Freedom Smothered: Gang Rape as Patriarchal Punishment of Emancipated Women in Yugoslav New Film

Vesi Vuković

[PDF]

Abstract

This article investigates how women and their roles in changing Yugoslav society were represented in Yugoslav New Film (1961-1972). The Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia legalised gender equality in the wake of the Second World War, but the tentacles of patriarchy, which were difficult to eradicate, still lingered from pre-socialist times. In many films from this period there is a recurring pattern of sexual violence towards women. One possible interpretation of depicted sexual violation, for example gang rape in contemporary-themed Yugoslav New Films, is as a patriarchal punishment for the emancipation of women in terms of education, work or their sexuality. In order to examine this, I analyse two case studies, the feature-length fictional films The Return (Povratak, Živojin Pavlović, 1966) and Horoscope (Horoskop, Boro Drašković, 1969), in which the freedom of women’s emancipation was smothered by gang rape. The films are explored via close readings against the backdrop of feminist film theory and the concept of the gaze. Furthermore, I scrutinise whether these representations of rape and their aftermaths condone or condemn brutality toward female characters or if they have a rather ambivalent stance toward it.

Article

The feature-length fictional films The Return (Povratak, Živojin Pavlović, 1966) and Horoscope (Horoskop, Boro Drašković, 1969) highlight how the freedom of female emancipation is smothered by gang rape. In these examples of Yugoslav New Film (novi film), progressive, emancipated in terms of work, or sexually-free female characters are suppressed in the narrative. Sexual violence, in these films, comes as a punishment to liberated women for challenging the patriarchy. Represented rape is a means to confront the threat of active female sexuality or power with the phallus as a weapon to subjugate sensual or independent women.

The Yugoslav New Film (1961-1972) occurred as a part of worldwide New Wave movements, such as the French nouvelle vague, the Brazilian cinema novo, the Japanese nūberu bāgu and the Czechoslovak nová vlna. Notable YugoslavNew Filmdirectors were, for example, Dušan Makavejev, Aleksandar “Saša” Petrović, Želimir Žilnik, Boštjan Hladnik, Matjaž Klopčić, Vatroslav Mimica, Ante Babaja, Bahrudin “Bato” Čengić and my two case study directors Drašković and Pavlović. To Drašković, Yugoslav New Film is a rediscovery of the medium that includes a new sensibility, new freedom, new reality and new sensory, ideological and moral clarity (Petrović 330). Since Yugoslav New Film directors are auteurs, with their own film language and aesthetics, there is a corresponding conceptual, thematic and stylistic variety in Yugoslav New Film (Petrović 330). In Pavlović’s view, the Yugoslav New Film does not seek to please, but to torment, by putting pressure on the viewers’ ethical, political and societal conformism (Novaković and Tirnanić 5). Yugoslav New Film directors want to show “subjective truths, subjective perceptions of life, of people, of their position in a society, and not just in our [Yugoslav] society, but in societies in general” (Pavlović 231; my trans.). In fact, Pavlović finds that his films, and films of other Yugoslav New Film auteurs, would not be what they are if they were addressing only Yugoslav problems, instead of problems that are universal and imposed to people regardless of where they live (Pavlović 236). In Yugoslav New Cinema, “heroes are the defeated, the bewildered, and the unsatisfied savage young” (MoMA 1). Indeed, in the films discussed in this article, the heroes are such young men. But what about the heroines of those films?Yugoslav New Film often “flaunted the drastic images of femininity, either positing the women as embodiment of the social sins, or as subjected to extreme physical and sexual violence and sometimes as both” (Jovanović, “Gender” 29). One possible reading of depicted sexual violence, more specifically of represented gang rape in contemporary-themed Yugoslav New Films, is as a patriarchal punishment for the liberation of heroines in terms of work, their active sexuality, education or their right to choose and refuse men freely.[1] It is important to bear in mind that Yugoslavia was a socialist society, which ratified gender equality by law in the wake of the Second World War, so the roles of women in society were changing, to the dismay of the remnants of patriarchy that still lingered from pre-socialist times. A close analysis will examine the two selected films through the lens of feminist film theory and the concept of the gaze. Moreover, I will investigate whether these representations of rape and their aftermaths condone or condemn violence toward women, or rather take an ambiguous stance.

Rape in Cinema and Emancipation of Women in Real Life

In the United States, culminating in the early 1970s, there was an unheard-of number of films featuring female rape (Kaplan 7). The emancipation of women and their growing power in real life, influenced by the feminist liberation movement, caused what can be described as a counterattack in cinema (Haskell 323). One of the cinematic mechanisms for subjugating women and obscuring patriarchal fears is rape; according to E. Ann Kaplan, the threat of increasingly free female sexuality had to be confronted with the phallus as the main weapon for controlling women (7). Historically, films that included rape scenes frequently associated sexual assault to a woman’s independence, by following one of two patterns: either a woman was dependent and, thus, vulnerable to rape due to her fragility or she was independent (sexually or otherwise) and, consequently, had to be disciplined into submissiveness by sexual violence (Projansky 97).

In a similar vein, in regard to Yugoslav New Film, Greg De Cuir posits that beating, heinous killing, and rape as an indicator of the repression of women’s sexuality, are recurring forms of assault, occasionally all appearing in one film (109). The motive for frequent brutality aimed at women in Yugoslav New Film is for De Cuir the fear of their strength and determination, the traits utilised in the revolutionary struggle during the Second World War, where women fought shoulder to shoulder with men against the Germans and their allies (109). Nevertheless, when peace came, women ceased to be indispensable for the role of Partisan soldiers, but, as society prospered, they also no longer fit into the role of a housewife (De Cuir 109). They became emancipated by finding employment, which secured them financial independence, and by becoming sexually free and dating men, without necessarily entering the institution of marriage as before (De Cuir 109).

Socialist Yugoslavia ratified and advocated gender equality (as a reward for women’s indispensable participation in the Second World War), starting with its first postwar constitution of 1946, which legally equalised women with men, thus guaranteeing significant improvements, such as women’s rights to vote, to equal salary and to paid maternity leave (Ramet 94-5). Socialism empowered women with unprecedented political, social, economic and reproductive rights (Kralj and Rener 42). However, the contradictions of Yugoslav socialism were such that, despite the enormous progress made by women in the production and public spheres, in the domain of interpersonal relations between women and men, deeply rooted, old, conservative values lingered from pre-socialist times, especially in less-developed and rural parts (Morokvašić 135). An influx of population from villages to cities had a consequence that patriarchal, traditional ways of thinking, typical for agrarian environments, were retained in cities as well to some extent (Gudac-Dodić 91). Nonetheless, when compared to Western countries, the position of women in Yugoslavia was better in relation to more favourable policies regulating social and legal equality (Kralj and Rener 43). Moreover, the prevalent opinion among scholars is that Yugoslav women had more rights before the wars of secession than they do today in the former Yugoslav republics (Hofman 193). Keeping in mind the emancipatory rights women gained in Yugoslavia (including marriage, divorce, inheritance, education, employment, reproduction and political rights), I investigate the potential link of those gains to the prevalence of the rape motif in Yugoslav cinema. I read the gang rape of passionate, independent and progressive female characters-specifically in Yugoslav New Films set in their contemporary times-as cinematic patriarchal punishment, caused by the accumulated anxiety and threat that women, due to their real-life emancipation, posed to the remnants of the patriarchy.

Modernity vs. Tradition

In Pavlović’s film The Return a waitress, after rejecting a pushy customer, is implicitly gang-raped by him and his friends on her way home after the end of her shift. She is a supporting character, who develops platonic feelings for the main character nicknamed Al Capone (Velimir “Bata” Živojinović), a reformed criminal. He is trying to lead an honest life after getting out of jail and to reintegrate into society. However, it is all in vain, since he is mistakenly killed by police for a crime he did not commit, just as Vidak (Dragan Nikolić), the main character of Horoscope, as they were both attempting to board on a moving train in order to escape the police. Another common denominator between the films is black and white photography. Also, in both films, female protagonists are initially empowered by employment, but after rejecting pushy men that they meet for the first time at their workplace, they are consequently gang raped. In The Return sexual violence is implied, while in Horoscope it is explicitly shown.

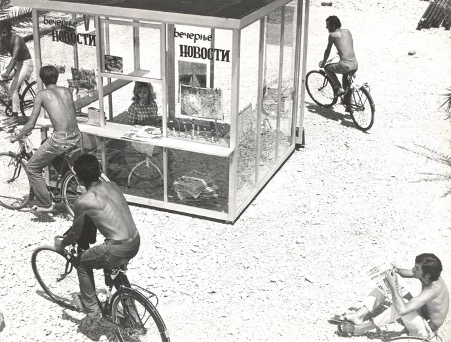

In the latter film, directed by Drašković, Milka (Milena Dravić), a beautiful, young blond woman, is gang-raped by a group of indolent men after she declines the advances of one of them, the previously mentioned Vidak, and instead chooses a man from outside of their clique. These five lethargic, unemployed, aimless young men spend their hot summer days hanging around at a beer garden (be it open or closed) of a new, unfinished but functional train station in a Yugoslav provincial town in a region called Herzegovina. The tedium of their lives is underlined with the fact they can tell time according to the arrival of trains that briefly stop on the way to the sea, and whose timetable they know by heart. The film stresses some societal issues, such as youth unemployment, reflected in male characters’ lack of motivation and destructive channelling of energy. The monotony of the environment is broken with the arrival of Milka, a supporting character, who starts working at a kiosk. She sells newspapers with news from the outside world and, as an urban, modern girl, presents a novelty for the aimless young men from the small-town. Soon, Milka becomes the object of their gazes and of their desire. In general, she is constantly pursued by men she does not want, but who do not take no for an answer. The reason why, in the first place, Milka moves from an urban environment to such a remote, provincial small town is to escape from her former partner, who tracks her there. It is implied that she suffers physical or sexual violence from him during their meeting. However, since he leaves for good, it becomes obvious that she has courageously refused to go back to him, no matter the cost. Another person who tries to coerce Milka into being with him is an elderly, overweight stationmaster, who takes her to a secluded place after a dance, under the pretext that he will give her a ride back home. Although he chases her on his motorcycle (Fig. 1), she eventually manages to escape by running away.

Figure 1: Still from Horoscope (Boro Drašković, Bosna Film, 1969).

Courtesy of the Archive of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Even what appears to be an innocent game of the aimless youth gang foreshadows their sexual violence towards Milka. Four of them start riding bicycles around Milka’s kiosk, which is completely made of glass and see-through, thus resembling a fish tank or a glass cage, around which predators are circling (Fig. 2).[2] Simultaneously, the threatening howling of a dog is heard a few times. However, there is no such animal to be seen in the whole film, nor does it appear that the young men, who are laughing, are producing the sound in question. I contend that the extra-diegetic howling is the director’s deliberate hint that this clique of young men can quickly transform into a pack, prefiguring their behaviour of sexual predators towards Milka, their prey. The only one who does not participate in the cycling game is Vidak, who remains seated on the ground, leafs through the newspaper and observes them, which also foretells to some extent his behaviour during the gang rape. The rest of the clique barge into Milka’s glass cage and playfully cover her with newspaper. The unsuspecting Milka, who has just recently met them, finds it amusing, but her amiability towards the young men will eventually cease. Vidak has made a bet with Kanješ (Miloš Kandić) that he will have sex with Milka within seven days or lose his rowboat. In order to beat his rival, Kanješ reveals this to Milka, who for a short while even seemed interested in Vidak, so he loses any prospects of winning the bet as Milka rejects him. However, she is more than a wager for Vidak. Simultaneously, Milka is an object of his desire and the aim of his twisted, unrequited feelings. It becomes clear that she has stopped finding their pranks benign when one of them, Alija (Dragan Zarić), steals her dress from the clothesline and cross-dresses to tease her, but she only ignores him.

Figure 2: Horoscope. Courtesy of the Archive of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The sexist way of thinking of the small town, that sees a woman as a source of all problems, is exemplified by a chauvinistic statement about Milka by the stationmaster, whom she rejected earlier: “Where there is a woman, there is trouble.” In addition, later in the film, Kanješ, one of the clique members, slanders Milka that she “wants to do it with everybody”. Although this account is not true, it is telling of the patriarchal ideology of young indolent men, who find themselves entitled to a woman’s body, regardless of how she feels about it. A grand misogynist fantasy is about the tempting, libidinous and sex-driven woman who fantasises about being raped (Haskell 363). If the clique establishes that Milka wants to do it with everybody, then she must want to do it with them as well, even by force. They put the blame on the woman, as if it is her fault that she will later be gang-raped by them, which, as Sarah Projansky contends, confirms “links between rape and men’s control over language and the gaze” (122).

In The Return, Bigi (Nikola Čobanović), a pushy, crude customer, initiates the verbal and physical sexual harassment of Gordana (Snežana Lukić) in the bar where she is employed. Whenever she passes by his table, carrying a tray on the way to serve other customers with drinks, he tries to block Gordana’s path with his arm, or to grab her by her arm. Also, he catcalls her “dupence”, meaning “little butt”, as well as “ajkulice” (“little shark”), because “Ajkula” is the nickname of her brother, who is the leader of a criminal group that has been feuding with Bigi’s criminal group over power. Gordana herself is not involved in criminal activities but earns her living decently. To Bigi’s sexist advances, Gordana responds by calling him a swine and hitting him on the head with a kitchen towel, which is more a symbolical act than one intended to physically hurt him, to which Bigi threatens her and tactically retreats. The Return underscores the contrast between Bigi’s backwards mentality and female emancipation, tradition and modernity, the outskirts and the capital Belgrade, the margin and the centre.Similar to the clash between rural and urban in The Return, in Horoscope a small remote town is undergoing modernisation. While the young gang seem to be open towards progressive Western influences, such as rock music and jeans, their deeply rooted sexism culminates in the explicitly shown gang rape of Milka. She is a supporting character, whose function is to contribute towards the creation of the overall impression of a clash between urban progress, for which she stands, and the rural traditionality of a small town, that nominally embraces modernity while clinging onto its patriarchal attitudes, especially towards emancipation of women. Because in the mass media, which generally hindered gender equity by transmitting its values, woman is represented as rather vulgarly sexually objectified, “in the eyes of the village people, the emancipation or liberation of women often means becoming ‘easy women’, who adopt the loose morals of the towns” (Morokvašić 135). Yugoslav film critic Bogdan Tirnanić recalls a real-life gang rape that a group of male perpetrators committed in Ivangrad, a Yugoslav small town. He draws a parallel between the film Horoscope and real life, with a difference that in the film the female newspaper seller is raped, while in the real life one of the Ivangrad rapists was a male newspaper seller (Tirnanić, “Kamerom”; my trans.). Together with his friends, the male newspaper seller sexually violated an American girl, whose “transgressions” included walking in a miniskirt in Ivangrad (Tirnanić, “S”; my trans.). Tirnanić highlights victim-blaming excerpts from a court stenographer’s transcript during the closing remarks of the trial to the Ivangrad rapists: “Such free behaviour [...] is unusual in our environment. There was a clash between, so to speak, two worlds, two environments, two perspectives. Her behaviour was understood by young men as a challenge” (qtd. in Tirnanić, “S”; my trans.). Tirnanić finds that, since in small towns individuality and privacy are considered as transgressive and as a challenge to such close-minded environments, the guilt of the heroine of Horoscope is

in her wish “to keep her human content from mixing with the content of the small town” (Tirnanić, “S”; my trans.). In Tirnanić’s view, the cruel scene of gang rape in Horoscope is not so much the result of sexual lust of provincial studs, but rather a demonstration of provincial anger over things that escape control, over things that want to stay outside of the [provincial] mechanism and which do not obey, over things that are special. Something like that is a powerful challenge and brutality will be used by any means necessary for the purpose of punishing such temerity, such heresy called individuality. For the [anti]heroes of Horoscope the rape of the newspaper seller is a matter of provincial honour, of a worthy answer to the challenge. (Tirnanić, “S”; my trans.)

Bearing this in mind, I pose the question of whether and to what extent directors, by simultaneously contesting and condoning sexual violence, in prevalent representations of female rapes and gang rapes in Yugoslav cinema, inadvertently contributed towards fostering and normalising patriarchal practices.

Gang Rape

Michelle Moore draws a parallel between a film director and a voyeuristic, sexually exploitative male character, who is a source of the brutality towards represented women (137). Over the course of around fifty years, Yugoslav films have almost always been directed by men, who frequently stereotyped young female characters as cruelly sexually violated, maltreated or viciously beaten, and often of low morals (Ugrešić). According to Svetlana Slapšak, American screenwriter Andy Horton, who viewed a considerable number of Yugoslav films, observed that love scenes were seldom shown, while rape scenes were prevalent (“Representations” 37). In fact, from the second half of the 1960s, rape is one of the most frequent motifs in both Yugoslav New Film and its contemporary mainstream cinema (Slapšak, “Žensko Telo” 134-35). In Yugoslav cinema, rape-frequently as a means to discipline a female character’s active sexuality-is fetishised, often via the subjectivity of a male character (Jelača 326). In such Yugoslav films that feature sexual violence, recurring shots depict the savagely ripping of female clothing, and a female naked breast groped by a male hand (Ugrešić), accompanied by the wailing and screaming of a raped woman (Slapšak, “Žensko Telo” 134). As seen from that perspective, Yugoslav cinema presents a devastating representation of the image that a Yugoslav man has about a woman (Ugrešić). Besides the stereotype of the raped girl, other basic types of women in Yugoslav cinema are the prostitute (or its variation, the singer) and the mother in black, permeating both war-themed films set in the past and contemporary-themed Yugoslav films (Slapšak, “Žensko Telo” 135). Such a typology is visible, for instance, in the films of Pavlović (135). Historically, film has been a male-dominated art form, and Yugoslav feature-length fiction film is no exception as there are very few female directors (only Soja Jovanović during the period in question); consequently, “the approach to a female character is almost always burdened with male complexes and male prejudices” (Boglić 122; my trans.). Haskell notes that some American auteur filmmakers imbued their sexual frustrations into the treatment of female characters in their films (326). Furthermore, in certain Hollywood films, cinematic sexual assaults allow, to a significant extent, the viewer’s identification with the perpetrator (Clover 152). A female character not only “embodies the violent fantasies of two men”, a director and a writer, but also of a culture they belong to in general (Vincendeau).

It must be considered whether directors Drašković and Pavlović exploit the representation of the female body during the sexual assault sequences. In both The Return and Horoscope, the right of a heroine to reject harassing men is taken away from them by gang rape, which comes as both a punishment and as the revenge of rejected patriarchal men. Projansky points out that film “rape narratives historically often linked rape to women’s independence” (97). In contrast to Yugoslav real-life emancipation by labour that was beneficial for women, in these films female employment is represented as perilous, because the heroines initially encounter their rapists at their workplace. Namely, as we saw, in The Return, Gordana turns down the offensive sexual advances of the customer Bigi in a bar where she works as a waitress. Emancipation brings an awareness that every woman should be entitled to choose and to refuse her partners freely. The rejected Bigi prophetically threatens Gordana that she will pay on the football pitch. Nevertheless, he ostensibly leaves her alone because she is protected by another customer and goes away. When the bar scene ends, suddenly there is an ellipsis and Gordana is shown running desperately outdoors. It can be deduced that the director, in order to condense time and to shock the viewers, deliberately omitted depictions of what Gordana did at work until she finished her shift, as well as of how the antagonist plotted with his gang members to attack Gordana on her way back home after work. So, unexpectedly, there is a pack of seven men pursuing Gordana, until they encircle her on an isolated outdoor football pitch covered with snow and corner her in the goal net. During the chase, it becomes noticeable that Bigi limps as he runs, which is the rather stereotypical choice of director Pavlović to attribute a physical disability to the character in order to villainise him. However, Pavlović, in sync with his director of photography Aleksandar Petković, creatively employs tones of black and white cinematography, enhanced by preselection of costumes in certain shades; for example, due to wearing a light-toned coat, Gorana stands out from her attackers, who are clad in dark clothing. This contrast possibly evokes the conflict of good and evil, in which she, the white figure, resists futilely, and is bound to lose. As Projansky would have it, female characters “may act independently, moving about alone in public space, working for a wage, or defending themselves, but still face sexual violence” (35).

The antagonist pushes Gordana into the net. There is a long shot of one of the pursuers, who intentionally lies down on his stomach in the snow, somewhat further from the goal, but it is unclear what he is doing while crouched, whether he is masturbating, mirroring Gordana, or something else. Perhaps this is in line with what Ann Cahill described as a situation in a film in which “the rapist requires another man to view and validate his status as a rapist” (118). The next shot features multiple planes, the antagonist Bigi in a close-up in the middle ground of the complex composition, filmed through the net in the foreground, while there is another perpetrator visible in the blurry, out-of-focus background on the right. It is underscored by a disturbing off-screen female scream. The antagonist grabs the net and moves downward, out of frame, in the direction of the invisible Gordana, who is most probably on the ground, pinned down inside the net. The shot finishes with a second disconcerting off-screen scream, clearly suggesting the sexual abuse. The woman is eradicated from the frame, just like her integrity as a human being is obliterated with the act of sexual violation. The next shot is a detail of a phallic machine used for welding, throwing sparks around. Even though it belongs to a new scene, juxtaposed to the previous one, it enhances the upsetting, visceral impression of the gang rape.

In contrast to The Return, in which the act of rape itself is not shown, but implied, in Horoscope there is graphic portrayal of rape. While explicit depictions of rape fetishise it, in implicit scenes sexual violence remains unrepresented and, thus, not fetishised (Jelača 326). Nevertheless, what is not seen, and is imagined instead, is possibly equally as gruesome. However, explicit depictions of sexual violence “can be understood to express hatred for and violence against women and thus can potentially increase anxiety and discomfort for many spectators” (Projansky 95).

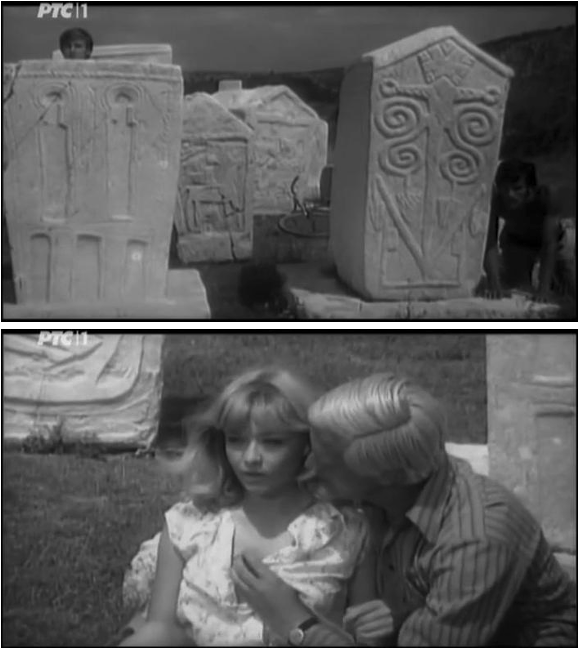

In Horoscope, explicit sexual assault begins on the occasion when Milka willingly goes to meet a man she likes at the archaeological site where his work is based, amongst picturesque ancient tombstones called stećci. Their sexual foreplay is observed and halted by the clique of four rejected indolent young men (Fig. 3), who have followed Milka. After the man uncovers Milka’s nude breast (Fig. 4), the voyeuristic gang makes its presence known by throwing pebbles next to the passionate couple. According to Laura Mulvey, voyeurism is closely linked to sadism where pleasure lies in, for instance, the punishment of a woman (Visual and Other Pleasures 21-22). Therefore, it is not surprising that the men’s voyeurism quickly alters into sadism. In the male-dominated milieu, the impending degradation of the heroine’s sexuality by rape implies degradation of her personhood (Ranković 259). It is not enough for the young men to watch, they want to punish Milka for wanting to have sex with another man instead of with them, which will eventually spiral into gang rape by them. This illustrates misogynist rationale, as Hannah Hamad would put it, which assumes that free female sexuality bears culpability for male sexual attack (248).

Figures 3 and 4: Horoscope. Screenshots.

The four men from the group start chasing Milka. She climbs on her bicycle in an attempt to escape, but the pursuers, unlike the man Milka was with, also have bicycles. They catch up with her, and eventually push her and her bicycle off the main road into the river. She manages to get out of the river, but they encircle her on the shore. To borrow Cahill’s phrase, “[t]heir masculinity [...] must be established sexually for and in front of each other in order to be sufficiently grounded” (118). This observation is applicable to Horoscope because the gang rape, undertaken by the members of the male pack, must be witnessed by each other. Kanješ rips off Milka’s dress in the breast area, which is, as previously mentioned, a recurring stereotypical shot in Yugoslav films that feature female rape. The breasts are visible only for a brief instant, as a flash, because Milka pulls the ripped material to cover her nudity. Once more, Kanješ rips her dress, though on the back this time. She tries to escape, but he catches her, lifts her up and brings her to Vidak. The four assaulters push Milka to each other as if she were an object or a commodity. It is a hot summer day, and the assaulters are naked to the waist. This is indicative of Drašković’s fascination with young male bodies, as well as of the echo of homoeroticism in the gang rape sequence (Radić 105). Milka tries to fight the attackers off with all her strength yet is dragged to the ground. Since she is wearing a dress, during the struggle her bare legs are exposed to the thigh, although not in detail. Her body is sexualised and objectified, but not fetishised at this point. Still, it evokes a question posed by Tanya Horeck: “Are we bearing witness to a terrible crime or are we participating in a shameful voyeuristic activity?” (vi). After Milka is overpowered, she eventually becomes numb, helpless, and with an empty gaze signifying her powerlessness. To borrow Victoria Anderson’s observation, “rape as an expression of power pivots on the consumption of the victim’s will-a process by which the perpetrator is empowered by the introjection of another’s agency” (80). During the gang rape penetration, while each rapist takes his turn and others restrain Milka’s hands, the director refrains from showing her nudity. Instead, the focus is on her terrified face, with an expression as if she is gasping for air, burdened by the weight of three consecutive, violating, unwanted male bodies. Under them, she sometimes completely disappears, disintegrated below the naked male shoulders.

However, when Vidak’s turn comes, the nudity of Milka’s breasts is fetishistically shown, at first for a brief instant before he slowly kisses her on the lips, as they are both shot laterally in the profile. For him she is fetishised, therefore revered and, in a twisted way, loved. Milka is unresponsive and catatonic. Kanješ, one of the rapists, says, “Be brave, young man, this is your last chance to win the bet.” Vidak, shown frontally in a two-shot on top of Milka, who is underneath him, restrains himself. Either he realises that he has hurt himself by punishing the object of his unrequited desire via proxies, or his conscience awakens due to his complicity with the multiple rapes Milka endured. As he stands up to join his three rapist friends, who are already leaving, Milka remains alone in the shot, laying on her back, while the shape of her naked breasts is deliberately highlighted by director Drašković, and his director of photography, Ognjen Milićević, via camera framing and lighting. To borrow from Mulvey, “[t]he power to subject another person to the will sadistically or to the gaze voyeuristically is turned onto the woman as the object of both” (Visual and Other Pleasures 23).

Sound of Rape

Contrary to Drašković’s visual aestheticization of the gang rape scene, that diminishes the gravity of the brutal act, his soundscape of the scene augments it. Linda Williams notices that Hollywood sound cinema often softens the rawness of “penetrative blows” by underscoring them with music, as if the representations of sexual violence and sex in general are bracketed off from the rest of the film in another space and time (84). In contrast, in examples from European cinema, such as The Virgin Spring (Jungfrukällan, Ingmar Bergman, 1960) and Two Women (La Ciociara, Vittorio De Sica, 1960), the raw aural component of sexual brutality towards women enhances its impact during screening (84). Contrary to the underscoring of sexual violence scenes with music which distances the rape, making the sounds of sexual violence audible renders it “more proximate to the viewer-listener” (83). Hence, director Drašković’s usage of the ambience sounds that are audible in Horoscope during sexual assault, as the tearing of the dress, grinding of struggling bodies on the pebbles, Milka’s helpless moans and a scream, make the sexual abuse more viscerally experienced by approximating it aurally to the viewer. However, during the rape penetration in particular, such sounds are silenced.

When the first rapist, Kanješ, climbs on top of Milka, just before the forced sexual intercourse begins, there is a brief, uncanny exchange of looks between her and Vidak in close-ups, and then she screams. The scream is soon followed with an amplified, repetitive sound of the metal train wheels in motion on tracks that outvoices all other sounds, imposes its dominance over all of them, and corresponds to the bodily motion of the rapist as he rapes Milka. The director intentionally uses the train sound, possibly to dramatically accentuate the gang rape, but also to express the helplessness and hopelessness of Milka’s situation, for whom there is no escape. No one is there to hear her since she is silenced by the sound of train. There is one-time synchronicity, when the locomotive whistle is juxtaposed to Milka’s face, frozen in a silent scream, with the mouth wide open, but mute. Such combination of sound and image editing resembles Alfred Hitchcock’s method in, for example, The 39 Steps (1935), where, according to Thomas Leitch, an old woman turns “toward the camera to scream, only to have the sound of the scream covered by the sound of a train whistle” (20). When the other two rapists climb on top of Milka, the rapes are also underscored with the train sounds. Nevertheless, it could be debated whether the sound of the train softens the impact of the rape for viewers or otherwise. When Vidak, the fourth and last of the group, has his turn to rape Milka, the sound of the train stops, as if the train passed. With this sound intervention, the director wants to morally differentiate Vidak and his actions from the perpetrators of the three preceding rapes.

In contrast to Drašković’s decision not to use music in the gang rape sequence in Horoscope, in The Return Pavlović underscores dramatic, instrumental, extra-diegetic music, in order to deepen the tension of Gordana’s chase by a pack of men and the bleakness and desperation of her position. The music is heard while Gordana is pursued in the streets, and shortly after she is hounded into the football pitch, where the music ultimately stops. On the one hand, Pavlović’s decision to use instrumental music only up until this point, halfway through the sequence of sexual assault, intensifies the drama of the hunt as long as there is a hope that Gordana might manage to flee from the pack of men who want to rape her. On the other hand, Pavlović’s choice to stop the music here signals the impossibility of Gordana’s escape from the rapists. From this point on, only diegetic sounds are audible, as Gordana’s cries for help and screams, amplifying the terror of sexual violence. This is in line with Williams’ theory that if the music is deliberately omitted, and instead the raw aural component of a sexual assault is rendered audible, the sexual violence is brought closer to a viewer/listener. When the instrumental music stops, Gordana breaks the silence by screaming for police and people’s help, but no one comes to her rescue. She cries “police” once more, again in vain. Then, her next scream for help is directed at people in general, for someone, anyone, to save her, but no one is there to hear her. This could be interpreted as a critique of the society and police in the sense that they are not to be found when needed. After Gordana is cornered inside the football net, a close-up shot of the main culprit, Bigi, is shown, as he descends threateningly towards where she appears to be off-screen on the ground, while another rapist is also approaching her. Over that shot, her two chilling, off-screen screams are heard, suggesting the implicit sexual assault of Gordana in the football net. That is when the gang rape sequence abruptly ends.

Mulvey Revisited and Revised: Female Gaze and Trauma, Male Gaze and Voyeurism

Later in The Return, having been sent there as a messenger on behalf of her criminal brother Ajkula, Gordana is in the grandstand overlooking the football pitch where she was gang-raped; a familiar melody becomes audible, namely, a variation on the theme of the instrumental music that was heard during the sexual assault sequence. The music is linked to Gordana’s subjective point-of-view shots of the players on the football pitch during a game. Thus, Gordana’s trauma is underlined by these point-of-view shots, in which the framing of the players on the pitch recalls the framing of the sexual assaulters in pursuit of Gordana, in the gang rape sequence earlier in the film, shown from an objective, omniscient, third-person perspective. Moreover, the camera position from which the football players are filmed in the long shot, their trajectory and their directionality, from left to right, are the same as of the rapists’ during the hounding of Gordana on the football pitch. There is another point-of-view shot of the players, this time captured through the goal net in the foreground (Fig. 6.1). This evokes the camera placement during the sexual assault, that encompasses the villains and Gordana, filmed through the net (Fig. 5), as they corner her inside the football goal, as seen from an objective, third-person perspective. Gordana’s aforementioned, subjective point-of-view shots of the football game (Fig. 6.1) that recall the sexual violence sequence are edited with the matching shots of her face in close-ups (Fig. 6.2), in which she recoils at the sight of the place where she was attacked. This suggests the consequences of the gang rape on Gordana’s psyche as an unhealed traumatic experience. To borrow Anneke Smelik’s observation on director Marion Hänsel’s rape-themed films, “[s]exual violence is represented as a traumatic experience that haunts women for the rest of their lives” (80). Therefore, Gordana’s inner state of mind is made known to the viewers, by both visual and aural means. It was not very common in Yugoslav New Film for a director to show a female perspective on the post-rape feelings of a heroine, especially through a woman’s point-of-view shots, like Pavlović did.

Figure 5: Gang Rape of Gordana. The Return (Živojin Pavlović, Avala Film, 1966). Screenshot.

Figures 6.1 and 6.2: The Return. Screenshots.

Gordana’s point-of-view shots are an infrequent example of the female gaze in Yugoslav New Film. When Mulvey introduced the concept of the male gaze, initially she omitted the female gaze, and implied its impossibility by putting forth that women are depicted as passive objects to be looked at, not intended to actively look themselves, while a man is an active bearer of the gaze. For Mulvey, the male unconscious fears that women were possibly castrated because they lack a penis, and, therefore, the same could happen to men (Visual and Other Pleasures 21). The castration anxiety a woman provokes is subconsciously sublimated by male psyche with fetishistic scopophilia and sadistic voyeurism. The first remedy-fetishistic scopophilia-fetishises the woman by fragmenting her body in close-ups, or by completely transforming a represented whole female figure in a fetish (21). The second remedy-the pleasure of sadistic voyeurism-scrutinises the woman and investigates her guilt, since, if she was castrated, she presumably had to be guilty of something. Consequently, the culpable woman is either punished or pardoned, but the latter is only if she is reformed by being brought back on the right path. Punishment with sexual violence “symbolically points to woman’s castration in its extreme: the lack of phallus highlighted forcefully through the act of being overpowered by the phallus of the other” (MacDonald 66).

Mulvey has been criticised by film feminists for initially not addressing the female gaze or female spectator, as well as queer spectator and varieties of spectators of colour, age or class (Bergstrom and Doane 9-10). For instance, Mulvey did not originally specify what happens in those examples where women do look and their perspective is shown, as is the case of Gordana. Film feminist scholars as Smelik observe that the creation of a female gaze-when a heroine is granted point-of-view and the camera look is associated with her eyes-is subversive because it “exposes and criticises male violence, divorcing it radically from erotic pleasure” (84). The female gaze is rather not voyeuristic and impedes the male gaze by underscoring a woman’s experience (84).

While in The Return Pavlović briefly uses the female gaze to visually and aurally convey Gordana’s rape trauma, Drašković does not feature corresponding shots in Horoscope. Despite the fact that Milka is occasionally in possession of a gaze, her point-of-view shots inform about her new environment and the indolent young men she meets, rather than about herself. They are an example of what Mulvey dubs in her later work “the female gaze of curiosity and investigation” (Fetishism 62). However, she is gradually deprived of such intermittent point-of-view shots, which signals her progressive disempowerment at the hands of men. In contrast to constructing Milka’s female gaze as less significant, and towards the end of the film as usually absent, director Drašković constructs the male gaze as memorable and voyeuristic, as demonstrated on several occasions throughout the film when the indolent youth clique members stare at Milka and other women.

The combination of both fetishistic scopophilia and sadistic voyeurism is present in a scene taking place before the gang rape where Vidak sneaks into Milka’s room. After already being rejected by her, he resorts to invading her privacy and observing her without her knowledge. When Milka enters her room, she takes off her shirt in medium shot (Fig. 7.1), remaining in lingerie, as seen subjectively by Vidak who peeps from underneath the bed. The camera is positioned at low angle and the framing is suggestive of an intruder’s point-of-view, especially because there is a visual obstacle in the upper right corner of the frame created by a bed sheet. In the next shot, Vidak is revealed as the one who spies on Milka while she undresses. Framed in medium shot, lying laterally, he lurks from his hiding place (Fig. 7.2). Again, Vidak’s subjective point-of-view shot follows, this time fetishistically singling out a detail of Milka’s legs as she takes off her skirt, lingerie and pantyhose (Fig. 7.3). In Mulvey’s opinion the shattering of the unity of female body by singling out a detail, such as of a face or legs, imbues eroticism into film narrative by turning a woman into icon, which removes the impression of realism because the depth of field is significantly reduced, and instead introduces fetishism into representation (Visual and Other Pleasures 20). Hence, director Drašković objectifies and fetishises Milka via the proxy of the character of Vidak.

Figures 7.1, 7.2 and 7.3: Horoscope. Screenshots.

Milka enters the bed in a long shot that encompasses both of them, her on the bed and Vidak below. She turns on the radio and falls asleep. “Peeping Tom” Vidak emerges from his hiding place, watches her as she sleeps and turns off the radio before he exits the room, a gesture that discloses a caring sentiment. With this scene director Drašković reveals something about Vidak but doesn’t divulge anything about Milka. Milka’s perspective, as seen in her point-of-view shots, is lacking here, as well as, for instance, in the gang rape sequence, in the post-rape scene and in the scene of her departure from the small town. So, her subjective take on those detrimental and upsetting events is omitted.In contrast, it is surprising that director Pavlović, who made some rather sexists remarks about women in his books and interviews (Jovanović, “Zazor” 210; Pavlović 210), actually gives his heroine Gordana a female gaze in order to convey her rape trauma in The Return. Nevertheless, even on the exceptional occasion of female gaze in the scene described above of Gordana’s point-of-view shots of the players on the football field, she is simultaneously observed by Al Capone (who sees her for the first time after six years served in jail). Namely, a close-up shot of him in profile, as he looks in her direction, is embedded within Gordana’s aforementioned, short rape trauma sequence. Therefore, even in the infrequent case when Gordana does possess female gaze, it is fleeting and controlled by the male gaze. In general, a female character in Yugoslav New Film has the power of female gaze only rarely, only briefly or only while she is observed by a man.

Post-Rape Perspective

As previously mentioned, Milka’s rape trauma in Horoscope is not depicted via her point-of-view shots. Immediately after the gang rape, a distraught Milka is shown in the foreground of a close-up shot, in which her face is obscured by her messy hair, while the rapists are visible in the distant background as they leave on their bicycles. Then, she submerges herself in the river. Possibly the most frequent manner of depicting a woman’s post-rape perspective in a film is in a scene where she cleanses herself by bathing or showering, which is consistent with the feminist argument that women who were sexually violated feel dirty after the rape (Projansky 108). Milka’s post-rape scene of cleansing includes an extreme long shot from high angle, suggesting her utmost desolation. Director Drašković, therefore, gives a female perspective by showing how Milka deals with feeling tainted, through immersion into water as a form of purification after the traumatic experience.

Furthermore, Projansky identifies in film narratives “potential responses to sexual assault, each linked to women’s self-preservation in a context of gendered and sexualized oppression: run from it, ignore it, defend oneself from it and get revenge for it, and learn from and about it” (122). In the aftermath of the rape, Milka eventually leaves the godforsaken provincial town, that is, she runs from the memory of the harrowing sexual violence to which she was exposed. Her departure implies that she quit her job at the kiosk. Unlike Milka, Gordana in The Return does not quit her job, but they are both equally traumatised and silenced due to the devastating impact of gang rape. At first, Gordana does not confide in anyone about the hurtful experience she went through. She does not report the sexual violation to the authorities but represses the memory of it instead. Still, it affects her gravely. The extent to which the ordeal Gordana went through impacted her is demonstrated by a comment of a woman, addressed to Gordana’s father, that his daughter was drunk for two whole consecutive days. The woman begins to deliver this line in a two-shot that encompasses not only her, in the background in medium long shot, but also Gordana’s head in the foreground in medium close-up, as she lays in the bed, looking sideways, away from the woman. Gordana’s face is somewhat concealed by her hair, similar to Milka’s in Horoscope in the aforementioned multi-plane shot of the post-rape scene, so the facial expressions and feelings of raped heroines in both films are difficult to fathom, although the overall impression of severe despondence is conveyed. Gordana’s father attributes her withdrawn state to the New Year celebration. She remains silent throughout this brief scene. Later in the film, perhaps the most obvious manifestation of the trauma is that Gordana pulls away from courtly touch of Al Capone, the man she likes, whenever she is in his presence. Eventually, the consequences of the rape erupt out of her when she starts crying in his arms on one occasion, and only says vaguely: “They did...”, without further disclosing what happened to her. By witnessing in the denouement of the film the death of the man that she likes at the hands of the police, she loses the only person whose presence could have helped her overcome the trauma.

Even though Bigi, the main culprit of Gordana’s gang rape, is punished with incarceration for many years, he is not sentenced for the sexual violation, but for his other criminal behaviour, namely for a stabbing of a man. Although director Pavlović condemns the sexual violence towards Gordana, he simultaneously condones it by failing to give the gang rapists adequate punishment, or at least to pose the flagrant absence of any form of penalty for the gang rape as a problem. The situation in Horoscope is even more troubling because none of the youth clique members implicated in the gang rape face any consequences, except, ironically, for Vidak, who is wrongly killed by the police for the kiosk robbery that he did not commit. However, although he did not rape Milka because he had a change of heart, despite initially wanting to, his culpability lies in helping his peers to capture her and pin her down, as well as in his tacit complicity in his peers’ rapes of Milka. Like Gordana in The Return, Milka does not go to the police, so the gang rapes in both case study films remain unreported to the authorities and, thus, both heroines are silenced. Even though both Drašković and Pavlović give closure to their heroines, in the long run they do not empower them, nor offer them a chance to overcome the trauma, but instead turn them from independent into vulnerable women. To borrow from Danijela Beard’s observation, some Yugoslav New Films simultaneously “reinforce, as well as critique the wider social fear of strong women” (110).

Conclusion

One of the possible interpretations for the recurrent presence of the motif of rape in the Yugoslav New Film Movement is the reading of representations of gang rape as a cinematic patriarchal punishment for the real-life liberation of women. In films set in, at the time, contemporary socialist Yugoslavia, independent female characters, be it in terms of sexuality, work or otherwise, are made vulnerable by male sexual violence. In the selected Yugoslav New Films, directors simultaneously criticise sexual brutality towards women and endorse such violence due to their failure to address or penalise it accordingly. Both films were shot in black and white, but the styles and approaches to the representation of gang-rape scenes differed significantly. While Drašković explicitly shows the sexual abuse, Pavlović implies it. Although Drašković does not focus on Milka’s nudity during the gang rape, instead showing her terrified face whilst she gasps for air, he objectifies Milka during the struggle before the rapes. Also, Drašković fetishises her in the immediate aftermath of the rapes, by placing emphasis on her nude breasts. This feels exploitative considering the camera framing that fragments the female body into eroticised body parts, and the rape context in the narrative. By using Mulvey’s theory, Milka’s body throughout Horoscope is voyeuristically and fetishistically exhibited as a spectacle to be observed by the male characters, the proxies of the male director, via a camera operated by a man, and screened to the spectators, who are, consequently, invited to view with the male gaze, irrespective of their gender.

Contrary to Drašković, Pavlović does not sexually objectify Gordana’s body in an exploitative manner with camera framing or by choice of revealing clothing. Moreover, he does not show her nudity at all. Also, he gives insight into her trauma, by offering a female gaze via point-of-view shots, no matter how fleeting. However, it should be kept in mind that Pavlović occasionally exhibited rather chauvinist stances about women in his interviews and books. A frequent contradiction also present in other Yugoslav New Film auteurs, is to simultaneously contest and condone in their films the remnants of patriarchal stances towards women. When it comes to contesting sexual violence towards emancipated women, both directors address the post-rape trauma of the female characters. In Horoscope, Milka is shown cleansing in the river, that is, expressing corporeally her feelings of being soiled with rape, and later leaving the town for good. Similarly, in The Return, Gordana, besides resorting to alcohol for few consecutive days after sexual violation, recoils from the touch of the man she likes. On the one hand, Pavlović approximates the feelings of trauma to the audience by fleetingly offering Gordana’s subjective shots of the very football pitch where she was gang-raped and her flinching reaction to the players. On the other hand, Drašković somewhat keeps the spectators’ empathy at bay, by briefly showing Milka in post-rape situations, without offering the heroine’s point-of-view shots that would perhaps give deeper insight into her perspective.

Regardless of the many differences, both Drašković and Pavlović disempower female characters by rape, because they reduce them from emancipated employed women, who are free to choose and refuse their partners, to victims that do not overcome those hurtful experiences. What’s more, the perpetrators of the gang rapes are not adequately penalised. Namely, justice is served only to some extent in The Return, since although Bigi, the main perpetrator of the gang rape, is incarcerated, it is for his other crimes. Appallingly, in Horoscope the three gang rapists are not punished at all.

In conclusion, the female characters in question are emancipated working women, who reject men of a patriarchal mindset and consequently are punished by gang rape. This is in line with my interpretation that one of the possible readings of rape in Yugoslav New Film, specifically in the narratives set in their contemporary times, was that if women were modern, passionate or independent, eventually they would be exposed to violence for those transgressions against the remnants of the patriarchy. The ambiguous stance of directors Pavlović and especially Drašković towards their sexually violated female characters is in line with contradictions of Yugoslav society. Gender equality was legally promulgated in such a manner that nominally gave even more rights to Yugoslav women than to the women in the West, particularly in the public sphere. However, in the private sphere of the home and interpersonal relations, remnants of patriarchy occasionally lingered from the pre-socialist times and were hard to eradicate. The analysed films, perhaps inadvertently, produced warning messages to modern working women, who exercise freedom to choose and, more importantly, to refuse the suitors they encounter at the workplace.

Although I do not consider these films misogynistic, the directors used female characters’ gang rapes to their own means, to amplify their critique of society. From this, it can be deduced that they were not primarily interested in rape as dehumanising violence that strips a woman of her agency, nor in cautionary tales of punishment of rapists. Also, the impression is that, to some extent, Drašković condones Vidak, who, even though he refrained from raping Milka at the last moment, did not stop his friends from gang-raping her before it was his turn. I find these points problematic, as well as Drašković’s visual sexual objectification of Milka’s fragmented nude body parts in the context of the represented sexual abuse. Although both directors consider their heroine’s post-rape feelings and tend to show female rape as a negative issue, the films about rape of independent women can be read somewhere on the continuum between the critique of men’s brutal reaction to their independence and a cautionary tale which warns women that bad things would happen to them if they chose to live independently, leaning towards the latter. Bearing in mind that rape is a grave trauma for women, as evidenced for instance by the #MeToo movement worldwide, the directors, by simultaneously being resistant to and complicit in the represented gang-rape of independent female characters, inadvertently contributed towards fostering patriarchal practices, rather than promoting emancipatory ones. Female emancipation on screen was smothered in both films.

Notes

[1] The motif of female gang rape, or attempted gang rape, features in approximately fourteen feature fictional films, from my viewing of 269 films out of an estimated 286 made by Yugoslav directors between 1961-1972, encompassing both YugoslavNew Films, and (thematically and formally) mainstream films that coexisted with them.

[2] As kindly pointed out to me by Dr Nebojša Jovanović.

References

1. Anderson, Victoria. “Sins of Permission: The Union of Rape and Marriage in Die Marquise Von O and Breaking the Waves.” Rape in Art Cinema, edited by Dominique Russell, Continuum, 2010, pp. 69-82.

2. Beard, Danijela Š. “Soft Socialism, Hard Realism: Partisan Song, Parody, and Intertextual Listening in Yugoslav Black Wave Film (1968-1972).” Twentieth-Century Music, vol. 16, no. 1, 2019, pp. 95-121.

3. Bergstrom, Janet, and Mary Ann Doane. “The Female Spectator: Contexts and Directions.” Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies, vol. 7, no. 2-3 (20-21), 1989, pp. 5-27. https://doi.org/10.1215/02705346-7-2-3_20-21-5.

4. Boglić, Mira. Mit i antimit. Spektar, 1980.

5. Cahill, Ann J. “Boys Don’t Get Raped.” Rape in Art Cinema, edited by Dominique Russell, Continuum, 2010, pp. 113-28.

6. Clover, Carol J. Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton UP, 1992.

7. De Cuir, Greg Jr. Yugoslav Black Wave: Polemical Cinema from 1963-72 in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Film Center Serbia, 2011.

8. Gudac-Dodić, Vera. “Položaj žene u Srbiji (1945-2000).” Žene i deca: 4. Srbija u modernizacijskim procesima XIX i XX veka, edited by Latinka Perović, Zagorac, 2006, pp. 33-130.

9. Hamad, Hannah. “The Movie Producer, the Feminists and the Serial Killer: UK Feminist Activism, Misogynist 70s Film Culture and the (Non) Filming of the Yorkshire Ripper Murders.” Shadow Cinema: The Historical and Production Contexts of Unmade Films, edited by James Fenwick et al., Bloomsbury, 2021, pp. 235-50.

10. Haskell, Molly. From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies. 2nd Edition, The U of Chicago P, 1987.

11. Hofman, Ana. “When We Were Walking Down the Road and Singing.” Gender Politics and Everyday Life in State Socialist Eastern and Central Europe, edited by and Jill Massino Shana Penn, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009, pp. 185-97.

12. Horeck, Tanya. Public Rape: Representing Violation in Fiction and Film. Routledge, 2004.

13. Horoscope [Horoskop]. Directed by Boro Drašković, Bosna Film, 1969.

14. Jelača, Dijana. “Sasvim moguć optimizam: Žena i poslijeratni bosanski film." Komparativni postsocijalizam: Slavenska iskustva, edited by Maša Kolanović, Filozofski fakultet, Zagrebačka slavistička škola, 2013, pp. 311-29.

15. Jovanović, Nebojša. “Gender and Sexuality in the Classical Yugoslav Cinema, 1947-1962.” 2014. Central European University, PhD thesis.

16. ---. “Zazor od modernosti: Trauma ’68. i ‘sudar civilizacija’ u djelu Živojina Pavlovića.” Kriza i kritike racionalnosti: Nasljeđe ‘68, edited by Borislav Mikulić and Mislav Žitko, Filozofski fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, 2019, pp. 188-221.

17. Kaplan, E. Ann. Women and Film: Both Sides of the Camera. Routledge, 1990.

18. Kralj, Ana, and Tanja Rener. “Slovenia: From ‘State Feminism’ to Back Vocals.” Gender (in)Equality and Gender Politics in Southeastern Europe: A Question of Justice, edited by Christine M. Hassenstab and Sabrina P. Ramet, Palgrave Macmillan, 2015, pp. 41-61.

19. Leitch, Thomas M. Find the Director and Other Hitchcock Games. U of Georgia P, 2008.

20. MacDonald, Shana. “Materiality and Metaphor: Rape in Anne Claire Poirier’s Mourir À Tue-Tête and Jean-Luc Godard’s Weekend.” Rape in Art Cinema, edited by Dominique Russell, Continuum, 2010, pp. 55-68.

21. MoMA. “Contemporary Yugoslav Cinema: First Time in USA.” The Museum of Modern Art, 12 Nov. 1969, pp. 1-5, www.moma.org/docs/press_archives/4371/releases/MOMA_1969_July-December_0064_140.pdf.

22. Moore, Michelle E. “‘If It Was a Rape, Then Why Would She Be a Whore?’ Rape in Todd Solondz’ Films.” Rape in Art Cinema, edited by Dominique Russell, Continuum, 2010, pp. 129-44.

23. Morokvašić, Mirjana. “Being a Woman in Yugoslavia: Past, Present and Institutional Equality.” Women of the Mediterranean, edited by Monique Gadant, Zed Books, 1986, pp. 120-38.

24. Mulvey, Laura. Fetishism and Curiosity. British Film Institute, 1996.

25. ---. Visual and Other Pleasures. 2nd Edition, Palgrave, 1989.

26. Novaković, Slobodan, and Bogdan Tirnanić. “Živojin Pavlović: Istina umesto ‘lepote’!” Polja, vol. 109, no. XIII, 1967, pp. 4-6.

27. Pavlović, Živojin. Đavolji film: Ogledi i razgovori. Institut za film, 1969.

28. Petrović, Aleksandar. Novi film II (1965-1970): “Crni film”. Naučna knjiga, 1988.

29. Projansky, Sarah. Watching Rape: Film and Television in Postfeminist Culture. New York UP, 2001.

30. Radić, Damir. “3. Subversive Film Festival-Retrospektive jugoslovenskog filma 1955-1990: Povijesne poslastice i otkrića.” Hrvatski filmski ljetopis, vol. 63, no. 16, 2010, pp. 94-105.

31. Ramet, Sabrina P. “In Tito’s Time.” Gender Politics in the Western Balkans: Women and Society in Yugoslavia and the Yugoslav Successor States, edited by Sabrina P. Ramet, The Pennsylvania State UP, 1999, pp. 89-106.

32. Ranković, Milan. Seksualnost na filmu i pornografija. Prosveta, Institut za film 1982.

33. The Return [Povratak]. Directed by Živojin Pavlović, Avala Film, 1966.

34. Slapšak, Svetlana. “Representations of Gender as Constructed, Questioned and Subverted in Balkan Films.” Cinéaste, vol. 32, no. 3, 2007, pp. 37-40.

35. ---. “Žensko telo u jugoslovenskom filmu: Status žene, paradigma feminizma.” Žene, slike, izmišljaji, edited by Branka Arsić, Centar za ženske studije, 2000, pp. 121-38.

36. Smelik, Anneke. And the Mirror Cracked: Feminist Cinema and Film Theory. Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

37. Tirnanić, Bogdan. “Kamerom kroz polusvet: U znaku device.” Jež, no. 1577, 19 Sep. 1969, p. 21.

38. ---. “S one strane brda... Ili: Još jedna mogućnost ponovnog pristupa ‘Horoskopu’.” Odjek, vol. XXIII, no. 9-10, May 1970, p. 18.

39. The 39 Steps. Directed by Alfred Hitchcock, Gaumont, 1935.

40. Two Women [La Ciociara]. Directed by Vittorio De Sica, Compagnia Cinematografica Champion, 1960.

41. Ugrešić, Dubravka. “Jer mi smo dečki.” Kruh i ruže, no. 1, Spring 1994, haw.nsk.hr/arhiva/vol1/802/881/www.zinfo.hr/hrvatski/stranice/izdavastvo/kruhiruze/kir1/1decki.htm. Accessed 3 July 2023.

42. Vincendeau, Ginette. “Crossing the Line: Against.” Sight & Sound, vol. 27, no. 4, 2017, p. 33.

43. The Virgin Spring [Jungfrukällan]. Directed by Ingmar Bergman, Svensk Filmindustri, 1960.

44. Williams, Linda. Screening Sex. Duke UP, 2008.

Suggested Citation

Vuković, Vesi. “Freedom Smothered: Gang Rape as Patriarchal Punishment of Emancipated Women in Yugoslav New Film.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 25, 2023, pp. 40-60. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.25.03

Vesi Vuković holds a Doctorate in Film Studies and Visual Culture (University of Antwerp). She is a voluntary postdoctoral researcher at ViDi (Visual and Digital Cultures Research Center) of the University of Antwerp. She attained her Master of Arts at Kyoto University of Arts and Design, Japan. Her current research focuses on ex-Yugoslavian cinema and its representation of women. She has published articles in the journals Studies in Eastern European Cinema (2018; 2022), Apparatus: Film, Media and Digital Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe (2019), and Images: The International Journal of European Film, Performing Arts and Audiovisual Communication (2020), as well as a chapter in the edited collection Balkan Cinema and the Great Wars: Our Story (2020).