Re-presenting Histories: Documentary Film and Architectural Ruins in Brutality in Stone

Frances Guerin

Abstract

This article rereads Alexander Kluge and Peter Schamoni’s short film Brutality in Stone (1961) in light of more contemporary scholarly interest in the architectural ruin. This leads to an analysis that challenges or recasts cinematic assumptions about the past. I begin my analysis through attention to Brutality in Stone’s radical strategies of montage, marriage of archival stills and newly shot documentary moving images, merging of real and imagined, past and present, sound and image. These formal strategies are observed through the lens of theories of ruin, Kluge’s own writings on cinema and history, references to the historiography of Nazi architecture, and contemporary theories of ruination in architecture. I then reveal the film as a type of counter-memory, promoting a critical awareness of, rather than espousing an ideologically motivated enthusiasm for the histories and memories of the past as they have been represented in architectural monuments, and cinematic and historical narratives. Specifically, a contemporary reconsideration of Brutality in Stone contributes to rethinking the relationship to the ongoing lessons of German history and its cinematic representation in the contemporary moment. Keeping alive the memories of the past has never been more urgent as we move into a historical moment when memories of the Nazi past are becoming ever dimmer.

Article

Every building bequeathed us by history testifies to the spirit of its builders and of their time, even if it long ago stopped serving its original purpose. (Alexander Kluge and Peter Schamoni, Brutality in Stone)

In 1990, Eric Rentschler looked back at Alexander Kluge and Peter Schamoni’s short film Brutality in Stone (Brutalität in Stein, 1961) as a critique of the present of its making. For Rentschler, the film was an introduction to the political wager of the Oberhausen Manifesto in 1962: “Brutalität in Stein combines the important and inextricably bound impetuses in Kluge’s theory and praxis of film: documentation, authenticity, and experimentation” (33). Specifically, for Rentschler, Brutality in Stone prefaces the concerns of the New German Cinema when it uses an experimental film language to document and expose the discursive fiction of Hitler’s claims for history and reality as they were articulated in Nazi architecture. Effectively, the film seeks to deconstruct the past in an attempt to ensure the reality and material ramifications of National Socialism are unable to be denied (29). Rentschler explains that his understanding of the short, ground-breaking documentary is inseparable from his own historical moment. By 1990, New German Cinema had made visible and “sayable” Germany’s violent past.[1] However, the historical events in Rentschler’s midst as he was writing—namely the fall of the Berlin Wall—would lead to new conceptions of German history and with it, German identity. That is, Rentschler returns to Kluge and Schamoni’s film about the remains and ruins of the unfinished and partially destroyed Reichsparteitagsgelände (Nazi Party Rally Grounds)—built as a monument to the future sovereignty of the Third Reich—at a moment when Germany’s ruptured history was, yet again, in upheaval. Similarly, in 1990, the promised utopia of East German socialism was in ruins, about to be appropriated by what many argued to be capitalist imperialism. This unmentioned historical context might thus be seen as the real question in Rentschler’s article: how can the past be articulated in a moment when its value is rapidly changing thanks to the collapse of, in 1990, the German Democratic Republic? Such a question finds context within an understanding of Alexander Kluge’s conception of history as being defined by a process of rewriting, or revisioning of the past in the present through historical analysis.[2]

If Brutality in Stone’s return to architectural ruins as a rethinking of history has the capacity to reveal aspects of the present of its reception, as well as to re-envision the past from the perspective of that present, then what is the film’s significance today? Influenced by Rentschler’s inquiry, and Kluge’s insistence on making history conscious in the present, I understand Kluge and Schamoni’s film within the current fascination with ruin culture. In addition, I revisit the film to rethink our relationship to the ongoing lessons of German history at a moment when the past is becoming increasingly distant, and memories of that past are dimming. This has become of particular concern since those who experienced the Second World War and the Holocaust are increasingly fewer in number. Seen from today’s perspective, the film can be posited as counter to the contemporary nostalgia for ruins in what has more recently become known as “ruin porn”.[3] In the plethora of films, photographs and other cultural examples that aestheticise the past, images of traumatic historical events, the detritus of industrial modernity, ecological disasters and war are made mesmerising, awe-inspiring and pleasurable to consume. Typically, such images remove contradictions from the landscape of ruin, a beautiful image hides the social disharmony and smoothes over the destruction that comes hand in hand with the ruin.[4] The (now absent) past is seen with sentimentality as a time of productivity and wellbeing. In our historical moment, when images and history are being elided, the fragmentation and ambiguity of Brutality in Stone’s modernist aesthetic can provoke a reflection on the present moment of its reception. Similar to the way that the aesthetic of Brutality in Stone sought to critique the motivations of the fascist aesthetic, in this article, I argue that, seen today, the film’s stylistic strategies reinstate the historical power of architectural ruins. What might be called the authentic power of the ruin discovered by the film counters the absolute iconic authority with which Hitler imbued ruins in general. The film’s experimentation thus also functions as a doorway to a more complex understanding of the contemporaneous, the present moment of its reception.

In the immediate postwar years, all visible vestiges of Germany’s Nazi regime were systematically removed from public display: the swastikas that remained after Allied firestorms were smashed, and the statues and monuments were destroyed. The ban on public display of Nazi symbols became law shortly after the war’s end. Nevertheless, many of the buildings designed and built by the Third Reich were left standing. In line with Germany’s current commitment to educating about, rather than ignoring the past, the complex histories of such buildings are interrogated by documents and panels at given sites. In the case of the Nuremberg complex, a documentation centre for visitors has been integrated into the north wing of the former Congress Hall and text panels placed at entrances. Seen from our contemporary perspective, Brutality in Stone speaks to this tendency to consciously encourage civic engagement of the site, not idolisation of the past. Indeed, the film encourages spectator-negotiation of Germany’s traumatic past (Young). The film achieves this through critiquing the relationship between camera and architecture that was established by the Nazi propaganda machinery in the interests of mystifying and aggrandising the sites of Nazi power. In the most well-known example of this type of cinematic representation of architecture—Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will (Triumph des Willens,1935)—the structures of the Nuremberg rally grounds, as well as buildings in the city centre draped in swastika banners, are shot through wide-angles and long shots to convey the immensity of the buildings, monuments and symbols. When they are accompanied by low-angle shots of speakers at the podium, looking up to the sky from the base of flag poles, and through a moving camera that follows a Mercedes motorcade through the city streets, architecture and camera come together to emphasise the power and heroism of Hitler and the Reich. By comparison, Brutality in Stone offers a counter-monumentalisation of the architecture as site of ideological spectacle.[5] In doing so, the film creates a cognitive and associative site of memory, rather than an ossification of the ruins and their complex historical significance. As I demonstrate, Brutality in Stone presents the architecture as a conglomeration of fragmented ruined surfaces, rather than as an oneiric symbol of an authoritarian regime.

Figure 1: Camera ascending staircase in Brutality in Stone (Brutalität in Stein),

by Alexander Kluge and Peter Schamoni. Alexander Kluge Filmproduktion, 1961. Screenshot.

In what might be understood as an ironic challenge to the power and longevity of Hitler’s anticipation for the Third Reich, the film uses the ruin as the site of its counter-monumentalisation. Albert Speer’s “Theory of Ruin Value” (Die Ruinenwerttheorie) was introduced as official policy by Hitler following his encounter with the ruins of ancient Rome as Mussolini’s guest in 1938. After that visit, Hitler ruled that the Thousand Year Reich must use building materials which would anticipate the eventual ruin of its buildings. In turn, these ruins would resemble those in Ancient Greece and Rome, providing a lasting symbol of the greatness of the Reich (Spotts). Brutality in Stone shows the ruins to be the very opposite: crumbling, ephemeral and historically mutable in their significance.

Together with the complex image-sound relations and the blurring of static and moving images, as well as archival and original footage, the camera’s relationship to the architecture refuses to attribute power to the building remnants from the darkest period of German history. In this way, the film leads to a critical vision that contributes to the creation and ongoing awareness of what Michael Rothberg has termed “multidirectional pasts”.[6] In 1960, Kluge and Schamoni were concerned to engage critically with a past that had, until then, been largely uninterrogated through cinema in the Federal Republic of Germany.[7] Similarly, in 1990, Rentschler contributed to a body of work that emphasised the making of new memories of a past that had changed overnight thanks to the fall of Communism. In turn, today, we can look at the film as a kind of “anti-architecture” documentary designed to maintain consciousness of the processes of present history as they are created by memories of the past and their representations.

Cinema and Ruins

Figure 2: Fragmented architectural buildings. Brutality in Stone. Screenshot.For Brutality in Stone there are no human survivors in the ruins of the Nuremberg complex. Rather, the film witnesses abandoned structures, empty of human life, through a restless camera searching for memories of the past as they ricochet around and resonate across the remains of the Congress Hall and the parade grandstand on the Zeppelin Field. The film combines still and moving images of the site in all stages of dilapidation. We see it from low angles, through canted and closed frames, always against cloudless white skies. On the soundtrack, we hear speeches by Adolf Hitler and by Alfred Rosenberg. Crowds cheer, party rally speeches ring out, and a clipped expressionless voice reads fragments of Rudolf Höss’s diary in voiceover. People do not appear in the rally grounds as they are presented by the film. Rather, from the critical standpoint of 1960, the camera discovers the past in the architectural structures, and then re-enacts it through the addition of the voiceover, found sound and music. This present is created through a relationship between abandoned ruins of Nazi neoclassical architecture and the medium of cinema. Most importantly, the architectural ruins of the past are rediscovered from multiple perspectives to expose them as the site where fantasies were manufactured and multiple crimes conceived.[8]

In contradistinction to the impetus of a film such as Riefenstahl’s that uses lighting, sound effects and camerawork to communicate the spectacle and drama of the future German Reich that will be played out on the architectural stage of Nuremberg, Brutality in Stone denies its audience the potential thrill of engaging with the energy secreted at the site. It removes the mystery and awe that might otherwise be generated in the translation from object to screen. In her work on André Bazin’s writing, Angela Dalle Vacche elucidates the psychological mystery and escape generated by the immediate postwar art documentary. According to Dalle Vacche, for Bazin the art documentaries work to create an identification between viewer and painter through the camera’s translation of painting into film (292). It is this relationship that is truncated or interrupted in Brutality in Stone—between the film’s viewer and the Nazi architect. Brutality in Stone represents the Nuremberg grounds as a “shattered” ruinous site, thereby refusing all possibility of identification with the intention of its creators. Like the medium of cinema, the architectural ruin is shown to be in perpetual transformation. The film shows not a static object that preserves, leading to absolution of the past, but a living phenomenon that provokes negotiation of the turbulent history of the past in the present. These present memories are, in turn, the groundwork for a future free of such violence.[9]

Brutality in Stone focuses on majestic halls (found and imagined), overgrown paths, crumbling steps, underground caverns and broken walls. In the first half of the film, the camera moves through and around the architectural spaces, inviting us to identify them as the place where a history began thirty years earlier. They are seen from the point of view of a present (1960) that has literally let the grass grow and, by extension, started to ignore the past. The film then takes us into decaying corridors at the Nuremberg grounds inviting us to witness, not to revere or be inspired to create one-dimensional memories. In keeping with the film’s impetus to fragment, shatter and challenge the past that took place at this site, so the memories it invites us to create are multiperspectival.

Figure 3: Dilapidated steps in Brutality in Stone. Screenshot.

As Kluge himself has said in relationship to the realities represented in his films, the films are “constructed” to offer multiple histories, narratives and possibilities of interpretation. Never one to impose an interpretation on a spectator, always preferring to create a provocation to “the film in the viewer’s head”, Kluge’s experimental process is designed to evoke, to use critic Peter Lutze’s term, an “imaginative” response.[10] In turn, if the film in the spectator’s head is determined, as Kluge has repeatedly claimed, “from the perspective of today”, the film’s meaning is located in its experience. The film in the spectator’s mind, created through Kluge’s particular montage process, becomes the real (as in authentic) history represented. As Lutze describes it in relation to The Power of Emotion (Die Macht der Gefühle, 1983), the montage process is complex and varied, thus enabling unique and multiple possibilities for historically inflected interpretations from different spectators (115–21).

In Brutality in Stone,we are invited to witness the plurality of histories spawned at this site, in our present moment. Thus, the cinema engages with the crumbling walls to create warnings for the present and future. The textual epigraph to Brutality in Stone claims that the architectural remnants testify to the memory of the National Socialist era.[11] Through fragmented cinematic representations of ageing architecture, the abandoned buildings bear witness to the devastation, and keep it alive for every viewer in their historical present. The buildings have stood through multiple histories, beginning with that of the fantasy of an all-consuming Nazi power and perversion. As I demonstrate below, the film encourages us to consider the grounds within their subsequent history of Allied destruction, postwar neglect, and post-1989 repurposing.

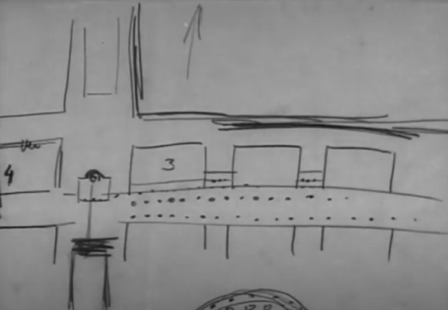

Figure 4 (above): Archival image of Hitler sketching.

Figure 5 (below): Archival image of a sketch by Hitler. Brutality in Stone. Screenshots.

The film delivers this reminder to today’s viewer through two distinct strategies that are often associated with modernist cinema’s critique of history and its representation.[12] First, Brutality in Stone mobilises the capacity of the film camera and the abandoned architectural ruin to traverse and reorganise historical times and spatial locations. The film cuts between the past, present and future: archival images of Hitler examining architectural plans and his own sketches from the past are re-presented. Similarly, the Nuremberg grounds in the film’s present of 1960 are edited together with other material such as archival photographs of Speer’s architectural plans and models for Germania, the projected renewal of Berlin, the future German capital that was never built. In their mélange, without distinction between past, present and future, archival and present-day (1960) images, the ruins and their representation not only traverse time, but true to the capacity of both, they also reverse and manipulate time (von Moltke). Second, the film fragments the image and, thus, potentially disorients the viewer. Both of these strategies result in a reorganisation of time and space, that is shared by the abandoned architectural ruin as it has been theorised.

Figure 6: Archival sketch of the future German Reich. Brutality in Stone. Screenshot.

Georg Simmel has argued that the ruin as a fragmentary representation of the past offers a contradictory phenomenon evoking multiple perspectives: evidence of the truncated future of a ruined past, natural transformations of man’s cultural constructions and visions, and hopeful emblems covered in the patina of age and simultaneous signs of decay and destruction. (Simmel). The ruin and the cinematic image are twin phenomena enabling a confusion of “multi-directional pasts” in Brutality in Stone. Through editing, camerawork, sound-image relations, a lack of distinction between archival and newly shot footage, films and photographs, representation and reality, past and present are woven together to confound and provoke the spectator. Lastly, thanks to the cinema’s ability to abstract places and spaces, the historical relevance of Brutality in Stone extends beyond the specificity of wartime German history and its cinematic representation. The film’s signifiers are ultimately set loose and, as I argue, we are asked to rethink the past in our present moment, thus recognise our assumptions and misconstructions (Lyons).

Fragmented Times and Spaces

In his call to counter the nostalgia that infests contemporary discourse on ruin culture, Andreas Huyssen argued in 2006 that, over the previous fifteen years, there had been a “strange obsession” with ruins as part of the larger discourse on memory, trauma, genocide, and war. He writes: “The architectural ruin is an example of the indissoluble combination of spatial and temporal desires that trigger nostalgia. In the body of the ruin, the past is both present in its residues and yet no longer accessible, making the ruin an especially powerful trigger for nostalgia” (“Nostalgia” 7). Within the first few minutes of Brutality in Stone, following a series of tight, static shot, close-ups of walls, cornices and steps, a crescendo of drumbeats is interrupted by a voiceover telling us we are at the Nuremberg Rally grounds. The camera then moves fluidly, climbing steps that are progressively stained and cracked, with weeds growing in their crevices. The image is accompanied by a swell of music that we are told is an orchestra preparing to play the fourth movement of Brahms’s Symphony No. 1 in C Minor. This is followed by Rosenberg’s closing words at the same party rally. The soundtrack incites us to anticipate that a momentous event will be discovered when the camera reaches the top of the stairs. Simultaneously, thanks to our privileged historical perspective, we know that a disaster is on the horizon. Following several repetitions of Sieg Heil from a crowd on the soundtrack, silence pervades, and the camera slowly approaches the closed doors of the Zeppelin façade. A dissolve transports us into a hallway, accompanied by a voiceover reading excerpts from Höss’s diaries, fastidiously describing the preparations for people to be transported to Auschwitz. The visuals confuse: where are we inside the architectural complex? Despite the camera’s fluid movement forward through colonnaded space, the image lacks orientation and is interspersed with repeated tight closeups of unremarkable stone facades, dissolves to different spaces and an eventual descent into a pitch-black tunnel before a cut to unidentified sections of the complex. The familiar fulcrum of the grandstand with the “Führer’s Rostrum” at the centre of the complex is not shown. Neither is there an establishing shot of the space. The camera proceeds to pan, more haltingly than before, across sections of bricks walls and, finally, halfway through the short film, a full shot of the unfinished Congress Hall with a slither of whited-out sky above. As the voiceover begins reciting the history of the unfinished construction of the Congress Hall, our thoughts are likely to be haunted by the people referred to in Höss’s earlier speech.

Figure 7: Unfinished Congress Hall. Brutality in Stone. Screenshot.

The editing together of fragmentary images of the architectural complex and varied sound snippets not only creates confusion. As we remember the people transported to their deaths, the visual agitation of the camera starts to incite our own growing discomfort. The tension between images of the monumental neoclassical hallway empty of people, fragments of the dilapidated arena, sounds of screaming voices, speeches, silences and matter-of-fact historical details bring alive scenes of journeys to the gas chamber described by Höss. The strategy of overlaying sound from an earlier sequence to create a spectre of the past in the present is commonly used by experimental documentary. Often, as critics acknowledge, the production of nonlinear fragments at the level of sound and image are designed to haunt the film narrative and, by extension, the viewer’s encounter with the events depicted (Lippit). In turn, the distinction between illusion or imagination and reality is lost. In Brutality in Stone this conflict between sound and image, past and present, points to the blurring of fantasy (aesthetic representation) and the reality of Nazism. These sequences take on a powerful resonance when we recognise that it is not just that walls of the Nuremberg complex resound with atrocities that occurred elsewhere, but that Höss’s discourse, the narrator’s historical facts, Hitler’s speeches and great orchestral music are the different and conflicting histories witnessed by the stone walls at Nuremberg.

These sequences capture Kluge’s much written about desire to engage his viewer in the film experience, such that they will become a historian as opposed to an observer of history. As Eike Friedrich Wenzel claims, for Kluge, history is grasped through the “filmic process of work on our perceptions […] an incessant questioning of the images we make of history” (174). Wenzel goes on to claim that, for Kluge, “historicity is both the irreducible horizon of his work and a social utopia. All his films are informed by an insistence on the significance of historicity, an insistence that viewers are invited to adopt as an attitude—towards themselves, towards the film, and towards their own social reality” (175). Following Wenzel’s logic, therefore, history in Kluge’s film is not a static objective phenomenon. Rather, history lies in the viewer’s experience and subsequent understanding of its representation. Similarly, as Kluge himself says, history cannot be interpreted through revelation of the mind or the character behind the structures and remnants of the past (Wenzel 198). As Kluge’s work on the viewer as producer within the public sphere insists, the disjunctions and abrupt shifts, ostensibly connected or bridged in film through sound, are designed to create discomfort for the viewer, forcing them to find coherence and meaning elsewhere. What matters is the audience’s interaction with the film as a channel for producing historical communication (Kluge, “On” 44). Like Leni Peickert, the protagonist of Kluge’s Artists Under the Big Top, Perplexed (Die Artisten in der Zirkuskuppel: Ratlos, 1968), the viewer of Brutality in Stone is called upon to be the historian of her own historical moment. Moreover, that historical present is only sayable and visible through its relationship to other historical moments. In the conflicting spaces between sound and image, the ongoing multivalence of history and different historical moments haunt the spectator’s experience of the film and history. We are disoriented within the visual representation of the architectural ruins and, simultaneously, transported through cinema to the location where we hear speeches and sound effects that remind us of the horrendous Nazi past. The past is heard in the voice of the perpetrators, the violence thus being made visible to our minds as we imagine the crimes piling up one on top of the other. As we listen to the commandant of Auschwitz on the soundtrack, our thoughts are propelled into what is looming for Germany in the 1940s, following the historical speeches. Our thoughts are met by the “storm” on its way, followed by the “pile of debris” in the ensuing scenes (Benjamin 257–8). Thus, in the present of the film’s making—so we assume at this point in its unfolding—the Nazi Party’s use of the stadium in the late 1930s as well as the crimes announced there, then and thereafter, are introduced. Memories of the devastation unfold in our minds. There is no nostalgia in these shots of (now) past historical moments. Through our engagement with the film’s representation, the Nuremberg stadium is given an afterlife. Brutality in Stone, and its ongoing reception, demonumentalises, dematerialises the meaning of the site as a platform for memory. The film, and our memories, from different times and spaces, effectively extend the site beyond its material manifestation to a platform for future commemoration. Ultimately, the film takes the site out of the hands of Nazism (Cherry 7–8).

What of the future of Kluge and Schamoni’s film, the present of our own watching in the twenty-first century? Since the Allied Victory in 1945, the question of what to do with the Nazi Party Rally Grounds has continued to play out in multiple private, civic, and media forums. Indeed, the struggle to find an appropriate and ethical way to remember the Nazi past continues in Germany today.[13] As a result, the site has gone through periods of being debated, neglected, and partially destroyed. In 2001, a documentation centre with a permanent exhibition on the history of the grounds was opened in the Congress Hall. The future of the structures, including the Zeppelin Field—so often represented as the site for the birth of the historical ideology designed to end history—continues to be the subject of ongoing public debate (Macdonald). In the meantime, the same already damaged stone walls in Brutality in Stone continue to crumble. Today, they are defaced with mould, graffiti, bird droppings, and the stadium is in use for various large-scale public events and football games. In 2017, local authorities proposed a renovation of the Zeppelin Field, estimated at €73 million, to be financed by taxpayers (Zelnhefer). The proposal raised conflicting opinions: locals protested the expense in an age of austerity, others argued that the structures had to be renovated, enabling reflection on the dark Nazi past, and still others questioned the building of a static monument through renovation of the complex (Paterson). At the same time, city officials expressed concern for the dangers posed to passers-by and visitors by the crumbling and decaying structures. Specifically, they were worried about debris falling onto the sidewalk.

From a different perspective, to leave the buildings in their partly destroyed, unfinished, and now further deteriorating state, is equally susceptible to the accusation of monumentalisation. As Huyssen argues, the monument in ruins not only aids memory and healing, but it can also act as a screen for insight into the complexities of history by privileging the ruin as authentic object from a fixed moment in the past (“Present Pasts” 14). And because the terror and destruction of the Nazi past is today far removed from the lives of many, acknowledgment of its extent and ramifications is threatened, particularly by young locals who play football on the Zeppelin Field or tourists who skip the museum and head straight to the rostrum where Hitler delivered his speeches. In addition to those histories secreted in the ruinous cracks and repeated in the mind of the viewer thanks to the spaces between sound and images in Kluge and Schamoni’s film, today, the histories conceived by visitors are multiple and contested. Some are astounded that the Documentation Centre exhibition does not do more to critique the narrative of the past (Macdonald 141–2). Others are dangerously ignorant of the significance of the complex (142). Still others experience the site and its associated German history through presentation by tour guides—often history students from the local university—and educators.

Huyssen’s explanation of the labyrinthine incompletion of Piranesi’s Carceri d’invenzione—etchings of fictional prisons begun in 1747—offers a valuable aesthetic framework for understanding the spatial and temporal fragmentation that we find in Kluge and Schamoni’s film of the Nuremberg complex. Huyssen writes,

[Piranesi] privileged arches and bridges, ladders and staircases, anterooms and passageways. While massive and static in their encasings, the prisons do suggest motion and transition, a back and forth, up and down that disturbs and unmoors the gaze of the spectator. Instead of viewing limited spaces from a fixed-observer perspective and from a safe distance, the spectator is drawn into a proliferating labyrinth of staircases, bridges, and passageways that seem to lead into infinite depths left, right, and center. It is as if the spectator's gaze is imprisoned by the represented space, lured in and captured because no firm point of view can be had as the eye wanders around in this labyrinth. (“Present Pasts” 23)

Huyssen goes on to argue that representations such as Piranesi’s Carceri etchings can be understood as spatialisations of history in which space is made temporal through visual representation. If Brutality in Stone is seen through the same lens, the camera ensures that we are denied the potentially comfortable position of viewing the spaces and constructions as historically distanced, belonging to a fixed point in the past. Rather, the halls and stairs as platforms for great speeches about a future taking place in another time and space are filmed in the present of the 1960s. They are then edited together with re-presented images of documents, models and plans for an incomplete project from the past. Thus, past plans for the complex’s future, the destruction and dilapidation of the buildings as ruins in 1960 are woven together into the single temporality of the short film.

Following the camera’s increasingly uncertain journey through the ruins in the first half of the film, Brutality in Stone cuts to still archival images of sketches made by Hitler, models and architectural plans of Germania. While the camera continues to glide through images of Speer’s models, bombs exploding can be heard on the soundtrack. Memories of actual destruction further overlay imagined future constructions when the narrator relates Hitler’s order in August 1943 to create one million basic dwellings to house bombed-out citizens. These snippets of speeches, radio announcements and cheering crowds are interspersed with silence, sirens and a few bars of composer Hans Posegga’s chromatic music. Thus, in these passages, photographs, sketches and models turn into moving images over time. In addition, the merging of Brutality in Stone and archival images and sounds further blurs past and present. These different temporal perspectives and registers are not signalled by the film as distinct, but rather, are freely edited together, reminding us that history is always a conglomeration of past and present, illusion and reality. In turn, archival images and sounds of the past describe the then-present architectural structure, which in itself is unfinished and a fantasy. As Lutze explains, for Kluge, the viewer’s role is not to identify the source of the sounds and images, but to discern connections and common features, to make sense of potential incoherence(125–31). Thus, the film draws our attention to histories in which monumental, heroic architectural spectacles designed to persuade the masses emotionally of an ideology will lead to a collective nightmare. This exposure of the multiple truths of history resists the spectacle, and thereby, refuses a heightened emotional enthusiasm. Instead, if we are to follow Kluge’s oft-espoused thinking, the viewer is led to respond to her perceptual awareness and the critically transformative potential behind the smokescreens of ideology.[14]

Figure 8: Models for the Future Germania. Brutality in Stone. Screenshot.

If the labyrinthine temporal logic of the images in Brutality in Stone is any indication of the place of the represented past in our present, then history is not over and we do not have a privileged position from which to survey it. Rather, while watching Brutality in Stone, we are jolted by the shifts in perspective and surrounded by the fragments. The end result is that the crimes spoken of in the voiceover are not only in the past we know to have been realised (in the concentration camps) and not realised (the Thousand Year Reich), but continue to weigh on our experience in the present.As Huyssen reminds us, the dimension that is always present in the ruin is the “consciousness of the transitoriness of all greatness and power, the warning of imperial hubris, and the remembrance of nature in all culture” (“Authentic Ruins” 21). In other words, contrary to the will of the powerful, and the apparent solidity of stone, nothing lasts. The man-made ruins of the past will always be overwhelmed by the magnitude of nature. However, the incomplete buildings also anticipate a future in which they will become whole. As long as these particular ruins remain unfinished, there will always be a future—if only in the imagination—that will apparently complete them. The ruins are haunted by death, and yet, the cinema has the capacity to release them from temporal stasis and incite its audiences to imagine their revivification. Accordingly, the cinema’s disrespect for the linearity of history brings this past embodied in what Huyssen calls “ruined and memory-laden architecture” into our present to remind the contemporary viewer of its continued existence (“Authentic Ruins” 26).

Cinema has the capacity to create shifting visions of place and space as well as history. The camera of Brutality in Stone sets the location of the Nazi Rally grounds into motion, making them spatially obscure, multilayered, able to be seen from new perspectives without the hierarchy of power and ideological persuasion that were once delivered from the podium. The film races across brick, stone, cement surfaces, as if running historical times as well as spaces together, indicating the struggle between them. However, the cinema is not alone here: architectural ruins also confound the organisation of space and history, particularly given what the site would have been had it not been bombed by the Allies in early 1945. The ruin creates a dynamic place, a fragmented architecture in decay, characterised by a tension between past, present, and future. This breaking apart of the ruined walls thanks to the uncertainty of spatial relations between them is underlined by their cinematic presentation. The fragmentation is transposed and underlined in the space between still and moving images in Brutality in Stone. By using the camera and editing capacities to fragment the space of the architecture, as well as fuse incompatible histories, Kluge and Schamoni refuse the material and visual power of architecture as ideology.

In addition, the fragmentation of the image together with the absence of an expositional image to orient the viewer within the rally grounds results in a flattening and ultimate abstraction of the buildings. The reduction of the historical structures to two dimensional architectural plans and cinematic images is a further use of the cinema to refute the power of the creator, the mind and spirit of those who designed and built the rally grounds.[15] Hitler believed in the ruin as oneiric, as having the potential to bring rebirth of his power in the future (Stern). Brutality in Stone does the very opposite. The relationship between camera and architecture presents a fragmented, “multidirectional” future, that is, in contradistinction to that imagined by the Reich and its speeches at the site.

In another visual tension, architecture and photography are put into a dialogue that is simultaneously conflictual in Brutality in Stone. Thanks to the stasis and two-dimensional flatness of the images, we are often unsure if what we see is the buildings themselves or a photograph of the same. Similarly, in the middle section of the film when we see Speer’s life-like architectural models, in keeping with his intention, we could be deceived into thinking we are looking at a building itself. These fragments reflect back on the tension between photograph and film, encouraging us to ask: what is the status of this image, and what does it document? Is the camera looking at a representation or the thing itself? The film edits together archival photographs and films, images of buildings, plans and projections, into a series of histories in which the unspoken secrets of places that may or may not exist are confusing and illogical. In the end, we are left with our deception. Thus, unlike the audience at the party rallies held in the Zeppelin Field in the late 1930s, viewers of Brutality in Stone are encouraged to reject the presentation of an illusion (or fantasy) as the reality. Through the obfuscation of the distinction between still and moving images, archival and original footage, we doubt the credibility of the architectural designs. Architecture, models of buildings that will never be built, photographs, and drawings all coincide on the surface of the film image. The uncertain status of what we are seeing, in turn, pushes us to attend to the deception of the multiple discourses of history coinciding, at times, unpredictably.Abstracting History

Lúcia Nagib argues in her discussion of Brutality in Stone that the concrete walls and floors, steps, halls, tunnels and stony terrain of the rally grounds are used to “convey abstract concepts” (84). She claims that this abstraction enables the film to reach beyond the specific history of the ruins at Nuremberg. Moreover, we can extend Nagib’s argument to the present historical moment. Today, Brutality in Stone’sconfrontation through fragmented ruins exposes the illusions and rhetorical myths that make up the abstract, but nevertheless, real notions of power, injustice and violence that proliferate and resonate in the present. Brutality in Stone nurtures the creative relationship between film and architecture (in ruins) to make visible the crimes of a historical and geographical past. As I demonstrate above, the film doesn’t depict the crimes of the Nazi Holocaust in its past. Rather, it evokes this past through its resonance within its historical present of Germany in the 1960s (Rentschler). Moreover, this resonance extends into our present, two decades into the twenty-first century.

There are still further levels of abstraction beyond the film’s specific focus on Germany in the late 1930s and 40s, specifically those events referenced in the soundtrack and evoked in the viewer’s memory. Consistent with Nagib’s claim for the abstraction of Kluge’s images and the building therein, Wenzel points out that Brutality in Stone attempts no analysis of the architecture. True to Kluge’s later filmmaking practice, the film is conscious to the point of a hermeneutic impetus to reveal its own interaction with the architecture of the past (Wenzel 182). That is, the film is not about the architecture, its form or structure, per se, but about the historical truths and lies within its ruins as we see them “today”. The grass has begun to grow over the corners, steps, hallways of the Nuremberg complex as it is represented by Brutality in Stone, such that the immediate layer of history has been consumed by nature, literally. Further, on a metaphorical level, the moss and dirt communicate that it is not the politics of the buildings, or what took place therein, but the past they evoke, the stories secreted within the stones, that must take priority today. In addition, as Wenzel also points out, Brutality in Stone never makes clear the exact contours of the relationship between the past and the present. This refusal underlines the abstraction that, in turn, opens up to multiple interpretations beyond the film’s specific times and places.

What message then is delivered through the abstraction that results from the relationship between film camera and architecture in ruins? If the film’s reluctance to analyse the architecture enables a shift towards the buildings’ historical significance, what does it find? The ruins of history and the fantasy of power are lurking at this site as it is represented in Brutality in Stone. In their filmic re-presentations, the corridors and spaces, walls, and objects stumbled upon as the film wanders and pieces them together are further abstracted to the extent that we can both see and not see what we are watching: as noted above, the film’s refusal to offer an establishing shot of the complex in its entirety makes it difficult to orient ourselves within the architectural space. Instead, it shows fractured, conflicting perspectives through a camera that never rests in one location. It is not only the linearity and logic of historical narrative that is fractured by the film, but also, the rules of tectonics and perspective, leaving us lost both in space and time. We never know where we are inside the grounds, and we never fully conceive of the relation of the parts to the whole. Neither are the spaces of inside and outside, above and below ground, clearly differentiated. This becomes further confused by the lack of clear distinction between the use of archival and newly shot images. Thus, the film refuses to offer a stable perspective within space, as well as within history, and within Nazi Germany.

Inside these ruins made to appear labyrinthine and fragmented, the spaces are experienced as confusing. The viewer is confronted by the breaking apart of history such that our own becomes implicated within these walls. We do not sit outside history when looking at beautiful images memorialising the past. Invoking Benjamin’s conception of our surrounding history as he articulated it in the often-quoted “Theses on the Philosophy of History”, the storm is now truly blowing so vigorously and violently, and we are caught in the wreckage whether we like it or not. This confrontation with our own implication in the historical breakdown represented by Brutality in Stone is a modernist strategy that places critical analysis as the responsibility of the spectator. It is, ultimately, the success of Kluge’s film to continue enabling an immersion in the processes of history in the twenty-first century. Moreover, this can be identified as the film’s gesture beyond the specific history of the Nuremberg grounds: by asking the spectator to take responsibility for the continued interpretation and understanding of history, the film points to a broader historical intention. History, as Benjamin would have it, is not something on which we should turn our backs. Rather, the storms of the past must be recognised for the wreckage they have left in the present and future.

In Brutality in Stone,film and architecture, as well as the idea and materiality of the built environment, come together not just to expose, but also to invent, as well as to connect varied histories, the relationship between which must be remembered within public discourse. The documentary moving image brings together multiple memories and histories, secreted in places and spaces that may have been built in the past for an invented future, but have become the challenge of the present moment. Kluge and Schamoni do more than use the medium for the simultaneous creation and representation of invisible histories in decaying architectural structures. They let the viewer loose inside the space of the film, and by turns, inside the space of the Nuremberg complex, leaving her with no option but to be reminded of the power, manipulation and destruction that led to this ruinous landscape. As one traumatic past bleeds into the next and both, in turn, extend into the present, it is imperative that we remember these potentially distant histories. While they once overwhelmed our consciousness, we must not let them disappear. This complex of histories and places and spaces in motion depends on the film camera coming together with architecture for the ongoing longevity, multiplicity, and spatial reverberations of history.

The history in which power destroyed and the Nazis attempted to rewrite the future with their architecture as the icon and facilitator of that future is discredited by Brutality in Stone. It is deconstructed through the use of an interaction between ruins (the unfinished and abandoned spaces of the Nuremberg complex) and the camera with its ability to further fragment and disorient. We are confused because we are not given a fixed position or singular historical moment from which to see the past or the rally grounds. In addition, the tensions between sound and image, and the ongoing uncertain status of the image, both of and in the film, confuse our understanding of the place, its history, as well as the histories it represents. Even though the film was made sixty years ago, it speaks to the contemporaneity of the ongoing imperative to see and understand history differently. Such is the capacity of the cinema and the architectural ruin to reorganise the unfolding of time, the representation of history and, and therefore, our collective memories.

Notes

[1] Simultaneously, the public discourse through which historians vigorously and controversially debated the place of the Nazi past (the Historikerstreit) in contemporary Germany had already begun. For the ongoing relevance of the Historikerstreit in reunified Germany, see Rutschmann. I take this notion of making visible and sayable from Jacques Rancière’s writings on the politics of the image.

[2] Kluge insists that historical analysis is responsible for the making conscious of the past in the present in the struggle against the repression of the past. This is most articulately laid out in his work with Oskar Negt, History and Obstinacy.

[3] The term “ruin porn” is used to critique nostalgic tendencies that romanticise the past through representation of the ruined (modern) past in a post-modern, post-industrial moment (Lyons).

[4] For a sophisticated account of the phenomenon of ruins made spectacular, see Orvell.

[5] The notion of the counter-monument was first explored in English language literature by James Young and his analysis of the monuments that resist or efface traditional monuments as markers of official history. For a discussion of the historical spectacle often created by Nazi architecture, see Hagen and Ostergren. I here argue that a film such as Brutality in Stone deliberately counters the historical intention of the architecture.

[6] The notion of multidirectional pasts is taken from Michael Rothberg’s writings on the importance of multiple approaches to, and thus interpretations of, the varied and often conflicting pasts signified in Holocaust memorials.

[7] Postwar films made in the German Democratic Republic did represent the memory of the National Socialist past, if not always directly (Allan and Sandford).

[8] While Nuremberg is not commonly associated with the Nazi planning of the Holocaust, we will remember that the Nuremberg Laws were written there, and that the site was used for military strategy as well as rallies and propaganda exercises.

[9] In the literature on counter-monument as key to the future of Germany’s coming to terms with the past, the static monument is thought to ossify the past while the transitory, specifically, ephemeral, provokes interrogation and education of the past (Young).

[10] Kluge himself often uses the term “the film in the viewer’s head” in his writing (Gregor 157–8; Kluge, “Pact” 236).

[11] “Die verlassenen Bauten der nationalsozialistischen Partei lassen als steinerne Zeugen die Erinnerung an jene Epoche lebendig warden.”

[12] These discussions have primarily focused on European art and auteur cinema by directors such as Alain Resnais, Michelangelo Antonioni, Federico Fellini, Jean-Luc Godard (Kovács).

[13] For a particularly concise summary of the debates, see Niven.

[14] This power to determine reality from fantasy that begins with the formation of perception was fundamental to Kluge’s groundbreaking analysis of the mechanisms of the public sphere in postwar Germany. Of particular relevance here is the role of television as a public sphere. It is a notion that resonates through all his historical films as well as his documentaries (Negt and Kluge 96–148).

[15] As critics of the art documentary from André Bazin onwards agree, the genre characteristically looks to find the person behind the creation. Indeed, this is true of other works on Nazi architectural plans. A documentary such as Peter Cohen’s Architecture of Doom (1989) is committed to representing the architecture as a way to discovering the mind of the man who conceived Nazi ideology.

References

1. Allan, Sean, and John Sandford, editors. DEFA: East German Cinema, 1946–1992. Berghahn Books, 1999.

2. Architecture of Doom [Undergångens arkitektur]. Directed by Peter Cohen, Poj Filmproduktion A; Stiftelsen Svenska Filminstitutet; Sveriges Television AB; Sandrew Film & Teater AB,1989.

3. Artists Under the Big Top, Perplexed [Die Artisten in der Zirkuskuppel: Ratlos]. Directed by Alexander Kluge, Kairos-Film, 1968.

4. Bazin, André. “Painting and Cinema.” What Is Cinema? Vol. 1, edited and translated by Hugh Gray, U of California P, 2004, pp. 164–72.

5. Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, Fontana/Collins, 1973, pp. 255–66.

6. Boym, Svetlana. “Ruinophilia: Appreciation of Ruins.” Atlas of Transformation, 2011, monumenttotransformation.org/atlas-of-transformation/html/r/ruinophilia/ruinophilia-appreciation-of-ruins-svetlana-boym.html. Accessed 12 Sept. 2020.

7. Brutality in Stone [Brutalität in Stein]. Directed by Alexander Kluge and Peter Schamoni, Alexander Kluge Filmproduktion, 1961.

8. Cherry, Deborah, editor. “The Afterlives of Monuments.” The Afterlives of Monuments, edited by Deborah Cherry, Routledge, 2014, pp. 1–14.

9. Dalle Vacche, Angela. “The Art Documentary in the Postwar Period.” Aniki: Portuguese Journal of the Moving Image, vol. 1, no. 2, 2014, pp. 292–313, DOI: https://doi.org/10.14591/aniki.v1n2.90.

10. Gregor, Ulrich. “Interview with Alexander Kluge.” Herzog/Kluge/Straub, edited by Peter W. Jansen and Wolfram Schütte, Carl Hansen Verlag, 1976, pp. 153–78.

11. Hagen, Joshua, and Robert Ostergren. “Spectacle, Architecture and Place at the Nuremberg Party Rallies: Projecting a Nazi Vision of Past, Present and Future.” Cultural Geographies, vol. 13, no. 2, Apr. 2006, pp. 157–81, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1191/1474474006eu355oa.

12. Hell, Julia, and Andreas Schönle. Introduction. Ruins of Modernity, edited by Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle, Duke UP, 2010, pp. 1–14.

13. Huyssen, Andreas. “Authentic Ruins: Products of Modernity.” Ruins of Modernity, edited by Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle, Duke UP, 2010, pp. 17–28.

14. ---. “Nostalgia for Ruins.” Grey Room, no. 23, Spring 2006, pp. 6–21, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1162/grey.2006.1.23.6.

15. ---. “Present Pasts: Media, Politics, Amnesia.” Public Culture, vol. 12, no. 1, 2000, pp. 21–38, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-12-1-21.

16. Kluge, Alexander. “The Assault of the Present on the Rest of Time.” New German Critique, no. 49, Special Issue on Alexander Kluge, Winter 1990, pp. 11–22, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/488371.

17. Kluge, Alexander. “On Film and the Public Sphere, 1981.” Alexander Kluge: Raw Materials for the Imagination,edited by Tara Forrest, Amsterdam UP, 2012, pp. 33–49.

18. Kluge, Alexander. “Pact with a Dead Man.” West German Filmmakers on Film: Visions and Voices, edited by Eric Rentschler, Holmes and Meier, 1989, pp. 234–41.

19. Kluge, Alexander, and Klaus Eder. “Debate on the Documentary Film: Conversation with Klaus Eder, 1980.” Alexander Kluge: Raw Materials for the Imagination,edited by Tara Forrest, Amsterdam UP, 2012, pp. 197–208.

20. Kluge, Alexander, and Oskar Negt. History and Obstinacy. 1981. Edited by Devin Fore, translated by Richard Langston, Zone Books, 2014.

21. Kovács, András Bálint. Screening Modernism: European Art Cinema 1950–1980. U Chicago P, 2007.

22. Lippit, Akira Mizuta. Ex-Cinema: From a Theory of Experimental Film and Video. U of California P, 2012.

23. Lutze, Peter. Alexander Kluge: The Last Modernist.Wayne State UP, 1998.

24. Lyons, Siobhan, editor. Ruin Porn and the Obsession with Decay. Palgrave, 2018.

25. Macdonald, Sharon. Difficult Heritage: Negotiating the Nazi Past in Nuremberg and Beyond.Routledge, 2009.

26. Nagib, Lúcia. World Cinema and the Ethics of Realism. Continuum, 2011.

27. Negt, Oskar, and Alexander Kluge. Public Sphere and Experience: Analysis of the Bourgeois and Proletarian Public Sphere. Translated by Peter Labanyi, Jamie Owen Daniel and Assenka Oksiloff, U of Minnesota P, 1993.

28. Niven, Bill. Facing the Nazi Past: United Germany and the Legacy of the Third Reich. Routledge, 2002.

29. Orvell, Miles. Empire of Ruins: American Culture, Photography, and the Spectacle of Destruction. Oxford UP, 2021.

30. Paterson, Tony. “Nuremberg: Germany’s Dilemma over the Nazis’ Field of Dreams.” The Independent. 1 Jan. 2016, www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/nuremberg-germany-s-dilemma-over-nazis-field-dreams-a6793276.html.

31. The Power of Emotion [Die Macht der Gefühle]. Directed by Alexander Kluge, Kairos-Film and Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen, 1983.

32. Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. Edited and translated by Gabriel Rockhill, Continuum, 2004.

33. Rentschler, Eric. “Remembering Not to Forget: A Retrospective Reading of Kluge’s Brutality in Stone.” New German Critique, vol. 49, Winter 1990, pp. 23–41, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/488372.

34. Rothberg, Michael. Multidirectional Memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the Age of Decolonization. Stanford UP, 2009.

35. Rutschmann, Paul. “Vergangenheitsbewältigung: Historikerstreit and the Notion of Continued Responsibility.” New German Review, vol. 25, no. 1, 2001, pp. 5–19.

36. Simmel, Georg. “The Ruin.” The Hudson Review, vol. 11, no. 3, Autumn 1958, pp. 371–85, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/3848614.

37. Spotts, Frederic. Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics. The Overlook Press, 2003.

38. Stern, Ralph. “Cinema and Berlin’s Spectacle of Destruction: The ‘Ruin’ Film, 1945–50.” Architectural Association School of Architecture, no. 54, Summer 2006, pp. 48–60.

39. Triumph of the Will [Triumph des Willens]. Directed by Leni Riefenstahl, Reichsparteitag-Film. Distributed by Universum Film AG, 1935.

40. von Moltke, Johannes. “Ruin Cinema.” Ruins of Modernity, edited by Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle, Duke UP, 2010, pp. 395–417.

41. Wenzel, Eike Friedrich. “Construction Site Film: Kluge’s Idea of Realism and His Short Films.” Alexander Kluge: Raw Materials for the Imagination, edited by Tara Forrest, Amsterdam UP, 2012, pp. 174–90.

42. Young, James E. At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture. Yale UP, 2000.

43. Zelnhefer, Siegfried, editor. Zeppelin Field: A Place for Learning. City of Nuremberg, 2017.

Suggested Citation

Guerin, Frances. “Re-presenting Histories: Documentary Film and Architectural Ruins in Brutality in Stone.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 21, 2021, pp. 13–34, https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.21.01

Frances Guerin teaches Film, Art and Visual Culture at the University of Kent. She has written extensively on questions of memorializing the past through images and art objects. She is author of multiple books and articles, including Through Amateur Eyes: Film and Photography in Nazi Germany (University of Minnesota Press, 2011), The Image and the Witness: Trauma, Memory and Visual Culture (Columbia University Press, 2007) and, most recently, The Truth Is Always Grey: A History of Modernist Painting (University of Minnesota Press, 2018). She also recently edited a special issue of the Journal of European Studies on “European Photography Today” (Vol. 47, no. 4, December 2017). Her monograph on the contemporary American painter Jacqueline Humphries is forthcoming from Lund Humphries. She is currently working on a project on the role of art in the transformation from industrial to postindustrial landscapes in Europe.