Hands in the Machine: Maya Deren and Marie Menken’s Manual Gestures

Saige Walton

Abstract

In this article, I examine how Maya Deren and Marie Menken’s mid-1940s filmmaking enacts a gestural aesthetic. Drawing on Vilém Flusser’s thinking on gesture (his discussion of “moving tools” and the thoughtfulness of hands), I draw attention to the importance of hands in Deren and Menken’s work. In Visual Variations on Noguchi (1945), Menken employs a handheld Bolex camera to explore the different material properties of art objects. Through her sweeping camerawork, film editing and sound, she transforms Noguchi’s art into new, cinematically stuttering, borderline abstract compositions. In At Land (1944), Deren’s unnamed protagonist (played by Deren herself) is filmed reaching, touching, clasping and grasping her way through a highly mutable world. In Deren’s re-working of the mythic quest narrative, hands function as a gestural, thoughtful means of adaptation. Hands also provide Deren with a manual means of manipulating “film form”, of manually piecing together different surfaces, shots and scenes. In Visual Variations on Noguchi and in At Land, both artist-filmmakers use their “moving tools” to transform human gesture. Through their foregrounding of the hands (onscreen and offscreen), Deren and Menken enact a desubjectified, gestural cinema.

Article

“Each pair of hands has its special ways and means of asserting itself in the world.” (Flusser 24)

In this article, I bring the work of two female experimental filmmakers together to consider their complementary approaches to film during the mid-1940s: Maya Deren and Marie Menken. Although they were both central to the development of American avant-garde filmmaking (Deren, especially), the parallels between these two figures have yet to be fully explored. Drawing on Vilém Flusser’s phenomenologically inflected thinking on gesture, I argue that Deren’s and Menken’s cinema enacts a hand-based, gestural aesthetic. Through the gestures of their “moving tools”, Deren and Menken reach out towards and technically manipulate the “world of objects” (Flusser 166, 34).

In what follows, I first contrast Flusser’s understanding of gesture with the artistic gestures that were associated with abstract expressionism—a postwar movement in American painting that coincided with Deren’s and Menken’s cinema. With reference to Harold Rosenberg’s 1952 article “The American Action Painters”, I detail how the gestural rhetoric surrounding this art movement fed into American avant-garde film circles, shaping the reception of Menken’s “somatic camera” (Sitney 23).[1] Focusing on Menken’s first film, Visual Variations on Noguchi (1945), including her later addition of a film score, I explore Menken’s handheld approach to film, arguing that it is more invested in the manipulation of objects than subjective markings. In Visual Variations on Noguchi, the first of her dedicated films on art, Menken transforms Noguchi’s art into new sweeping, stuttering audiovisual combinations.[2]

Drawing on Deren’s An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film (hereafter: An Anagram) (1946) and other selected writings by Deren, I argue that Deren’s complex, layered understanding of film form is premised on a similar refusal of artistic individualism. Focusing on Deren’s At Land (1944), a film that Menken helped to animate, I explore the significance of the hands for Deren. In At Land, hands function as a thoughtful, gestural means of adaption, as they do in Flusser’s thinking. Hands also function as a means for Deren to film, edit and piece together her imaginative traversals of the body, space, time and landscape.

Running counter to the masculine cult of the gesture in postwar American art and experimental film circles, Deren and Menken can be associated with a different gestural aesthetic.[3] While playing on the “concrete movement” of hands in their work—Menken through her handheld camera and Deren through her reliance on the gesturing body—both artist-filmmakers refuse to use cinema as a medium of interiority or self-portraiture (Flusser 32). In Visual Variations on Noguchi and in At Land, Menken and Deren employ the hands to enact a desubjectified, gestural cinema.

Sweeping Gestures, Distorted Sounds: Visual Variations on Noguchi

In Gestures, media theorist Vilém Flusser develops a general theory of gestures that is inextricably embodied and intimately bound up with movement. As it derives from the Latin word gestae (meaning “acts, deeds”), Flusser frames gesture as an expression of our active being-in-the-world (166). Distinguishing gestures from involuntary physical reflexes, he associates gesture with “expressions of freedom” (expressions of “inwardness” that are transferred outwards and made visible to others) (163).[4] In Gestures, he identifies two different types of gestures: those “in which a human body moves” and those “in which something else connected to a human body moves” (164). Whereas the first type of gesture corresponds with the intentional movement, action and thought of individual bodies/subjects, the second pertains to the movement of tools (a pen, a paintbrush, a camera and so on). Citing the motion of a pen, he asserts: “it is exactly the difference between the gesture of moving fingers and the gesture of the moving pen that is of interest in determining the essential […] in gestures” (165).

As Martine Beugnet observes, Flusser’s efforts to consider the “effects of technology” upon human gesture is essential to his thinking (5). Of particular interest to me with regards to both Deren and Menken’s filmmaking is Flusser’s discussion of a mediated gestural freedom.[5] Rather than delimiting tools to a prosthetic extension of the human or seeing tool-based movement as equivalent to human motion, he defines tools “in such a way as to encompass everything that moves in a gesture […] everything that is an expression of freedom” (165; emphasis added).

Menken achieved a mediated freedom of movement in her cinema through her signature sweeping, handheld use of the Bolex camera. Oftentimes, this involved the artist-filmmaker moving “to and from the photographed field or back and forth before it” (Tyler 158). Originally trained as a painter, Menken was known for making abstract paintings and collages that combined natural and manufactured materials (sand, stone chips, string, sequins, phosphorescent paint and crushed glass, among other substances).[6] In a 1962 interview given with P. Adams Sitney, she reflects on her shift into filmmaking as a delight in “the twitters of the machine” (qtd. in Sitney 24). The shift between art and film afforded her greater freedom to explore the formal possibilities of materiality and movement. In “painting I never liked the staid static”, she recounts, “[I] always looked for what would change with source of light and stance, using glitters, glass beads, luminous paints, so the camera was a natural extension for me […]” (qtd. in Sitney 24; emphasis added).

Thanks to her background as a painter and her freeform use of the Bolex, Menken’s filmmaking style has often been compared with the painterly style of the abstract expressionists.[7] For Scott MacDonald, Menken was the first to make “gestural camerawork a hallmark of style”, achieving a “gestural freedom” in film that was commensurate with postwar painting (“Women’s” 378; “Filmmaker” 3). Similarly, Sitney likens Menken’s filmmaking to “an action painter’s […] purview” (33). For the American experimental filmmaker, Stan Brakhage, one of Menken’s most vocal stylistic proponents, Menken’s intimate use of the Bolex expresses a “‘oneness’ between body and camera” (qtd. in Hart 42).[8] For Brakhage, “oneness” with the camera parallels the “intensity” of the gesture in abstract expressionism (qtd. in Scott MacDonald, “Filmmaker” 5).

Perhaps no movement in American painting has been as closely associated with the individual markings and movements of the artist than abstract expressionism, especially the New York set of painters dubbed the “action painters” by the art critic Harold Rosenberg (artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline). Whether “making an image by means of an airborne gesture”, as Rosalind Krauss once described Pollock’s process, or by employing other painterly techniques on a large scale (dripping, smearing or splattering), the liquid markings of these artists were equated with a heightened, gestural style (302).

Glossing action painting as the moment in which the canvas became “an arena in which to act”, Rosenberg’s descriptions of the male action painter at work provide a typical case in point. As he writes: “The [action] painter no longer approached his easel with an image in mind; he went up to it with material in his hand to do something to that other piece of material in front of him. The image would be the result of this encounter” (190).

For Rosenberg, the artist’s end results (the final image) seem to occur magically and spontaneously the moment they come into contact with their materials.[9] Whereas Flusser distinguishes between human and tool-based gestures, Rosenberg conflates the artist’s body with their tools. By “gesturing with materials”, he writes, the action painter does away with anything “that would get in the way of the act of painting” (191). He frames action painting as an intense, physical performance. As an imprint of the artist’s presence, the canvas borders on the cinematic. It functions as a veritable, time-based recording of the “actual minutes taken up with spotting the canvas” (192).

As Adam Hart documents, the burgeoning of American avant-garde filmmaking was greatly influenced by this kind of gestural rhetoric. By the mid-1960s, experimental filmmakers such as Brakhage and Jonas Mekas were readily equating the embodied eye/“I” of the filmmaker with the handheld camera and with other subjective filmmaking techniques (a legacy that continues with Sitney’s “somatic camera”). As a point of contrast, one that is more in line with Menken’s practice, it is useful to consider Annette Michelson’s articulation of an alternate point of view during this period. In her 1966 article “Film and the Radical Aspiration” (first delivered as an address to the New York Film Festival), Michelson openly criticises the incursion of “abstract expressionist orthodoxy” into film theory, singling out critics such as Rosenberg for “defaulting to the action painter’s active authority” and for failing to recognise mediation. The “idea of the camera as an extension of the body or its nervous system seems […] highly questionable”, she asserts, also taking issue with Brakhage’s body–camera conjunction. For Michelson, as for Menken, the indexical conflation of the embodied eye/“I” of the filmmaker ultimately “limits and violates the camera’s function”, reducing filmmaking to “a crude automatism” (“Film”).

To my mind it is precisely because of Menken’s longstanding association with “gestural painting” (Scott MacDonald, “Women’s” 379), the “somatic camera” (Sitney 23) and “dance-like movement” (Sheehan 187) that the radically non-human, technical gestures of her cinema tend to be elided. In her article “Swing and Sway: Marie Menken’s Filmic Events”, Melissa Ragona offers a valuable counterpoint to such readings. Not only did Menken refuse the “uniqueness of the painterly mark in film”, but she also maintains her filmmaking never sought to conflate the filmmaker’s eye with the “camera eye” (21, 29). In making the transition between art and film, Menken’s approach was deeply concept-based (depending on the particular project at hand). While attending to different surface materials, light and the liveliness of objects, all features of her art, film opened up new ways for Menken to manually handle, rearrange, pattern and reorder the world.

At the core of Visual Variations on Noguchi are Menken’s sweeping gestures, achieved through the handheld Bolex. Invited to visit the studio of the Japanese American artist Isamu Noguchi, Menken recalls how she “had the advantage of looking around Isamu’s studio with a clear, unobstructed eye” (qtd. in Sitney 24).[10] Her shot compositions do not express a general clarity of vision, however. Shot in black and white, the film swerves between close-up and medium shots, interspersed with footage of light and shadow patterns inside the studio space. If the “rapid pace of the film prohibits contemplation of the sculpture[s]”, as Sitney suggests, the film’s many shifts in perspective are held together by one gestural constant—Menken’s sweeping camera (27).

Not often discussed in relation to Menken’s first film is the fact that it was revised during the 1950s to incorporate a film score and released through the Gryphon Group (the experimental collective cofounded by Menken and her husband, the American poet-filmmaker Willard Maas). For what she regarded as the film’s definitive version, Menken commissioned Polish American composer Lucia Dlugoszewski in 1953 to create a sonically jarring musical score. Titled the poetry of natural sound, the film’s musical score is shot through with the unusual, echoing sounds of Dlugoszewski’s timbre piano, distorted voices and the cryptic recitation of words and names from Gertrude Stein’s 1951 play Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights.[11] In addition, Dlugoszewski integrates a number of “everyday sounds” into the score (torn paper, the lighting of matches, rattling glass or the dropping of books onto the floor), heightening the score’s eclecticism and the sense of an audiovisual disconnect between Menken’s frenzied images and the soundtrack (Lewis 13–4).

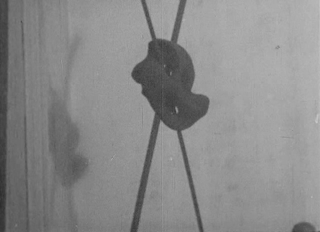

Over the film’s opening title card, footsteps and whispered words (“sidewalk”, “lithium”) begin, followed by the scratching of a comb and other clanging sounds. For her cinematic ode to Noguchi, Menken opens with the hazy shot of a white, slightly rounded sculpture, suspended in the air. Next, the camera hastens down a twisted, wooden sculpture. In extreme close-up, the fine grain markings of the sculpture are brought into sharp relief. As with Menken’s other highly textured shots, the camera’s proximate vision “searches, peers into and explores the properties” of Noguchi’s art, revelling in their texture, shape and materiality (Shana MacDonald) (Fig. 1). A cut brings about a quite literal swerve in the film. Menken’s camera begins to sweep horizontally, taking in one of Noguchi’s interlocking pieces located in the corner of the studio and its patterned shadows on the walls (Fig. 2). As the sound of bells erupts, the film switches intentional focus again. This time, the camera lingers on another set of shadows on the studio’s walls before veering onto the sharpened, geometric edges of a sculpture, accompanied by the sounds of breath.

Figure 1 (above): Textured close-ups in Visual Variations on Noguchi (Marie Menken).

Figure 2 (below): An interlocking piece in Visual Variations on Noguchi. Gryphon Productions, 1945. Avant-Garde 2: Experimental Cinema 1928–1954, Kino International, DVD, 2007. Screenshots.

After sweeping left to right along the surface of a sculpture, Menken’s camera then begins to hasten downward. Sounds of laughter and water bubbling filter through the score, creating a curious, submerged effect. Like other anempathetic sounds that feature in the film (clapping hands, breath, whispered words), the score’s aquatic sounds bear no obvious relationship to Noguchi’s art. Rather, Menken’s addition of a layered, noisy soundtrack corresponds with her broader efforts to transform sculpture and to disorient the viewer’s senses through the cinema.

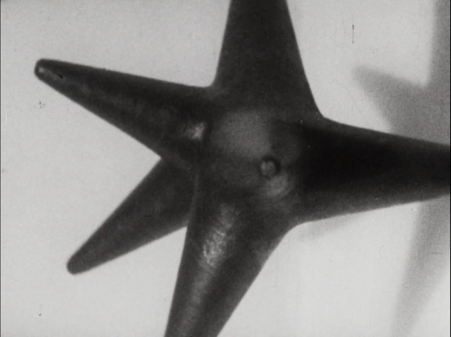

In the Gryphon Group’s promotional pamphlet for the film, composer Dlugoszewski affirms the film’s intersensory attempts to bewilder. “Every sound in the score is the image of bewilderment […] the ear will be shocked into listening […] bewilderment is glorious […]”, she proclaims (qtd. in Lewis 14). Intent upon an effect of bewilderment, Menken makes no effort to provide a holistic interpretation of Noguchi’s art. In place of establishing shots of the studio space or more distanced, objective shots of the artworks, she piles up alternating, differently textured points of view. In one shot, Noguchi’s collision of materials and his interest in suspension are hinted at through a set of spokes embedded into a sculpture (Fig. 3). In another, Menken’s camera speeds up the shadowed form of one of Noguchi’s interlocking sculptures before it travels down again, roving over the same piece in daylight (Fig. 4).

Figure 3 (above): Suspended materials. Figure 4 (below): Patterns of light and shadow.

Visual Variations on Noguchi. Kino International, 2007. Screenshots.

In Sitney’s view, “Menken’s rapid sweeps, tilts and pans affirm her presence and her maneuvering at the expense of Noguchi’s objects” (27). As with other body-based interpretations of Menken’s cinema, Sitney (like Brakhage) reduces the film’s expressive movements and its technical gestures to Menken’s human movements, enacted while filming on location (23). Via Flusser’s discussion of moving tools, I think we can suggest other possibilities that are more consistent with Menken’s interest in objects, effects of painterly movement and the non-human expressivity of the cinema.[12]

When the distanced shot of a star-like sculpture appears, Menken suddenly employs three quick cuts to move our vision closer and closer towards this object. Here, Menken’s editing and rapid camerawork creates a stuttering, jittery assertion of “the specificity of film as a medium” (Shana MacDonald) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Mechanical vision in Visual Variations on Noguchi. Kino International, 2007. Screenshot.

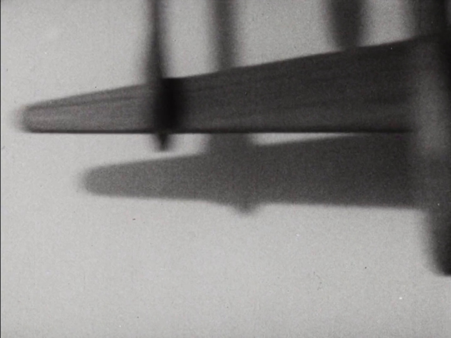

A similarly jarring, machine-like effect occurs later on in the film. Focusing on a pointed sculpture, mounted high up on a wall, the camera begins to flagrantly sweep across the surface of Noguchi’s art object. Panning left to right, Menken repeats the same technical gesture of sweeping this object six times. Combined, the camera’s sweeping motion together with Menken’s rapid-fire shot repetition lends the film a mechanical, stuttering effect—as if the camera’s vision were caught, jittering back and forth, in a loop (Fig. 6).[13]

Figure 6: Sweeping gestures in Visual Variations on Noguchi. Kino International, 2007. Screenshot.According to Menken, her intention in making the film was to capture “the flying spirit of movement” that she saw as being contained in Noguchi’s art, dynamically transitioning sculpture into cinema (Ragona 31). Following the film’s mechanical stuttering over a sculpture, Visual Variations on Noguchi gives way to a darkened passage of abstract shapes. In these moments, Noguchi’s three-dimensional sculptures transform into flying streaks of white light, moving in all directions across a flattened black frame. Any sense of spatial orientation is lost as is any distinct sense of what is being filmed. Transforming Noguchi’s art into ephemeral shapes and light patterns, Menken simultaneously transforms cinema into a kind of abstract painting.

For all their discontinuity, Menken’s “variations” on Noguchi’s art are not completely random. Guided by the shapes, lines and edges of the different artworks, she employs the handheld Bolex to retrace the contours of Noguchi’s sculptures, sweeping upwards, downwards and horizontally. Alternatively, her camerawork lingers on the different surfaces of Noguchi’s art or chases after fleeting patterns of light and shadow. At the close of Visual Variations on Noguchi, Menken fixes on a rotating geometric sculpture, attached to the ceiling. Against the clanging sounds of the timbre piano, footsteps, bells and whispered words, the camera begins to move downwards. With a hard cut, Menken shifts the film’s focus from the metallic to the pocketed surface of a wooden sculpture, reversing the camera’s previous direction by moving upwards. With another cut, the rounded stone top of another piece is then introduced. As the camera moves closer and closer towards this object, the rounded top dims to a darkened blur. After speeding down another marbled surface, the film’s images cut out completely while Dlugoszewski’s cacophonic score continues.

In her closing shots, Menken repeats many of the same technical gestures and formal patterns that organise the film: sweeping camera movement; close-ups that attend to fragments, contours, edges and materiality; textural shifts between wood, metal and stone; unexpected shot transitions; blurred imagery; lapses into abstraction and discordant audiovisual conjunctions. Uninterested in exploring human interiority, Menken took to filmmaking to rework the “world of objects”, including art objects (Flusser 34). In her Visual Variations on Noguchi, she activates the art “object’s performative potential” for the cinema (Ragona 25). Through the mediated freedom afforded by her newfound moving tools (the handheld Bolex, editing and later sound) she transforms Noguchi’s art into new, bewildering, cinematic combinations: sweeping, stuttering, flying by turns.Invented Events, Reaching Gestures: At Land

“To understand how we think, we must look at the hands”, Flusser insists (32). In Gestures, Flusser draws a number of evocative parallels between the movements of the hands and “inner” acts of comprehension (perception, curiosity, evaluation). For Flusser, the “concrete movement of the hands” indicates how the world is “taken in, grasped, intended and manipulated” (32). Thinking through the hands also inflects Maya Deren’s cinema. Whereas Menken intuitively explores, responds to and transforms Noguchi’s art, oftentimes embracing a “machinic viewpoint” or pockets of abstraction (Guo), Deren relies on a much more calculated approach: the “creation of a relationship between separate times, places and persons” (“Cinematography” 222). For Deren, cinema’s purpose is to achieve a thoughtful, preplanned concept (made possible through the manipulation of film form). The “entire burden of a film—both the filming and the editing—rests upon the initial conception and planning”, she asserts of her third (and her second fully completed) film, At Land (Essential Deren 184). In At Land, Deren’s return to the hands and her manipulations of the natural world take precedence over portrayals of interiority.

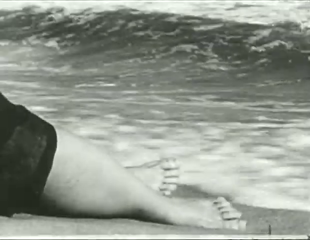

As Deren glosses At Land: “If one may speak of a theme it is the effort of the individual to relate oneself […] to a fluid, apparently incoherent universe” (Essential Deren 247). Described as an “inverted Odyssey” and a “mythological voyage of the twentieth century”, Deren’s reworking of the mythic quest begins with an elemental focus on the sea (Essential Deren 205). In the film’s opening shots, the camera watches the ocean’s waves break three times before following the waves to the shore. At the very edges of where the ocean meets dry land, a woman appears (played by Deren herself, in one of her last onscreen appearances as her own film protagonist). The woman of At Land has been washed ashore, “thrown up on the beach by the sea” (Essential Deren 183). Waves gush over her, covering her body in sea foam. Through the water, we catch glimpses of pale skin, her darkened hair and dress.

Creating what she likes to call the “invented event”, Deren then starts to combine her filming of the body in nature with a moment of cinematic artifice (“Cinematography” 222). Employing reverse motion, she creates the impression of the waves drawing back over the woman, flowing backwards like a streaming cloth. Juxtaposing the woman’s stasis with the waves’ impossible, backwards movement, the waves’ reversal leaves the woman’s feet exposed on the foreshore (Fig. 7).[14]

Figures 7 and 8: Deren’s “invented event”: an intertwining of nature and the body with cinematic artifice (above); moving from the sea to being at land (below). At Land (Maya Deren), 1944. In the Mirror of Maya Deren (Martina Kudláček), 2001. Zeitgeist Films DVD, 2004. Screenshots.

While conceived as the film’s “sole continuous element”, it is worth noting that the unnamed, female protagonist of At Land is typical of Deren’s efforts to evacuate subjective or personal expression from the cinema (Essential Deren 205). As Sarah Keller affirms, for “all their attention to Deren’s figure” (with Deren herself featuring in key roles), in Deren’s 1943–1946 films she strived to “de-emphasize the self”, a tendency that she would take further in later projects (Maya Deren 85).

Following the “invented event” of the reversing waves, the film cuts to a close-up on the woman’s face (Fig. 8). In this shot, the woman appears still partially damp from the sea—her hair is coated in grains of sand. When we next see the woman, she is lying further up the beach where she appears fully dry. Through reverse motion and more subtle slippages in space, time and mise en scène, Deren shifts her protagonist further and further away from her oceanic origins. The first of her “impossible journeys” in the film is staged as an environmental “passage from one element to another” (Fischer 194; Essential Deren 183).

As Annette Michelson and Maureen Turim detail, Deren’s fierce rejection of abstraction together with her belief in the careful planning and execution of “film form” were at odds with the aesthetic rhetoric of the times—namely, those artists, critics and filmmakers who believed “in improvisation and the directly expressive gesture” (Turim 77–8; see also Michelson, “Poetics and Savage Thought” 22).[15] In her post-war polemic for film as a combinatorial art, Deren points to the anagram as a source of inspiration.[16] Extending the logic of the anagram to film, she suggests that it is through the filmmaker’s control, manipulation and arrangement of parts (i.e., shots) that a greater whole can be created—an idea, a feeling, an entire “emotional and intellectual complex” (Anagram 25). Advancing the filmmaker as an artist and cinema as a unique space-and-time art, Deren is quick to caution against art for one’s own personal expression. The “most enduring works of art create a mythical reality”, she asserts, “which cannot refer to one’s own personal observations” (Anagram 24; emphasis added).

Animated by principles of sympathy and association, Deren’s filmmaking is driven by the urge to make connections between shots, spaces and ideas (the sea and the land, nature and artifice, the exterior and the interior, the human and the non-human). Given her efforts to de-emphasise the individual, I find it telling that she often invokes non-human imagery to convey the cinema’s magical, revelatory powers: the ocean, trees, plant life, animals or the magnification of a “mountainous, craggy landscape” (“Cinematography” 219).[17] In An Anagram, she cites a lyricism that is inherent in slow-motion footage of birds. Similarly, the incremental motion of a plant (moving towards the sun) reveals an “integrity of movement” that only “the most patient and observant botanist could have […] suspected” (47). Such images are just the beginning, however. This is because the camera here functions as “an instrument of discovery rather than creativity”. The camera furnishes the artist-filmmaker with one “basic element” (reality) that needs to be creatively embellished (“Cinematography” 219). For Deren, cinema always involves the imaginative and the technical mediation of the world. More particularly, the “magic ability” of the cinema to foster “new realities” results from the combination of three different layers: the reality before the film camera; the artist-filmmaker’s intervention in reality and the “art-instrument” (technology) through which their “imaginative manipulations” must be realised (Essential Deren 202; Anagram 48).

With another cut, the protagonist is situated still further away from the sea. Relocated to a pebbled environment, she is filmed lying on her back, looking skywards. A flock of birds passes overhead, prompting the woman to respond to their flight across the frame with a reaching movement. Her gesture continues into the next shot, where Deren reveals a large piece of driftwood beside her. Contorting her body and limbs, the woman pulls herself upright, looking around her new environs. As Keller observes, Deren’s frequent shots of looking signal “a shift in attention, movement or direction—often revealing an unexpected, impossible element just offscreen” (Maya Deren 95–6). From the driftwood, the woman begins to climb—a climb that will see her and the film’s setting shift from the beach to a large banquet hall (replete with elegantly dressed partygoers, a glistening chandelier and a game of chess). As Deren recounts, she designed the driftwood sequence as a “statement on the distance between two worlds” (Essential Deren 184). Using the same piece of driftwood, she and her camerawoman (Hella Heyman) filmed at different levels to elongate the woman’s climb.[18] Through the technical embellishment of slow motion, also, Deren sought to create the “illusion of a tall, natural ladder” and the suggestion of a “long and important climb” (Essential Deren 184).

Returning to Flusser’s comments on the thoughtfulness of the hands, it is important to note how looking in At Land is complemented by Deren’s emphasis on various manual gestures. The driftwood climb, for instance, begins with a shot of the woman’s hand, moving up into the frame from the pebbled ground below. After the woman’s fingers close around narrow branches, she pulls herself into view. Peering out through gaps in the driftwood, Deren creates a densely layered shot, visually correlating the woman’s fingers with the surrounding branches (Fig. 9 and 10).

Figures 9 and 10: Deren’s “invented event”: the driftwood climb and shots of the hands (above); from the driftwood climb to the banquet hall (below). At Land. Zeitgeist Films, 2004. Screenshots.

At the mid-point of her climb, the woman’s fingers clasp onto thicker branches. Here, Deren plays on the driftwood’s “ladderlike construction”, setting the woman’s climb against the horizon (Essential Deren 184). Filmed against the sky, the movement of the woman’s outstretched hand carries over into the following shot. In place of hands curling over branches, Deren cuts to a shot of the woman’s fingers, curling over the edges of a white tablecloth (Fig.10).Reflecting on the driftwood sequence, Deren posits that there is nothing “meaningful about any of [its] shots individually […] the meaning of each [shot] depends […] organically, upon its position in the whole” (Essential Deren 184–5; emphasis added). To create the organic sequencing of At Land, Deren relies on match-on-action editing, together with the movement and gestures of her protagonist. This involves her “beginning some simple movement in one place and concluding it another” (Essential Deren 205). For Turim, in At Land, Deren develops a new “action language” of “filmic expression” in which “each new act is registered by [the] female protagonist […] as wide-eyed witness” (93). More than just a mere witness to her surroundings, though, the protagonist adapts to the film’s kaleidoscopic shifts by way of the hands. Oftentimes, this adaptation occurs through Deren’s inclusion of quite literal shots of her hands, her arms and fingers in the film.

According to Flusser, the hands express a “powerful, active gesture”, exerting their own “force in the world” (35). Enacting a manual mode of perceiving and comprehending (the gesture of “grasping”), hands open up “a channel through which certain things flow and others are excluded” (35). Climbing into the banquet hall, the woman reorients her body to the new horizontal reorganisation of the film’s mise en scène. Ignored by the party guests around her, she uses her hands and her elbows to propel herself forwards, moving slowly towards the end of the table where a game of chess is in progress. As with other flagrant points of geographic transition in the film, Deren initiates a new trajectory of movement through the woman’s outstretched hand.

Reflecting on her work, Deren singles out At Land as the project that helped her understand the “capacity of film to manipulate Time and Space” (Anagram 5). As the woman crawls hands-first, Deren begins to intercut between shots of her inside the banquet hall and shots of her in a different time and space, crawling through thick forest greenery. (This is the first suggestion there might be many “Mayas” in the film.) When she emerges from the foliage, she reaches out. Her gesture is cut short by a cut back to the banquet hall, however. Inside the banquet hall, the woman has reached the end of her tabletop journey. At the end of the table, she watches on as a chessboard comes to life. Its pieces move about the board without any human players.[19] A pawn is knocked from the board only to fall into another exterior location: the waterfall of a rock formation. To signal the next portion of the woman’s journey and to make another environmental transition, Deren begins with footage of the woman’s hand, filmed gripping onto the rocks where the pawn has just fallen (Fig. 11).

As Flusser asserts, “hands move almost constantly” for “hands are one of the ways we human beings are in the world” (34; emphasis added). Describing the thoughtful interactions of the hands, he suggests that hands will either make a hasty retreat from a situation (a gesture that indicates fear or revulsion) or that hands will “insist on meeting” the world. When hands meet the world, he writes, the grasping hands “touch […] with the fingertips”; they actively follow an object’s outline or “feel its weight […] pass it from one hand to the other (think it over)” (35). In At Land, the protagonist uses her hands to think, feel and grasp her way through a range of shifting situations. Oftentimes she is filmed touching different surfaces to help ease herself into another new environment (the waterfall’s edge, the wooden pillar outside a shack in the forest). Inside the film’s “relativistic universe”, animate and inanimate objects appear then disappear (a cat, a chess piece). The film’s “locations change constantly and distances are contracted or extended” (Essential Deren 205). Oceans can reverse or solid rock transform into a large, wooden structure. One man (Philip Lamantia) mutates into a series of men (Parker Tyler, John Cage, Alexander Hammid) as the protagonist walks. As the woman makes her way through different environs (the foreshore, the driftwood climb, the banquet hall/forest, the waterfall, the forest shack, the cliffs, the dunes), Deren returns to imagery of the woman’s hands touching, clasping, reaching and grasping.

Figure 11: Hands as a means of thinking and environmental transition in At Land.

Zeitgeist Films, 2004. Screenshot.

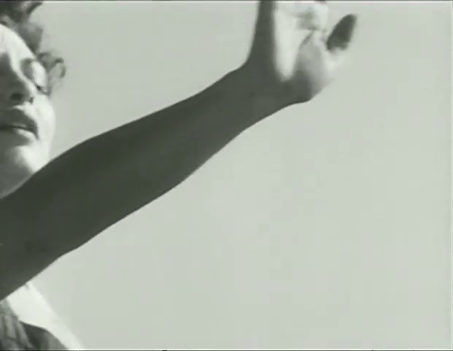

An emphasis on the woman’s reaching and grasping hands is particularly evident in the cliff sequence. Here, Deren stages another “invented event” that intertwines real-world elements (the wind, the sky, the craggy textures of the cliff) and the body in nature with heightened, cinematic artifice. After passing through the multiple doors of the forest shack, the protagonist next appears on top of a cliff. Filmed in slow motion and from a low angle, she looks down, always searching for a path forward. Clouds pass by as she feels her way down the rocks. Cutting to a shot of the woman’s hand reaching out against the sky, Deren creates the illusion of her being suspended in mid-air (Fig. 12). When she falls onto an opposing cliff and begins sliding down, her hand is the last element to leave the frame.

Figure 12: Reaching gestures in At Land. Zeitgeist Films, 2004. Screenshot.

Never passive, the woman of At Land adapts to each of the film’s landscape shifts and its unexpected shot transitions. She meets the film’s unstable world with “open arms, fingers spread, surfaces facing one another” (Flusser 34). Towards the conclusion of At Land, she begins to collect and cradle large stones in her arms, replacing each of the stones as they fall. Her enigmatic task is interrupted by the introduction of another game of chess, played at the edges of the sea by a blonde and a dark-haired woman (Heyman).[20] In another moment of mutation, the two players are suddenly relocated in front of her. With both players seated before her, the woman uses her hands to adapt once more. She reaches out, starting to stroke the players’ hair. Seizing her moment, she snatches the white queen piece from the board, running away from the game and its players with both hands held aloft.

As Ute Holl rightly observes, Deren’s cinematic “odysseys are not […] the progressive formational journeys of heroes” but “circular movements” (85). To close the “active, fluid universe” of At Land, Deren intercuts between shots of the protagonist running through all the film’s previous locations and the many “Mayas” from earlier scenes (Essential Deren 205). In these moments, Deren inventively weaves the film’s different space-time and environmental fragments together through the manual gestures of her protagonist. In succession, we see shots of the woman running, holding the queen; collecting stones; clutching her hair; gripping a cliff; on top of the white banquet table; and, finally, holding onto the large piece of driftwood (the object that ushered in her passage between worlds). Having returned to the site of the sea and its foreshore, Deren leaves the many journeys of At Land open-ended. In the film’s final shot, the camera trails after the woman as she leaves a set of footprints behind her in the sand. Running off with the stolen queen, her future remains ambiguous. Her landscape could keep mutating infinitely.

In his general theory of gestures, Flusser calls for gestural analysis to focus its attention not “on the fact that a freedom expresses itself in the gesture” but “on how it expresses itself” (175). Describing the mediated freedom of technical gestures, he writes: “what makes a movement a gesture is not that it is free but that a freedom is ‘somehow’ expressed in it. And ‘somehow’ means ‘by means of some technology’” (175; emphasis added). From different perspectives but in complementary ways, both Deren and Menken used their “moving tools” during the mid-1940s to transform human gesture through the cinema (Flusser 166). “I intended [the film] almost as a mythological statement”, Deren remarks of At Land. The “girl in the film is not a personal person, she is a personage” (qtd. in Kudláček). Similarly, when Menken began to incorporate shots of her own hands, body or shadow into her filmmaking, she remained uninterested in using cinema to explore inner states of feeling. As Visual Variations on Noguchi attests, her manual approach delights in a cinematic manipulation and mechanical repatterning of objects and environments, oftentimes bordering on the abstract. In At Land, by contrast, Deren (a staunch supporter of the “primacy of the mimetic-figurative” in film) employs the hands (onscreen) to signal a thoughtful, gestural means of adaptation (Michelson, “Poetics” 30). Hands also provide Deren (offscreen) with a creative and technical means of manipulating film form. Through her emphasis on the hands, she is able to piece together the film’s different surfaces, shots, spaces and scenes, “opening up to the future” (Flusser 34–5). Running counter to the gestural rhetoric that surrounded abstract expressionism or their avant-garde film contemporaries, Deren and Menken set in motion the possibility of a desubjectified, gestural cinema. For Deren and Menken, the hands of the artist-filmmaker form part of the cinematic machine.

Notes

[1] This term derives from P. Adams Sitney who identifies the “handheld, somatic camera” as a “formal matrix” across Menken’s work. For Sitney, this matrix bonds the film’s images to the “movements of the filmmaker” (23).

[2] Across her career, Menken engaged with a number of contemporary art movements (European modernism, Fluxus and pop art). Many of her works play on an intermedial merger between film and painting, sculpture or other art objects. For a complete filmography of Menken (1945–65) see Ragona.

[3] While not the principal focus of this article, it is thought provoking to consider the implicit “masculinisation” of gesture that circulated around the abstract expressionists. On the gendering of this art movement and how it shapes depictions of the male painter in film see Bukatman (311). As Ragona observes, it was because of her different engagements with art, film and animation that Menken came to reject “abstract expressionist concerns with the specificity of paint and canvas” (23).

[4] Here, I am invoking the English translation of Flusser.

[5] Freedom is a complex notion in Flusser’s thinking. It does not signal “free will” but intentionality, orientation and (potential) agency. Furthermore, it is circumscribed by historic, social and technological factors. As Bram Ieven explains, relating Flusser’s notion of freedom to his thinking on “technical images”: “Freedom is […] not understood as something independent from apparatuses, but as the ability to rule the apparatuses instead of letting the apparatuses rule us. […] in a world that is always mediated by different media, one can still be free […] if one uses media to successfully orientate oneself in the world” (Ieven). In the context of this article, I am interested in the gestural orientation of Deren and Menken’s filmmaking: not expressions of an individualistic, creative “freedom”.

[6] Menken continued making abstract art into the early 1950s, exhibiting her art at New York galleries such as Betty Parson’s Gallery. In 1950, her exhibition at Betty Parson’s was followed by one of Jackson Pollock’s.

[7] Stephanie Herfield makes this explicit: “Just as […] Pollock improvised the actions of painting through the release of his body and the immediacy of his sensations, Menken improvised kinetic reactions through mindful contact with her environment” (91).

[8] On Brakhage’s bodily descriptions of Menken’s camerawork see Sitney (23). As Hart details, Brakhage’s perceived “oneness” between body and camera in Menken was actually far more intrinsic to his own experimental film aesthetic (42–3).

[9] Contra Rosenberg, Flusser argues that “the painted painting” (the final image) is a “stiffened, frozen gesture”. It is the “painting to be painted” that counts (70).

[10] At the time, Menken was collaborating with Noguchi on a Merce Cunningham and John Cage production of the ballet The Seasons.

[11] Dlugoszewski is credited with pioneering the unusual sounds of the timbre piano. Played from the inside, the piano’s strings are activated by the hands or by devices such as mallets or combs (Lewis 6–7).

[12] Writing during the 1960s, Parker Tyler also perceived a non-human, rhythmic energy governing Menken’s cinema. Her filmmaking exhibits a “nervous, somewhat eccentric rhythmic play”, he writes, achieved via the “camera itself [as] a moving agent” (160).

[13] Similar “jittery” effects occur in Menken’s Go Go Go (1964), which combines time-lapse techniques with stop motion. For a complementary reading of Menken’s reworking of her surroundings see Guo.

[14] The beached woman of At Land has been likened to a mermaid, loosely connected to Deren’s interest in the sea, other worlds and underwater life. In The Mirror of Maya Deren (Martina Kudláček, 2001) recounts Deren’s New York bedroom as being adorned with a luminous sea painting, shells and other oceanic objects.

[15] By “film form I mean the creation of something which could not be accomplished by any other media” (Deren, Essential Deren 164). Refuting art as an individualistic or personal endeavour, Deren proffers a “procession of indistinct figures”, “hoods of the chorus”, “formal patterns of ritual and destiny” (Anagram 18).

[16] Non-linear form, structure and “play” manifest—quite literally—in Deren’s ludic table of contents. For a discussion of Deren’s conception of film form see Turim.

[17] In “Magic is New” (penned the same year as An Anagram), Deren praises cinema for its “magic ability to make even the most imaginative concept seem real” (Essential Deren 202). On magic as it connects with Deren’s realism see Keller (“Frustrated Climaxes”).

[18] For the driftwood climb, the woman was filmed climbing from a high angle, with a low-placed camera and, finally, at a very low angle.

[19] This is the sequence of At Land that Menken animated for Deren. Menken also collaborated on Deren’s The Very Eye of Night (1958).

[20] Deren refers to the two players (human doubles for the chess pieces) as the “white” and the “black”. On the significance of chess in Deren’s film see Keller (Maya Deren 93) and Turim (93–4).

References

1. Beugnet, Martine. “Touch and See? Regarding Images in the Era of the Interface.” InMedia, vol. 8, no. 1, 2020, pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.2102.

2. Bukatman, Scott. “Brushstrokes in CinemaScope: Minnelli’s Action Painting in Lust for Life.” Vincente Minnelli: The Art of Entertainment, edited by Joe McElhaney, Wayne State UP, 2009, pp. 297–321.

3. Deren, Maya. An Anagram of Ideas on Art, Form and Film. Alicat Bookshop Press, 1946.

4. ----. “Cinematography: The Creative Use of Reality.” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings, edited by Gerald Mast, Marshall Cohen and Leo Braudy, Oxford UP, 1992, pp. 216–27.

5. ----. Essential Deren: Collected Writings on Film, edited by Bruce McPherson, Documentext, 2005.

6. ----, director. At Land. 1944.

7. ----, director. The Very Eye of Night. 1958.

8. Dlugoszewski, Lucia. the poetry of natural sound. 5 players; t-pno, everyday sounds, film score for Visual Variations on Noguchi, 1953.

9. Fischer, Lucy. “The Eye for Magic: Maya and Méliès.” Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde, edited by Bill Nichols, U of California P, 2001, pp. 185–204.

10. Flusser, Vilém. Gestures. Translated by Nancy Ann Roth, U of Minnesota P, 2014. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816691272.001.0001.

11. Guo, Caroline. “Work in Progress: Marie Menken and the Mechanical Representation of Labor.” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, vol. 54, no. 12, 2012, www.ejumpcut.org/archive/jc54.2012/GuoMenken/index.html. Accessed 6 May 2022.

12. Hart, Adam. “Extensions of our Body Moving, Dancing: The American Avant-Garde’s Theory of Subjectivity.” Discourse, vol. 41, no. 1, 2019, pp. 37–67. https://doi.org/10.13110/discourse.41.1.0037.

13. Herfield, Stephanie. “Seeing Moving: The Performance of Marie Menken’s Images.” Art in Motion: Current Research in Screendance/Art en movement: Recherches actuelles en ciné-danse, edited by Franck Boulégue and Marisa C. Hayes, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015, pp. 89–101.

14. Holl, Ute. Cinema, Trance and Cybernetics. Translated by Daniel Hendrickson, Amsterdam UP, 2017. https://doi.org/10.5117/9789089646682.

15. Ieven, Bram. “How to Orientate Oneself in the World: A General Outline of Flusser’s Theory of Media.” Image & Narrative, vol. 6, Feb. 2003, www.imageandnarrative.be/inarchive/mediumtheory/bramieven.htm. Accessed 6 May 2022.

16. Keller, Sarah. “Frustrated Climaxes: On Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon and Witch’s Cradle.” Cinema Journal, vol. 52, no. 3, 2013, pp. 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2013.0018.

17. ----. Maya Deren: Incomplete Control. Columbia UP, 2015.

18. Krauss, Rosalind E. The Optical Unconscious. MIT Press, 1996.

19. Kudláček, Martina, director. In the Mirror of Maya Deren, 2001. Zeitgeist Films, 2004.

20. Lewis, Kevin D. “The Miracle of Unintelligibility”: The Music and Invented Instruments of Lucille Dlugoszewski. 2011. University of Cincinnati, PhD thesis.

21. MacDonald, Scott. “The Filmmaker as Visionary: Excerpts of an Interview with Stan Brakhage.” Film Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 3, 2003, pp. 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2003.56.3.2.

22. ----. “Women’s Experimental Cinema.” Women’s Experimental Cinema: Critical Frameworks, edited by Robin Blaetz, Duke UP, 2007, pp. 360–2. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822392088-017.

23. MacDonald, Shana. “Visual Variations on Noguchi.” Senses of Cinema, vol. 50, March 2009, www.sensesofcinema.com/2009/cteq/visual-variations-on-noguchi/. Accessed 6 May 2022.

24. Menken, Marie, director. Go Go Go! 1964.

25. ----, director. Visual Variations on Noguchi. Gryphon Productions, 1945. Avant-Garde 2: Experimental Cinema 1928-1954, Kino International, DVD, 2007.

26. Michelson, Annette. “Poetics and Savage Thought: About Anagram.” Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde, edited by Bill Nichols, U of California P, 2001, pp. 21–47.27. ----. “Film and the Radical Aspiration.” 1966. Foco, 2016–2021, www.focorevistadecinema.com.br/FOCO8-9/michelsonradicaldveng.htm. Accessed 6 May 2022.

28. Ragona, Melissa. “Swing and Sway: Marie Menken’s Filmic Events.” Women’s Experimental Cinema: Critical Frameworks, edited by Robin Blaetz, Duke UP, 2007, pp. 20–44. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822392088-002.

29. Rosenberg, Harold. “The American Action Painters.” 1952. Abstract Expressionism: Context and Critique, edited by Ellen G. Landau, Yale UP, 2005, pp. 189–198. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt32bk1z.29. Accessed 6 May 2022.

30. The Seasons, choreography by Merce Cunningham, performance by Merce Cunningham, members of Ballet Society and students from the School of American Ballet, 18 May 1947, Ziegfeld Theatre, New York City, New York.

31. Sitney, P. Adams. Eyes Upside-Down: Visionary Filmmakers and the Heritage of Emerson. Oxford UP, 2008.

32. Sheehan, Rebecca A. American Avant-Garde Cinema’s Philosophy of the In-Between. Oxford UP, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190949709.001.0001.

33. Stein, Gertrude. “Doctor Faustus Lights the Lights.” Last Operas and Plays, edited by Carl Van Vechten, John Hopkins UP, 1995, pp. 89–118.

34. Turim, Maureen. “The Ethics of Form.” Maya Deren and the American Avant-Garde, edited by Bill Nichols, U of California P, 2001, pp. 77–102.

35. Tyler, Parker. Underground Film: A Critical History. Da Capo Press, 1995.

Suggested Citation

Walton, Saige. “Hands in the Machine: Maya Deren and Marie Menken’s Manual Gestures.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 23, 2022, pp. 32–51. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.23.02

Saige Walton is a Senior Lecturer in Screen Studies at the University of South Australia. She is the author of Cinema’s Baroque Flesh: Film, Phenomenology and the Art of Entanglement (Amsterdam UP, 2016). Her articles on the embodiment of film and media aesthetics appear in journals such as Culture, Theory and Critique, NECSUS, Projections, Paragraph, Screening the Past, Senses of Cinema and the New Review of Film and Television Studies. Her current book deals with the embodiment and form of a contemporary cinema of poetry.