019, www.ign.com/articles/2019/09/27/joker-costumes-banned-from-landmark-theaters-screenings.

3. Barker, Jennifer M. The Tactile Eye: Touch and the Cinematic Experience. U of California P, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520943902.

4. Beugnet, Martine, and Laura Mulvey. “Film, Corporeality, Transgressive Cinema: A Feminist Perspective.” Feminisms: Diversity, Difference and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures, edited by Anna Backman Rogers and Laura Mulvey, Amsterdam UP, 2015, pp. 187–202. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048523634-018.

5. Booth, Paul. Playing Fans: Negotiating Fandom and Media in the Digital Age. U of Iowa P, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1353/book38201.

6. Burlingame, Jon. “Composer Gets Into the Head of Joker.” Variety, vol. 346, no. 26, Jan. 2020, p. 21.

7. Burton, Tim, director. Batman. Warner Brothers, 1989.

8. Calvario, Liz. “Leslie Jones Flooded With Racist Tweets After Ghostbusters Release: ‘I’m in a Personal Hell’.” IndieWire, 19 July 2016, www.indiewire.com/2016/07/leslie-jones-leaves-twitter-racist-hateful-ghostbusters-tweets-1201707452.

9. Carroll, Beth. Feeling Film: A Spatial Approach. Springer, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-53936-6.

10. Chavez, William S. and Luke McCracken. “‘He Who Laughs Last!’ Terrorists, Nihilists, and Jokers.” Journal of Religion & Film, vol. 25, no. 1, Article 67, 2021, pp. 1–61. https://doi.org/10.32873/uno.dc.jrf.25.1.003.

11. Child, Ben. “Why DC Fans Should Learn to Love Suicide Squad’s Critics.” The Guardian, 3 Aug. 2016, www.theguardian.com/film/2016/aug/03/suicide-squad-bad-reviews-dc-comic-fans.

12. Collins, Judy. “Send in the Clowns.” Judith, Elektra/Asylum Records, 1975.

13. Coulthard, Lisa. “Acoustic Disgust: Sound, Affect, and Cinematic Violence.” The Palgrave Handbook of Sound Design and Music in Screen Media: Integrated Soundtracks, edited by Liz Greene and Danijela Kulezic-Wilson, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016, pp. 183–93. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51680-0_13.14. Denis, Claire, director. Beau Travail. La Sept-Arte, Pathé Télévision, S. M. Films, 2000.

15. Donnelly, Kevin J. The Spectre of Sound: Music in Film and Television. BFI, 2005. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781838711009.

16. Driscoll, Annabel, and Mina Husain. “Why Joker’s depiction of mental illness is dangerously misinformed.” The Guardian, 21 Oct. 2019, www.theguardian.com/film/2019/oct/21/joker-mental-illness-joaquin-phoenix-dangerous-misinformed.

17. Ehrlich, David. “Joker Review: For Better or Worse, Superhero Movies Will Never Be the Same.” IndieWire, 31 Aug. 2019, www.indiewire.com/2019/08/joker-review-joaquin-phoenix-1202170236.

18. Eisenberg, Eric. “Why Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker Does a Surprising Amount of Dancing.” CINEMABLEND, 16 Sept. 2019, www.cinemablend.com/news/2480315/why-joaquin-phoenixs-joker-does-a-surprising-amount-of-dancing.

19. Elferen, Isabella van. “Haunted by a Melody: Ghosts, Transgression, and Music in Twin Peaks.” Popular Ghosts: The Haunted Spaces of Everyday Culture, edited by Maria del Pilar Blanco and Esther Peeren, Bloomsbury, 2010, pp. 282–95.

20. Feig, Paul, director. Ghostbusters. Sony Pictures, 2016.

21. Gershwin, George, and Ira Gershwin. “Slap That Bass.” Performed by Fred Astaire, Shall We Dance,Brunswick Records, 1937.

22. Glitter, Gary. “Rock and Roll Part 2.” Rock and Roll Part 2, Bell Records, 1972.

23. Godfrey, Alex. “Joker and Chernobyl Composer Hildur Guðnadóttir: ‘I’m Treasure Hunting’.” The Guardian, 13 Dec. 2019, www.theguardian.com/music/2019/dec/13/joker-and-chernobyl-composer-hildur-gunadottir-im-treasure-hunting.

24. Greiving, Tim. “How Hildur Guðnadottir’s Music Helps Shape Arthur Fleck’s Metamorphosis into Joker.” Los Angeles Times, 6 Dec. 2019, www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/movies/story/2019-11-19/hildur-guonadottir-joker-composer.

25. Harris, Hunter. “Warner Bros. Responds to Aurora Theater’s Decision to Not Show Joker.” Vulture, 24 Sept. 2019, https://www.vulture.com/2019/09/aurora-movie-theater-wont-play-joker-warner-bros-responds.html.

26. Hanna, Erin. Only at Comic-Con: Hollywood, Fans, and the Limits of Exclusivity. Rutgers UP, 2019. https://doi.org/10.36019/9780813594743.

27. Hills, Matt. “An Extended Foreword: From Fan Doxa to Toxic Fan Practices?” Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, vol. 15, no. 1, 2018, p. 105–26.

28. Holmer, Anna Rose, director. The Fits. Yes, Ma’am!, 2015.29. Hou, Hsiao-Hsien, director. The Assassin. Central Motion Pictures Corporation, 2015.

30. “How Joaquin Phoenix Perfected His Joker Dance.” Gulfnews.com, 6 Oct. 2019. gulfnews.com/entertainment/hollywood/how-joaquin-phoenix-perfected-his-joker-dance-1.66823128.

31. Johnson, Derek. “Fantagonism, Franchising, and Industry Management of Fan Privilege.” The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom, edited by Melissa A. Click and Suzanne Scott, Routledge, 2018, pp. 85–99. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315637518-47.

32. Kourlas, Gia. “Joker: A Dance Critic Reviews Joaquin Phoenix’s Moves.” The New York Times, 11 Oct. 2019. NYTimes.com, www.nytimes.com/2019/10/11/arts/dance/joaquin-phoenix-dancing-joker.html.

33. Kulezic-Wilson, Danijela. The Musicality of Narrative Film. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137489999.

34. ——. Sound Design Is the New Score: Theory, Aesthetics, and Erotics of the Integrated Soundtrack. Oxford UP, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190855314.001.0001.

35. Lattanzio, Ryan. “Joker First Reactions: Joaquin Phoenix Loses His Shit in a Bold But Incel-Friendly Origin Story.” IndieWire, 31 Aug. 2019, www.indiewire.com/2019/08/joker-reactions-joaquin-phoenix-reviews-1202170199.

36. “Leslie Jones Twitter Row: Breitbart Editor Banned over Abuse.” BBC News, 20 July 2016. bbc.com, www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-36842710.

37. Manalo, Mike. “Inside the Madness of Joker, a Conversation with Todd Phillips and Joaquin Phoenix—The Nerds of Color.” Thenerdsofcolor.org, 16 Sept. 2019, thenerdsofcolor.org/2019/09/16/inside-the-madness-of-joker-a-conversation-with-todd-phillips-and-joaquin-phoenix.

38. Margolin, Josh, and Aaron Katersky. “FBI Will Monitor Violent Online Threads in Light of Joke Premiere.” ABC News, 3 Oct. 2019, abcnews.go.com/US/fbi-monitor-violent-online-threats-light-joker-premiere/story?id=66031356.

39. Marks, Laura U. “Information, Secrets and Enigmas: An Enfolding-Unfolding Aesthetics for Cinema.” Screen, vol. 50, no. 1, Mar. 2009, pp. 86–98. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjn084.

40. McPhate, Christian. “Texas Department of Public Safety Warns of a Potential Mass Shooting During Joker Film Premiere.” Dallas Observer, 27 Sept. 2019, www.dallasobserver.com/arts/texas-department-of-public-safety-find-credible-threat-for-a-potential-shooting-during-joker-premiere-11766959.

41. Nolan, Christopher, director. The Dark Knight Rises. Warner Bros., 2012. https://doi.org/10.5040/9780571343065-div-00000732.

42. Phillips, Todd, director. Joker. Warner Bros., 2019.

43. Rearick, Lauren. “Margot Robbie Received Death Threats After Suicide Squad.” Teen Vogue, 5 Jan. 2018, www.teenvogue.com/story/margot-robbie-death-threats-suicide-squad.

44. Sampson, Mike. “Ghostbusters Remake the Most Disliked Trailer of All Time.” ScreenCrush, 29 Apr. 2016, screencrush.com/ghostbusters-trailer-most-disliked-movie-trailer-in-history.

45. Scott, Suzanne. “Towards a Theory of Producer/Fan Trolling.” Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, vol. 15, no. 1, 2018, p. 143–59.

46. Sinatra, Frank. “That’s Life.” That’s Life, Reprise Records, 1966.

47. Smaczylo, Mike. “Inside Hildur Guðnadóttir’s Haunting Score for Todd Phillips’ Joker.” Muse by Clio, 12 June 2020, musebycl.io/music-film/inside-hildur-gudnadottirs-haunting-score-todd-phillips-joker.

48. Thompson, Anne. “Joaquin Phoenix Talks About Finding His ‘Joker’: Dropping Weight, Facing Fear, and ‘Testing Boundaries.’” IndieWire, 1 Oct. 2019, www.indiewire.com/2019/10/joaquin-phoenix-the-joker-todd-phillips-mirror-1202177432.

49. Wilkinson, Alissa. “Joker Has Toxic Fans. Does That Mean It Shouldn’t Exist?” Vox, 3 Oct. 2019, www.vox.com/culture/2019/10/3/20884104/joker-threats-cancel-phillips-art.

50. Williams, Cameron. “The Rise of Toxic Fandom: Why People Are Ruining the Pop Culture They Love.” Junkee, 13 Oct. 2017, junkee.com/rick-and-morty-toxic-fandom/130622.

51. Williams, Linda. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess.” Film Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 4, 1991, pp. 2–13. https://doi.org/10.2307/1212758.

52. Zacharek, Stephanie. “The Problem With Joker Isn’t Its Brutal Violence. It’s the Muddled Message It Sends About Our Times.” Time, 2 Oct. 2019, time.com/5688305/joker-todd-phillips-review.

Suggested Citation

Shine, Jessica. “‘He Has Music in Him’: Musical Moments, Dance and Corporeality in Joker (2019).” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 27, 2024, pp. 152–168. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.27.14

Jessica Shine is currently a lecturer in the Department of Media Communications at Munster Technological University. She completed a Doctorate on the topic of sound and music in Gus Van Sant's "Death Quartet" in the School of Film, Music and Theatre at University College Cork under the supervision of Professor Christopher Morris and Dr Danijela Kulezic-Wilson. Current research focuses on the use of sound and music in film and television with a particular interest in soundscapes, aesthetics and narrative. Shine has published work on Peaky Blinders, Sons of Anarchy, Crazy Ex Girlfriend, Paranoid Park and Breaking Bad.