Re-imagining Multiculturalism and Diversity Through Screenwriting and Filmmaking

Vincent Giarrusso

Abstract

This paper explores pedagogic methods used in the research project “Zooming In: Multiculturalism Through the Lens of the Next Generation”. The project is a reimagining of multiculturalism and diversity through filmmaking and sociology. An important component of this research are the films produced in association with the Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC), which contribute to a narrative of inclusion and diversity. The process of screenwriting and development, then filmmaking, is conditional around individual agency and the mediation of practice in the generation of the screen idea (Millard, Screenwriting). Researchers such as Craig Batty, Susan Kerrigan, Ian W. McDonald and Kathryn Millard direct research attention to the practices of screenwriting as matrixes that offer a structure or logic to the screen idea. The outcome of screenwriting practice requires a pedagogic and andragogic design that recognises and engages with complex functions and meanings. The paper approaches writing for the screen as a set of interconnected regularised activities, examining the dynamic interplay between the subjective experience of the practitioner and the rules and expectations of the institutions involved.

Dossier

Figure 1: Wishing Tree (Alex Nesic, 2019). Student film. Screenshot.

Australia’s demography and migration patterns have undergone significant change since multiculturalism was introduced as the national settlement policy over forty years ago. The current generation sees cultural diversity, inclusion and multiculturalism in different ways to those who encountered them in the significantly different social context of their introduction. In contrast to earlier generations, young adults today have grown up within a society characterised by high levels of ethnic diversity and fluid identity. Education design and method should reflect this fundamental characteristic of fluidity and variance.This paper takes key teaching principles from Murray Print, Shirley Grundy, and Sharan B. Merriam (“Adult Learning”) to examine the dynamic interplay between the subjective experience of the student film practitioner and the rules and expectations of the institutions involved in developing and writing for the screen. It interrogates institutionalised practices of pedagogy as they are exchanged for a fluid andragogic approach. This interrogation is influenced by the work of Ian W. McDonald, Susan Kerrigan and Craig Batty, and Kathryn Millard who have advocated and expanded on a screen development method known as the “screen idea”.

Background

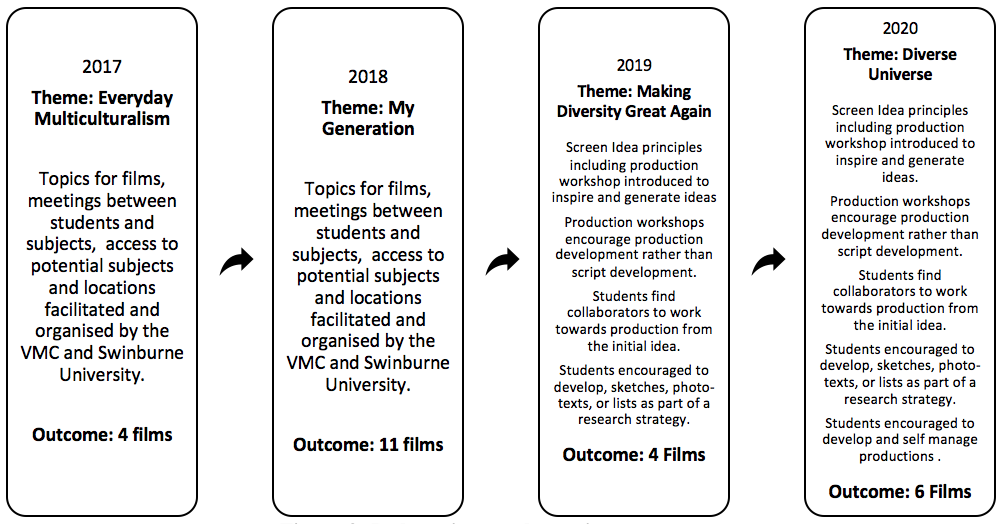

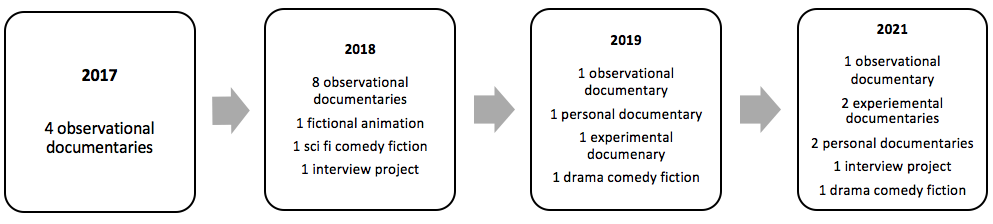

The paper uses the research project “Zooming In: Multiculturalism Through the Lens of the Next Generation”as a representative case of this approach. “Zooming In” is a collaborative research project between Swinburne University of Technology and the Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC) that uses film and sociology to generate new perspectives on multiculturalism from the perspective of young people. My pedagogical involvement in the project over the course of five years has given me background information, affording a unique insight into underlying intentions, requirements and outcomes of the development process. In the first two years of the project, the VMC and Swinburne were prescriptive in how topics and subjects for films were developed. Development of the projects were structured around a set of interconnected regularised activities that followed the rules and expectations of the institutions involved. At first this approach was pedagogical in that both the VMC and Swinburne were operative in helping the students find subjects and instigating development and production. The resulting outcomes for the first two years were a total of fifteen films, twelve of which were observational documentaries. The observational documentaries were of notable community members which were characterised by standardised filmmaking techniques and narrative structures.

In the first two years, institutional processes enabled students to master a style of development through an understanding of industry-based protocols and expectations. Through this process, students learnt that social instituting and structure define a type of learning and that there is an extrinsic component in practice that is linked to a result-driven task which is vocational. Embedded in the significance of the institutional screen practices is acknowledgement of its diverse functions and status as an object per se. This traditional knowledge of the practices for the screen has been built upon over time and has historical amplitude.

Figure 1 outlines the themes used to encourage the development of ideas and generate screen production across the first four years of the project, the modes of engagement with the student filmmakers and the subsequent outcomes.

Figure 2: Pedagogic to andragogic engagement.

In the following two years, the teaching method moved to an andragogic mode of self-directed and autonomous learning. This was initiated by introducing the “screen idea” as developed by scholars such as Ian W. McDonald, Susan Kerrigan, Craig Batty and Kathryn Millard and used as a development tool. The “screen idea” encourages development through collaborative research working towards production practices that privilege the transitional state of creativity at the threshold of writing and production. Different forms of scripting and development are encouraged, including “map, sketches, photo-texts, a wiki, a list, scenes that form part of a jigsaw, a graphic novel, a video trailer, a short film—whatever works” to open up the creative potential of the students (Millard, Screenwriting 303).

Development was steered away from overly familiar ways of doing things and towards a “freedom from predictive and structuring tools” (Senje 281). From the outset, a self-reflexive instinct was evident in the choices that the student filmmakers made. This approach was interconnected with an exploration of major life events of the student filmmakers. The personal migrant narrative figured prominently in the films being developed at this time. The tension between the screen idea, modes of production and habitus reflect a creative practice that considers habitus as a defining feature and indicates a “capacity for invention and improvisation” (Bourdieu 13).

The constraints of the programme—imposed, incidental or accidental—within the “screen idea” model were embraced rather than challenged. The outcome of this shift in the next two years of production were a total of ten films, of which only two were traditional observational documentaries (Fig. 2). The remaining films took a more personalised and unconventional approach to filmmaking, including experimental documentaries and deeply personalised explorations of diversity and inclusion.

Figure 3: Content outcomes.

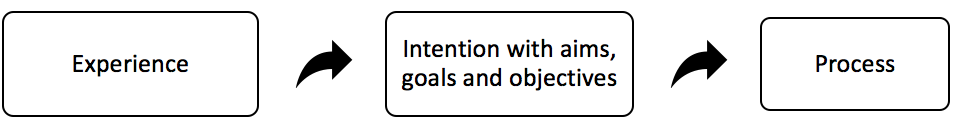

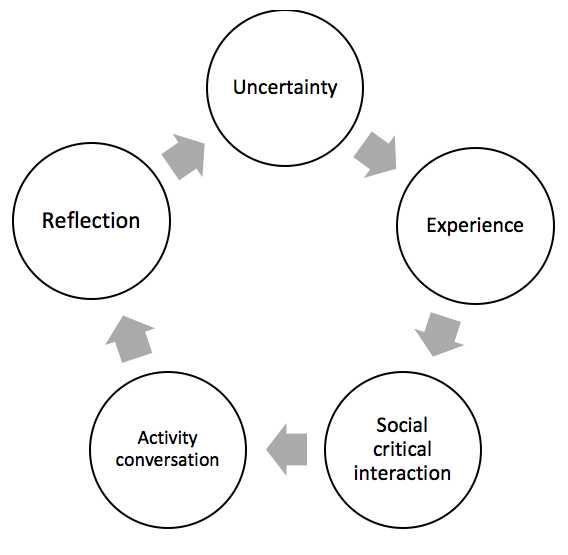

The significant benefits to students’ experience and learning outcomes was that the andragogic approach to research was structured as experience, defined by a set of planned and unplanned learning experiences encountered by the students. The shift also prompted critical thinking skills beyond the screen content (Merrian, “Adult Learning” 35). The andragogic objective was characterised by aims, goals and intent which were process driven, emphasising personal growth and self-actualisation through experiential learning as defined by Print (Fig. 3). It was important that students wrote from their place and their own personal experience, reflecting situational content, analysis and evaluation.

Figure 4: Research as experience (Print).

Transitional Learning in Liminal Space

The process used to support the student cohort assumed that the students are adult learners (Merriam, “Adult Learning”). This distinction was important in that it acknowledged both a theoretic and practical approach to screen practices that was self-directed and autonomous with teachers as facilitators of learning. The motivation to creative practice was driven by internal factors such as self-actualisation and self-confidence.

In the second two years, students’ creative practice explored narrative and character in an intrinsic fashion, focusing on personal experiences and history while developing themes and storylines in a collaborative way. This was fostered by a shift away from institutional practices. Self-reflective practice was encouraged to balance outcomes between inherent intrinsic and extrinsic functions, raising critical questions around multicultural storytelling. For example, students were encouraged to keep journals of process and document the development path of their project through audio recordings of meetings and interactions. Self-reflexivity refers to the consciousness of the ongoing circular relationship between the things we experience as we experience them.

Students were also encouraged to report progress to instructors on a regular basis. Self-reflexivity in this instance is linked closely to the paradigm of cause and effect. Self-reflexivity can be defined as reasoning against the criteria of comprehensibility, truth and accuracy. It is guided by an emancipatory interest in identifying and overcoming incomprehensibility, irrationality and injustice (Habermas). Self-reflexive practice considers that practice is not just activity; it also involves meaning and intention. Self-reflection could also recognise that artistic actions may be a response to a complex set of situations.

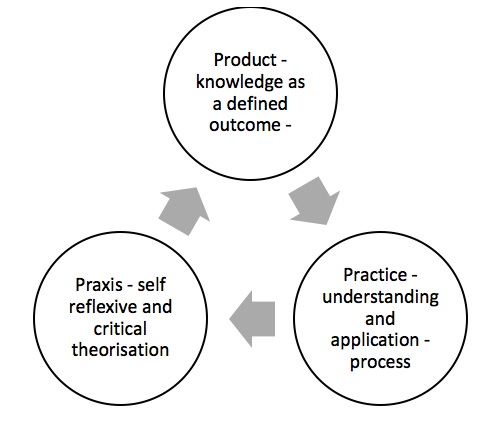

The emphasis in this approach was on practice, praxis and product (the content created), reflecting the facilitation of critical thinking within a quasi-experimental design (Grundy). This engagement is based on three rationales: the outcome (product), where the focus is on reproducing knowledge for an undefined outcome in the “doing” (practice) that emphasises the development of understanding to make judgements and apply knowledge, and in praxis where the focus is on critical reflection with outcomes determined by the students and centred around self-assessment and critical analysis (Fig. 4).

Figure 5: Product and praxis (Grundy).

The transition from pedagogic to andragogic engagement taps into the liminal spaces where processes inherent in generation of creative practice are manifest.

The “screen idea” gives prominence to individual agency and the mediation of practice (Millard, Screenwriting). Researchers such as Kerrigan, McDonald and Millard direct attention to the liminal aspects of screen development and screenwriting practice, suggesting that they are matrixes that offer structure or logic. Adrian Martin suggests that the “distinctions between properly cinematic ideas, less cinematic ideas and non-cinematic ideas” (16) are a rich source of information that can help chart how an idea for the screen is “articulated, expressed, nurtured and developed” (17). This logic applied to development in the context of student filmmaking results in a rich stream of instruction and interaction.

Outcomes

What are the outcomes, besides the films themselves, of this shift in teaching approach? The inherent outcomes suggest a post-positive model of andragogic determinations that are instrumental in generating outcomes that reflect the experience of the student. Rather than focus on the material outcomes inherent in the process (as outlined in Fig. 3), I suggest the following educative outcomes that contributed to the student experience (Fig. 5).

Figure 6: Post-positivism model of learning outcomes.

Reflection in this context can be “understood as an enhanced perception and cognitive ability—one in which reconsideration, consultation with self, recapitulation and self-criticism blend with insights largely stimulated through confrontation” (Murray 191).

Conclusion

The intention of this paper was to interrogate education frameworks that contribute to the ongoing and fluid narrative of inclusion, diversity and multiculturalism from the perspective of a younger generation. The shift from pedagogic teaching method to an andragogic mode of self-directed and autonomous learning resulted in content that reflects the characteristics of fluidity and variance that are part of the worldview of young filmmakers. The methods used in the “Zooming In” project empower young filmmakers to create representations of vibrant multicultural communities that are not only visual celebrations of cultural diversity but also suggest the potentialities of social cohesion.

References

1. Bourdieu, Pierre. The Logic of Practice. Translated by Richard Nice, Stanford UP, 1990.

2 Brookfield, Stephen D. The Power of Critical Theory: Liberating Adult Learning and Teaching. Jossey-Bass, 2005.

3. Dawson, Phillip, et al. “What Makes for Effective Feedback: Staff and Student Perspectives.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, vol. 44, no. 1, 2019, pp. 25–36. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877.

4. Grundy, Shirley. Curriculum: Product or Praxis. Falmer, 1987.5. Habermas, Jurgen. Theory and Practice. Translated by John Viertel, Heinemann, 1974.

6. Kerrigan, Susan, and Craig Batty. “Looking Back in Order to Look Forward: Re-scripting and Re-framing Screen Production Research,” Journal of Australasian Cinema, vol. 9. no. 2, 2015, pp. 90–92. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/17503175.2015.1060010.7. Kerrigan, Susan. “The Spectator in the Film-maker: Re-framing Filmology Through Creative Film-making Practices.” Journal of Media Practice, vol. 17. no. 2–3, 2016, pp. 186–98.

8. MacDonald, Ian W. Screenwriting Poetics and the Screen Idea. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

9. Martin, Adrian.“Where Do Cinematic Ideas Come From?” Journal of Screenwriting, vol. 5, no. 1, 2014, pp. 9–26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.5.1.9_1.

10. McIntyre, Phillip. “Constraining and Enabling Creativity: The Theoretical Ideas Surrounding Creativity, Agency and Structure.” The International Journal of Creativity and Problem Solving, vol. 22. no. 1, 2012, pp. 43–60.

11. Merriam, Sharan B. “Adult Learning Theory: Evolution and Future Directions.” Contemporary Theories of Learning: Learning Theorists ... in Their Own Words, edited by Knud Illeris, Routledge, 2018, pp. 83–97.

12. ---. “Adult Learning Theory: Evolution and Future Directions.” PAACE Journal of Lifelong Learning, vol. 26, 2017, pp. 21–37.13. Millard, Kathryn. Screenwriting in a Digital Era. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

14. ---. “The Universe is Expanding.” Journal of Screenwriting, vol. 7. no. 3, 2016, pp. 271–84. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.7.3.271_3.

15. Murray, Louis. “What is Practitioner Based Enquiry?”, British Journal of In-Service Education, vol. 18, no. 3, 1992, pp. 191–96. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/0305763920180309.

16. Print, Murray. Curriculum Development and Design. Allen and Unwin, 1993.

17. Senje, Siri. “Formatting the Imagination: A Reflection on Screenwriting as a Creative Practice.” Journal of Screenwriting, vol. 8, no. 3, 2017, pp. 267–85. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1386/josc.8.3.267_1.

Suggested Citation

Giarrusso, Vincent. “Re-imagining Multiculturalism and Diversity Through Screenwriting and Filmmaking.” Dossier: “Addressing Diversity On and Off Screen in the Classroom”, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 24, 2022, pp. 160–67. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.24.11

Vincent Giarrusso lectures in writing for screen and direction with an emphasis on the social and cultural significance of filmmaking. Vincent successfully submitted his PhD in 2018. Vincent co-runs a research project with the Victorian Multicultural Commission, “Zooming In: Multiculturalism Through the Lens of the Next Generation”,which uses film and sociology to generate new perspectives on multiculturalism and diversity. Vincent’s film Mallboy (2000), which he wrote, directed and composed music for, was selected for Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes. He is an ARIA award winning and Australian Music Prize musician and recent work was nominated for AMCOS/APRA Australian Song of the Year 2019.