The Image Book: or Penser avec les mains

Martine Beugnet and Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli

Abstract

Drawing inspiration from Denis de Rougemont’s 1936 text Penser avec les mains, Jean-Luc Godard’s most recent film brings together what the Swiss philosopher calls “penser engagé” with his own unique kind of “cinéma engagé.” The Image Book (Le Livred’image, 2018) starts with three image-gestures that punctuate the film: the cropped close-up of the right hand of Leonardo da Vinci’s St. John The Baptist, French illustrator Joseph Pinchon’s drawing of Bécassine with her upwards pointing left hand, and the hands of the filmmaker joining together spools of film at a Steenbeck editing table. Like many other “late” Godard films, The Image Book is a multilayered assemblage of quotations, sounds, music, art and cinematic references. Yet, unlike some of its predecessors, this film questions the monolithic (Occidental) way of seeing the world, including Godard’s younger self. Combining citations from films, works of art and philosophical texts from the Maghreb and the Middle East, the film offers itself as an exercise in “thinking with one’s hands” that results in the unflinching critique of Orientalism in the twenty-first century as well as an imaginative attempt to reach out to, if not join alongside with, the other.

Article

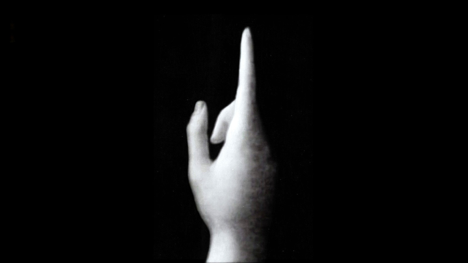

Figure 1: This detail from Leonardo da Vinci’s St. John The Baptist (c. 1513–1519) is the first image we see in The Image Book (Le Livre d’image). Dir. Jean-Luc Godard. Casa Azul Films, 2018. Screenshot.

The Image Book (Le Livre d’image, Jean-Luc Godard, 2018) begins with a simple image: the cropped close-up of the right hand of Leonardo da Vinci’s St. John The Baptist (c. 1513–1519). While da Vinci’s St. John indicates the path from darkness to light (a metaphor for the coming of Christ), in Godard’s rendition the severed hand is overexposed and cast in high-contrast black and white. The iconic hand still points upward, but it now seems to indicate only the path to darkness. It is an indefinite image, followed by a rather enigmatic text: “les maîtres du monde devraient se méfier de Bécassine précisément parce qu’elle se tait” (“The masters of the world should beware of Bécassine, precisely because she is silent”). Like the hand of the prophet, the text is xeroxed, leaving the letters to bleed into one another. With this text, Godard joins hands—da Vinci’s or St. John the Baptist’s with the French illustrator Joseph Pinchon’s rendering of Bécassine—only to point out their qualitatively different gestures. The first, and possibly most famous French female cartoon figure, Bécassine is pictured more than any other image in The Image Book. Like many poor provincial girls in the early years of the twentieth century, she comes to Paris to work as a servant. This stereotypical Breton destined to play the fool, points upwards with her left hand, as if asking to be heard. The gesture of this cartoon figure stands in stark contrast to the delicate sfumato of da Vinci. While the hand of the male prophet is shown from the back of the hand, the silent woman’s hand is rendered from the front. Bécassine raises her hand to ask permission to speak (though as Godard emphasises, she has no mouth). St. John, instead, indicates that his prophecy will lead followers to salvation. It is his gesture that indicates a sort of mastery of the world.

Figure 2: Bécassine in The Image Book. Figure extracted from the cover of the 1991 edition of Bécassine à Clocher les Bécasses, Gautier Langu, illustrator Joseph Porphyre-Pinchon. Although we do not see the figure of Bécassine until the second half of the film, she is the first reference Godard draws on in his voiceover.

The next shot interrupts this initial juxtaposition of image and text, by adding two more hands—the hands of a filmmaker or editor working at a Steenbeck editing table joining together spools of film and disentangling knotted strips of celluloid. The hands are presumed to be Woody Allen’s, a shot already included at the end of Godard’s own King Lear (1987). By showing the handiwork of cinema as working with one’s hands, joining (tangling and untangling) images, Godard attempts to demonstrate how one can begin to “think with one’s hands”. To include a shot of the filmmaker at work is to reaffirm filmmaking as labour and cinema as a thinking with images that cannot be dissociated from physical engagement with the matter of images. Here, as in his four-part Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988–1998), Godard makes us aware of the relationship of the hand to the eye. Initially, that relationship involves shooting but later requires scanning the footage, cutting, and gluing one frame to another.[1] For a long time, editing (as it involved the manual handling of film stock) was considered a woman’s job and therefore, as Karen Pearlman has pointed out, was considered secondary and devalued. From his classic defence of montage in “Montage, mon beau souci” to The Image Book, however, Godard debunks the image of the editor as mere operator. Even in the era of digital dematerialisation, Godard’s practice has remained close to bricolage, aiming to retain, as one of the captions in Histoire(s) du cinéma proposes, a “marge d’indéfini”—room for the unplanned.[2]

In this article, we explore Godard’s thinking with images as a thinking with one’s hands. Drawing inspiration from Swiss philosopher Denis de Rougemont’s 1936 text Penser avec les mains, Godard brings together a “penser engagé” with his own unique kind of “cinéma engagé”. He challenges other filmmakers, contemporary audiences and film critics, who, as film critic A. O. Scott has discussed, are “unable to shake [themselves] out of [their] sunny, shallow, American mental habits and succumb to the master’s gloomy Gallic wit and intellectual intransigence”.

To see nothing but “historical trauma, dead writers, and old movies” (as A. O. Scott claims he does) and understand critical thought as pessimism is a form of intellectual laziness. The Image Book challenges us to not indulge in such conceits, for the juxtapositions are too jarring—Orientalist fantasies are placed next to footage taken by ISIS. This is not simply some cinephilic exercise in piecing together fragments of obscure films from the historical archives, nor is it the kind of citational cinema that gestures toward a particular style without engaging its ideological premises. Godard reminds us that these same hands that create worlds, images, and forge relations, can also dismiss them with a stroke of a pen, or destroy them in an instant. Life is fragile, but, as James Baldwin points out, if we want to live we cannot afford to indulge in destruction: we cannot mistake thinking for pessimism.[3]

By reading simple gestures in terms of binary oppositions (creative or destructive), we end up mirroring the Cartesian (Platonic) fracturing of the pensive mind from the emotional or reactive body. For de Rougemont, the advent of Western modernity actualises this split between the hand and the mind, manual and intellectual labour, with catastrophic results. Seen from the vantage point of the twenty-first century, the hands included in Godard’s montage do not always gesture towards humanity’s common future. They often signify a continuing and growing divide between those who impose their law and those who are subjected to it. Deceptively similar to Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) where the workers mindlessly labour below the modern city, Godard’s invocation of the hand is often connected to action and labour. But unlike Lang who associates the master of the universe or owner of the factory (corporation or empire) with the brain, Godard associates the hand with mastery and the potential to destroy or act violently.

Figures 3 and 4: Unlike these images from the end of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis,Godard’s use of the hand

is not meant to signify the working class. Rather, it is with the hand that the philosopher must think.

Metropolis. Dir. Fritz Lang. Universum Film (UFA), 1927. Screenshots.

There is, however, no redemptive vision, no third component of the heart or spirit that makes each of these three distinct parts function more efficiently, contently, or humanely—as in the case of Metropolis, where the final subtitle reads, “Heads and hands need a mediator. The mediator between the head and the hands must be the heart.” Instead, for Godard, like de Rougemont, the “literates” who cast themselves in the role of mediators and thinkers have become “brains without hands” (“cerveaux sans mains”) (Rougemont 147). They are nothing more than dilettantes, “the good minds, the professors, for whom thought is an art of pleasure, an inheritance, a liberal career, or a well-placed capital” (147).[4]

Godard, however, does not exclude himself from the kind of critique that de Rougemont levels at those intellectuals who have lost the capacity to engage with the object of their thinking. While The Image Book may be most closely related to Histoire(s) du cinéma and Film socialisme (2010), Here and Elsewhere (Ici et ailleurs, 1976, with Jean-Pierre Gorin and Anne-Marie Miéville) casts a long shadow over all of these films. Here and Elsewhere was the result of an aborted film, designed to support the Palestinian uprising in Jordan (1970). Shooting took place a few months before Black September (“Aylūl Al-Aswad”, also known as the Jordanian Civil War) wherein many of the people Godard and Gorin filmed had died. The film that finally emerged six years later was Godard’s initial attempt at using montage to juxtapose images from the Middle East with those of the West. But Here and Elsewhere also stands as Godard and Miéville’s unflinching self-critique of an overthought project. Marred by a priori concepts and clichés, the project demonstrated an inability to see and to listen to the Palestinian people whose plight was presumably the subject of the film. Miéville’s voiceover commentary in Here and Elsewhere describes their undertaking as propaganda, putting words into people’s mouths according to a preconceived script. Along with the recitation of images from Here and Elsewhere comes the memory of Godard’s own acknowledged failure at engaging with the reality at hand—a failure that relegates him, like other Western thinkers and artists, to the status of what de Rougemont believed were ineffectual or complicit bystanders.The core argument in Penser avec les mains is that Western modernity has separated thought and culture from hands and work. In this process, humanity lost what de Rougemont calls a “common measure”, that is, the capacity to live together.[5] To lose the practice of the “common measure” is to open the door to totalitarianism where only a few self-proclaimed masterminds rule over the mass of rural and urban labourers. In the name of abstract notions like “progress” and “cultural evolutionism”, the bourgeois order subjects all forms of artisanal handiwork and manual labour to a logic of “rationalism” under the banner of a collective history that legitimises the power of the few (41).[6] Such asymmetrical systems of governance and visions of collective history perpetuate radical disparities in wealth, access to resources, and standards of living that become increasingly more difficult to justify. In response to the many ensuing crises of bourgeois capitalism, authoritarian regimes present themselves as emergency measures needed to cure an “ailing social body” that has become unable to function for the good of the masses—be they, in de Rougemont’s eyes, the fascism of Nazi Germany, the Soviet socialist system, the cutthroat capitalism of the United States, or equally, the various military dictatorships that emerged throughout the Middle East, Latin America and Asia (158). Having (literally) lost their grasp of the real, thinkers (“brains without hands”) prove incapable of meaningful political action: they become redundant, hostages to systems of power.[7] To regain a pertinent presence, de Rougemont argues, thinking needs to “manifest itself” (146–7). Inscribed within the term “man-ifest” is the hand—la main (146–7).

Aware of the shrinking place of critical cinema in relation to contemporary film, Godard equates his activity and handiwork as an artist and filmmaker with Bécassine’s status and role. With a quivering voice, he plays the aged fool, asking to be heard. This is no act of resignation, instead we argue that Godard has maintained his own form of militancy—one that focuses on the hand’s potential to destroy, but also on the capacity to touch, encounter, create and engage so as to make radical change. This gesture does not have the same political commitments as the Popular Front nor the militant cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Rather, it endures as a radical practice of thinking—one that, as de Rougemont puts it, is not designed to simply reflect, record, witness or denounce, but to create as a revolutionary act.

In the remainder of this article, we would like to focus on how these three gestures—St. John the Baptist’s symbolically laden indexical finger, Bécassine’s call for attention, and Godard’s act of joining strips of film through montage—and how they help us to unpack some of the complex political and philosophical themes that are prevalent in Godard’s later work. Similar to many other “late” Godard films, The Image Book is a multilayered assemblage of quotations, sounds and music, and historical, artistic and cinematic references.[8] Yet, unlike some of its predecessors, this film directly takes up the question of Orientalism in the twenty-first century. Echoing Edward Said, as Godard puts it in The Image Book, “the world is not interested in Arabs or Muslims”, it is only interested in the politics of representing Islam in neo-imperialist terms. When the West looks at the East, the act of representation is thus even more clearly associated with violence that, as Gilles Deleuze has so forcefully argued, does not involve thinking (Difference 131). Instead, it repeats predetermined ideas and their given images. Responding to philosophical generalisations, like the Kantian a priori, Deleuze writes: “we may call this an image of thought [but it is also] a dogmatic, orthodox or moral image”, and thus, it evades any encounter with otherness (131). Yet it is only through such an encounter with the other that we are forced to think (139).

Questioning the monolithic (Occidental) way of seeing the world, Godard inserts citations from films, works of art and philosophical texts from the Maghreb and the Middle East that may be unfamiliar to Western audiences. Thus, he radically departs from the kind of approach adopted by his younger self—an approach that led to the disastrous Palestinian film project of 1970. We argue that in The Image Book Godard’s thinking with his hands starts by questioning the role of gesture in the dissemination of ideas. More specifically, as we are told in The Image Book, Godard asks us to consider the gesture of editing as opposed to the more imperial gesture of representation that “almost always involves violence toward the subject of representation”. Inseparable from the act of representation, the gesture of the pointing index finger is polyvalent, it commands, projects, and redirects the viewers’ attention along an imaginary line. While not a symbolically universal gesture for religious transcendence, da Vinci certainly presents St. John’s pointing finger as one. According to Charles Sanders Peirce, the index, icon and symbol are functional operations that together produce and systematise meaning (104–15).[9] But once extracted from its religious context the finger caught in the act of pointing now becomes indexical (pointing upwards), iconic (it resembles pointing), and symbolic (in its association to the act of pointing) all at once, questioning where the distinct semiotic components of depicting, describing and indicating begin and end. We see the image as pointing but there is no referent other than the pointing. Can we still assume that this severed hand points toward the coming of Christ? Does it point to the film to come, or direct us to the text that questions whether or not we can read Bécassine’s silent gesture as an image?

Art historian Ernst Gombrich reads the gesture of pointing as a sign of dominance and mastery akin to the cinematic gaze that both commands and directs an audience’s attention (394). By pointing to images, events and situations, film often situates figures, actions and landscapes within a narrative. However, as Ludwig Wittgenstein argues, we should not confuse the act of pointing, indexicality or “ostension” that gives a name to a figure, place or event with “ostensive definition” (1, § 6, 4). The act of naming indicates the mastery of language, but is not the same as knowing the figure, the place captured on film, nor understanding an event that has transpired.[10] The Image Book contemplates this gap between pointing at an “other”, capturing this other as an image, and being able to know the other. “The masters of the universe”, as Godard calls them, may name the other, but the other still eludes them. For Wittgenstein, such acts of naming always involve the finger, whether an actual indicator (like the teacher in the classroom or St. John the prophet) or a metaphorical index (an affective image that allows us to speculate on what someone knows or how they feel) (1, § 34, 12).

Da Vinci’s iconic finger is associated with many types of mastery: the male prophet’s teaching of religious transcendence as painted by the Renaissance master that is now cast in black and white, indicating a binary perspective: between light and darkness; between the truth or faith and heresy: the act of naming and being named; masters and their followers or servants. But by extricating the gesture from its (dogmatic or moral) context, Godard asks us to think if a gesture can ever stand by itself. A gesture not only establishes a relation, but it must always be addressed to an “other” and invisible “you”, as Godard made so clear in his Histoire(s) du cinéma. Returning to Emmanuel Levinas’s “I–thou” equation, Godard asks us once again to understand how a gesture like pointing can be both a sign of an interpersonal encounter, and one that displaces the addressee to what Kaja Silverman calls “the category of the third person”—the depersonalised other, stripped of their subjectivity in a game of mastery (9).

At first, it is the figure of Bécassine that seems to encompass this category of the third person. If St. John The Baptist appears as a fragment, Bécassine is, initially, a mere textual invocation, talked about in the third person (as if to designate the cleavage that separates the speaking subject from the object of its speech). And when she eventually appears, she is the figure with no mouth, a body that does not speak, a non-speaking subject. Bécassine is thus doubly excluded from the realm of discursive power-knowledge, which Godard, as the mostly unseen voiceover, appears to command. Like Bécassine he too has become provincial, living in the small Swiss hamlet of Rolle, though she (as the billions of the world’s poor) had no choice but to leave her province. As a servant, working for a wealthy Parisian family, Bécassine arguably stands as an ancestor of the gilet jaunes, the representative of a scorned provincial underclass. But she is also a much-debated figure of national and cultural identity and separatism: embraced by some as a positive model, including as a female and as a national character, and abhorred by others, for whom she is an embodiment of provincial close-mindedness.

Yet, for all the lowly and contentious status she holds in visual culture, Bécassine raises her finger. In an era of image production and circulation dominated by monolithic messages and the rules of the economy of attention, she is asking to be heard. Initially, Bécassine is out of place: a comic book character in a film populated by shocking cinematic visions of human oppression and war. The style of her drawing abrades with Godard’s colourist experimentations. In Marshall McLuhan’s terms, this is an encounter of hot and cold media (297). Pinchon’s drawings belonged to the “clear line” school of the comic book, where colour is used in blocks of solid, uniform shades. In The Image Book, Godard demonstrates his penchant for layering, high contrasts, grainy, low-definition effects, and his resolute unwillingness to make any colour corrections that would fix or stabilise images. He aims to accentuate the effects of colour saturation and bleeding. It is also difficult to imagine a greater divide than that which separates Bécassine as a comic book figure, a representative of popular culture, from the depiction of St. John the Baptist by a Renaissance master painter, one who has come to be known as the epitome of classical, high art. Whereas Renaissance painting still features prominently as part of a Western dream of cultural dominance, Bécassine is the very definition of the local and parochial.

Figure 5: The Image Book: Bécassine, detail. This double image of Bécassine, now in close-up,

appears toward the end of the film, signifying her multiple roles and relations to both rural or parochial France and to Orientalist fantasies about the other. Casa Azul Films, 2018. Screenshot.

Figure 6: The Image Book: La Marsa. This image shot on location by Fabrice Aragno,

Godard’s director of photography, serves as a visual metaphor linking Godard’s images to those of the nineteenth- and twentieth-century European Orientalists. Casa Azul Films, 2018. Screenshot.

But soon, she too becomes colourised in the film, her reworked, doubled and painterly appearance turning into a graphic transition from the previous scenery and landscapes of the images of the Arab-speaking world. The film juxtaposes the bright blue, saturated red and yellow footage taken in the Tunisian coastal town of La Marsa with nineteenth- and turn-of-the-century artworks of André Derain, August Macke (View of a Mosque, 1914) Edouard Manet (The Balcony, 1868) and Eugène Delacroix (The Moroccan Notebook, 1832), among many others. The juxtaposition of footage shot on location in Tunisia by Fabrice Aragno (the director of photography) and with works of art coming from a range of different art movements, hint at Godard’s realisation that he too may be participating in his own Orientalist fantasy about the Middle East. Each image shares a vibrant use of colour that borders on the abstract. Godard’s selection of Orientalist art seems to rely exclusively on the more abstract or unfinished works, sketches, and watercolours found in Delacroix’s notebooks instead of his more imaginary, grandiose and violently erotic paintings like The Death of Sardanapalus (1827) and The Odalisque (1814). These sketches from everyday life exhibit what the German Expressionists—a few of whom would also turn to Orientalist themes after a visit to Tunisia and Algeria in 1914—called “pure colourisation”. Blocks of blue, red and gold are used to depict the light, figures and textures of the Maghreb. The Image Book draws a visual connection from the earlier Romantic French and English Orientalists to the more abstract work of Der Blaue Reiter. Travel to North Africa has often been understood as a demarcation between the early abstract expressionist works of August Macke and Paul Klee, and their later more idiosyncratic engagement with colour as an object of study with its own meaning and purpose. Godard indirectly refers to Klee’s seminal trip to Tunisia by recalling his famous declaration that, “colour has taken possession of me […] colour and I are one” (qtd. in Partsch 20). Godard instead reflects: “Nous parlions d’un rêve, et nous demandions comment, dans l’obscurité totale, peuvent surgir en nous des couleurs d’une telle intensité (“we were talking about a dream, and how, from total obscurity, colours of that intensity can appear in us”). Godard’s words can be heard over a call to prayer which starts in total darkness with a prolonged fade to black that is followed by the distorted image (both in terms of colour and scale) of Macke’s A Glance Down an Alley(1914). The bright colours of Macke’s painting are then matched to what looks like a fashion design sketch for women’s clothing, overwritten with the word “start” (“commence”), a reminder of the connexion that Orientalism creates between art and the luxury trade (or “commerce”).

Figure 7: The Image Book. Godard inserts images from advertising to connect the discourse of Orientalism

to that of global capital, particularly tourism. Casa Azul Films, 2018. Screenshot.

The works of Delacroix and Macke are yet again resituated alongside the pixelated images of torture taken from Ossama Mohammad and Wiam Bedirxan’s Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait (Ma’a Al-Fidda, 2014), and the equally colourful images of Arabs massacred in the desert. This work of colourisation and digital distortion points to the West’s contradictory relation to the Middle East. On the one hand, the stunning work of digital colourisation points to an awakening of something other than an Orientalist vision. On the other hand, it points back to a history that reduces the Arab world to scenery and landscapes, and much worse, to the site of torture and atrocity. Hence if the colourised and doubled figure of Bécassine can serve as a transition, it is also because she cannot speak for herself, she can be filled with colour and inscribed in a discourse. In a title card Godard repeats Gayatri Spivak’s most famous essay (“Can the Subaltern Speak?”) replacing the word “subaltern” with “Arab”. Similarly, as Said argues, the Arab world has been both feminised and exoticised under Western eyes. At the same time, this world is demonised in post–Cold War geopolitics that seek to reimagine the new world order in binary terms—East and West, North and South, Occident and Orient, Man and Woman, self and other, etc.[11] The multiple figures of Bécassine, instead, reminds us that empire requires a double operation of exploitation: an exploitation of the poor, and working classes at home who pay with their labour to build the machinery of empire, and the subjugation (if not eradication) of indigenous peoples whose livelihoods and resources are extracted in the process. Even though she is cast in opposition to recurrent images of mastery and superiority, her raised indexical finger stands as a silent surrogate for an “I”, a request for attention in the here and now.Bécassine’s is a small gesture of resistance, persistence, and insistence. While we can say that this gesture speaks, it certainly does not speak in the same manner as the militant images taken by either revolutionary filmmakers or ISIS videographers. It is tempting to associate Godard’s found footage practice with the notion of the “poor image” that, as Hito Steyerl argues, creates “a circuit, which fulfils the original ambitions of militant and (some) essayistic and experimental cinema [or] creating an alternative economy of images, an imperfect cinema existing inside as well as beyond and under commercial media streams”.[12] Poor images have become a by-word for the democratisation of image production. Steyerl goes so far as to define the circulation, appropriation and compression of these low-resolution or copied images as the triumph of “lumpen proletarian in the class society of appearances”. Against the flourishing business of copyrights and the privatisation of artistic and intellectual content, advocates of this new iteration of the imperfect image embrace piracy. In the process, value shifts away from the original property or work of the master to the traces that an image leaves as part of its historicisation, degradation, and dissemination to shared networks. But what exactly is shared has once again become an abstraction, mere shifters that are copied and degraded so that they end up blurring the roles of consumer and producer.

Many of the images in The Image Book are indeed pirated, but they are not poor in the sense that they are reduced to overused or overdetermined shifters, no longer pointing to definitive subjects of representation. Godard rejects equating the digital to some universal form of communication that has the ability to translate and simplify all former modes of expression rendering them all “accessible” on a singular “shared” platform. Instead, he reminds us that even the digital begins with the hand and its five fingers (the five digits that make up the hand). The digital is not the result of some automatic or machinic process, rather it involves the work of many hands. Alongside all labour-intensive actions that make computational media operational are multiple acts of deception (the manufacturing of dreams, clichés or outright lies) and the trick of obfuscating the intricate and deeply political material and their technological infrastructures. But between the moment of their capture and that of their dissemination, there lies a space for the filmmaker as editor and colourist to intervene and experiment with digitised and digital images alike. This calls attention to both the meaningless, unedited flow of poor images, and the numbing power of the “visuel”, what Serge Daney has described as the circulation of images that “obey the same rules as spectacle, advertisement, a video game or a military fair” (147).[13] We want to stress that Godard’s intervention cannot be reduced to some exercise in formalism, nor a sophisticated critique of the impact of the “visuel” on our ability to blind ourselves to the realties we see before us or experiences within ourselves. Instead, it is a reflection on the fact that the poor, the underrated, the politically disenfranchised, and most of the Arab world, do not have the same weapons of destruction or representation as the so-called “masters of the universe” who “liberate” and occupy Middle Eastern territories. But the occupation of these territories captured by the West cannot continue without oppression, repression and violence, nor without the emergence of resistance that is or will be labelled terrorism by those who control the discourse. For Godard, terrorism, itself has become an art akin to what James Scott calls “the weapons of the weak”. Reflecting on the schizophrenic manner in which the West looks at the Arab world, Godard turns to Egyptian writer Albert Cossery, quoting at length from his novel Une ambition dans le désert (1984): “Here in Dofa, people throwing bombs seems normal […] it is the only way they can express their revolt against the brutal methods used by the governments […] As far as I am concerned, I will always be with the bombs […] Do you think men in power in today’s world are anything other than blood-thirsty enemies?”[14]

Figure 8: The Image Book. This is the third image we see in the film, one recycled from

Godard’s King Lear (1987) that seems to picture Woody Allen’s hands. Casa Azul Films, 2018. Screenshot.Contrary to the gesture of pointing, the gesture of editing is a hands-on process, one that acknowledges that acts of deception (“the sleight of hand”) and the violence of representation cannot be completely decoupled from the act of meaning-making. Yet the hands of the director working at the editing table also suggest the possibility of a different mode of production of meaning, one that is founded on joining rather than pointing or begging for attention. Of the three gestures, this is the most complex one because it draws together the handiwork of the editor with the name of the auteur. Whether these are the hands of Godard or those of Allen is of no importance. It is the gesture itself, the skilled handling of the material that matters. There is nothing nostalgic to Godard’s repeated featuring of analogue equipment such as the Steenbeck table. He is no luddite.[15] Throughout his long career, he has continuously embraced technological innovation, using new technical possibilities to test the limits of audiovisual expression against the grain of an impoverished mainstream practice. The Image Book serves as yet another an example of how Godard transfers the analogue into the digital, transforming it in the process. Godard has proven himself to be exceptionally resistant to the lure of automatism—what Vilém Flusser calls the transformation of the filmmaker into a “functionary”—questioning instead the growing annexation of human gestures by automated protocols that frame and normalise not only the production of images, but our very access to the visible (Towards 27; Beugnet). Flusser also stresses the importance of handiwork, of grappling with matter, where the material to be shaped into an object serves as a third, quasi-dialectical, component (Towards 27). Without it, he argues, the left and right hand are condemned to “mirror each other”. Hence the act of bringing them together only confirms their irreconcilable difference (Gestures 32–3).

Figure 9: The Image Book: shot from Al-Ha’mun (Wanderers of the Desert)byNacer Khemir 1984.

In the fifth section of the film (“The Central Region”) Godard cites Khemir’s film trilogy, focusing on his use of colour. In this instance, he refers to the enigmatic hand gesture of the young Saharan woman who has been trapped in her father’s house just before she too disappears into the desert. Casa Azul Films, 2018. Screenshot.

Using an extract from Nacer Khemir’s Al-Ha’mun (Wanderers of the Desert, 1984), Godard seems to visualise this impossible symmetry. In Al-Ha’mun, a fifteen-year-old Saharan woman raises her two hands in the air in a gesture reminiscent of surrender or perhaps a sign of her own captivity in her father’s house. But she then brings her left and right hand together, completely rotating her body to her left side, only to repeat or mirror the same gesture on her right. This performative gesture ends with her pressing to her heart a mirror that suddenly appears in the palm of her hands. While profoundly beautiful, the gesture is just as mysterious as the young woman who performs it. Like Bécassine, she remains silent, dressed in a colourful outfit that points to her own provinciality or marginality. Her attire places her somewhere between the history of the lost domain of the Arab empire that stretched from Damascus to Granada and the imaginary world of fairy tales like Arabian Nights.[16] If, as Flusser suggests, abstract concepts often derive from the movements of the hand, as when “to grasp” or “to get” become synonymous to comprehending, then what are we to make of those gestures performed in Al-Ha’mun that reflect a symmetrical combination of opposites as well as the very image of the mirror itself (Gestures 32–3)?For Flusser, the creative gesture must converge on “an obstacle, a problem, or an object”, aiming to produce something that can eventually be offered to others. Thus, the “gesture of making” is always one of presentation, and as such it is also, always a political gesture (Gestures 46–7). Here Flusser’s argument resonates with theories of analytical montage as a process of excluding, but also connecting, bringing together incompossible images to create new meaning. Challenging Flusser’s premise and its reconciliation of opposites, The Image Book,however, demonstrates how gestures can be repeated and images recycled so that, like signs, their meaning is recast through new juxtapositions. Also, conscious of the kind of political gesture that results from a practice of editing out, silencing and erasing the voices, expressions, ideas and cultural heritage of others, Godard cultivates an art of gluing and joining where encounters with difference proliferate: a confrontation of non-chronological juxtapositions that seem to come apart as much as they are surprisingly brought together. Other images appear almost out of nowhere, suppressing, covering, or losing the indexical traces that allow us to situate them in the first place.

Godard’s later filmmaking practices have been compared with Aby Warburg’s Mnemosyne Atlas project, since, like Warburg’s iconological method, Godard’s montages are composed of a diverse range of gestures and imagistic patterns occurring in cinema and other media (Natali 169–83; Michaud; Latsis). But unlike Warburg’s fixation on anthropocentric gestures, Godard explores overdetermined cinematic tropes. If images of hands and hand gestures intermittently appear throughout The Image Book, then so do those of trains, of weapons, and acts of violence. Yet beyond notions of survivance (nachleben) or of the “symptom image” (the unearthing of visual culture’s repressed), Godard’s work is an attempt at engaging with the present-day catastrophe, counterpointing the effect of emptied out, iconic Western visual representation as short-hand for the communication of universal modes of expression and conventional meaning (Didi-Huberman).[17] Thinking with one’s hands therefore cannot be compared to historicising, identifying, or fetishising images: it does not just produce historic events out of splicing memories and archival images to be perused, absorbed or fast-forwarded on video. Rather, it is a way of acting upon the given, whether that be an image or a sequence of images, an ideology or a set of beliefs.

While in The Image Book we may be watching the hands of another filmmaker, it is Godard’s voice that we hear reflecting: “Il y a cinq doigts et cinq sens, et cinq parties du monde. Oui les cinq doigts de la fée. Tous ensemble ils composent la main” (“There are five fingers, and five senses, five parts of the world. The fairy’s five fingers. Together they make up the hand”). Accordingly, The Image Book is divided into five unequal sections—the largest one being called “La Région centrale” (“The Central Region”) comes at the end, making up the film’s second half. A pun on both the Middle East and Michael Snow’s 1971 film by the same name, La Région centrale is cited at the beginning of “The Central Region”, questioning our sense of perspective or grounding. Yet, unlike Snow, this does not comprise of a continuous image that seems to defy gravity. Rather, it is full of abrupt cuts, references to imperialist narratives and Western fantasies about the Arab world from Joseph Conrad’s Under Western Eyes (1911), Alexander Dumas’ L’Arabie heureuse (1860), and Cossery’s Une ambition dans le désert that are juxtaposed to lines from Said and Spivak, and images from various films and moving images from the Arab-speaking world.

Figure 10: The Image Book: shot of the coast from La Marsa. Images from La Marsa are clearly set apart from others since they emphasise deep blues, bright yellows and reds, focusing on both the desert and the sea as borderless spaces. Casa Azul Films, 2018. Screenshot.

Commenting on Godard’s use of montage in Here and Elsewhere, Deleuze stresses the importance of the interstice, the space between the images and words that the filmmaker choses in a given sequence. For Deleuze, Godard does not seek to unify or to “associate” disparate images, rather he emphasises the gaps between them (Cinema 2 171–2). At the same time, montage creates new meaning, by establishing new relations, its meaning must be internal to the image not the external world. Any resemblance that may surface on account of the “perpetual reorganization” of images is measured against their “irreducible difference” (Cinema 2 234–5). Similarly, in his preliminary remarks on the film, Serge Daney insists on the import of the “et/and” in the title:

propaganda means—for a filmmaker—using the image of others to make this image say something else than what the others are saying in it. So, what is at stake is the engagement of a filmmaker as a filmmaker. For it is in the nature of cinema (the delay between the time of shooting and the time of projection) to be the art of here and elsewhere. What Godard says, very uncomfortably, and very honestly, is that the true place of the filmmaker is in the AND. A hyphen only has value if it doesn’t confuse what it unites. (qtd. in Kretzschmar and Krohn)[18]

The “et/and” makes us aware that there are always many hands at work (the many operators involved) in the construction of an image. Such an awareness interrupts the act of representation that is so caught up in the gesture of pointing at a subject while obscuring its own subjectivity in the process.

In addition to the obvious asymmetries in terms of length of each of the sections, and in translated French and untranslated Arabic, Persian, Italian, German, Greek, Hebrew and other languages, there is a complex soundtrack starting with Godard’s multi-track voiceover that often seems to repeat, to be amplified or muffled, to be close by or distant, and a returning soundtrack of musical phrases from Mieczysław Weinberg, Avro Pärt, Paul Misraki, Giya Kancheli, Jean Sibelius, among many others. Musical phrases such as the opening (moderato con moto) of Weinberg’s Sonata for Violoncello and Piano Quintet, Opus 18 (1944) punctuate key moments in the film, giving it a sense of rhythm and dramatic emphasis, but not a sense of coherence. Similar to the practice of editing that links and unlinks images, the film’s soundtrack does not offer empathetic sound that amplifies the image’s emotional significance, nor does it provide a clear authorial voice. Godard’s voice is heard throughout, but it is a frail, aged voice that ends in a coughing fit, prefacing the film’s very last shot, an excerpt from Max Ophüls’s Le Plaisir (1952), in which the aging, masked dandy dances towards his death. Yet, if this is a dance of death, it has been rehearsed many times in Godard’s “late” films. Unlike Ambroise (the masked dandy), Godard is not trying to disguise his advanced age, rather he is constantly reflecting on it and how he must confront “a time that is out of time”. Yet, this is not the only mark of time, as we hear the feedback noise from Godard’s old microphone.[19] If the true place of the filmmaker is in the in-between, the “and” that separates and joins “here and elsewhere”, then as a filmmaker reaching the end of his life, Godard finds himself face to face with the most radical “elsewhere”. In doing so, he appears freer than ever to talk about the seemingly irreconcilable realities of the world at hand.

Godard’s own voice is both pensive and fragile; it is on the move, constantly travelling in space through surround sound and multichannel tracks that give the voice a ghostly quality. The voice is, however, not consistent. It is altered in frequency and amplitudes, and appears to be speaking over other voices and sounds as much as it is drowned out by other voices from a variety of films, musical scores, sound effects, and Miéville. Furthermore, the use of musical cues does not instruct viewers on how to properly emotionally respond to images. More often than not, there is a disjuncture between what we see and what we hear. Michel Chion calls this effect “phantom audio-vision”, which he describes as “a mysterious effect of ‘hollowing out’ audiovisual form: as if audio and visual perceptions were divided from each other instead of mutually compounded and in this quotient another form of reality, of combination, emerged” (125–6). For instance, in an oversaturated copy of Napoléon (Sacha Guitry, 1955) we see Napoleon’s army defeating the Ottomans in Egypt, only to hear someone dramatically call out for a retreat, which is followed by another voice who casually explains: “Christianity is the refusal to know oneself”. This voice, that cuts short the urgent call for retreat, is also interrupted by the honking of a car horn. With all this complex textured and layered sound, Godard still opens up a space for silence, and the silenced. His most obvious reference can be found in the persistent use of fade to black, which has become standard shorthand for the cinematic index of silence or emptiness. The black screen is also an index in itself, it points to nothing or no thing: it is a gesture toward the unknown, the other, the indefinite and the possibility of thinking as a form of self-overcoming, of becoming other. Moments of silences, the black screen and the sounds of the technical devices point to various encounters, the joining and rupture of audiovisual materials.

Neither a collector’s plundering of the cinematic archive, nor the application of a “pathos formula” (even if there is, in parts, an effect of that), the juxtaposition of images, texts, sounds, voices and music works as a connecting of the disconnected—one that relies on the differences and preserves the space between images. Though Godard, like Bécassine, can never escape his own Western, provincial position and ways of seeing, The Image Book is still a joining of hands so to speak: an attempt at an encounter with Arab filmmakers, intellectuals, philosophers, artists, and musicians. In contrast with the act of pointing or indexicality, this is a gesture towards the other, the indefinite and the possibility of thinking as a form of self-overcoming.

Notes

[1] For a reflection on film and the relation of eye to hand, see Emmanuelle André, L’Œil détourné, in particular Chapter 2, which focuses on Godard’s Adieu au language (Goodbye to Language, 2014). See also André, “Seeing through the Fingertips”.[2] “Ne va pas montrer tous les côtés des choses. Garde-toi une marge d’indéfini” (Histoire(s) du cinéma, 1.a).

[3] In a 1963 interview given with Kenneth Clark, Baldwin was asked whether he was optimistic or pessimistic about the future of African Americans. Baldwin responded: “I can’t be a pessimist because I am alive. To be a pessimist means you agree that human life is an academic matter.” He then proceeded to turn the question of America’s future to white America. Those who invented and rely on white supremacy are the obstacle to any optimistic future. Such understanding as to why white America indulges in such destruction is key to opening up a future.

[4] The original reads: “les fins lettrés, les bons esprits, les professeurs, pour lesquels la pensée est un art d’agrément, un héritage, une carrière libérale, ou un capital bien placé”. All translations from French are by Martine Beugnet.

[5] As de Rougemont is a Christian the aspiration for living together encompasses not only the capacity to fill the gap that separates us from others but also each one of us from God.

[6] Here, de Rougemont also cites Auguste Comte: “Of necessity, the living will always be governed by the dead, and progressively more so” (“Les vivants seront toujours et de plus en plus gouvernés nécessairement par les morts”).

[7] This is a situation de Rougemont denounces anew in the preface to the 1972 edition of the book ([Nouv. éd.] 7–15).

[8] The film’s dense archival basis was researched and collected in collaboration with the filmmaker’s coproducers, Fabrice Aragno, Jean-Paul Battagia and the French film theoretician Nicole Brenez. For a discussion of the “late” Godard see Fletcher (59–72).

[9] See also Doane (128–52).

[10] See part § 2 of Wittgenstein’s The Philosophical Investigations, where he discusses learning to master words and § 31 where he argues that the person who learns the name “has already mastered a game” (15).

[11] By the end of the Cold War a new discourse emerged concerning the reformation of the world order, transforming from a binary model to one dominated by Western Capitalism, shifting from ideological to religious contentions (Huntington; Fukuyama).

[12] See also Marks.

[13] Reflecting on his experience of the televised coverage of the war in Iraq, Daney talks about his “étrange prise de conscience que la guerre obéirait aux mêmes lois du spectacle et de la publicité qu’un jeu vidéo ou qu’un salon militaire” (147).

[14] In the novel, the Sheik Ben Kadem attempts to bring the poor emirate of Dofa, eclipsed by its powerful oil-producing neighbours, on the international scene, by simulating bomb attacks blamed on an invented terrorist organisation—a stratagem that soon spirals out of control.

[15] In a one-minute trailer entitled Nos espérances, created for the Jihlava International Documentary Film Festival in 2018, Godard films himself handling a mobile phone, using his index to travel through some of the content of The Image Book at an accelerated speed. At the end, a portrait of the filmmaker, dishevelled and smiling, briefly appears on the diminutive screen. While the interfacing gesture is both filmed and playfully diverted from its, by now, largely automatic usage, Godard portrays himself as a quirky apparition, inhabiting the small device like the spirit of the genie in Aladdin’s lamp.

[16] The dress of the characters in Al-Ha’mun are not Tunisian. As Nacer Khemir reflects: “In the same way that I tried to recreate an image of a city in the eleventh century, giving it the Arab-Islamic touch of those centuries, I also tried to recreate a human group that could have and—at least presumably—would have inhabited that splendour and framework. The process of pasting (collage), and combining things, happened over several stages, and this pertains to architectural as well as human constructions” (Nacer Khemir 257; trans. Beatrice Dumin).

[17] In one of the conclusions to L’Image-temps, Gilles Deleuze observes that “Les nouvelles images n’ont plus d’extériorité (hors-champ), pas plus qu’elles ne s’intériorisent dans un tout: elles ont plutôt un endroit et un envers, réversibles et non superposables, comme un pouvoir de se retourner sur elles-mêmes. Elles sont l’objet d’une réorganisation perpétuelle où une nouvelle image peut naître de n’importe quel point de l’image précédente” (347). (“The new images no longer have any outside (out-of-field) any more than they are internalized in a whole; rather, they have a right side and a reverse, reversible and non-superimposable, like a power to turn back on themselves. They are the object of a perpetual reorganization, in which a new image can arise from any point whatever of the preceding image” (Cinema 2 265)).

[18] This unpublished text was apparently written by Serge Daney as a preface to a screening of Here and Elsewhere.

[19] See Amy Taubin’s interview with Fabrice Aragno, “The Hand of Time.”

References

1. André, Emmanuelle. L’Œil détourné. Mains et imaginaires tactiles au cinéma. De l’incidence, 2020.2. ---. “Seeing through the Fingertips.” Indefinite Visions. Cinema and the Attractions of Uncertainty,edited by Martine Beugnet, Allan Cameron, and Arild Fetveit, Edinburgh UP, 2017, pp. 273–88. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474407137-018

3. Anonymous. The Arabian Nights. Edited by Kate Douglas Wiggin and Nora A. Smith, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1909.

4. Baldwin, James, and Kenneth Clark. “Conversation with James Baldwin.” From the Vault, WNDT, 24 May 1963. openvault.wgbh.org/catalog/V_C03ED1927DCF46B5A8C82275DF4239F9.

5. Beugnet, Martine. “Touch and See? Regarding Images in the Era of the Interface.” InMedia, vol. 8, no. 1, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4000/inmedia.2102.

6. Caumery. Bécassine à Clocher-les-Bécasse, Gautuer Langu, 1991.

7. Chion, Michel. Audio-Vision: Sound on the Screen. Translated by Claudia Gorbman, Columbia UP, 1990.

8. Conrad, Joseph. Under Western Eyes. Methuen & Co, 1911.

9. Cossery, Albert. Une ambition dans le désert. Gallimard, 1984.

10. Daney, Serge. La Maison cinéma et le monde. 4. Le Moment “Trafic”, 1991–1992. P.O.L., 2015.

11. Delacroix, Eugène. The Death of Sardanapalus [La Mort de Sardanapale]. 1827. Louvre, Paris.

12. ---. Moroccan Notebook. 1832. Private collection.

13. Deleuze, Gilles. Cinéma 2. L’Image-temps. Éditions de minuit, 1985.

14. ---. Cinema 2. The Time-Image. Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta, The Athlone Press, 1989.

15. ---. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton, Columbia UP, 1994.

16. Didi-Huberman, Georges. L’Image survivante. Histoire de l’art et temps des fantômes selon Aby Warburg. Collection de Minuit, 2002. https://doi.org/10.4000/questionsdecommunication.7290.

17. Doane, Mary Anne. “The Indexical and the Concept of Medium Specificity.” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 1, 2007, pp. 128–52. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-2006-025.

18. Dumas, Alexander. L’Arabie heureuse. Michel Lévy Frères, Libaire-Éditeurs, 1860.

19. Fletcher, Alex. “Late Style and Contrapuntal Histories: The Violence of Representation in Jean-Luc Godard’s Le Livre d’image.” Radical Philosophy, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 59–72.

20. Flusser, Vilém. Gestures. Translated by Nancy Ann Roth, U of Minnesota P, 2014. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816691272.001.0001.

21. ---. Towards a Philosophy of Photography. Translated by Anthony Mathews, Reaktion Books, 2000.

22. Fukuyama, Francis. The End of History and the Last Man. Free Press, 1992.

23. Godard, Jean-Luc, director. Goodbye to Language [Adieu au langage]. Wild Bunch, 2014.

24. ---, director. Film socialisme. Vega Film, 2010.

25. ---, director. Histoire(s) du cinéma. Canal+, 1988–1998.

26. ---, director. King Lear. The Cannon Group, 1987.

27. ---. “Montage, mon beau souci.” 1965. Filmfilm, filmfilm.eu/post/87977465683/montage-mon-beau-souci-par-jean-luc-godard-cahiers-du. Accessed 14 June 2022.

28. ---, director. The Image Book [Le Livre d’image]. Casa Azul Films, 2018.

29. Godard, Jean-Luc, Jean-Pierre Gorin, and Anne-Marie Miéville, directors. Here and Elsewhere [Ici et ailleurs]. Gaumont, 1976.

30. Gombrich, Ernst. “Ritualized Gesture and Expression in Art.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences, Vol. 251, no. 772, 1966, 393–401. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1966.0025.31. Huntington, Samuel P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order. Simon and Schuster, 1996.

32. Ingres, Jean-Auguste-Dominique. Grande Odalisque. 1814. Louvre, Paris.

33. Khemir, Nacer, Nacer Khemir: Das Verlorene Halsband der Taube. Edited by Bruno Jaeggi and Walter Ruggle, Verlag Lars Müller/Trigon Film, 1992.

34. ---, director. Wanderers of the Desert [Al-Ha’mun]. France Média, 1984.

35. Kretzschmar, Laurent, and Bill Krohn. “Daney on Ici et ailleurs: A Newly Unearthed Text and Some Known Ones.” Kino Slang, 17 Jan. 2009, kinoslang.blogspot.com/2009/01/preface-to-here-and-elsewhere-by-serge.html. Accessed 29 June 2021.

36. Lang, Fritz, director. Metropolis. Universum Film (UFA), 1927.

37. Latsis, Dimitrios S. “Genealogy of the Image in Histoire(s) du Cinéma: Godard, Warburg and the Iconology of the Interstice.” Third Text, Vol. 27, No. 6, 2013, pp. 774–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2013.859480.

38. Leonardo da Vinci. St. John The Baptist. 1513–1519. Louvre, Paris.

39. Levinas, Emmanuel. Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority. Translated byAlphonso Lingis, Martinus Nijhoff, 1979.

40. Macke, August. A Glance Down an Alley [Blick in eine Gasse in Tunis]. 1914. Ziegler Collection, Stadtishes Museum, Mulheim, Germany.

41. ---. View of a Mosque [Blick auf eine Moschee]. 1914. Bonn, Kunstmuseum, Private Collection.

42. Manet, Edouard. The Balcony [Le balcon]. 1868. Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

43. Marks, Laura U. “Poor Images, Ad Hoc Archives, Artists’ Rights: The Scrappy Beauties of Handmade Digital Culture.” International Journal of Communication, vol. 11, 2017, pp. 3899–916.

44. McLuhan, Marshall. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. MIT Press, 1994.

45. Michaud, Philippe-Alain. Aby Warburg et l’image en mouvement. Macula, 1998.

46. Mieczysław Weinberg, composer. Sonata for Violoncello and Piano Quintet, Opus 18. 1944.

47. Mohammad, Ossama, and Wiam Bedirxan, directors. Silvered Water, Syria Self-Portrait [Ma’a Al-Fidda]. Arte France Cinéma, 2014.

48. Natali, Maurizia. “Warburg et Godard.” Cinéma art(s) plastique(s), edited by Pierre Taminiaux and Claude Murcia, L’Harmattan, 2004, pp.169–83.

49. Ophüls, Max, director. Le Plaisir. Compagnie Commerciale Française Cinématographique (CCFC), 1952.

50. Partsch, Susanna. Paul Klee, 1879–1940. Taschen Books, 2003.

51. Pearlman, Karen, director. Woman with an Editing Bench. Ronin Films, 2016.

52. Peirce, Charles Sanders. “Logic as Semiotic: The Theory of Signs.” Philosophical Writings of Peirce, edited by Justus Bucher, Dover, 1995, pp. 104–15.

53. Rougemont, Denis de. Penser avec les mains. Albin Michel, 1936.

54. ---. Penser avec les mains. Nouv. éd., Gallimard, 1972.

55. Guitry, Sasha, director. Napoléon. Court et Long Métrages (C.L.M.), 1955.

56. Scott, A. O. “Godard Looks at Violence and Movies.” The New York Times, 23 Jan. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/01/23/movies/review-the-image-book.html.

57. Scott, James C. Weapons of the Weak: The Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance. Yale UP, 1985.

58. Serge Daney. “Kino Slang,” translated and published by Laurent Kretzschmar and Bill Krohn, 17 Jan. 2009: https://kinoslang.blogspot.com/2009/01/preface-to-here-and-elsewhere-by-serge.html. Accessed 29 June 2021.

59. Silverman, Kaja. “The Dream of the Nineteenth Century.” Camera Obscura, vol. 17, no. 3, 2002, pp. 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1215/02705346-17-3_51-1.

60. Snow, Micheal, director. La Région centrale. Canadian Filmmakers Distribution Centre, 1971.

61. Steyerl, Hito. “In Defense of the Poor Image.” E-Flux Journal, no. 10, Nov. 2009, www.e-flux.com/journal/10/61362/in-defense-of-the-poor-image.

62. Taubin, Amy. “The Hand of Time.” Film Comment, vol. 55, no. 1, 2019, www.filmcomment.com/article/the-hand-of-time.

63. Wittgenstein, Ludwig. Philosophical Investigations. Translated by G.E.M Anscome, Basil Blackwell, 1958.

64. Warburg, Aby. Mnemosyne Atlas. 1924–1929.

Suggested Citation65. Beugnet, Martine, and Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli. “The Image Book:or Penser avec les mains.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 23, 2022, pp. 10–31. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.23.01

Martine Beugnet is Professor in Visual Studies at the Université Paris Cité, a member of the LARCA. She has written articles on a wide range of film and media topics and authored several books on contemporary cinema. The most recent include: L’attrait du flou (Yellow Now, 2017), the co-edited volume Indefinite Visions: Cinema and the Attractions of Uncertainty (Edinburgh UP, 2017), and Le cinéma et ses doubles. L’image de film à l’ère du foundfootage numérisé et des écrans de poche (Bord de l’eau, 2021). She is part of the editorial board of NECSUS and co-directs (with Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli) the Studies in Film and Intermediality at Edinburgh University Press.

Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli is a Professor of Film, Television and Digital Media at the University of California, Los Angeles. She is the author of Unmaking of Fascist Aesthetics (U of Minnesota P, 2001), Mythopoetic Cinema: On the Ruins of European Identity (Columbia UP, 2017), and Digital Uncanny (Oxford UP, 2019). She is currently working on a book with Martine Beugnet entitled The Trouble with Ghosts, and another single-authored book, Resisting Identity: A Case for Public Anonymity. With Martine Beugnet she co-edits the Studies in Film and Intermediality series at Edinburgh University Press.