White Noise: Researching the Absence of First Nations Presence in Commercial Australian Television Drama

Karen Nobes and Susan Kerrigan

[PDF]

Abstract

First Nations content on commercial Australian television drama is rare and First Nations content makers rarely produce the content we see. Despite a lack of presence on commercial drama platforms there has been, and continues to be, a rich array of First Nations content on Australian public broadcast networks. Content analysis by Screen Australia, the Federal Government agency charged with supporting Australian screen development, production and promotion, aggregates information across the commercial and non-commercial (public broadcasting) platforms which dilutes the non-commercial output. The research presented in this article focused on the systemic processes of commercial Australian television drama production to provide a detailed analysis of the disparity of First Nations content between commercial and non-commercial television. The study engaged with First Nations and non-Indigenous Australian writers, directors, producers, casting agents, casting directors, heads of production, executive producers, broadcast journalists, former channel managers and independent production company executive directors—all exemplars in their fields—to interrogate production processes, script to screen, contributing to inclusion or exclusion of First Nations content in commercial television drama. Our engagement with industry revealed barriers to the inclusion of First Nations stories, and First Nations storytelling, occurring across multiple stages of commercial Australian television drama production.

Article

Introduction

In 2022, Australia’s longest running soap opera Neighbours (1985–2022) was cancelled when the UK broadcaster did not renew the contract (Boaz). Although the decision was framed in economic terms, criticism of the programme for its almost exclusively white cast and, more recently, complaints of episodes of racism on set had become harder to ignore (“Neighbours”). As noted by Andrew Jakubowicz in 2010, the “streets of Neighbours and Home and Away remained blandly Anglo, with an occasional and often violently resented non-White newcomer” (1). Australian culture, as represented in Neighbours, was broadcast to more than sixty countries worldwide for thirty-seven years. The absence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) content “means something and signifies as much as presence” (Hall 16).[1] Aileen Moreton-Robinson, an Indigenous Elder and professor at RMIT in Melbourne, argues that “normativity and invisibility of whiteness and its power within the production of knowledge and representation” in Australia is evident in the resolutely white content of commercial television drama screens (“Whiteness” 75).

These comments amount to say that commercial TV as a powerful cultural resource is complicit in manufacturing consent for white Australian creation stories which perpetuate a law from 1788 of “terra nullius”, used by the British to describe Australia as a land legally deemed unoccupied or uninhabited—“nobody’s land”. Terra nullius is a concept that continues to nullify the existence of First Nations peoples because of “[t]he systematic exclusion of Aboriginal peoples from equal participation in Australian culture, reflected and perpetuated through mainstream media representation” (Meadows 50). Although recent successful dramas featuring First Nations writers, producers, directors and actors have been awarded, applauded and are responsible for an increase of First Nations content on Australian small screens, this content exists almost exclusively in the non-commercial space (Nobes 4).[2] The 2016 Screen Australia report “Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in TV Drama”, the organisation’s first report on diversity, found that five percent of main characters in Australian TV drama are First Nations, despite accounting for only three percent of the population (6). The story behind the statistics makes a clearer commentary on the state of representation in TV broadcast. The statistics are significantly bolstered by ATSI characters appearing in eight programmes, all of which were broadcast on the publicly funded Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC).[3] By aggregating content across the commercial and non-commercial sectors, the Screen Australia report ignores the enormous disparity between the amount of First Nations content on the publicly funded platforms (ABC, Special Broadcasting Services and National Indigenous Television) as compared to that of the commercial platforms (Networks 7, 9 and 10).

Framed by theories of postcolonialism, whiteness and identity (Kowal; Langton and Bowers; Moreton-Robinson, “I”, “Whiteness”, and Whitening; O’Dowd), as well as drawing on theories of structures and practices of media industry and creativity (McQuail and Deuze; Csikszentmihalyi; Redvall), the research that will be presented in this article sought to answer the question, “How does commercial television drama production perpetuate a cultural terra nullius?” (Nobes 30). The data was collected between 2016 and 2019 for White Noise, a creative practice exegesis and documentary doctoral project (Nobes). Informal and in-depth interviews were filmed with fourteen First Nations and White Australian drama and screen practitioners. Emerging from the theoretical mapping of the interview data were a number of themes around the entrenchment and manifestation of postcolonising structures that resulted in identifying choices, enacted through an elite group of decision makers, that have affected the selection and visibility of First Nations drama content in Australian commercial TV. Karen Nobes’s research findings labelled the themes emerging from these creative practices in commercial TV drama as “the medium is the message”, “white power”, “casting”, “colour-blind casting” and “the right to write”. These themes established terms, language, practices and interactions as sites of contestation by directly connecting the creative production systems for Australian scripted drama processes to postcolonialising behaviours.

Whiteness, Colonialism or Postcolonialism and First Nations Stories

“Whiteness” is defined as a Western construct, “an invisible regime of power that secures hegemony through discourse and has material effects in everyday life” (Moreton-Robinson, “Whiteness” 75). The term “White” refers to a social category and not a skin colour (Kerrigan 4; Kowal 340) and, in the Australian context, is used to define those who “participate in the racialized societal structure that positions them as ‘White’ and accordingly grants them the privileges associated with the dominant Australian culture” (Kowal 341). The invisibility of whiteness, structural racism and discursive practices are as insidious as the foundation lie of terra nullius. These discourses spill into the media and screen industries. The oppressive practices of racism reside in our social and political systems and, by extension, are found within the media systems that culturally represent contemporary Australian society (McQuail and Deuze). While Australian sociologists argue that substantive progress has been made “in the social and political reclamation of Indigenous rights”, there continues to be an enduring and “powerful sense of colonisation” (Saunders 56). Critical discourse, presented from a settler colonial studies perspective, points out that colonialism should be seen as “a structure not an event”; that is, colonialism continues to be experienced (Te Punga Somerville 279). Colonialism is part of the social and cultural fabric of colonised countries and, as Moreton-Robinson argues, Australian colonialisation has “material effects in everyday life” (“Whiteness” 75).

A state of postcolonisation can only be achieved once colonialism has passed “and the group of people once subjugated to the control of imperialism have achieved sovereignty, self-determination and political recognition” (Saunders 56). In Australia, there is a misleading suggestion that colonialism is over, but, as Saunders argues, “it would be inaccurate to describe Australia as a post-colonial nation” (59). This confusion is visible in Marcia Langton’s influential study, Well I Heard it on the Radio and I Saw It on the Television (1993), which contextualises “Aboriginality” as a postcolonising White construct. Challenging the notion of Australia as a postcolonial state, Moreton-Robinson argues, First Nations ontological belonging to the land “is omnipresent and continues to unsettle non-Indigenous belonging based on illegal dispossession” (“I” 24). In Australia, Aboriginal sovereignty has not been legally recognised (Kowal; Saunders), and Aboriginal identity has a faint presence in contemporary Australian law (Morgan). Drawing on this sociological perspective, and the position taken by settler colonial studies, the absence of political and legal recognition also structurally underpins the denial of First Nations peoples and their stories.

Decades of First Nations Screen Research

The significant absence of First Nations content on commercial Australian TV drama has been researched from a media studies perspective using contemporary theories of identity, culture and representation (Hall; Thornham and Purvis; Bostock; McKee). The lack of visibility of First Nations people on Australian Screens connects to literature on Whiteness and identity, and the perpetuation of White Australia (Moreton-Robinson, “I”, “Whiteness”, and Whitening; Bostock; Langton and Bowers; McKee; Harrison). This construction of identity through Whiteness covers concepts of representation, subjectivity, nationalism and the law (Delgado and Stefancic; Allen; Dyer; Frankenberg). Important contributions to the discussion include Harvey May’s work (Broadcast; “CulturalDiversity”). A decade ago, Jakubowicz noted “a crisis of recognition of diversity in public culture in Australia, one which gnaws at the heart of the country. It is racism at its most systematic, unselfconscious and destructive” (1). These arguments have been carefully constructed and socially translate to an Australian identity that continues to exclude First Nations people (O’Dowd 32).

“Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in TV Drama”analysed the diverse heritage of scripted drama through 199 programmes and found that only thirty-three had First Nations main characters, resulting in eighty-three percent of Australian programmes having “no Indigenous main characters” (11). This was the highest result amongst all the diversity categories. As already mentioned, First Nations characters were concentrated in eight programmes, all of which were broadcast on the publicly funded ABC (12). The 2016 Screen Australia report on diversity does show the significant improvement in First Nations participation as content creators and actors, particularly in non-commercial spaces. However, a closer analysis shows the lack of progress made in commercial scripted drama, and it was the unhurried pace of change occurring in the commercial sectors which motivated this research.

Researching White Noise

The aim of Nobes’s doctoral research was to make the documentary White Noise using a practice-led approach (as defined by Hazel Smith and Roger Dean) to explore the production processes contributing to either the presence or the absence of First Nations content in commercial TV drama. A series of in-depth interviews, with exemplars in the field, was the primary means of data collection. Research participants were recruited to discuss their professional practices and personal experiences of First Nations participation in commercial drama. This research design had some limitations, and most importantly that everyone participating would be discussing the topic on camera, therefore anonymous contributions could not be accommodated. Also, there was the possibility that, during the research, one of the long-running soap operas, Home and Away or Neighbours, may cast a First Nations character with a First Nations backstory; or that commercial networks might commission a drama created by First Nations creatives. However, throughout the research period none of these things occurred.

A purposive sampling technique was used to yield insights through “information-rich cases” (Bloomberg and Volpe 104). Snowball sampling ensured the widest net was cast (Marshall). This was done using personal invitations to gain access to high-profile drama creatives. Selection of research participants was based on two criteria: participants who had specific experiences or participants with special expertise. Appropriate ethical approvals were secured so the research participants could be identifiable to meet professional documentary standards. Seventy-five individuals were approached to participate: forty-five First Nations creatives and thirty non-Indigenous, with a gender mix of thirty-five women and forty men. Negotiations involved fifteen artist agencies, five advertising agencies and twenty-four agents and personal assistants. These negotiations resulted in the selection of fourteen interview participants. The timing of the interviews frequently eliminated potential First Nations candidates due to scheduling conflicts. Of the fourteen creatives who participated, four identified as Aboriginal and one as a Torres Strait Islander. All participants worked in film and TV drama production or as expert specialists in First Nations media.

The interviewees included producer, writer and actor Tony Briggs and producer-director John Harvey, who have worked in the film and TV domain locally and internationally; Susan Moylan-Coombs, who worked in senior roles at ABC and NITV; Tanya Denning-Orman, currently NITV channel manager; Jack Latimore, managing editor of NITV digital and Indigenous affairs journalist at The Age; producer, executive director and showrunner Tony Ayres and high-end drama producer Helen Bowden, who were also founding members of Matchbox Pictures; Robert Connolly, from Arenafilm, one of Australia’s most successful film and TV directors and producers; casting director Anousha Zarkesh, who has cast innumerable successful productions including The Secret Daughter (2016–17) (Screentime), Redfern Now (2012–15)(Blackfella Films), Mabo (2012) (ABC/Blackfella Films), Cleverman (2016–17) (ABC) and Black Comedy (2014–18) (Scarlett Pictures). Also interviewed were literary agent and former actor’s agent Jennifer Naughton, co-owner of one of Australia’s foremost artist representation companies, the RGM Artist Group; screenwriters and showrunners Kristen Dunphy and Vanessa Alexander, both with national and international drama writing credits; and investigative journalist Mark Bannerman, who has worked in commercial and non-commercial TV. Renowned film auteur Rolf de Heer also contributed, with the caveat that his area of interest and expertise was in film and not TV.

Figure 1: Producer, director and writer John Harvey, who features in the research as a participant. Still from White Noise by Karen Nobes, doctoral film (2022).

Nobes’s professional career as a TV director and producer underscored the practice-led methodology. The research participants were filmed and the responses edited against themes arising from the literature on whiteness and cultural identity. The critical analysis deconstructed Australian TV drama processes for scripted content to “illuminate and understand complex psychosocial issues in a site of creative, cultural production” (Nobes 38). As Norman Blaikie argues, “social regularities can be understood, perhaps explained, by constructing models of typical meanings used by typical social actors engaged in typical courses of action in typical situations” (48). Further analysis was undertaken using a creative systemic framework (Csikszentmihalyi; Redvall). This led to a finding that illustrates how limitations occur within the creative system and hence the Systems Model of Creativity (Csikszentmihalyi) was specifically adapted to reflect the Australian television drama context by mapping the ways in which advances in First Nations content and creation are being stymied in the commercial sphere.

Mapping the Systemic Nature of Australian Commercial TV Drama Production

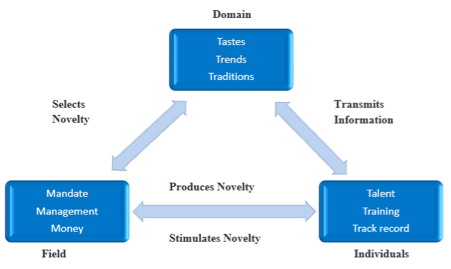

The commercial drama commissioning processes were mapped against a creative system (Csikszentmihalyi) and re-interpreted through Eva Novrup Redvall’s “Screen Idea System” (Fig. 1).

Figure 2: The Screen Idea System. Based on Eva Novrup Redvall (31).The Screen Idea System unpacks three components of decision-making processes that contribute to the creation of a screen idea. At a very practical level it reveals how doors are opened or closed to First Nations drama content. The Screen Idea System is comprised of the “domain” of knowledge consistent with the tastes, trends and traditions of an archive of First Nations screen content. A “field” of experts act as gatekeepers to provide admission to the domain or archive based on their intimate understanding of the domain. As managers they exercise their power to recreate the social structures by controlling the money and endorsing, or choosing not to endorse, a First Nations mandate. The “individuals” or agents represent First Nations creatives, who are filmmakers or actors who have the talent, training and track record to convince the managers (field experts) that their ideas are novel and worth commissioning. Screen ideas that are worth commissioning should eventually be deposited, as First Nations screen stories, in the domain. The creative system artificially separates the structural components of creativity into culture and society while accommodating how agents make novel choices by internalising social and cultural practices (Csikszentmihalyi 314–16). This manipulated extrapolation of the creative system makes it possible to see the postcolonialising structures being enacted systemically to support or constrain First Nations creatives and their screen works. By providing a postcolonialising analysis, the research identifies barriers to commissioning commercial First Nations drama content. To see how this oppression manifests and is experienced through these postcolonialising structures, we have defined the nature of each domain, field and individual/agent for this research context.

The Domain: Television Scripted Drama

Television drama commissioning and production was the domain for this doctoral research. The domain is defined as a cultural archive of a set of symbolic rules and procedures (Csikszentmihalyi 318); these are stored as the codes and conventions inside Australian TV episodes and series. A domain is scalable and can be international or local, depending on the cultural archive being examined. For this study, the sub-domains consist of commercial and/or non-commercial TV drama, both of which include First Nations dramas. This domain overlaps with the broader cultural archive of First Nations artistic works from dance, literature, theatre and cinema, which are relevant because they showcase the phenomenal advances by Indigenous creatives, particularly across the past few decades. All First Nations screen works are included in the domain because they set the tone and standard of First Nations screen content. Each new First Nations work that enters the domain has the potential to change the makeup of that domain (Fulton 45)—although they enter the domain one film at a time.

Another significant example of what exists in the domain for television drama is the substantial body of First Nations drama content made at the ABC. In 2010, the ABC established an Indigenous Department to “develop and commission an expanded slate of prime-time Indigenous drama and documentary” (“Seeing” 12). Sally Riley, a Wiradjuri woman, joined as Head of Scripted Production. Formerly Head of Indigenous at Screen Australia, Riley enacted a strategy “to develop skills in the Indigenous film-making sector so they can cross over on to the small screen” (Rourke). Redfern Now was the first TV drama commissioned, written, acted and produced by Indigenous Australians (Rourke). Other works that were part of that strategy were Mabo, Gods of Wheat Street (2013–14), 8MMM Aboriginal Radio (2015), Cleverman, The Warriors (2017), Black Comedy and Mystery Road (2018–). Some of these programmes have been sold internationally on streaming platforms, with Redfern Now seen as a turning point for the television industry. Riley explains the ABC was “providing the finance and infrastructure for real career opportunities for creative Indigenous Australians, which is very exciting. This contribution to the industry will hopefully have an amazing impact for years to come” (qtd. in Delaney). This ABC programmes visibly changed the domain of First Nations screen content, while across the same period there were limited offerings from the realm of commercial drama, although long-form soap operas comprised forty-two percent of Australian drama production (Lotz and Sanson 19).

The Field: Mandate Through Policy, Charter and Ratings

As described, the field consists of the managers and gatekeepers who commission television content in Australia, and consequently have the mandate and the money to select content that will satisfy policies, regulations, business and creative strategies. Field members are powerful because they decide whether a new idea, product or individual should be included in the domain (Csikszentmihalyi 324–5). For this project, field members exercise their commissioning power over all scripted dramas. Operating in a complex network of policies, regulations, finances, ownership, distribution platforms and business structures, these field members’ choices, practices and conduct are influenced by the “methods of selecting and producing content, editorial decision making [and] market policy” (McQuail and Deuze 203).

In Australia, all the field members are working under government regulations, e.g. theBroadcasting Services Act 1992, which outline the medium’s public influence and power and the role that it plays “in promoting Australians’ cultural identity” (Australian Government 65). During the research period, the commercial networks had to comply with an Australian content quota, which included a sub-quota for commissioning drama productions. Scholars believe that these sub-quotas artificially affected the scripted drama made in Australia, however they were altered in 2020 (Lotz and Sanson 9). It is important to note that the ABC and SBS do not have to comply with drama sub-quotas because they are publicly funded.

Another structure affecting preferences of field members are TV ratings that rely on an older advertising business model. This model is being superseded with subscription video-on-demand platforms (SVOD). Commercial networks rely heavily on ratings figures and high or low ratings can determine a programme’s future. The ABC is not immediately affected by low ratings. Ratings agencies such as OzTam gather their statistics primarily from urban white audiences (Neilson); rarely they include a breakdown of ethnicity of audiences in their reports. The institutional and structural set-up of commercial ratings is an example of a postcolonialising structure where power discourses (as defined by Robert Young) are revealed to exclude First Nations audiences and subsequently, First Nations content.Exploring these ideas in the documentary White Noise is a section titled “The Medium is the Message”. Two research participants explain what they witnessed while working in commercial TV, with casting director Anousha Zarkesh saying that “there is a lot of advertising, commercial, financing and investors who pull their strings” (White Noise 00:20:10). Journalist Mark Bannerman says,

The cruel reality is, Indigenous people in terms of those who have the wealth and want to spend it have been in the very lowest of percentiles and people therefore say, “Oh why do we want to tell their stories because you know who wants to see that anyway and they’ve got no money to spend.” Those kinds of conversations are had in the commercial world. (White Noise 00:19:15)

Producer Helen Bowden reflects on the current fragility of the industry, referring to the threat of the streaming platforms. She acknowledges “all television networks are under enormous pressure—their business model is breaking down quite rapidly” (White Noise 00:21:20). First Nations content is considered a risk because it is “perceived to speak to a smaller, less affluent audience—one that will not return economic benefit to the advertisers” (Nobes 119). Translating this to the Screen Idea System means that there is no “mandate” built into television ratings that encourages commercial television to commission First Nations content. The mandates commercial television managers operate under perpetuate a white bias; it is so embedded in cultural practices it is difficult to amend or change because of the postcolonialising structures that systemically preference white content for predominately white urban audiences. These commercial TV systems are biased towards white audiences and whiteness continues to be enshrined and conveyed through these commercial free-to-air advertising business models and media structures (Moreton-Robinson “Whiteness” and Whitening).

Antidiscrimination specialist Russel Robinson argues that white “male decision makers fund projects by white men, who tend to tell stories with white male leads” (7–8). Echoing this sentiment in Reel Inequality: Hollywood Actors and Racism, Nancy Wang Yuen writes:

The dominance of whites in key creative and decision-making positions (e.g., studio executives, directors, producers, writers) means more all-white casts and fewer stories featuring people of color. Even if white decision makers are not consciously racist, they can implicitly favour whites in hiring and creative decisions. (31)

In the documentary White Noise, the theme of “White Power” was discussed. Of the five First Nations practitioners interviewed, only one—Tony Briggs—had worked in the commercial realm. Briggs is an actor, writer and producer who had a recurring acting role on Neighbours between 1987 and 1988. Regarding his work as a writer and producer he says, in “terms of commercial networks those doors, from what I can tell, are closed pretty much. Why? I don’t know, I’ve never really walked through them” (White Noise 00:52:00). Susan Moylan-Coombs, former ABC executive producer and head of production at NITV, discusses the role of the ABC as a training facility which allows people to move into commercial film and television careers. Having permission to cross from noncommercial productions to commercial, however, appears to be a rare pathway open to First Nations content creators. Tony Briggs explains:

as far as I’m concerned, it’s a propaganda that THEY want out there, they want people to think that this is a white’s only country. […] They grew up watching Neighbours or Home and Away and seeing something that reflects them and so they become writers, and producers and directors and they just keep spewing the same crap out. (White Noise 00:29:00)

Showrunner and Screenwriter Kristen Dunphy comments, “I’d say the people with the power to decide what ends up on screen are the producers and the network who work to the investors and the director would have a fair amount of power about what ends up on the screen”, while RGM co-owner Jennifer Naughton says, “I think the demographic of the gatekeepers in [Australian] television is very much reflective of their audience: all white, mostly men” (White Noise 00:23:56).

The research identified an entrenched imperative, creating an uncomfortable and colourless reality whereby commercial television reflects “the faces of commercial media owners and shareholders, both in front of and behind the camera” (Nobes 123). Jack Latimore says:

The entertainment industry, television industry—it hasn’t involved a lot of Aboriginal people in senior positions. Until recently […] there hasn’t been an opportunity for Aboriginal people to be involved meaningfully. They’ve been on screen, that’s great, recently they’ve written shows or parts of shows but the fact that they’re not there suggests the structure of the way the television industry is at the moment it’s not inclusive, it’s not diverse.

This research, as focused on structural forces, reveals how First Nations creatives have been able to enter the TV drama industry through the portals of cinema and the national TV broadcasters more so than through the commercial channels. Asked if a First Nations-centric drama programme could get onto a commercial channel, executive producer Helen Bowden replied it was a possibility but “you most probably would take it to the ABC or SBS.”

Theories on knowledge and power by Michel Foucault can be mapped onto production of commercial television drama where power “is not only about the ability to influence a decision in a particular direction but also about agenda setting, determining what can be discussed and about negotiating discourses” (Lilja and Vinthagen 215). The exclusively white gatekeepers of commercial Australian TV drama have been able to set their own agendas. As of August 2021, there are no First Nations heads of drama, executive producers, or representatives on the commissioning bodies of Networks 7, 9 or 10.

The ABC has a mandate based on its charter to broadcast “programs that contribute to a sense of national identity and inform and entertain, and reflect the cultural diversity of the Australian community” (Australian). This cultural diversity mandate has been successfully implemented by ABC managers such as Head of Scripted Production, Sally Riley. As a field member and gatekeeper, Riley possessed mandated power through her management position and was able to enact that mandate by choosing to make First Nations drama productions at the ABC. Enabling this ABC mandate has unequivocally altered the tastes, trends and traditions of the domain. Over time, the screen ideas commissioned by the ABC will become exemplars that showcase the domain of First Nations drama content and the talent of those content creators.

Individual Agents: Access for First Nations Creatives

Creative individuals operate inside the system and make creative variations by having access to a domain and being willing to behave according to the rules of the domain and the opinions of the field (Csikszentmihalyi 327). From the criteria of the domain and field outlined above, it is possible to see at work the cultural, economic and social influences that have accrued over time and, in the non-commercial space, enable the commissioning of First Nations content. Paradoxically, the opposite occurred in the commercial space with these influences constraining the commissioning of First Nations content.

Colour-blind casting is a common and disputed industry term used as a counter to all-white casting. Research participants had varied responses to the practice; some believed it was progressive for characterisation (Ayres and Bowden in White Noise 00:45:05), while others felt it was an assimilationist practice (Latimore in White Noise 00:45:50). The topic was explored regarding Deborah Mailman’s role in The Secret Life of Us (2001–2006).The drama, which aired on Channel 10, revolved around the lives of a group of twenty-to-thirty-year-old inner-city Melbourne dwellers. Mailman was cast with no reference to her ethnicity and with no storylines about the character’s Aboriginality. At the time this was considered ground-breaking. Mailman’s character was seen as being progressive because she “is not seen to perform her Aboriginality through ‘issues’ driven story lines” (King 47). Mailman commented on her role saying, “It’s nice to finally have an Aboriginal person on screen that isn’t a victim of domestic violence or all those sorts of issues that affect our community” (King 47). This shift from “issue” themed narratives allows non-white characters to function as “ordinary” citizens. The casting of Mailman is discussed by Robert Connolly as evidence of colour-blind casting success (White Noise 00:43:50), while Executive Producer Tony Ayres commented:

I don’t think Deb’s character was part of a huge Indigenous world; she just fit into the world, and I think that was a political decision made by the producer. The producer, Amanda Higgs, is a very dear friend and I know she’s a great advocate for colour-blind casting and trying to represent as broader number of faces in Australia as possible on her shows.

The barriers to success for First Nations actors in the commercial drama field extend beyond the normal rigours of a casting call. Writer and showrunner Kristen Dunphy says she is often surprised that a First Nations character she has written isn’t able to be cast (White Noise 00:39:44). When questioning these casting choices, the key creatives have told her, “Oh, you know, there weren’t any… the audition tapes were no good”. As Dunphy says, “How can you argue with that? You haven’t seen it!” (White Noise 00:41:35).

Similar barriers are systemically in place for First Nations screenwriters and the question “Who has the right to write?” was debated rigorously by the research participants. All agreed to the necessity of having First Nations writers in the room when creating stories with First Nations content (Nobes 128–29). The Secret Daughter (Network 7, 2016–17) had a First Nations lead actor although storylines were initially written without First Nations creatives in the writers’ room; First Nations directors were involved, which could have somewhat mitigated this situation. Director and writer John Harvey says that Indigenous content written by white screenwriters is inauthentic and the characters appear “way undercooked.” Jack Latimore agrees saying:

It’s fairly obvious that that actor hasn’t been given enough room to work with that character and there’s not a lot of Aboriginality or Indigeneity within that character. So, I would argue, if there’s an opportunity to include more black voices in the writing then you’re going to get more texture in that character.

Kristen Dunphy says, “even when producers are looking for Indigenous writers, there is a shortage” but, as Susan Moylan-Coombs comments, “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are only a small percentage of the Australian population and an even smaller percentage of that group choose to go into the industry” (White Noise 00:37:26). The specificity of screenwriting and lack of training opportunities are also acknowledged barriers. Dunphy, who has been writing for TV for more than twenty-five years, notes that the small percentage of First Nations creatives who go into the industry often go into acting or directing rather than writing. Mentoring is a possible pathway to inclusivity but, as Dunphy asserts, this must be done in a genuine way so “the intention needs to be that … those people will go off and become fully fledged writers.”

Authenticity consistently emerged as the reason to include First Nations creatives in the writers’ rooms. Jack Latimore points out, “While it might be possible for a writer to write every character, there is the question of should they?” (White Noise 00:34:50). Filmmaker Rolf de Heer reiterated the “importance of people telling their own stories, owning their own stories and revealing all the nuances of character only lived experience can bring” (Nobes 130). As Latimore says, “Aboriginal people have unique experiences with the way they pass through contemporary Australian society and those cannot be replicated well by white writers” (White Noise 00:31:53). All the research participants agreed that these creative and power relationships need to change so that Australian commercial drama content can authentically represent First Nations stories.

Discussion

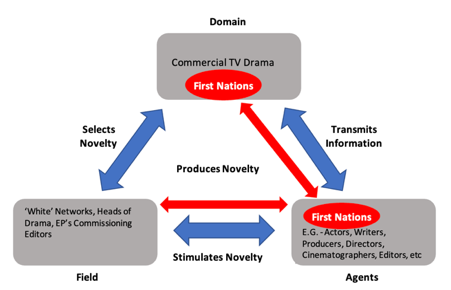

The research sought to reveal production processes in commercial TV drama production that perpetuate a “cultural terra nullius”. Mapping these barriers in a simplified way can be seen in Figure 3, “First Nations Agency in the Australian Commerical Television Drama System 2019”. Although it identifies that the domain contains First Nations content and there are active First Nations agents with access to the domain and the field, it is the field that, on balance, appears to reject screen ideas and content representing First Nations stories. The research pinpoints white characteristics, through structural postcolonialising themes that appear to be preventing First Nations access to the commercial domain of drama production. These barriers include, but are not limited to, white dominance in all positions of key creative and economic decision-making, postcolonialising issues arising within media policies, advertising agendas, ratings measurements, authentic screenwriting and casting. As the research participants attest, the field of commercial TV appears to be affected by a convergence of stagnant postcolonialising structural factors making access to this field inherently difficult for First Nations creatives (Nobes 144).

Paradoxically, from within the same system the occurrence of First Nations content occurring through non-commercial networks was evident. Future possibilities were identified, in that streaming platforms could offer additional opportunities for First Nations drama, given the policies protecting the artificial market of Australian commercial TV drama have recently been disrupted (Lotz and Sanson 9).

Figure 3: First Nations Agency in the Australian Commercial Television Drama System 2019.

Conclusion

This research is part of an ongoing conversation about the absence of First Nations presence in commercial TV drama. As illustrated by Figure 3, the key finding reveals systemic racism has been occurring in the script-to-screen production of commercial TV drama. Content produced by First Nations key creatives is not recognised by the commercial field as producing novelty acceptable to the codes and conventions of the commercial drama domain. The barriers to inclusion are implicit in media ownership, in creative control, in advertising, in content creation, in ratings measurement and in casting. The enduring theme emerging from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research participants was the lack of opportunity in the commercial space—opportunity to practise craft, to practise failure and to achieve success. Scripted drama with First Nations content is visible in the non-commercial space and protected by the Australian content regulations and the ABC and SBS charters, which include NITV. First Nations content is notable for its absence from commercial Australian television drama.

Notes

[1] First Nations content is understood as content based on an ATSI story, with Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander subjects or featuring Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander culture and heritage in any form (“Seeing”).

[2] First nations Australian dramas that have been successful include Cleverman (2016–2017), Redfern Now (2012–2015) and Mystery Road (2018–).

[3] The eight programs with more than fifty percent Indigenous main characters are “8MMM Aboriginal Radio, Black Comedy, Gods of Wheat Street, Ready for This, The Straits and two series plus the telemovie of Redfern Now” (“Seeing” 10).

References

1. Allen, Theodore W. The Invention of the White Race, Volume Two: The Origins of Racial Oppression in Anglo-America. Verso, 1994

2. Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. Australian Government, Federal Register of Legislation, Australian Broadcasting Corporation Charter,1983. 28 Nov. 2022 www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Environment_and_

Communications/ABC_Local_Content_Bill/Report/e03.3. Ayres, Tony. Filmed interview. Conducted by Karen Nobes, 16 Nov. 2016.

4. Broadcasting Services Act 1992. Australian Government, Federal Register of Legislation, 1992, compilation date 28 Nov. 2022, www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2022C00079.

5. Black Comedy. Scarlett Pictures, 2014–.

6. Blaikie, Norman. Approaches to Social Enquiry: Advancing Knowledge. Polity, 2007.

7. Bloomberg, Linda, and Marie Volpe. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation: A Road Map from Beginning to End. Sage, 2012.

8. Boaz, Judd. “Australian Television Classic Neighbours Cancelled after Failing to Find New Broadcaster.” ABC News, 3 Mar. 2022, www.abc.net.au/news/2022-03-03/neighbours-tv-show-cancelled-after-37-years/100880272.

9. Bostock, Lester. From the Dark Side: Survey of the Portrayal of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders on Commercial Television. Australian Broadcasting Authority, 1993.

10. Bowden, Helen. Filmed interview. Conducted by Karen Nobes, 16 May 2017.

11. Byrd, Jodi, and Michael Rothberg. “Between Subalternity and Indigeneity: Critical Categories for Postcolonial Studies.” Interventions, vol. 13, no. 1, 2011, pp 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369801X.2011.545574.

12. Cleverman. ABC, 2016–17.

13. Csikszentmihalyi, Mihalyi. “Implications of a Systems Perspective for the Study of Creativity.” Handbook of Creativity, edited by Robert Sternberg, Cambridge UP, 1999, pp. 313–35.

14. Delaney, Colin. “Redfern Now Set to Employ 250 jobs.” Mumbrella, 9 Nov. 2016, mumbrella.com.au/redfern-now-set-to-employ-250-jobs-72290.

15. Delgado, Richard, and Jean Stefancic. Critical White Studies: Looking Behind the Mirror. Temple UP, 1997.

16. Dunphy, Kristen. Filmed interview. Conducted by Karen Nobes, 5 Dec. 2016.

17. Dyer, Richard. White: Essays on Race and Culture. Routledge, 1997.

18. 8MMM Aboriginal Radio. Brindle Films, Princess Pictures, 2015.

19. Foucault, Michel. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. Translated by Colin Gordon, Pantheon, 1980.

20. Frankenberg, Ruth. The Social Construction of Whiteness: White Women, Race Matters. Routledge, 1993.

21. Fulton, Janet. “Mentoring and Australian Journalism.” Australian Journalism Review, vol. 36, no. 1, 2014, p. 45.

22. The Gods of Wheat Street. Every Cloud Productions, 2013–14.

23. Hall, Stuart. Representation: Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices. Vol. 2. Sage, 1997.

24. Harrison, Jane. “Indig-curious: Who Can Play Aboriginal Roles?” Platform Papers, no. 30, 2012, p. i–61.

25. Harvey, John. Filmed interview. Conducted by Karen Nobes, 16 Nov. 2016.

26. Healy, Chris. Forgetting Aborigines. UNSW Press, 2008.

27. Home and Away. Seven Studios, 1988–.

28. Jakubowicz, Andrew. “Race Media and Identity in Australia.” andrewjakubowicz.com, 2010, andrewjakubowicz.com/publications/race-media-and-identity-in-australia. Accessed 12 Nov. 2022.

29. Kerrigan, Vicki, et al. “From ‘Stuck’ to Satisfied: Aboriginal People’s Experience of Culturally Safe Care with Interpreters in a Northern Territory Hospital.” BMC Health Services Research, vol. 21, no. 548, 2021, pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06564-4.

30. King, Andrew. “Romance and Reconciliation: The Secret Life of Indigenous Sexuality on Australian Television Drama.” Journal of Australian Studies, vol. 33, no. 1, 2009, pp. 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/14443050802672528.31. Kowal, Emma. “The Politics of the Gap: Indigenous Australians, Liberal Multiculturalism, and the End of the Self-determination Era.” American Anthropology, vol. 110, no. 3, 2008, pp. 338–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12356.

32. Langton, Marcia, ‘Well, I Heard it on the Radio and I Saw it on the Television...’: An Essay for the Australian Film Commission on the Politics and Aesthetics of Filmmaking by and about Aboriginal People and Things. Australian Film Commission, 1993.

33. Latimore, Jack. Filmed interview. Conducted by Karen Nobes, 16 Nov. 2016.

34. Lilja, Mona, and Vinthagen Stellan. “Dispersed Resistance: Unpacking the Spectrum and Properties of Glaring and Everyday Resistance.” Journal of Political Power, vol. 11, no. 2, 2018, pp. 211–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2018.1478642.

35. Lotz, Amanda, and Kevin Sanson. “Foreign Ownership of Production Companies as a New Mechanism of Internationalizating Television: The Case of Australian Scripted Television.” Television and New Media, vol. 3, no. 7, 2021, pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/15274764211027222.

36. Mabo. ABC/Blackfella Films, 2012.

37. Marshall, Martin. “Sampling for Qualitative Research.” Family Practice, vol. 13, no. 6, 1996, pp. 522–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/13.6.522.

38. May, Harvey. Broadcast in Colour: Cultural Diversity and Television Programming in Four Countries. Australian Film Commission, 2002.

39. ---. “Cultural Diversity and Australian Commercial Television Drama: Policy, Industry and Recent Research Contexts.” Prometheus, vol. 19, no. 2, 2001, pp. 161–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/08109020110053532.

40. McKee, Alan. “Marking the Liminal for True Blue Aussies: The Generic Placement of Aboriginality in Australian Soap Operas.” Australian Journal of Communication, vol. 24, no. 1, 1997, pp. 42–57.

41. McQuail, Denis, and Mark Deuze. McQuail’s Medium & Mass Communication Theory. Sage, 2020.

42. Meadows, Michael. Voices in the Wilderness: Images of Aboriginal People in the Australian Media. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001.

43. Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. “I Still Call Australia Home: Indigenous Belonging and Place in a White Postcolonizing Society.” Uprootings/Regroundings: Questions of Home and Migration,edited by Sara Ahmed, et al. Berg, 2003, pp. 23–40.

44. Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. “Whiteness, Epistemology and Indigenous representation.” Whitening Race: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism, Aboriginal Studies Press, 2004, pp. 75–88.

45. ---, editor. Whitening Race: Essays in Social and Cultural Criticism, Aboriginal Studies Press, 2011.

46. Morgan, Rhiannon. Transforming Law and Institution: Indigenous Peoples, the United Nations and Human Rights. Routledge, 2011.

47. Moylan-Coombs, Susan. Filmed interview. Conducted by Karen Nobes, 15 May 2017.

48. Mystery Road. Bunya Productions, Golden Road Productions, 2018.

49. “Neighbours: Independent Review Launched over Racism Claims.” BBC Entertainment & Arts, 8 Apr. 2021, www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-56677641.

50. Neighbours. Fremantle Australia, 1985–2022.

51. Neilson. Regional TAM Television Audience Measurement. 2022, www.regionaltam.com.au/?page_id=14. Accessed 29 Nov. 2022

52. Nobes, Karen. “White Noise: A Documentary and Exegesis.” Doctoral Thesis, University of Newcastle, Australia 2020.

53. O’Dowd, Mary. “Australian Identity, History and Belonging: The Influence of White Australian Identity on Racism and the Non-acceptance of the History of Colonisation of Indigenous Australians.” International Journal of Diversity in Organisations, Communities and Nations, vol. 10, no. 6, 2011, pp. 29–44. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9532/CGP/v10i06/38941.

54. Redfern Now. Blackfella Films, 2012–15.

55. Redvall, Eva Novrup. Writing and Producing Television Drama in Denmark from The Kingdom to The Killing. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

56. Robinson, Russel. “Casting and Caste-ing: Reconciling Artistic Freedom and Antidiscrimination Norms.” California Law Review, vol. 95, no. 06-13, 2006, pp. 1–74.

57. Rourke, Alison. “Australian TV Drama Puts Spotlight on Aboriginal Life.” The Guardian,1 Nov. 2012, www.theguardian.com/world/2012/nov/01/australian-drama-aboriginal-redfern-now.

58. The Sapphires. Directed by Wayne Blair, Goalpost Pictures, 2012.

59. Saunders, Isabella. “Post-colonial Australia: Fact or Fabrication?” NEW: Emerging Scholars in Australian Indigenous Studies, vol. 2–3, no. 1, 2018, pp. 56–61. https://doi.org/10.5130/nesais.v2i1.1474.

60. The Secret Daughter. Screentime, 2016–17.

61. The Secret Life of Us. Southern Star Entertainment, 2001–2005.

62. “Seeing Ourselves: Reflections on Diversity in Australian TV Drama.” Report, Screen Australia, 2016, www.screenaustralia.gov.au/getmedia/157b05b4-255a-47b4-bd8b-9f715555fb44/tv-drama-diversity.pdf.

63. Shome, Raka. “Whiteness and the Politics of Location: Postcolonial Reflections.” Whiteness: The Communication of Social Identity, edited by Thomas K. Nakayama and Judith N. Martin, 1999, pp. 107–28.

64. Smith, Hazel, and Roger Dean. Practice-led Research and Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts. Edinburgh UP, 2009.

65. The Straits. Matchbox Pictures, 2012.

66. Te Punga Somerville, Alice. (Te Ātiawa/Taranaki). “OMG Settler Colonial Studies: Response to Lorenzo Veracini: ‘Is Settler Colonial Studies Even Useful?’” Postcolonial Studies, vol. 24, no. 2, 2021, pp. 278–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2020.1854980.

67. Ten Canoes. Directed by Rolf de Heer and Peter Djigirr, Adelaide Film Festival, 2006.

68. Thornham, Sue, and Tony Purvis. Television Drama: Theories and Identities. Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

69. The Warriors. Arena Media, 2017.

70. White Noise. Directed by Karen Nobes, National Indigenous Television Network, 2022.

71. Young, Robert. “Foucault on Race and Colonialism.” New Formations, vol. 25, no. 1, 1995, pp. 57–65.

72. Yuen, Nancy Wang. Reel Inequality: Hollywood Actors and Racism. Rutgers UP, 2016.

Suggested Citation

Nobes, Karen, and Susan Kerrigan. “White Noise: Researching the Absence of First Nations Presence in Commercial Australian Television Drama.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 24, 2022, pp. 79–96. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.24.05

Karen Nobes is a qualitative researcher and a writer, director, producer in the film and television industries of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. Karen is a White Australian. Karen’s research areas include the manifestation of systemic inequalities, racism in Australian broadcast media and critical whiteness studies. Karen’s creative practice PhD includes the feature length documentary White Noise broadcast on National Indigenous Television Australia (NITV) 2022.

Susan Kerrigan is a Professor in Film and Television at Swinburne University of Technology, Australia. She is a qualitative researcher investigating Creative Practice and Creative Industries and has published three books on these topics. Susan is on the editorial board for The Journal of Media Practice and Education and has coedited ten special issues of journals on the topics of filmmaking, practice-led research and screen production research. Susan is an Australian born, White researcher of Anglo-Celtic heritage.