Digital Opportunities for Feminist Film Historiography: Insights from the Reframing Vivien Leigh Project

Lisa Stead

Abstract

This paper discusses some of the key methodological challenges emerging from the AHRC project Reframing Vivien Leigh: Stardom, Archives and Access, led by PI Dr. Lisa Stead at the University of Exeter. This twenty-month project examined how the legacies of screen star Vivien Leigh are archived and curated by a range of public institutions in the South West of England, taking audiences behind the scenes of local archives and museums. The paper reflects on how researching within rural heritage centres and volunteer run archives encourages the introduction of new voices and new case studies within women’s film history, by encompassing the archival labour of a network of volunteers, amateurs and professionals within a broader heritage sector whose historical actions and choices produce alternative kinds of women’s film history. It reflects in turn on the challenge involved in finding new ways to present these histories in interactive, digital and physical forms for audiences beyond the academy and to make meaningful impact from this kind of research.

Dossier

Introduction

This paper discusses some of the key methodological challenges and opportunities emerging from the AHRC ECR Fellowship project Reframing Vivien Leigh: Stardom, Archives and Access(RVL). It focuses in particular on the rich potential of digital humanities methods for producing new public-facing outputs in the work of feminist film historiography and facilitating greater access to archival methods and findings within women’s film history.

The RVL project ran for twenty months in 2019–20 and was based at the University of Exeter, led by the author as Principal Investigator with the support of Research Assistant Becky Rae. The project explored how the legacies of screen star Vivien Leigh are archived and curated by a range of public institutions in the South West of England. I utilised original oral history research and hands-on work within a range of historical collections, and co-curation and public exhibition practices to create a new digital archive. The project outputs—including journal articles, a monograph and a range of new digital resources—illustrate the ways in which star archives and those responsible for creating and curating them are a vital part of the work of feminist film historiography.[1]

By working with materials at Topsham Museum and the Royal Albert Memorial Museum (RAMM) in Exeter and with other regional partners such as The Bill Douglas Cinema Museum (BDCM) and the Fashion Museum Bath, RVL applies digital methods to map and visualise the histories of the collections and their interconnections over time. These methods are used to illuminate new stories about the meanings and uses of Leigh’s stardom for South West audiences. In this regard, RVL offers a new interpretation of a classical cinema from a uniquely archival perspective. It interrogates stardom on different terms, using digital tools to take public users behind the scenes of local archives and museums. In doing so, it examines the collections and curatorial practices that have built up around Vivien Leigh that make a global cinema icon distinctly local. The vernacular presence of stars as archival subjects in local and regional heritage spaces “reframes” them as part of a diverse network of community-specific creative labour and curation. In this way, the project breaks with a conventional focus on star image as the primary site of meaning and analysis and generates a new critical and practical model for “reframings” of other female stars and interconnected curatorial figures in the history of women and film.

In this paper, I argue for the importance of digital methods at all stages of this kind of research. My aim is to illustrate how such methods can alter the way we think about archival work in feminist film historiography. They do so by encouraging us to foreground the story of archival process in order to make space for new perspectives, new modes of labour and new figures in women’s film history.

A South West Star History

Some brief context on Vivien Leigh and her regional connections is, of course, necessary here. Leigh was a transatlantic film and theatre star. She was born and spent most of her life in England while working in both Hollywood and the British film industry. Her association with the South West of England is primarily a result of her 1932 marriage to the barrister Herbert Leigh Holman whose family had deep roots within the region. This in turn connected her with Dorothy Holman, her sister-in-law, who founded Topsham Museum in 1967 as a community archive for Topsham residents. Materials from Leigh’s films and private life (such as costumes, dress items, letters, images and film props) were donated to the museum by Leigh’s daughter and Holman’s niece, Suzanne Farrington, and Holman left the site to Exeter City Council upon her death in 1983. It was then run by local volunteers.

Figure 1 (left): Vivien Leigh artefacts on display at Topsham Museum. The bust on top of the drawers depicts Leigh’s sister-in-law Dorothy Holman. Figure 2 (right): The replica Gone with the Wind nightdress held by Topsham Museum on display at the Reframing Vivien Leigh project launch and exhibition at the University of Exeter in February 2020. Author’s photos.

While Leigh never lived in the town, her indirect familial connection from the early years of her acting career made her a highly visible part of the museum’s collections (Figure 1). Most prominent amongst the Leigh artefacts on display is a nightdress costume from the set of Gone with the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939), created by costume designer Walter Plunkett (Figure 2). Other dress artefacts belonging to Leigh have also found their way to nearby museums. RAMM in Exeter holds a petite black broadtail dress, circa 1950, a glamorous evening dress designed by Harald of Mayfair and accompanying letters about their donation from Leigh’s daughter (Figure 3). The Fashion Museum Bath also holds dress artefacts donated by Farrington in the 1960s.

Figure 3: A page from a letter from Vivien Leigh’s daughter, discussing the donation of dresses to museums in Exeter written in 1976. Source: RAMM. Reproduced with kind permission.

Methods and Methodologies

Relatively little work has been produced within film studies on how heritage institutions have collected, arranged and made use of the material legacy of women’s film stardom. Conventional critical discourse focuses predominantly on the findings rather than the process of archival research, with scholarship telling “a story about what you found, but not about how you found it” (Kaplan 103). With the RVL project, the aim was to draw upon approaches in women’s film historiography that use the archive as a way to review “received notions of what and who counts in film history” (Callahan 3). The project considered what Antoinette Burton describes as the “backstage of archives” (7). This meant extending women’s film histories to more directly include archivists and archival process, but also continuously documenting archival research challenges and experiences on the project website in “research story” exhibition pages.

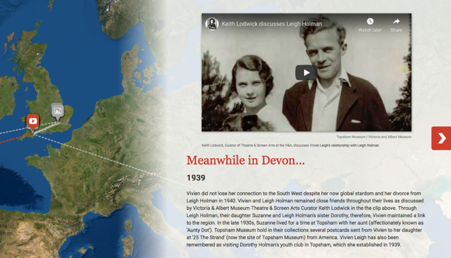

In designing the project with these aims in mind, I employed a mix of oral history approaches—focusing on recorded interviews with museum staff, curators, archivists and volunteers—and archival research, comparing materials from regional collections with Leigh’s two major archives held in the British Library and the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A). Digital methods were then employed to document findings within a new digital archive and to make the research findings and process accessible to a range of audiences, both academic and public. To achieve this, the project utilised three interlinked digital tools. A new Omeka site (Figure 4) was created to disseminate information about the project, its research programme and results. This included digital exhibitions focusing on specific source materials, high-resolution photography and photogrammetry of artefacts (Figure 5). An interactive digital map (Figure 6) was built with StoryMapJS, also hosted on the Omeka site, to allow users to explore the stories and themes surrounding the archival materials. Finally, an original podcast series (Figure 7) was created to discuss the meanings of women’s star heritage for different communities and audiences. This included interviews with curators, fans, collectors and researchers.

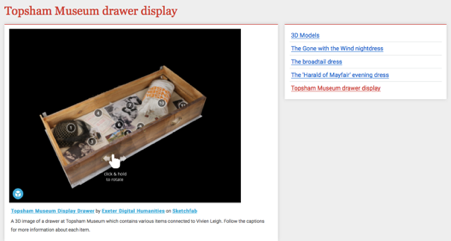

Figure 4 (above): A screenshot of the landing page banner for the Reframing Vivien Leigh website. Figure 5 (below): A screenshot of an example of photogrammetry of artefacts from RAMM and Topsham Museum hosted on the Reframing Vivien Leigh site. This model shows a display drawer from Topsham Museum. Users can rotate and zoom in to examine different portions of the image.

Figure 6 (above): A screenshot of an image of the Reframing Vivien Leigh Storymap charting Leigh’s connections to the region over time. This slide includes a video essay with commentary by V&A Theatre & Screen Arts Curator Keith Lodwick. Figure 7 (below): A screenshot of Episode 1 of the Reframing Vivien Leigh podcast series hosted on the project website. The series is narrated by Becky Rae and features original artwork by Lisa Stead to accompany each episode.

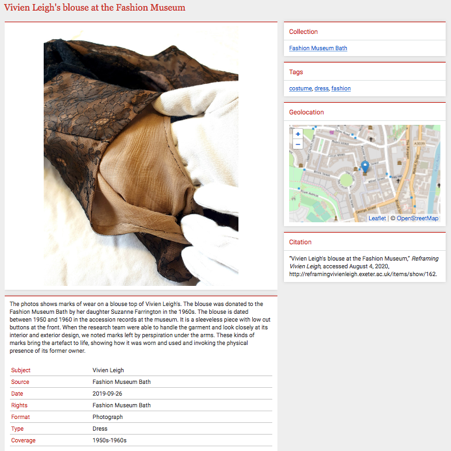

Data for the Omeka archive was accumulated from research within the UK-based archives of Vivien Leigh. This involved working hands-on with materials such as Leigh’s appointment diaries, and her personal, business and household correspondence or documentation. Interviews were also conducted concurrently with curators and volunteers at the V&A, Topsham Museum, RAMM and the BDCM in order to acquire new networked knowledge about the acquisition histories of different artefacts and archival materials. (Extracts from these interviews can be found in short video essays hosted on the project website). Still photography, using a Canon EOS 1300D camera, was undertaken at each collaborating institution to create records for the Omeka archive. Based on this compilation of material, metadata was entered into the Omeka site over several months using Dublin Core, a digital cataloguing tool. This enabled me to create a new catalogue, with each individual record consisting of a photographic image of an artefact, its location and details of the research process. Each record was accompanied by metadata giving date, location, collection, tags and a range of other categories, and explanatory and interpretative critical text (Figure 8 is one such example). Once the site had been populated with these materials, each entry was organised into collections (grouped for each museum/archive), themed exhibits and a location map.

Figure 8: A screenshot of an entry in the RVL Omeka archive cataloguing an image of Vivien Leigh’s blouse held at the Fashion Museum Bath. The image shows sweat marks on the fabric.

The research team then undertook the first stage of practical work with RAMM, in collaboration with the University of Exeter Digital Humanities Lab, in order to produce 3D models of the Vivien Leigh dress artefacts held on-site at the museum (Figure 9) and off-site at the Ark storage facility (Figure 10). The textures of furs, silks and reflective embroidery made it difficult to produce images from varied angles that could be easily matched using Agisoft Photoscan software. This software amalgamates hundreds of images of an object from different angles to produce one overall 3D model. The team had to find practical solutions to this issue, constructing a new rotating plinth for photographing materials of this size in a more stable, more easily measurable form, reducing the amount of movement of fabric to enable different images to be matched up (Figure 11). The research team undertook repeated visits to Topsham Museum where, working with volunteer collections manager Rachel Nichols, 3D models were produced, including a display drawer of artefacts (as depicted in Figure 5) and the Gone with the Wind nightdress.

Figure 9: Behind the scenes at RAMM shooting Vivien Leigh’s broadtail dress. Author’s photo.

Figure 10: Behind the scenes at the Ark. Assistant Curator Shelley Tobin shows the research team how Vivien Leigh’s dresses are stored and cared for. Author’s photo.

Figure 11: A photograph taken by the RVL research team while setting up the Harald evening dress for photogrammetry behind the scenes at RAMM. Author’s photo.

For the nightdress costume, my initial approach was to try to fill the gaps in knowledge of its provenance by cross-referencing archival materials from Topsham Museum, RAMM, the British Library and the V&A. Leigh’s V&A papers yielded details about her acquisition of the dress in personal correspondence with Laurence Olivier, alongside details about dress storage and cleaning from her business and household correspondence. Dorothy Holman’s diaries, held at the Devon Heritage Centre, offered some detail about her interactions with Leigh with regard to the museum, while further afield the David O. Selznick collection at the Harry Ransom Centre in Texas offered memos from the set of the film, where Selznick and the wardrobe department made direct mention of Leigh taking the dress.

I then turned to address the labour of the curators who had acted to retain and preserve the dress. Through oral history interviews with current curatorial staff and research within their paper collections, the work of other figures emerged. This included the work of dress collectors Freda Wills, who may have been involved in moving Leigh artefacts between Topsham Museum and RAMM, and Ann McMenamin, the volunteer steward who had rediscovered the nightdress at Topsham Museum in the early 1990s and worked to conserve and display the item.

Once this material had been collated and metadata added to the Omeka site, the focus moved to producing new resources for the collaborating institutions, starting with the Storymap. StorymapJS is open source software that enables digital maps to be built and customised with integrated multimedia. The platform privileges visual and spatial/temporal interpretations of research data. It can assist in visualising an historical narrative over time and space in a manner well-suited to the nightdress case study. The RVL Storymap also acted as a host for the final 3D model of the nightdress (Figure 12), giving users the opportunity to experience the artefact in close detail by rotating the image and zooming in to different sections in high resolution detail—effectively removing the barrier of the museum display case.

Figure 12: A screenshot of the finished 3D model of the Gone with the Wind nightdress at Topsham Museum.The final component of the research was the creation of the project podcast. As a purely sonic format, the podcast series makes the project available to users for whom visual interfaces are less appropriate. The research team designed the series to offer, in effect, an enhanced virtual experience of museum and archive spaces. We used spoken narration and on-site recordings to shape each episode and featured the voices of curators and experts who are not typically available to visitors to the museum site. To populate the episodes, interviews were conducted over several months with curators and volunteers from Topsham Museum, RAMM, the BDCM and the V&A, as well as a number of other collectors and fans who have been highly active in archiving Leigh materials. Five episodes in total were scripted and edited by Rae, who acted as the narrator for each episode. The final episode brought together the voices of various curators to reflect in greater detail on archival process, while the first four focus in turn on a single archival artefact from each collaborating institution: a dress, a vinyl record, a costume and an outfit worn to a theatrical premiere. These are used as starting points for unravelling stories of how Leigh’s career and private life had intertwined with local or international dress histories, heritage history and histories of collecting and preserving female film star memorabilia.

Digital Tools for Women’s Film History

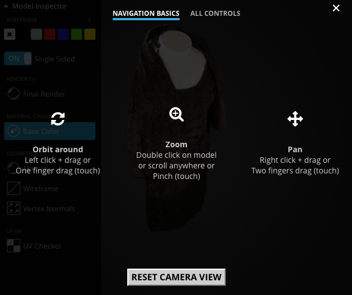

Jeanette Hall suggests that digital technologies can be “utilized to create useful platforms that can highlight feminist methodologies and epistemologies” (2). Digital methods allow us to stage new interventions in dominant film histories and the history of women and film (as figures other than performers and filmmakers). Digital methods offer new narratives of alternative articulations of agency in shaping and materially collating these histories on different terms. Importantly, digital methods have the potential to disseminate knowledge more broadly than conventional scholarly publication platforms, facilitating greater “communication between the humanities and the public” (Liu 497). For a project like RVL, digital methods have enabled research data to be processed and presented in innovative formats to create a new, smaller scale, digital archive, which offers future users a searchable, critical database of materials. I follow Phillips and Osmond here in suggesting that “acknowledging and working with digital archives”—or in this case, creating a new one—“does not diminish traditional archival research” (289). Methods employed in the project seek to retain aspects of the “aesthetic, sensorial and embodied experience” of archival and museum encounters (289), where 3D models of artefacts in particular enable users to alter their vantage point, move closer to examine smaller details and gain an impression of depth and density that are arguably less easily communicated in a more standard 2D image of an artefact (Figure 13).

The use of open source software like Omeka and StoryMapJS have enabled me to produce a new archive for Leigh materials, framed through their regional significance, displacing a primary focus on her film work and star image that allows different narratives to come to the fore. But there are also challenges and restrictions that come with the use of these tools. Hall has noted the limitations of Omeka from the perspective of the user, for example, citing the “neat but not-so-imaginative presentation of content” which “makes basic Wordpress or Weebly sites seem like better content presentation options” (8). She highlights a key distinction between the two kinds of platforms but underlines the “hierarchical” structure of the latter (8).

Figure 13 (above): A screenshot of instructions for users to manipulate the 3D model of Vivien Leigh’s broadtail dress. Figure 14 (below): A screenshot of the map function on the RVL website showing artefacts connected to the Topsham region.

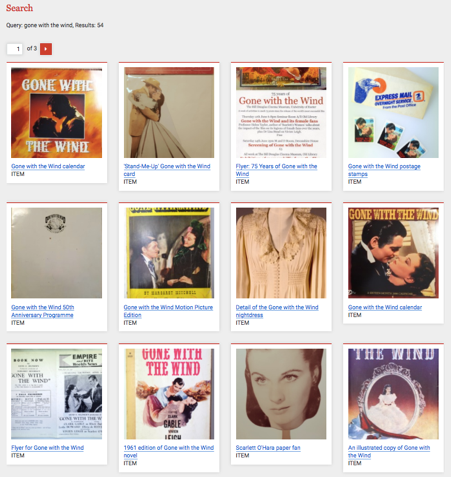

For a project like RVL,Omeka’s structure was valuable for its ability to offer two different kinds of user experiences that both utilise and break away from hierarchy. On the one hand, the platform offers users a highly guided experience of accumulated archival data through exhibition functions and bounded collection functions, which gathers data together in linear presentation formats and within institutional categories. On the other hand, Omeka offers users the chance to create their own pathways through the material in the form of add-on features, including maps (Figure 14), tags and search functions. In this way, a search for a familiar keyword associated with Leigh—the title of a film, for example—will bring up hits for a variety of artefacts which enable users to view photography, video, and 3D images, and to read critical interpretations of the artefacts and their history, but also, crucially, to see the process behind their acquisition and retention. A search for “Gone with the Wind”, for example, brings up fifty-four hits collating artefacts from four different collections and exhibitions (several of which feature accounts of work behind the scenes from different archives), interviews with curators and images of conservator and accession records (Figure 15). Such results do not erase Leigh but instead reframe her according to these alternative, regionally inflected vantage points and place her within a network of the histories of other female figures responsible for preserving material film histories.

Figure 15: A screenshot of the hits for a search for “Gone with the Wind” on the RVL site.

Across the timeline of the project, a range of public-facing events and activities were organised at which digital materials were showcased. These included a public exhibition, attended by the general public and members of Vivien Leigh’s family, and a two-day international conference held in February 2020. The digital resources launched at the RVL events offer longer lasting engagement opportunities for public audiences, reaching beyond those able to attend such events in person. While the conference and exhibition saw a combined footfall in the region of one hundred people, with users drawn particularly to the display of 3D models on large touch screen monitors, website and podcast hits have been significantly higher and continue to rise over time. The project’s Twitter feed (@ReframingVL) works to keep digital pathways open and visible for a wide range of users, leading them back to the Omeka site by regularly showcasing its various interactive features and stories. Perhaps now more than ever, as public heritage spaces remain indefinitely inaccessible as a result of the Covid-19 global pandemic, a virtual platform through which to interact with resources is an invaluable output from this kind of research. Indeed, Topsham Museum currently has plans to use the 3D models as part of a virtual tour to enable visitors to explore the museum during its temporary closure as a direct result of the pandemic.

The RVL project illustrates how digital methods can significantly enhance the telling and retelling of female star histories. Digital approaches can assist in bringing greater visibility to the work of curators, heritage workers and other less visible figures in women’s film history and help us to think about female film stardom in vernacular terms. The project alsohighlights the benefits of reconceiving more traditional monograph-led historiography projects as networked and simultaneously digital enterprises. Here, digital outputs can enrich and complicate rather than supplement or merely support written outputs. In turn, this helps us to conceive of archival process (both in terms of the historical labour of archivists and the archival labour of the researching academic) and archival findings as equally important, making both more visible in the outputs of our research and bringing feminist historiography to different users and audiences.

Notes

[1] My monograph Reframing Vivien Leigh: Stardom, Gender and the Archive is forthcoming with Oxford University Press.

References

1. Burton, Antoinette. “Introduction: Archive Fever, Archive Stories.” Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History, edited by Antoinette Burton, Belknap P of Harvard UP, 2004, pp.1-24.

2. Callahan, Vicki. “Introduction: Reclaiming the Archive: Archaeological Explorations toward a Feminism 3.0.” Reclaiming the Archive: Feminism and Film History, edited by Vicki Callahan, Wayne State UP, 2010, pp. 1-8.

3. Farrington, Suzanne. Letter to Dorothy Holman. 1976. Royal Albert Memorial Museum, Exeter.

4. Gone with the Wind. Directed by Victor Fleming, performances by Vivien Leigh, Clark Gable and Olivia de Havilland., Selznick International Pictures, 1939.

5. Hall, Jeanette. “Using a Feminist Digital Humanities Approach: Critical Women’s History through Covers of ‘Black Coffee’.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women’s Studies, vol. 38, no. 1, 2018, pp. 1-23, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5250/fronjwomestud.39.1.0001.6. Kaplan, Alice Yaeger. “Working in the Archives.” Yale French Studies, vol. 77, 1990, pp. 103-16, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/2930149.

7. Liu, Alan. “Where Is Cultural Criticism in the Digital Humanities?” Debates in the Digital Humanities, edited by Matthew K. Gold. U of Minnesota P, 2012, pp. 490-509.

8. Phillips, Murray G. and Gary Osmond. “Australia’s Women Surfers: History, Methodology and the Digital Humanities.” Australian Historical Studies, vol. 46, 2015, pp. 285-303, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/1031461X.2015.1044757.

Suggested Citation

Stead, Lisa. “Digital Opportunities for Feminist Film Historiography: Insights from the Reframing Vivien Leigh Project.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, Archival Opportunities and Absences in Women’s Film and Television Histories Dossier, no. 20, 2020, pp. 191–204, https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.20.14.

Lisa Stead is a Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Exeter. She has published on adaptation, interwar women’s cinema, fan magazines, location filming histories and gendered audiences. She is the author of Off to the Pictures: Women’s Writing, Cinemagoing and Movie Culture in Interwar Britain (EUP 2016) and co-editor (with Carrie Smith) of The Boundaries of the Literary Archive (Routledge, 2013). Her latest book, Reframing Vivien Leigh: Stardom, Gender and the Archive, is forthcoming with OUP. She is PI of the AHRC ECR Fellowship Project Reframing Vivien Leigh: Stardom, Archives and Access (2019-2020).