Scotland’s for Me? The (Gendered) Salience of Parental Status and Geographical Location to Experiences of Working in Film and Television

Susan Berridge

[PDF]

Abstract

In recent years, international scholarship and industry reports have exposed the inherent incompatibilities between the media sector’s working cultures and caring responsibilities, focusing particularly on women who remain disproportionately responsible for childcare. The ideal media worker—characterised by geographical mobility, autonomy, adaptability and total commitment to work—is highly at odds with the material realities of parents and carers. However, despite recognition of the salience of mobility to wider (gendered) patterns of exclusion of parents, there is little scholarship that critically scrutinises the significance of geographical location on their experiences of work. This article addresses this lack, contributing to wider debates around the need to promote equity, diversity and inclusion in the film and television workforce, which, in turn, is viewed as crucial to facilitating diverse representations, voices and perspectives on-screen. Using the Scottish screen sector as a case study, the article draws on a series of one-to-one interviews with parents – both men and women – who work, or have previously worked, in the film and television industries to explore the complex ways in which gender inequalities are mediated by both geographical location and caring responsibilities.

Article

This article offers new and important insights into the powerful ways that experiences of working in the Scottish film and television industries are shaped by gender, parental status and geographical location. In recent years, international scholarship and industry reports have exposed the inherent incompatibilities between the sector’s working cultures and caring responsibilities, focusing particularly on women who remain disproportionately responsible for childcare (Wing-Fai et al.; Wreyford; Berridge; Raising Films, “Making”; Dent). Highlighting the extent of the problem, Skillset’s 2010 “Women in the Creative Media Industries” report, based on qualitative research into gendered patterns of exclusion and under-representation, found that 35% of men working in the UK media sector had dependent children living with them compared to only 23% of women (5). By comparison, in the wider UK market 75% of mothers with dependent children are in work compared to nine in ten fathers (“Families”). Indeed, the ideal media worker—characterised by geographical mobility, autonomy, adaptability and total commitment to work—is highly at odds with the material realities of parents and carers. However, despite recognition of the salience of mobility to wider (gendered) patterns of exclusion of parents, there is little scholarship that critically scrutinises the significance of geographical location on their experiences of work. This article addresses this lack, contributing to wider debates around the need to promote equity, diversity and inclusion in the film and television workforce, which in turn is viewed as crucial to facilitating diverse representations, voices and perspectives on-screen (Liddy and O’Brien; “Equalities”).

The concentration of media production in London, a city characterised by prohibitively high costs of living, a lack of affordable and flexible childcare, lengthy commuting times and intense and competitive working cultures, poses a challenge for parents—and would-be parents—working in the UK media industries. As Amy Genders observes more widely, many freelance film and television workers cited a poor quality of life and work–life balance as a key reason for leaving London and relocating elsewhere (36). The London centricity of media production has been identified as a wider concern. Writing back in 2003, Ivan Turok notes that the concentration of media production in London is “a source of growing political sensitivity, especially in the context of more general north-south regional disparities” (553–54). More recent political developments have further exposed deepening divisions between England and the rest of the UK, intensifying concerns about the wider societal impact of London-centric media production.

In this context, there has been a growing push towards developing media production in the nations and regions, evidenced by one of the UK’s main public service broadcasters, Channel 4, relocating a number of creative hubs to regional cities, including Scotland’s largest city Glasgow, and by the launch of the new BBC Scotland channel in 2019. Redistribution of media production across the UK’s nations and regions is frequently connected to a desire to improve diversity on-screen (Lee et al.). During the bidding process for the relocation of Channel 4’s hubs, the channel’s Chief Executive highlighted a commitment to reflect “the diversity of UK culture and values” on-screen, noting that “it is hard to get that diversity of thought and creativity and backgrounds that go with that if everyone works and lives in London” (qtd. in Lee et al. 7). Notably, diversity in these debates is framed in vague terms, not explicitly related to gender or parental status, but as this article will go on to explore, geographical location, gender and care are intricately bound up. Recent pushes by the Conservative Government to privatise Channel 4 and reduce the scope of the BBC threaten these ambitions, as there is little incentive for a privately owned channel to invest in local media production (Fleming).[1]

Notably, the interviews that this article draws on took place in 2018, before the launch of the dedicated BBC Scotland channel and the relocation of Channel 4’s hub to Glasgow and, as such, it is difficult to speculate on what impact these developments have had for parents working in the sector. Nevertheless, the interviews illuminate some important patterns in terms of the complex ways in which gender, parental status and geographical location overlap to shape experiences of working in Scottish film and television. The article draws on the empirical findings of twenty-six semi-structured, one-to-one interviews with parents who work, or previously worked, in the Scottish film and television sector. Fifteen of the interviews were with women and eleven were with men, with a mixture occupying freelance and staff positions. Two women had left the industry after having children, and a further woman had left temporarily while her children were young (Berridge, “Gendered Impact”). The wider project, funded by the Carnegie Trust, examined the different discourses that men and women used when talking about their experiences of negotiating childcare with work in the sector. However, throughout the interviews, geographical location emerged as a highly salient theme, meriting a deeper discussion.

The majority of interviews took place in Glasgow, where the main television broadcasters, BBC and STV, as well as several independent production companies, are located. Reflecting this Glasgow focus, twenty of the interviewees worked in television, while two further participants worked in film and four worked across both. Indeed, although the article refers to Scotland throughout—reflecting participants’ language—Scotland here is largely equated with Glasgow. Further research is urgently required into parents’ experiences of work in other parts of the country, especially as those located outside of Glasgow and Edinburgh report additional obstacles to their employment in the screen sector (“How” 45). Participants were a mixture of incomers (typically people who had moved to Scotland from other cities in England, but having worked in London for periods of time), returnees (those who had been raised in Scotland, but relocated to London early in their careers, before returning at a later stage) and long-term residents who had worked in Scotland for their entire careers. All but two of the participants were white and could be defined as middle class, and the majority were aged between 35–44 years old. There is a pressing need for further research into other barriers that workers may face, including those shaped by race, ethnicity, sexuality, ability and socioeconomic background.

Literature Review

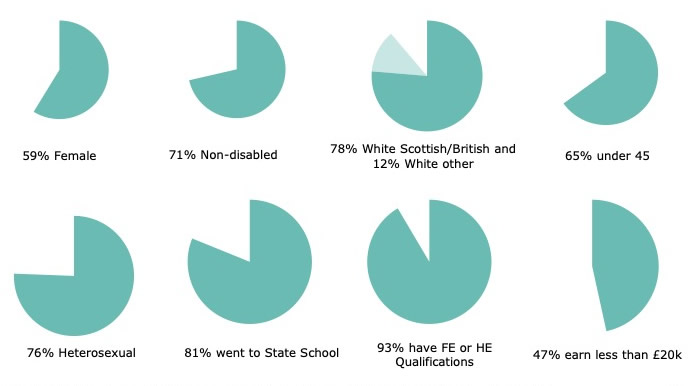

The way that gender inequalities are produced and reinforced by the film and television sector’s working cultures—characterised by long hours, precarity, erratic patterns of work, low pay, informal recruitment and eradicated boundaries between work and home lives—have been well documented by feminist scholars in recent years (Wing-Fai et al.; O’Brien; Gill). While caring responsibilities are not the only reason for women’s under-representation in the industries (Gill; Wreyford), childcare nevertheless remains a significant issue to address. A 2016 report by community interest organisation Raising Films found that 79% of respondents to their survey on parents’ and carers’ experiences of working in UK film and television viewed their caring role as having a negative impact on their position in the sector (7). Women were one-and-a-half times more likely to report on these negative impacts than men (7). Raising Films Australia carried out their own research in 2018 based on this earlier survey, with almost three-quarters of respondents—86% of them women—citing caring responsibilities as having a detrimental impact on their careers (Gregory and Verhoeven). Creative Scotland’s 2016 “Equalities, Diversity and Inclusion in the Screen Sector” report, based on a survey of up to five hundred workers specifically in the Scottish screen sector (Fig.1), similarly found that women were 75% more likely than men to cite caring responsibilities as a barrier to their career (18). This was despite more male respondents reporting having dependent children, presumably because many women had already left the sector (18).

Figure 1: Respondent Profile. “Equalities, Diversity and Inclusion in the Screen Sector: A Report on the Findings of the Screen Equality Survey by Creative Scotland.” Creative Scotland, May 2016, p. 5.

There is a small but growing body of international feminist scholarship that explores in more detail parents’ (almost exclusively mothers’) experiences of working in film and television (Wing-Fai et al.; Wreyford; Dent; Berridge, “Gendered Impact”; Liddy and O’Brien; Mayer and Columpar). As well as identifying practical barriers that childcare poses, this work has explored the complex ways that women make sense of their experiences, drawing attention to the pervasiveness of neoliberal labouring subjectivities, characterised by self-regulation and “can do” attitudes (Wing-Fai et al.; O’Brien; Berridge, “Mum”). As Rosalind Gill and Christina Scharff have identified, the ideal neoliberal subject is a highly gendered concept, with women much more than men “required to work on and transform the self, to regulate every aspect of their conduct, and to present all their actions as freely chosen” (7). This emphasis on personal choice places the onus for responsibility on individual women if they experience challenges related to gendered discrimination in the workplace, in turn rendering these experiences “unspeakable” and obscuring the structural nature of inequalities (Gill).All of this work recognises that care has long been undervalued and obfuscated in the largely freelance screen industries, which are marked by word-of-mouth recruitment and fears of reputational damage. In this context, quantitative data-gathering that seeks to uncover the numbers of parents and carers affected by inflexible working cultures that do not accommodate care adequately is vital, making it impossible for inequalities to be rationalised as simply a matter of (women’s) personal choices. Further qualitative research that renders visible and uncovers patterns across the previously hidden challenges faced by parents and carers in the sector is equally crucial in terms of highlighting the structural nature of these inequalities, thereby challenging neoliberal, individualist understandings of these issues. Indeed, any attempts to address inequalities related to care will always remain partial unless carers’ needs and experiences are fully taken into account (Gregory and Verhoeven).

Based on this research, a number of structural changes have been identified in order to address gender inequities related to care and enable parents’—especially mothers’—full participation in the sector. These solutions include the introduction of funding incentives for parents and carers, subsidies around childcare, and the inclusion of childcare costs as a viable cost in production budgets (Raising Films, “Making”; Liddy and O’Brien). Shorter working hours and more flexible forms of working have also been promoted as a crucial way to offset some of the incompatibilities between the sector’s working cultures and caring responsibilities (Liddy and O’Brien; Gregory and Verhoeven). In the UK context, trade unions such as the Broadcasting, Entertainment, Communications and Theatre Union (BECTU) and organisations such as Share My Telly Job have been essential in this respect, introducing job share initiatives as way to normalise different forms of work. In response to a recognition that freelancers face additional challenges related to a lack of workplace benefits, unpredictable working hours, irregular income and a need to network for future work, further calls have been made to address the prevalence of precarity in the sector, and to formalise recruitment (Wreyford; Wing-Fai et al.). The creation of more flexible and affordable childcare, while not specific to the film and television sector, is also seen as crucial to mothers’ retention, accompanied by a broader cultural shift that sees fathers taking on more caring responsibilities (Gregory and Verhoeven; Liddy and O’Brien).

Much of the UK creative labour scholarship on care and broader gender inequalities has focused almost exclusively on women working in London and the southeast where the majority of screen production is concentrated. However, across both industry reports and academic scholarship, questions of mobility often arise as posing specific problems for mothers (Wing-Fai et al.; Mills and Ralph). In the aforementioned Creative Scotland report, geography was the second most commonly perceived barrier after gender (32). While the open responses identified some potential positives to being situated in Scotland, such as a higher quality of life compared to London, other obstacles were also emphasised, including a need to travel, limited work opportunities and income. Respondents criticised London-based perceptions of “Scottish output” as only “of Scottish interest”, that indigenous talent is inferior to talent from elsewhere, and complained of commissioners using a “lift and shift” approach when coming to Scotland, meaning that London-based personnel are privileged over local workers. While the report did not explicitly make connections between different sections, there are striking overlaps in the sections on gender and parental responsibilities, gender and work–life balance and geographic barriers (19). There is some indication that the shift to remote, home working in response to Covid-19 may have reduced the need for mobility in the sector and opened up previously unavailable job opportunities, albeit alongside widespread financial insecurity and job losses (“How” 45; Wreyford et al. 11). At the same time, however, early research has revealed that remote labour more broadly has exacerbated existing gender inequalities, with women continuing to take on more care and domestic labour than men, especially due to school and nursery closures during lockdowns (Andrews et al.; Wreyford et al. 11).

Although many studies on the significance of location to creative production have focused on large global centres, there is an emerging body of scholarship that explores creative work in the nations and regions (Kelly and Champion; McElroy and Noonan; McElroy et al.; Lee et al.). The notion of a “talent drain” to these large centres is a key concern of this scholarship, but the appeal of regional locations in terms of quality of living has also been explored (McElroy and Noonan; Oakley and Ward; Genders). Writing in an Australian context, Susan Luckman explicitly identified caring responsibilities as a primary factor in cultural workers’ decisions to move away from large cities to regional locations, resonating with discourses emerging in the following interviews (114). Life stage, including the advent of caring responsibilities, was cited by many of my participants as a significant reason for remaining in, returning or relocating to Scotland. Distinct gendered dimensions also emerged in the discussions, pointing to the value of interviewing women and men alongside one another rather than focusing exclusively on the impact of motherhood. In the following sections, I explore in more detail parents’ accounts of both the challenges and the advantages associated with working in the Scottish film and television industries, paying careful attention to gendered differences in the way men and women talk about their experiences.

“Scottish Stories”: The (Gendered) Barriers of Geographical Location and Parental Status to Career Development, Opportunities and Retention

Across the interviews with both male and female participants, geographical location frequently emerged as having a significant impact on career opportunities available for parents working in the sector, reflecting the findings of wider media scholarship and industry reports. A need to travel and work on location, particularly due to the concentration of media production in London, were often raised as especially challenging when negotiating caring responsibilities. A man in a senior position in a staff job elaborated of the television industry specifically:

You have to go to London constantly to win business because that’s where […] all the channels are. That’s where all the agents are, that's where all the talent are, even the Scottish talent, quite often get a London agent so you have to go and meet with them. So that I think is a big problem in Scotland because you have to go to these centres and I think at different ages of your kids it will be more or less of a problem.

This man was keenly aware of the competitive advantage that child-free people, or people with older children, had in terms of their career development and opportunities, highlighting the importance of taking geographical location into account when exploring wider inequalities faced by parents working in the industries. For participants who had previously worked in London, the decision to move or return to Scotland was marked by apprehension of what it would mean for their careers. A freelance male described it as initially feeling “very much like it would actually be a step backwards” when he returned to Scotland. A female freelancer who had relocated to Scotland after working in London for several years similarly described her fear of not being “in the centre of things” when she initially moved, explaining that “it’s meant that I've maybe not been on the bigger shows and built up my CV in that way.”

Although several participants commented on the flourishing nature of the television industry in Central Scotland, both men and women described their restriction to working on local productions due to not being able, or willing, to travel as much after having children. Notably, women were much more likely to have ceased travelling altogether in order to accommodate childcare. A freelance female described her inability to travel after having children:

But it just means that, for example, the stuff that I developed, that I could have worked on, […] I just kind of knew that I was never going to be up for it because I can’t [travel or work on location] ... And it’s kind of unspoken now, I can’t do that kind of stuff. It’s self-limiting.

The use of the term “self-limiting” here underscores the way in which the challenges of the industries’ working cultures are internalised on a personal level, rather than framed as a systemic issue (Gill and Scharff). Notably, in the latter case, the woman’s partner also worked in the industry, yet she remained the primary caregiver for their children: “If there’s slack to be picked up, it’s not going to be by him.” And yet, structural patterns emerged across women’s accounts that challenge this individualised framing. Almost a third of the female interviewees had moved to part-time positions after having children, three had left the industries altogether and almost half had changed—and commonly downgraded—their roles to avoid travelling and working long hours and, in turn, accommodate childcare.

In contrast, while men also described not wanting to travel for work since having children, many still did and commonly talked about the toll that this took on family life. One man in a staff job, who had recently changed position as a result of these challenges, noted of his children that,

They were sort of getting a wee bit sad as kids that I was going to London so much […] And that sort of, guilt, I suppose, is the overriding emotion that you just feel guilty.

He had since moved to a more senior staff position with regular hours and less travel, enabling him to spend more time with his children. Another freelance male who had recently returned to Scotland commented on the need to carefully balance how much he was travelling so as not to impact his partner and children too much:

I turn lots of stuff down but really the only rationale for that has been because it’s in London and so maybe on average I’m down in London [...] a week once a month or maybe a week every two months on average. [I]t’s to do with the care and the balance of how that then feels for [my partner]. I mean the kids are affected when I go.

Conversely, women whose partners also worked in the industries were more likely to talk about the impact on them of their partner travelling, in terms of them having to assume primary caring responsibilities.Even for those who had never worked in London and had found adequate work in the Scottish sector, a further issue was identified in relation to the increasing prevalence of “lift and shift” approaches to production. A female freelance worker explained:

I always wanted to stay up here, if I always got work that I liked and was happy with. And so I've never had the pull to London. It has made it more difficult in the last ten years, and not because of my child, but [because] the industry has changed. […] A lot of […] people are getting brought up from down south.

When asked why she thought this occurred, she replied, “because they don’t think we’re as good! ((laughs)) There’s a real problem.” For her, the lack of job opportunities in Scotland was tied again to the London centricity of television production where workers from elsewhere were perceived as less skilled and less capable. In turn, this perception leads to fewer jobs for local workers, creating fewer opportunities for career and skills development which, in a sector dominated by informal recruitment and word-of-mouth recommendations, has material consequences on job prospects.

The lack of investment in the Scottish sector was identified as a key issue facing parents by another woman who freelanced in film. While participants—both male and female—commonly described the Scottish television industry as being easier to work in as parents, she argued the opposite in relation to film:

I would say it’s probably harder [to be a parent in the Scottish film industry]. Because from a freelance perspective, it’s so unknown and we don’t have a stable enough industry yet. We need this studio, we need crew to remain here, we need some of the touristy places, our shoot locations to be less busy, in an ideal world! […] So I feel that it’s harder because there’s not, in my mind, a strong enough film and TV industry to make it regular enough.

These accounts speak to the importance of building greater infrastructure and investing in media production across the nations and regions, in turn creating more local job opportunities and facilitating training and skills development, potentially mitigating against a need for mobility in workers. The recent push by the Conservative government to diminish the scope of and privatise public service broadcasting in the UK greatly threatens this development, as a privately owned channel arguably has little reason to invest in media production outside of London (Fleming).

Despite identifying challenges related to the London-centric nature of the UK screen sector, participants largely accepted that working in Scotland would impact their career opportunities. One man commented, “I don’t know how you address that. I don’t think there’s a way that you can change that.” Writing on the Australian screen sector, Gregory and Verhoeven attribute the lack of discussions about “workplace flexibility or broader industrial innovation” to the prevalence of freelance and opaque working cultures, where workers lack rights and fear discrimination related to their carer status (25). Their findings resonate with the findings presented here, where both men and women recognise the challenges of negotiating care with media work but largely expect to manage these difficulties on a personal level. Women disproportionately bear, and often internalise, the brunt of this care labour with material impacts on their career development, opportunities and retention.

Scotland’s for Me: The Advantages of Working in Scotland in Terms of Negotiating Caring Responsibilities

Despite the challenges identified by both men and women in relation to navigating childcare and work in the Scottish sector, working in Central Scotland was simultaneously seen to offer certain benefits in terms of being conducive to a relatively good work–life balance, resonating with broader scholarship and industry reports that associate a higher quality of life with media work in the nations and regions (Genders). While scholars have critiqued the under-theorisation of the term “work–life balance” as being exclusively used in relation to the negotiation between work and family life (Eikhof and Warhurst), notably both male and female participants defined the term more broadly, using it encompass social lives with friends, relationships with partners, hobbies and exercise. A freelance woman explained:

I would say people are just a bit more respecting of work–life balance [in Scotland]. […] people left at six o’clock to go away and go to an exercise class or actually, have a bit of a life. That was my experience of it, definitely. [T]he shoots were really hard, they were long hours […] but you didn’t need to do that when the crunch points weren’t there. People were happy for you to leave and have time out of work as well.

Many participants made an explicit connection between the small size of the sector, which allows for particularly close networks to develop, and a greater understanding of the realities of balancing caring responsibilities with work. Several freelance participants spoke of working for relatively long periods of time within the same independent production companies and with the same people. As one male freelancer explained,

Obviously, when you’re 18 you dream of “oh go down to London” but actually it’s really good up here, it’s a good industry and people are actually quite understanding when you are a parent. You can kind of work around that, most of the time.

A male in a staff job similarly drew on London as a comparison, noting that, “I think Scotland’s a bit friendlier, generally, because everyone knows each other a bit better.” Referring specifically to the Scottish film and television industries, Turok explains the advantage of geographical closeness in terms of mitigating against the inherent risks of creative production, noting that, “Proximity fosters collaboration, including interpersonal relationships, trust and a sense of common interest” (552).

However, this intimacy related to the small size of the Scottish sector was experienced differently by male and female participants. Several male participants identified the sector’s close, professional relationships as offering certain advantages around care. A freelance male described regularly showing off photographs of his young child to colleagues, while another freelance man noted that his family life was a key part of his relationship with many directors. In contrast, while none of the female participants felt that caring responsibilities were explicitly silenced by the industries, they often nevertheless described feeling more cautious about to whom they disclosed details of parental responsibilities. Many women were keenly aware of perceptions of mothers as at odds with the ideal creative worker and spoke of going to considerable lengths to disprove these views, a tendency that was heightened in relation to freelancers and single mothers. The contrasting perceptions of male and female participants reflect wider feminist media scholarship on the different gendered values ascribed to men and women in the workplace. While women’s status as “inevitable mothers” works against them in the industries (Wreyford 112), fatherhood has less material impact on men’s careers, and may even work in their favour to increase their value (Dent).

Despite this awareness of negative perceptions around motherhood in the sector, the Scottish sector was still described by women as more understanding of the realities of care than London, which was perceived to have a greater culture of “presenteeism”, longer hours and heightened job competition. London was frequently invoked as the “bad other” to Scotland, offering an alternative to discourses around a “talent drain” of skilled workers from the nations and regions. A woman who had worked in London before returning to Scotland to start a family commented, “Oh, it’s no life! I hated it, I absolutely hated it!” A female in a staff job who had previously worked in London similarly explained:

I felt that in London it was far, far less... what’s the word… not “nurturing” but understanding of just life, really. At that point it wasn’t even that I had children, it was just expected… and I hated it. I ended up just making myself really ill and thinking “right, I need to go back to […] Scotland”, not that I’d ever worked here but I had friends here and I do think it is a much nicer environment here.

Other participants who had previously worked in London before coming or returning to Scotland often recounted their experiences with a degree of pride and excitement, naming well-known programmes they had worked on or directors with whom they had worked. However, there was a simultaneous recognition of the London sector’s punishing working cultures and the impact that these had on wellbeing and quality of life. A woman in a staff position commented:

I worked on […] big Saturday-night shows [in London]. But I was really, ((half sighs)) I never got paid enough to live anywhere nice. I was working absolutely crazy hours, it was a six-day week or a seven-day week...

Working in London was often associated with youth and a life stage free of other responsibilities, resonating with wider arguments about the television industry as an especially young sector (Kelly and Champion). However, the advent of a time in life when other responsibilities besides work became important was identified by several participants, both male and female, as a catalyst for critical reflection on the sector’s intense working cultures. A freelance male who had formerly worked in London before moving to Scotland explained:

When you're in your early twenties it’s like, “Great, I've got a job in TV’ and I was… messing around on film sets. It was great! It’s better than working in an office… But there becomes a point where that enthusiasm and that willingness to do that, you’ve just got to get yourself in check and think, “Actually, this is my career, this is business and the contract that I have with my employer, is a two-way thing.”

He went on to explicitly critique the intensity of the London sector’s working cultures, which contributed to his decision to leave. A freelance woman, who had reduced her hours after having children, similarly commented on the relationship between life stage and a desire for a richer quality of life beyond work:

There’s a tipping point where your house is nicer than the hotel room, the life at home is more interesting, or not more interesting but there’s more of a pull to your life at home, whatever that is—a partner, a dog, some kids, something—friends, whatever. The pull of your life at home tips the balance.

For many participants, this “tipping point” arrived before they had children, and was a key factor in their decision to stop travelling or to leave London and move or return to Scotland, resonating with wider scholarship around creative workers’ mobility (Luckman).

This idea of a “tipping point” could be viewed as a driver in implementing structural change in the sector, accompanied as it is with critical reflection of the unsustainability of the (London) sector’s working cultures. And yet, while workers were aware of the incompatibilities between London-based media work and childcare—or any other commitment beyond work—this awareness did not necessarily translate into explicit positions of resistance. Instead, they largely managed these contradictions themselves by relocating or returning to Scotland and, in several women’s cases, reducing their hours, changing positions or leaving the industries altogether. This response reflects the findings of Susan Liddy and Anne O’Brien who observed that mothers working in Irish media internalised their responsibility for care, and directed “their energy towards coping strategies” rather than proposing possibilities for collective action (205).

A notable gendered dimension emerged across these discussions. While men often spoke of being motivated to move or return to Scotland due to a broader desire for a richer quality of life, women recalled making their decisions based explicitly on the lack of mothers working in the London sector. A woman in a part-time staff position recounted being keenly aware of this invisibility: “I really loved the jobs that I did down in London but it was really hard work and I could never see how I could manage to have a family as well.” London-based living was repeatedly deemed by female participants as incompatible with caring responsibilities, and very few had started their families while living and working in the city. The lack of affordable housing in London and the substantial time and expense spent commuting was repeatedly raised. In her research on freelance labour in Bristol’s film and television industries, Genders similarly found that “reduced quality of life, high cost of living and poor work/life balance” and “the highly competitive and ‘cut throat’ nature of working in London” were often cited as reasons for relocating elsewhere (36). A freelance woman explicitly described the differences between Scotland and London:

TV culture is different in Scotland from London. […] People are less likely to have settled down and have families [in London], because of all the travelling and because, I don’t know, maybe you’ve got bigger shows up there and it’s this really big club and you’re in the middle of London and it’s that fast city. And some people would say that really doesn’t always work for families.

Finding suitable nursery provision in London was also deemed difficult, due to the incompatibility between lengthy commutes, the sector’s long hours and the rigidity of nursery hours. A proximity to family networks that can help with childcare was thus a key consideration for a third of participants in terms of their geographical location, reflecting the findings of industry reports (Raising Films, “Making”). There was a perception across the interviews that being located in Scotland would make it easier to facilitate these kinds of networks than being London-based. A man in a staff job explained, “family network is important. And up here it’s closer, so if you've got more lenient line managers and family close at hand, you can kind of make it work. I don’t think that would exist in London as easily.” The way in which the challenges of childcare are handled on a personal level rather than collectively and reliant on understanding managers, points to the wider individualisation of risk in the industries, where workers need to “seek personal solutions to systemic contradictions” of the increasingly casualised workplace (Ulrich Beck and Elisabeth Beck-Gernsheim qtd. in Lee 206).

A woman who worked in the film industry in a staff position explained the significance of this family support in terms of her career development:

I mean I couldn’t do anything that I’ve done without that [family] support. Because I’ve had opportunities to move [abroad] but there’s just no way that you could do this job without the family structure around us.

Another freelance woman, who was a single mother, had returned to Scotland in order to be closer to her parents both to access childcare, but also to provide care. Care provided by wider family networks, most commonly grandparents, was not one-way. Four of the participants, both male and female, had actively made decisions to remain or move back to Scotland due to their own caring responsibilities for ageing parents. Adaptability and mobility may be prized characteristics of the ideal creative worker, but the interviews reveal the incompatibilities between the material realities of parents’ and carers’ lives and the industries’ working cultures. In recent years, there have been important initiatives designed to address the lack of flexible and affordable childcare in the sector, including The WonderWorks that provides flexible childcare to people working in the Warner Bros. Studios Leavesden, and Nipperabout, that offers mobile childcare to those working on location (“How”). These solutions are vital and need to be rolled out more widely across the UK, yet as the interviews reveal, caring responsibilities also extend beyond early-years childcare, necessitating a much wider state response to address significant gaps in care provision.

Conclusion

This article has drawn on the accounts of parents working in the Scottish film and television industries to identify recurring ways in which geographical location and parental status intersect to shape their experiences of work. The advent of a life stage where other factors—including planning for having children—take priority over work acts as a catalyst for critical reflection on the unsustainability of working cultures in the media sector. Resonating with wider scholarship on creative labour in nations and regions, both male and female participants associated being located in Central Scotland with a higher quality of life and greater understanding of the realities of combining work and childcare, which was frequently attributed to the sector’s small size and close working networks.

And yet, the understanding nature of the Scottish sector was frequently attributed to individual line managers in a way that is fragile and precarious. Further, women and men experience this understanding in distinctly different ways, with women expressing much more caution about to whom they disclose challenges. The difficulties of managing childcare with work in the film and television industries were still typically viewed by parents as their responsibility, illustrated by the fact that a key way that these challenges were addressed was by relocating, returning to or staying in Scotland, often in order to be close to family networks that could help fill in childcare gaps when working hours are long and unpredictable. Women disproportionately bear the brunt of this care labour, commonly reducing their hours, downgrading their position or, sometimes, leaving the industries altogether to accommodate caring responsibilities even when they reported sharing this childcare equally with a partner.

The expectation and acceptance that parents and carers will manage the incompatibilities of the workplace on a personal level—including moving to the nations and regions to access family support and secure a higher quality of life—largely lets the industries off the hook. In turn, this allows the industries to continue to focus on those entrants who can most easily embody the ideal neoliberal worker, typically characterised as young, able-bodied, geographically mobile, free from commitments and able to withstand working for low—sometimes no—pay. This has powerful implications for diversity both on- and off-screen, essentially excluding anyone who is unable to offer this level of overwork. There is also urgent work to be done to address the persistence of racial inequalities in the sector.

Writing specifically on the Scottish screen industries, Lisa Kelly and Katherine Champion argue that, “in order to maintain and expand Scotland’s talent pool, issues of diversity, skills development and retention must continually be addressed” (168). Not all geographical areas can have the same scale of industry, but redistributing media production across the nations and regions is an important way that some of the challenges associated with combining work and childcare in the Scottish sector can be addressed, potentially mitigating against such a common need to travel and opening up further opportunities to local workers. At time of writing, this expansion of national and regional media production is greatly under threat by the Conservative Government’s plans to diminish the scope of public service broadcasting, as channels like the BBC are crucial in providing relatively stable forms of employment in a precarious sector, growing independent production outside of London and the southeast, and creating skills and development training (Fleming).

The creation of more local work alone will not help solve gender inequalities related to care. Investment in local media production needs to be accompanied by radical changes to working cultures and the provision of more accessible and flexible care, as well as wider cultural shifts to challenge the deep and essentialised connection between women and childcare. Although the interviews took place prior to Covid-19, the pandemic has arguably challenged the rigidity of traditional working models, highlighting the viability of remote and flexible working and challenging the idea of London as “the centre of the universe” (“How” 45). It will be interesting to see if these alternative labour practices continue to be upheld in the future, and whether this will have a material impact on existing inequalities in the workforce.

Funding Disclosure

This work was supported by the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland [70680].

Note

[1] At the time that this article was written, the then Culture Secretary Nadine Dorries had announced plans to privatise Channel 4 and freeze the licence fee that funds the BBC. Since then, there have been two new Prime Ministers and a new Culture Secretary. With these changes, the plans are now under review, and the implications of what this will mean for media production in the nations and regions remain unknown.

References

1. Andrews, Alison, et al. “How Are Mothers and Fathers Balancing Work and Family Under Lockdown?” IFS Briefing Note BN290. Institute of Fiscal Studies, 2020, ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/output_url_files/BN290-Mothers-and-fathers-balancing-work-and-life-under-lockdown.pdf. Accessed 7 July 2020.

2. Berridge, Susan. “Mum’s the Word: Public Testimonials and Gendered Experiences of Negotiating Caring Responsibilities with Work in the Film and Television Industries.” European Journal of Cultural Studies, vol. 22, no. 5–6, 2019, pp. 646–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549419839876.

3. ---. “The Gendered Impact of Caring Responsibilities on Parents: Experiences of Working in the Film and Television Industries.” Feminist Media Studies, vol. 22, no. 1, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1778763.

4. Dent, Tamsyn. “Devalued Women, Valued Men: Motherhood, Class and Neoliberal Feminism in the Creative Media Industries.” Media, Culture, Society, vol. 42, no. 4, 2020, pp. 537–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719876537.

5. Eikhof, Doris, and Chris Warhurst. “The Promised Land? Why Social Inequalities Are Systemic in the Creative Industries.” Employee Relations, vol. 35, no. 5, 2013, pp. 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-08-2012-0061.

6. “Equalities, Diversity and Inclusion in the Screen Sector: A Report on the Findings of the Screen Equality Survey by Creative Scotland.” Creative Scotland, May 2016, www.creativescotland.com/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/35020/ScreenEqualitiesSurveyMay2016.pdf. Accessed 25 Feb. 2022.

7. “Families and the Labour Market: UK 2019.”Office for National Statistics, UK, 2019, www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/ familiesandthelabourmarketengland/2019. Accessed 25 Jan. 2022.

8. Fleming, Paul W. “How to Save the BBC.” Tribune Magazine,17 Jan. 2022, www.tribunemag.co.uk/2022/01/bbc-licence-fee-media-reform-journalism-equity-trade-unions. Accessed 25 Jan. 2022.

9. Genders, Amy. “An Invisible Army: The Role of Freelance Labour in Bristol’s Film and Television Industries.” Project Report, University of the West of England, UK, 2019. uwe-repository.worktribe.com/OutputFile/849508. Accessed 13 Nov. 2022.

10. Gill, Rosalind. “Unspeakable Inequalities: Post Feminism, Entrepreneurial Subjectivity and the Repudiation of Sexism Among Cultural Workers.” Social Politics, vol. 21, no. 4, 2014, pp. 509–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxu016.

11. Gill, Rosalind, and Christina Scharff. “Introduction.” New Femininities: Postfeminism, Neoliberalism and Subjectivity, edited by Rosalind Gill and Christina Scharff,Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, pp. 1–17.

12. Gregory, Sheree K., and Deb Verhoeven. “Inequality, Invisibility and Inflexibility: Mothers and Carers Navigating Careers in the Australian Screen Industries.” Media Work, Mothers and Motherhood: Negotiating the International Audiovisual Industry, edited by Susan Liddy and Anne O’Brien, Routledge, pp. 13–29.

13. “How We Work Now: Learning from the Impact of COVID-19 to Build an Industry that Works for Parents and Carers.” Report, Raising Films, 2021, www.raisingfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Raising-Films-How-We-Work-Now-2021-Full-Report.pdf. Accessed 26 Feb. 2022.

14. Kelly, Lisa, and Katherine Champion. “Shaping screen talent: Conceptualising and Developing the Film and Television Workforce in Scotland.” Cultural Trends, vol. 24, no. 2, 2015, pp. 165–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2015.1031482.

15. Lee, David. Independent Television Production in the UK. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

16. Lee, David, et al. “Relocation, Relocation, Relocation: Examining the Narratives Surrounding the Channel 4 Move to Regional Production Hubs.” Cultural Trends,vol. 31, no. 3, 2021, pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2021.1966296.

17. Liddy, Susan, and Anne O’Brien, editors. Media Work, Mothers and Motherhood: Negotiating the International Audiovisual Industry.Routledge, 2021.

18. Luckman, Susan. Locating Cultural Work: The politics and Poetics of Rural, Regional and Remote Creativity. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

19. “Making It Possible: Voices of Parents and Carers in the UK Film and TV Industry.” Report, Raising Films, 2016, https://www.raisingfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Making-It-Possible-Full-Report-Results.pdf. Accessed 24 Feb. 2022.

20. Mayer, So, and Corinn Columpar, editors. Mothers of Invention: Film, Media, and Caregiving Labor.Wayne UP, 2022.

21. McElroy, Ruth, and Caitriona Noonan. “Television Drama Production in Small Nations: Mobilities in a Changing Ecology.” Journal of Popular Television, vol. 4, no. 1, 2016, pp. 109–27. https://doi.org/10.1386/jptv.4.1.109_1.

22. McElroy, Ruth, et al. “Small Is Beautiful? The Salience of Scale and Power to Three European Cultures of TV Production.” Critical Studies in Television, vol. 13, no. 2, 2018, pp. 169–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749602018763566.

23. Mills, Brett, and Sarah Ralph. “‘I Think Women are Possibly Judged More Harshly with Comedy’: Women and British Television Comedy Production.” Critical Studies in Television, vol. 20, no. 2, 2015, pp. 102–17. https://doi.org/10.7227/CST.10.2.8.

24. Oakley, Kate, and Jonathan Ward. “The Art of the Good Life: Culture and Sustainable Prosperity.” Cultural Trends, vol. 27, no. 1, 2016, pp. 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/09548963.2018.1415408.

25. O’Brien, Anne. Women, Inequality and Media Work. Routledge, 2019.

26. Skillset. “Women in the Creative Media Industries.” Report, Sept. 2010. www.raisingfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Raising-Films-How-We-Work-Now-2021-Full-Report.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan. 2022.

27. Turok, Ivan. “Cities, Clusters and Creative Industries: The Case of Film and Television in Scotland.” European Planning Studies, vol. 11, no. 5, 2003, pp. 549–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310303652.

28. Wing-Fai, Leung, et al. “Getting In, Getting On, Getting Out? Women as Career Scramblers in the UK Film and Television Industries.” The Sociological Review, vol. 63, no. S1, 2015, pp. 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12240.

29. Wreyford, Natalie. Gender Inequality in Screenwriting Work. Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

30. Wreyford, Natalie, et al. “Locked Down and Locked Out: The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mothers Working in the UK Television Industry.” Report, 2021. Nottingham UP, http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/research/groups/isir/documents/locked-down-locked-up-full-report-august-2021.pdf. Accessed 22 Nov. 2022

Suggested Citation

Berridge, Susan. “Scotland’s for Me? The (Gendered) Salience of Parental Status and Geographical Location to Experiences of Working in Film and Television.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 24, 2022, pp. 64–78. DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.24.04

Susan Berridge is Senior Lecturer in Film and Media at the University of Stirling. Her research is focused on gender inequalities on/off screen in the film and TV industries. She is currently working on two collaborative funded projects: one on the role of intimacy coordinators in contemporary UK television, and another on the networks of care mobilised by creative hubs in response to Covid-19. Previous research has explored the gendered impact of caring responsibilities on work in the screen sector, and representations of gender, sexuality, sexual violence and age in popular culture more widely.