Researching Black Women and Film History

Agata Frymus

Abstract

My project (Horizon 2020, 2018–20) traces Black female moviegoing in Harlem during the silent film era. The main challenge in uncovering the women’s stories is that historical paradigm has always prioritised the voices of the white, middle-class elite. In the field of Black film history, criticism expressed by male journalists—such as Lester A. Walton of New York Age—has understandably received the most attention (Everett; Field, Uplift). Black, working-class women are notoriously missing from the archive. How do we navigate historical records, with their own limits and absences? This paper argues for a broader engagement with historic artefacts—memoirs, correspondence and recollections—as necessary to re-centre film historiography towards the marginalised. It points to the ways in which we can learn from the scholars and methods of African American history to “fill in the gaps” in the study of historical spectatorship.

Dossier

Any historian investigating the experiences of the marginalised will be inevitably faced with a number of challenges. The primary one is the structure of the archive itself, which has long concentrated on the privileged: on the comments of white, male, middle class writers and cultural observers. If a woman of African American heritage is present in the primary collections, either as an author or a subject, we can be almost certain she was a writer, painter, entrepreneur or a political activist. The names of acclaimed individuals such as Zora Neale Hurston, Regina Anderson Andrews and Madam C. J. Walker certainly come to mind. Their experiences, while worth examining, do not represent the vast majority of Black, working class women, who are notoriously missing from the historical record.

While white supremacy and colonialism remain the key forces that structure the archive—and, essentially, what is remembered and what is forgotten, class is an identity marker with its own implications. Annie Fee suggests that despite a well-documented interest in French cinephilia, “it is astonishing that we know so little about what it meant for working class people to go to the cinema in 1920s Paris” (163). This problem, or rather, orientation towards the highbrow, is to be found across different national contexts. Similar observations can be extended to the ordinary residents of Harlem’s Black enclave, of whom we still know little, even though a vast body of scholarship evaluates the literary and theatrical traditions conceived in the district. Race, gender and class overlap, privileging the preservation of material linked to a white, male, and usually college-educated demographic.

Every archive has its limits, and feminist historians must grapple with “the multitude, the dispossessed, [and] the subaltern” (Hartman, Wayward Lives xiii). Seeing traditional historical inquiry as deeply skewed towards the privileged group is a necessary first step in understanding, and eventually eliminating historiographic omissions. The question is: how do we notice the voices of minorities—in my case, Black women and girls—when systemic racism has excluded them from the written records, and when all we hear is overbearing silence? What methods do we use to retrieve them? How do we stop perpetuating erasure of certain stories and voices? In underlining my own struggles as a researcher, I want to gesture towards ways in which feminist scholars, but most importantly, specialists in African American history, have tackled them. Saidiya Hartman’s innovative “Venus in Two Acts” in the latter field is motivated by the necessity to contest the archive, and to recover the sparsely documented lives of Africans brought to the United States on slave ships. This notion of re-centering is important because, as historians engage with the subjectivity of the marginalised, they are doing much more than simply expanding the existing boundaries of knowledge. Studies that move away from the dominant, white narratives, are essential because they shift the collective understanding of what history actually is. They shake the colonial foundations the disciplines stand on.

Looking for Black Female Fans

We know that the positioning of Black women—in a world that is both patriarchal and racist—is neither synonymous with the positioning of white women, nor of Black men. Intersectional feminists have long looked at the overlapping hierarchies of power, and their capacity to generate unique forms of disadvantage. Although early and silent Black moviegoing has been discussed before, it was viewed as a broad practice, without a consideration of gender as a structuring factor (Caddoo; Regester; Latham and Griffiths). On the other hand, examinations of female spectatorship in the same period, including Shelley Stamp’s trailblazing Movie-Struck Girls,focuses on white women and girls. Of course, there is nothing wrong with examining certain phenomena in an exclusively white context, as long as the specificity of whiteness is acknowledged. In her essay on adolescent fandom in the 1910s, Diana Anselmo clearly delaminates the demographic that interest her as white, unmarried women in their teens or early twenties (“Screen-Struck”). By providing clear lines of demarcation, Anselmo produces a greater level of critical insight; she also avoids problematic claims that ignore the existence of Black women as moviegoers during the silent film era. But how often do we see white people for what they are: representative of only one racial positioning? Most often than not, Western paradigm allows white people to function as a shorthand for all people. Over and over, I am reminded of Richard Dyer’s poignant remark that popular culture assumes “white people are just people, which is not far off saying that whites are people whereas other colours are something else” (1-2). This is precisely where the problem lies: in assuming that white experience manages to exist beyond race—while Black experience does not—audience studies implicitly perpetuate bias.

Now, my call for inclusion encompasses feminist scholars, but it certainly is not limited to work by Black women alone. Theorists and educators from various backgrounds need to account for the gendered and multiracial ways in which media were produced and consumed. This applies particularly to white scholars who, like me, have spent years being conditioned to think of race as a concept not applicable to their own whiteness, or to the white cultural production featured in their scholarship. Race and gender have a tangible impact on defining one’s lived experience; thus—as Allyson Nadia Field reminds us—“race should matter to everyone” (“Who’s”, 135).

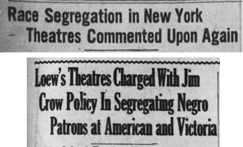

Let me turn to a specific example that illustrates how cinemagoing was shaped by racial identity as much as it was by societal understanding of femininity, and how these two categories intersected. In 1928, New York Age published a letter by Black teacher Adelaide Williams, in which she urged fellow readers to boycott the Loew’s chain of theatres (Figure 1). Williams recounted her visit to one of their flagship cinemas in downtown Manhattan, where she was refused the seat she had paid for; this was a common practice used to separate Black viewers from the white ones in the auditorium. What makes the practice notable is that in Northern States, including New York, racial segregation in cinemas was, in fact, illegal. “We proceeded quietly from the theatre so as to suffer no further humiliation before the dozen or so people standing in the lobby at the time. If this is the way this chain of theatres feel [sic] towards us then we should not enrich their coffers with our money”, she explained. Perhaps Williams felt obliged to act in accordance with patriarchal rules of respectability, preferring to lose her tickets rather than to be seen as argumentative or aggressive in public. The situation described here would be completely foreign to a white woman, but it would not align with the experience of a Black man either. Male moviegoers who encountered racist prejudice often confronted cinema personnel, or—in case of some middle-class individuals—even sued the management for mistreatment. Black women tended to have less economic, social and cultural capital than the most financially successful Black men, therefore lacking the tools to defend their rights in court. More to the point, Williams’s letter reiterates that audiences are not a monolith, and that moviegoing has rarely been a homogenous experience.

Figure 1: Headlines from African American periodical New York Age. Top: 27 May 1922, 6 (“Race Segregation”). Bottom: 25 February 1928, 1 (“Loew’s”).

When I embarked on a project retracing Black female audiences in Harlem during the silent film era, I quickly encountered several obstacles. Firstly, I turned my focus to film magazines. Many publications in this genre were highly interactive, encouraging readers to write commentary, which was then published as a selection of best letters in each issue. Picture Play usually signed each fan piece with the name and address of the author, thus allowing some writers to be identified by comparing this information against the census. Despite the fragmentary nature of such data, Lies Lanckman successfully applied this method to map the demographics of those who corresponded withfive specific titles in the summer months of 1930: yet, many readers were untraceable, so unknowns remain. While it is clear that movie monthlies constructed their imagined reader as a young white woman, I was curious to see whether Black fans had contacted Picture Play to express their admiration, or dislike, for certain stars. After all, Black girls attended movie houses, and—even in the case of desegregated Black cinemas—most photoplays projected there were major Hollywood productions rather than independent race films. Certainly, it would not be strange to hypothesise that Black female spectators could find pleasure in periodicals that commodified forms of visual culture they regularly consumed.

While this seemed like a reasonable line of inquiry, it quickly became evident that the signatures assigned to each letter often lacked substantial information that would allow me to establish racial identities of their authors. To date, I did not identify any fan letters penned by African American women, or any individuals classified as “Negro” or “Mulatto” by the 1920s census. This is not to say they were not there, but simply that finding evidence of their presence is difficult. But perhaps we should not guard against the impulse to speculate, as long as the process is grounded in some archival detail. Could there be some truth in Paul E. Bolin’s statement that imagination and speculation can assist historical tools, producing unique and meaningful perspectives (111)?

My scholarly effort continued, not surprisingly, with the analysis of clippings emerging from the Black press. Magazines written for and by African Americans, especially New York Age or New York Amsterdam News, are invaluable for a number of reasons. They were embedded in Harlem’s commerce, publishing adverts for local businesses, including programmes of specific cinemas. Furthermore, articles penned by Black writers repeatedly delved into civic issues, condemning local businesses that discriminated against people of colour. Black newspapers can be illuminating, but they too have their own sets of limitations. Unlike film critics, most working-class moviegoers—except for those whose letters made it into print—seldom left a written record of their engagement with film culture. In other words, what these columns teach us is what middle-class journalists thought of the movies, and not how Black women made sense of them. Then as today, cinemagoing was part and parcel of everyday life. In utilising the popular press, we need to look out for its limits; surely, there is only so much these accounts can disclose. We do not know how often moviegoers attended the cinemas, who with, or how they squared their passion for movies with the typically racist imaginary shown on screen. When it comes to the inner lives and likes of ordinary audience members, we are still left in the dark. This is what Jane Gaines refers to when she says we can “always ask more” of the viewers of the past (3).

Scholarship on Marginalised Audiences

Anna Everett, Charlene Regester and Allyson Nadia Field have produced fascinating, pioneering works on Black film production and film criticism. Everett, for instance, investigates the role played by Black journalists, such as Lester A. Walton of New York Age, in highlighting discrimination and advocating racial progress to his readers. The focus of Field’s monograph lies on the tentative link between cinema and uplift—the strategy of progress paradigmatic of the New Negro movement. Jacqueline Najuma Stewart and Cara Caddoo use nationwide Black press to reconstruct the development of race moviegoing in the first three decades of the medium.

Black movie-struck girls of the 1920s made rare appearances in my empirical work. They glimpsed at me from the letters published by magazines, but—most frequently—from autobiographies and other recollections. I looked for information on particular individuals in the US census, to see where they lived and if any desegregated cinemas operated in the vicinity of their homes. As any historian, I stumbled across my eureka moments when I least expected them. I learnt that one specific venue in New York City hired Black personnel because I came across a death certificate of a Black woman in her early twenties, whom the document described as an usherette. I found accounts of Harlem’s leisure in volumes published in the late 1980s (Kisseloff), or in oral histories produced in earlier decades, when people with first-hand experience of silent movies were still alive to share their tales.

The type of resources I have regularly drawn on in the past tended to be criticised by peer reviewers as too insubstantial, or too incomplete to merit attention. This perspective has been changing in the last decade, as the study of historical moviegoing made tremendous strides by turning to non-traditional methods of inquiry. Laura Isabel Serna has looked at Mexican film culture through personal recollections, oral histories and family archives. More recently, Miriam J. Petty has relied on multiple autobiographies to reconstruct the spectatorship of Black children in the 1930s. Such works illuminate the lives of marginalised subjects, while also shifting the perceptions of their scholarly disciplines. What they make abundantly clear is that film history needs to encompass all types of racial and national audiences, all of whom engage with cinema in their own, distinctive ways.

Another issue worth mentioning here is the character of oral history as a research method. There is no denying that human memory is fallible, and that comments made many decades after events took place cannot be taken at face value. Can we rely on reminiscences of elderly moviegoers who are looking back at their lives, sometimes taking their interviewer sixty, or seventy years back? The effectiveness of such narratives has more to do with the manner in which things are remembered, and what that act of remembering can reveal, than about the precise situations they describe per se. Many film scholars tuned to ethnography and memory studies in addressing such issues with fascinating results (Kuhn; Treveri Gennari). They study the intricate tapestry of recollection, longing and fantasy: of what was and what could have been.

Returning to my original point: if memoirs are, as some maintain, too flimsy, then how can historians recover the relationship between Black women and cinema, especially as it goes back over a hundred years? Where else is there to look? What I want to suggest is that there is no reason to disregard memoirs because, as Liz Clarke summarises, they can help us understand wider, institutional practices (48).[1] What we need to do instead is to navigate the tension surrounding them in the production of historiographic knowledge. Amelie Hastie makes a powerful argument about the significance of the process of recentring on what she terms “the miscellany”. She writes that “women histories are inevitably dispersed across genres, forms spaces” and that our intellectual endeavours, as feminist academics, are concerned with “miscellaneous acts of collection” (229). These methods of assembly, reshuffling and engagement with miscellaneous texts are necessary to give Black women their rightful place in history.

Historians of African American Culture

Film historians can learn from the approaches developed in the field of African American history, which has long regarded the archive as an inherently contested space.[2] Perhaps we can take inspiration from Michel-Rolph Trouillot’s famous plea “to make the silences speak for themselves” (27). The remark serves as a powerful reminder that archives are institutions, with their own agendas. They are not conceived simply to record what has happened: they operate as a means of control. They govern our collective past.

Artefacts of traditional history make it notoriously difficult to reconstruct the areas of leisure, intimacy and romance. Yet, municipal records and oral testimonies drawn upon by LaKisha M. Simmons and Cheryl D. Hicks illuminate how the pleasures and restrictions of cinemagoing for Black girls often went hand in hand. Hicks’ captivating project refers to the notes compiled by white probation officers to trace the habits and pleasures of native, as well as immigrant, Black women. In accessing Black histories through white voices, she continually undermines her own sources, revealing the racist presumptions and bias inherent in the writing. From Hicks, we learn that one twenty-four-year-old African American woman was not allowed to frequent entertainment venues, especially dance halls and movie houses, as her mother considered them to be spaces synonymous with moral degradation (216).I am fascinated by Hartman’s unconventional historical inquiries, and their potential extension to other disciplines, including my own. In venturing beyond and digging deeper, Hartman developed a set of intellectual practices, which she termed “critical fabulation”. In “displacing the received or authorized account”—which, in Hartman’s work, is that of a slave trader—and by imagining what “might have been said or might have been done”, she not only brings the focus back to the enslaved, but also shows how the alleged transparency of historical sources is in itself nothing more than an illusion (“Venus” 11).

Figure 2: Innovative approaches to history writing – Hartman’s book relies on what she terms “critical fabulation”. Stewart’s work on Black audiences draws on fictional writing by African American authors.

Admittedly, academics working in the field of film history have championed innovative models of understanding racialised audiences. In order to reconsider dynamics of Black spectatorship in the first decade of the century, Stewart turned to African American fiction. Naturally, she is aware of the implications, calling it a decision “not made lightly” (Stewart 95). She produces an account in which questions and difficulties pile up. “What kind of ‘evidence’ can we mobilize to understand what happens in the mind of viewers as they watch films?”, she asks (95). Or how far can we go in assuming that one’s fan reaction would be equivalent to, or at least similar to another’s? This kind of critical attention is precisely what makes Stewart’s study Migrating to the Movies so persuasive.

As feminist film historians, we are going against the tide, because we cannot rely solely on the material favoured by the existing historical protocol. After all, this very protocol was shaped by white, patriarchal culture, with its own distinctive oppressions. “We must remember”, explain Racquel J. Gates and Michael Boyce Gillespie, “the field of film studies was designed around the centering of heterosexual white men” (13). This centring relates to both the subject matter, as well as the tools of the study. Thus, we need to build on dispersed texts, ranging from memoirs, recollections, and letters, to anecdotes and passing mentions. While such evidence might be ephemeral or fragmentary, it is essential in our pursuit of bringing the marginalised to the fore.

Let me conclude by going back to Hartman’s remarks on counter-readings and Black history. An eloquent writer, Hartman (12) explains the complex and often multifaceted nature of investigating what is otherwise an “unrecoverable past”. The resulting narratives are riddled with contradictions, because they are “written with and against the archive” (Hartman 12). Perhaps it is time for feminist film scholars, to fully embrace writing against the archive too.

Acknowledgement

This article was produced as part of Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, Marie Skłodowska Curie grant agreement no. 792629, Black Cinema-Going.

Notes

[1] Clarke makes this argument specifically in relation to work by female screenwriters, but I found it applicable more broadly.

[2] For a more thorough discussion of the ways in which historians of African past engage with archives, and their limits, see Helton.

References

1. Anselmo, Diana. “Screen-Struck: The Invention of the Movie Girl Fan.” Cinema Journal, vol. 55, no. 1, Fall 2015, pp. 1-28, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2015.0067.

2. Bolin, Paul E. “Imagination and Speculation as Historical Impulse: Engaging Uncertainties within Art Education History and Historiography.” Studies in Art Education, vol. 50, no. 2, Winter, 2009, pp. 110-23, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00393541.2009.11518760.

3. Caddoo, Cara. Envisioning Freedom. Cinema and the Building of Modern Black Life. Harvard UP, 2014, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674735590.

4. Clarke, Liz. “‘No Accident of Good Fortune’: Autobiographies and Personal Memoirs as Historical Documents in Screenwriting History.” Feminist Media Histories, vol. 2 no. 1, Winter 2016, pp. 45-60, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/fmh.2016.2.1.45.

5. Everett, Anna. Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism, 1909–1949. Duke UP, 2001.

6. Fee, Annie. “Les Midinettes Révolutionnaires: The Activist Cinema Girl in 1920s Montmartre.” Feminist Media Histories, vol. 3, no. 4, 2017, pp. 162-94, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/fmh.2017.3.4.162.

7. Field, Allyson Nadia. “‘Who’s “We,” White Man?’ Scholarship, Teaching, and Identity Politics in African American Media Studies.” Cinema Journal, vol. 53, no. 4, Summer 2014, pp. 134-40, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2014.0041.

8. ---. Uplift Cinema: The Emergence of African American Film and the Possibility of Black Modernity. Duke UP, 2015.

9. Frymus, Agata. “Mapping Black Moviegoing in Harlem, 1909–1914.” New Approaches to Early Cinema, edited by Mario Slugan and Daniel Biltereyst, Indiana UP, 2021. In press.

10. Gaines, J. “The Scar of Shame: Skin Color and Caste in Black Silent Melodrama.” Cinema Journal, vol. 26, no. 4, Summer 1987, pp. 3-21, DOI: https://doi.org/10.2307/1225187.

11. Gates, Racquel J., and Michael Boyce Gillespie. “Reclaiming Black Film and Media Studies.” Film Quarterly, vol. 72, no. 3, Spring 2019, pp. 13-15, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/fq.2019.72.3.13.

12. Hartman, Saidyia. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments. Serpent’s Tail, 2019.

13. ---. “Venus in Two Acts.” Small Axe, vol. 12, no. 2, 2008, pp. 1-14, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1.

14. Helton, Laura et al.(eds.) Social Text, vol. 33, no. 4, The Question of Recovery: Slavery, Freedom and the Archive, 2015, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1215/01642472-3315766.

15. Hicks, Cheryl D. Talk with You Like a Woman: African American Women, Justice, and Reform in New York, 1890-1930. U of North Carolina P, 2012.

16. Kisseloff, Jeff. You Must Remember This: An Oral History of Manhattan from the 1890s to World War II. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Publishers, 1989.

17. Kuhn, Annette. An Everyday Magic: Cinema and Cultural Memory. I. B. Tauris, 2002.

18. Lanckman, Lies. “In Search of Lost Fans. Recovering Fan Magazine Readers.” Star Attractions, edited by Lies Lanckman and Tamar Jeffers McDonald, U of Iowa P, 2019.

19. Latham, James and Alison Griffiths. “Film and Ethnic Identity in Harlem, 1896-1915.” Hollywood and Its Spectators: The Reception of American Film, 1895-1995, edited by Melvyn Stokes, British Film Institute, 1999, pp. 48-50.

20. Petty, Miriam J. Stealing the Show: African American Performers and Audiences in 1930s Hollywood.U of California P, 2016.

21. “Race Segregation in New York Theatres Commented Upon Again” New York Age, 27 May 1922, p. 6.

22. Regester, Charlene. “From the Buzzard’s Roost: Black Movie-Going in Durham and Other North Carolina Cities during the Early Period of American Cinema.” Film History,vol. 17, no. 1, 2005, pp. 113-24, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/fih.2005.0011.

23. Serna, Laura Isabel. Making Cinelandia: American Films and Mexican Film Culture before the Golden Age. Duke UP, 2014.

24. Simmons, LaKisha Michelle. Crescent City Girls: The Lives of Young Black Women in Segregated New Orleans. U of North Carolina P, 2015.

25. Stamp, Shelley. Movie-Struck Girls. Women and Motion Picture Culture After the Nickelodeon. Princeton UP, 2000.

26. Stewart, Jacqueline Najuma. Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Urban Modernity. California UP, 2005.

27. Treveri Gennari, Daniela. “Understanding the Cinemagoing Experience in Cultural Life: The Role of Oral History and the Formation of ‘Memories of Pleasure’.” Journal of Media History, vol. 21, no. 1, 2018, pp. 39-53, DOI: https://doi.org/10.18146/2213-7653.2018.337.

28. Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History. Beacon Press, 1995.

29. Williams, Adelaide. “Loew’s Theatres Charged with Jim Crow Policy in Segregating Negro Patrons at American and Victoria.” New York Age,25 Feb. 1928, p. 1.

Suggested Citation

Frymus, Agata. “Researching Black Women and Film History.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, Archival Opportunities and Absences in Women’s Film and Television Histories Dossier, no. 20, 2020, pp. 228–236, https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.20.18.

Agata Frymus is a Lecturer in Film, Television and Screen Studies at Monash University, Malaysia. She is the author of Damsels and Divas: European Stardom in Silent Hollywood (Rutgers University Press, 2020), as well as articles published in Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, Celebrity Studies Journal,and Journal of Cinema and Media Studies (formerly Cinema Journal), amongst others.Her work is concerned with the intersection of the issues of film history, star studies, race, and moviegoing in the past.