Towards a Latin American Feminist Cinema: The Case of Cine Mujer in Colombia

Lorena Cervera Ferrer

Abstract

This article contextualises and characterises the history and film production of the Colombian feminist film collective Cine Mujer, and analyses how its collective and collaborative practices challenged auteurism. From 1978 to the late 1990s, Cine Mujer produced several short films, documentaries, series, and videos, and acted as a distribution company of Latin American women’s cinema. Its twenty years of activity possibly make it one of the world’s longest-lasting feminist film collectives. Yet, its history is largely unknown in Colombia and abroad. Thus, the question that motivates this article is related to how to inscribe Cine Mujer in film history without uncritically reproducing the methodologies that cast a shadow on women’s cinema. Throughout its trajectory, Cine Mujer transitioned from being an independent cinematic project interested in artistic experimentation to a media organization that produced educational videos commissioned by governmental and global institutions and often targeted at marginalised women. Based on interviews conducted with some of the Cine Mujer members, the Cine Mujer’s catalogues, and its films and videos, I organise Cine Mujer’s corpus of work in three main modes of production that disrupt the role of the auteur and the centrality of the director.

Article

Bogotá, August 2018. In a candid interview that intersects the professional, personal, and political, Patricia Restrepo revisits her career as a filmmaker, which began at Grupo de Cali. This film collective was founded by Luis Ospina, Andrés Caicedo, and Carlos Mayolo, amongst others, in the early 1970s in Colombia. Although over the years several women joined, their participation, she poignantly notes, was erased in Ospina’s last film Todo comenzó por el fin (It all started at the end, 2015). “It’s complex, it’s paradoxical”, she says, recognising that it was Ospina who gave her copies of the short-lived journal Women & Film (1972-1975), through which she learnt about women’s cinema. During these years, Restrepo worked in below-the-line roles, such as sound recordist and script supervisor. She also wrote reviews that were left unsigned in the collective’s magazine Ojo al cine. Early on she realised that to further her career, she would have to find a different platform.[1] This was the case for many women in both film production and political organisations during the 1970s in Colombia. To overcome exclusion, women began creating their own platforms and joined forces to uplift each other. After leaving Grupo de Cali, Patricia Restrepo moved to Bogotá and became involved in the feminist film collective Cine Mujer.[2] From 1978 to the late 1990s, Cine Mujer produced several short films, documentaries, series, and videos, and acted as a distribution company of Latin American women’s cinema. Its twenty years of activity make it one the world’s most enduring feminist film collectives. Yet, its history is largely unknown in Colombia and abroad, despite the still crucial relevance of its productions. Broadly, the question that motivates this article is how to inscribe the corpus of women’s cinema in film history without uncritically reproducing the same methodologies that cast a shadow on marginal cinemas and alternative film practices. How do we re-write a history of Latin American political cinema that acknowledges the complexities of film collectives such as Cine Mujer?

Figure 1: The logo of Cine Mujer. Screenshot.

Recent studies of women’s cinema have demonstrated that, on the one hand, women filmmakers were either excluded or pushed out of directorial roles, particularly after the entrenchment of Hollywood’s studio system in the 1920s and the commercial development of national film industries that followed in other countries.[3] On the other hand, these studies have also shown that women’s cinema did not completely disappear, but it was and continues to be largely overshadowed. Revisionist projects have shed light on numerous women whose work in roles above- and below-the-line has been dismissed from film historiographies of Hollywood, European cinema, and even Latin American political cinema. Patricia White notes that “reclaiming women filmmakers’ work within mainstream industries and in national and alternative film movements entails the re-evaluation of concepts of film authorship and criteria of film historiography” (125). Contributing to the collective endeavour of writing the history of Latin American feminist cinema requires a similar approach which, on the one hand, disrupts the role of the auteur and the centrality of the director and, on the other hand, acknowledges the accounts of women filmmakers, interrogates the sources available, and draws from materials that have been previously neglected. In the following paragraphs, I briefly address the problems of auteurism, particularly in relation to its exclusionary practices. I propose instead alternative collaborative modes of authorship and production as the appropriate theoretical framework to look at the work of feminist film collectives such as Cine Mujer.

The consideration of the film director as an auteur emerged in the 1950s through La politique des auteurs, first published in Cahiers du Cinéma. Based on the romantic idea of the artist-director as the creative agent of a film, auteurism displaced the hitherto central role of the scriptwriter and distinguished the individually creative style of the “hommes de cinéma”, as François Truffaut called the auteurs, from the mere technical capacity of the metteurs-en-scène (27). John Caughie writes that auteurism establishes that film, although produced collectively, is “essentially the product of its director […who expresses] his [sic] individual personality” through recurrent thematic and/or stylistic elements (9). Auteurism has permeated film studies in such a way that it continues to animate a director-centred approach even when a film has been made by self-proclaimed collectives. Thus, my criticism of auteurism is not only about its sexist cult of the male personality, as other film theorists have argued, but also about the fact that it undervalues the shared creative input in a practice that is per se “collective, collaborative, even ‘industrial’” (Grant 114), and by doing so promotes the erasure of non-auteurist contributions and non-director-centred productions. In a dossier on co-creation in documentary, Reece Auguiste argues that many of those who have contributed to auteur theory have very little experience with or even understanding of the practical elements of filmmaking. He writes:

The rhetorical underpinnings of the advocates of single authorship are, more often than not, driven by an ideological commitment to an existential position vis-à-vis the production of moving images that has been popularized by film critics, journalists, scholars, and cultural historians […] who are invariably far removed from the concrete, messy, and sometimes contradictory operations of production practices. (36)

Although an alternative film culture, the political cinema tradition that emerged in Latin America in the 1950s (labelled with the umbrella term the New Latin American Cinema) failed to challenge the (under)representation of, give voice to, or involve, women, and also, although inadvertently, cast a shadow on women’s cinema. Several elements contributed to this situation. The public discourse of the revolutionary hero saw its counterpart in cinema through radical male filmmakers who made socially and politically committed films at a time when Hollywood had “monopolistic control of film distribution and exhibition” (Shohat 45). Their films provided counter-narratives, stories of liberation, decoloniality, and socialism, fulfilling the expectations of festivalgoers who, in a post-1968 scenario, still longed for change. Although many of those films were made by film collectives, the figure of the (male) director became of central importance in the narrativisation of political cinema, which adopted an auteurist approach.[4] Moreover, these filmmakers were also intellectuals who theorised about the significance of their counter-cinema and wrote manifestos that were of great value as primary sources with which to write the history of Latin American political cinema. Concomitantly, Latin American women were also making political films, increasingly so from the 1970s. Some of them, like Colombian Marta Rodríguez and Cuban Sara Gómez, are recognised, yet often marginalised, as part of the New Latin American Cinema. But so many others—including several feminist film collectives that emerged from the late 1970s, such as Cine Mujer in Mexico and Colombia, the Venezuelan Grupo Feminista Miércoles, and the Peruvian WARMI Cine y Video—are still overlooked, proving that “the revolutionary militant lens has underestimated even other forms of engagement, such as the prolonged impact of feminism on film” (Paranaguá 76; my translation).

In recent years, a growing number of scholars, primarily women, are unearthing Latin American women’s political cinema. Using a variety of methodologies and epistemologies, these studies attempt to recapture history, rediscover, acknowledge, and re-signify this invisibilised work, and restore women’s contributions to Latin American film history. Specifically, Cine Mujer has been addressed in few but important works (Lesage; Goldman; Arboleda Ríos and Osorio; Martin; Suárez). Providing varied analysis, these scholars seem to agree on the fact that some aspects of Cine Mujer’s production, such as “its modernist belief in agency, its preoccupation with oppressed groups, and strong belief in women’s power to effect change and to mobilize” (Martin 162), were inspired by both the New Latin American Cinema and second-wave feminism. These scholars also make a case for looking at Cine Mujer’s films by paying attention to both textual and extratextual elements as a way of “demonstrating the inextricability of aesthetic, formal, and social issues within the group’s history” (Goldman 247). Nuancing what has already been written, I contend that Cine Mujer was primarily influenced by and worked in alliance with the Latin American women’s movement, local women’s organisations, and its own film subjects.[5] These alliances allowed the further development of collaborative modes of authorship and production that echoed a communitarian way of operating.

This article contributes to the existent literature by focusing on how Cine Mujer’s mode of authorship and production contested auteurist and director-centred approaches, and how its films constituted new understandings of political cinema. Contrary to auteurism, feminist film collectives such as Cine Mujer “favored a collaborative rather than an individual mode of authorship” that disputed the centrality of the director’s subjectivity (Jaikumar 209). These collaborative modes of authorship and production, on the one hand, established collective and horizontal relations between the creative and technical teams and, on the other, foregrounded a practice that “speaks alongside, rather than about, the film’s subject” through relationships of trust, respect, and mutual interest (Marks 41). Formally, this approach was mirrored in Cine Mujer’s films through different visual strategies that were continuously reformulated according to an ever-changing environment, new sources of funding, and the redefinition of the collective’s politics and goals. Cine Mujer’s production is characterised by what Stella Bruzzi, drawing from Judith Butler and referring to documentary, has defined as “fluid” (1), as it derived from a dialectical relationship between the collective, women’s organisations, documentary subjects, feminist discourses, the institutions that funded its films, the reality represented, the distribution channels, and its intended audiences. Thus, Cine Mujer’s films and videos are the product of a continuous negotiation between the different parts involved in the filmmaking and distribution processes.

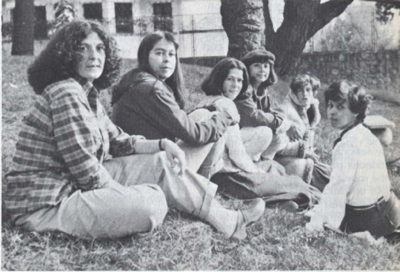

Figure 2: The women behind Cine Mujer.

Fundación Cine Mujer / Fondo de Documentación Ofelia Uribe De Acosta.

In the attempt to insert Cine Mujer within the history of Latin American political cinema, this article also draws from three other sources. Firstly, I conducted interviews with three Cine Mujer members, Eulalia Carrizosa, Patricia Restrepo, and Clara Riascos, in Bogotá in 2018. As Isabel Seguí compellingly puts it, in Latin American political cinema “women disappear in the transit from oral records to written histories, which is to say, in the passage from unofficial to official history” (11). Thus, a methodology based on oral-history interviews allows the recovery of valuable information about their personal experiences and also to implement a collaborative way of creating knowledge that is coherent with the politics of the Cine Mujer project. Accessing Latin American women’s cinema of the 1970s and 1980s is still one of the greatest obstacles for researchers who, like myself, are not based in Latin American countries. During my fieldwork, I was able to access and watch most of the Cine Mujer productions, which have been digitalised and are kept at the Fondo de Documentación Mujer y Género Ofelia Uribe de Acosta, located at the Colombian National University in Bogotá. Although the material conditions of this archive are precarious, its value for the history of women in Colombia is extraordinary. Furthermore, some of the Cine Mujer films are available on the Fondo’s YouTube channel, which contributes enormously to preserving and disseminating its works. And lastly, the different catalogues that have been published from the late 1980s to the early 2000s have been useful in providing technical details, synopsis, and information about the productions and their distribution.From 1978 to the late 1990s, Cine Mujer produced several short films, documentaries, videos, and series that were broadly concerned with providing “counter-hegemonic representations of women” (Goldman 242). Other scholars have noted that Cine Mujer’s evolution followed an increasing institutionalisation and, as a result, a de-radicalisation of its project (Goldman, Suárez). Although I do not disagree with this argument, I contend that, as time passed, its project became less artistic and cinematic and more instrumental and mediatic, but its fundamental commitment to collective and collaborative filmmaking practices and the feminist goal of changing women’s lives were maintained throughout. Cine Mujer began its trajectory making experimental short films for mainly urban middle-class audiences and continued making documentaries and other videos whose main purpose was not aesthetic but educational or informative, and were often targeted at subaltern audiences. Following this consideration, in the paragraphs below, I organise Cine Mujer’s corpus of work into three main modes of production, which correspond with three distinctive formal approaches, and which developed, with some overlapping, in three periods. During the first two periods, from the late 1970s to the mid-1980s, Cine Mujer made fictional short films and medium-length documentaries that were produced more independently and were primarily funded by FOCINE.[6] The third period took place from the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, when Cine Mujer became a production company that made educational videos and series commissioned by governmental and global institutions, such as the UN. Since it received support from not-for-profit organisations, its production was freed from the pressures of commercial success, which allowed them to focus on social and political issues. However, Cine Mujer was still bound to institutions that imposed different economic, technological, and ideological constraints, which aesthetically and politically conditioned its project in other ways.

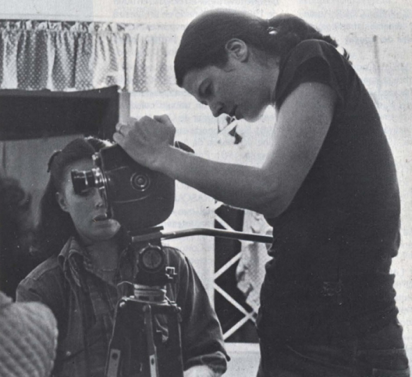

Figure 3: The funders of Cine Mujer, Sara Bright and Eulalia Carrizosa, during a shoot.

Fundación Cine Mujer / Fondo de Documentación Ofelia Uribe De Acosta.

The Cine Mujer Foundation

Colombia’s public discourse in the 1970s and 1980s was largely dominated by what is known as the Colombian conflict, which refers to the unofficial war between drug trafficking organisations, guerrillas, the paramilitary, and the Colombian government. During these decades, a very different type of history was also being written. In 1975, the UN World Conference on Women was held in Mexico City, inaugurating the Decade for Women, which had a great impact on the development of feminist and women’s organisations across Latin America. Specifically, in Colombia, from the 1970s, the political party Bloque Socialista and other organisations such as Frente Amplio de Mujeres opened up spaces for women to meet regularly and discuss women’s issues. In 1978, the First Women’s National Meeting took place in Medellín, where the slide show La realidad del aborto (The reality of abortion, 1975), made by Eulalia Carrizosa and Sara Bright, was screened as part of several activities that pushed for a public debate about the importance of decriminalising abortion. La realidad del aborto was also shown at the Colombian congress in 1979 by Liberal congresswoman Consuelo Lleras in an attempt to pass a legal proposal to decriminalise abortion. Although the law was not passed, Eulalia Carrizosa and Sara Bright decided to create a feminist film collective to serve “the women’s movement with audiovisual media” (Goldman 242).[7] Soon after the Cine Mujer foundation was legally constituted in 1978, other members joined, including Rita Escobar and Patricia Restrepo, and later on, Dora Cecilia Ramírez, Clara Riascos, and Fanny Tobón. These women were part of the collective’s core group but many other people, men and women, got involved in the productions, often on a regular basis. Unlike other recognised filmmakers from this period, and with the exception of Sara Bright who had studied film in England, these women did not have any formal education in film. The impossibility of attending film school was often the first barrier that women, even those from privileged backgrounds like the Cine Mujer members, encountered in accessing the film industry and establishing themselves as filmmakers. Since there were no film schools in Colombia at that time, the only path open to a successful career in filmmaking involved studying film abroad.[8] Instead, most of the Cine Mujer members learned about cinema by discussing films at cine-clubs and about filmmaking by working in other film collectives. For instance, Eulalia Carrizosa helped film critic and scholar Margarita De La Vega with the Cine Club at the University Jorge Tadeo Lozano and worked with filmmaker Erwin Goggel and the independent film collective Mugre al Ojo. In this private university, Clara Riascos studied communication and Patricia Restrepo studied advertising. Riascos had also worked with Erwin Goggel and was taught by militant filmmaker Marta Rodríguez, whereas Patricia Restrepo, as mentioned before, had been part of the film collective Grupo de Cali and learnt about women’s cinema through the magazine Women & Film.

How and Why to Make Cinema

Although Cine Mujer had a clear objective—to provide representations of independent and strong women—different views existed on how and why cinema should be made, in what seems to have been a negotiation between the cinematic and artistic and the feminist and political (Suárez). Some of the women in the Cine Mujer collective wanted to focus on self-consciousness and artistic experimentation and others prioritised working with subaltern women and political goals. I argue that these tensions are reflected in the two initial periods in several ways, including in the mode of production but also in formal elements such as cinematography, editing, sound, stories, characters, and the choice of genre employed in the films. During these first two periods, Cine Mujer’s most creative and experimental productions took place. Most of its first films are fictional representations that mirror the daily struggles of women from the same background as the filmmakers and capture the second-wave motto of “the personal is political” in compelling ways. The issues explored in these short films are the representation of women in the media (A primera vista [At first sight], Sara Bright and Eulalia Carrizosa, 1979), the invisible work of the housewife (Paraíso artificial [Artificial paradise], Patricia Restrepo, 1980, and ¿Y su mamá que hace? [What does your mum do?], Eulalia Carrizosa, 1981), and the gendered socialisation of children (Momentos de un domingo [Sunday moments], Patricia Restrepo, 1985). For instance, A primera vista uses different strategies such as parallel editing, colour grading and music to emphasise the contrast between a woman’s daily life and female stereotypes in advertising. The most successful of these short films was ¿Y su mamá que hace?, which was also the first of a number of films to be showcased and receive awards at the Cartagena Film Festival. Using a fast-forward effect, this short film shows a middle-class housewife performing her domestic duties. At the end of the film, a schoolmate asks her son about her job, to which he responds that she does not work but stays at home. This short film exposes one of the main issues addressed by second-wave feminism that became a recurrent theme in Cine Mujer’s filmography: the disregard for domestic work as work.

During the second period, there was greater interest in collaborating with subaltern women in the making of documentary films. When looking at counter-cinema practices, collective and collaboration are often used interchangeably. However, it is important to distinguish these two terms. In relation to Cine Mujer, I understand the collective as the group of people who worked together during all the production stages as part of the creative and technical team. This group of people discussed ideas, scripts, the mode of production, the politics of representation, the aesthetics, and the distribution collectively and horizontally, in a consensus-driven approach. In an interview conducted with Sara Bright and Eulalia Carrizosa in 1983, Bright stated that “the idea was to work collectively, without hierarchies. I think we have never voted on anything, all agreements are reached by consensus” (5). Julia Lesage also notes that “for the first several productions, the group functioned in a utopian way—making a work in which the politics and aesthetics of the piece were discussed and decided collectively at every stage of production” (328). Although individual directorial roles were credited in most of its films, throughout its production, they rotated above- and below-the-line roles, acting as directors, producers, scriptwriters, cinematographers, camera operators, sound recordists, script supervisors, editors, and so on. By continuously rotating roles, Cine Mujer showed a radical commitment to horizontality and collaboration, and rejected building up the career of a single director. Its films were not the product of an individual who expresses her/his vision. Instead, they were tools produced collectively in a continuous negotiation between reality and image, whose main purpose was to engender social change and political action. As Patricia Restrepo states, the collective’s approach remained non-auteurist, horizontal, collaborative, and feminist. She said:

We were convinced that what we wanted was horizontality. We were not interested in vertical relationships, all that seemed terribly patriarchal, and we always worked that way […]. We all were at the same level and the idea was to support each other. I think this was the basis of our feminism, in the way we established our work relations.[9]

The intricate heritage of different cultures and ethnicities and the high levels of economic and social inequality make Latin America a distinctive place. Gradually, Latin American feminists realised that their preoccupations were too confined to their class and privilege, and they fostered the need for broader women’s movements and intersectional approaches, particularly in relation to class, race, ethnicity, and sexuality. As the women’s movement became more diverse and inclusive, the women’s identities explored in the Cine Mujer films also changed, giving epistemic advantage to marginalised women. During the second period, subaltern women who were located at the margins of society, on the outskirts of the city or in the remote countryside, in their roles as mothers, wives, and artisans, became the protagonists. In addition, Cine Mujer began prioritising the documentary genre instead of fiction. Juana Suárez notes that although Cine Mujer’s familiarity with Western feminist theories “was of central importance […] Cine Mujer’s work did not represent a translation or literal application of those theories” (98). Indeed, despite the rejection of the documentary and its realist aesthetics by 1970s feminist film theory, this genre increasingly became the chosen form for Cine Mujer. Even though its documentaries employed realist aesthetics, they also experimented with performative and reflexive elements and blurred boundaries between genres.[10] For instance, Carmen Carrascal (Eulalia Carrizosa, 1982) is a 27-minute ethnographic documentary about a rural artisan from the Colombian Atlantic seaside who weaves and sells baskets made out of iraca leaves through a craft that she invented, and includes numerous close-up shots of hands and face that evoke haptic visuality and invite “the viewer to mimetically embody the experience of the people viewed” (Marks 8). La mirada de Myriam (Myriam’s gaze, Clara Riascos, 1987) is a 24-minute hybrid film that combines fictional and documentary scenes, fantasy, and reality, to tell the story of Myriam, a mother of three boys who lives in one of Bogotá’s shantytowns. Both films present women with agency within their communities and employ sophisticated audio-visual strategies that establish a ground for empathy to produce affect and effect change by relying on what Jane Gaines has referred to as “bodily effects” (90).

Figure 4: Clara Riascos during the shooting of La mirada de Myriam (Clara Riascos, 1987).

Fundación Cine Mujer / Fondo de Documentación Ofelia Uribe De Acosta.

Even though this second period is implicitly referred to as less political or even less feminist than the previous one in the special issue on Cine Mujer at Cuadernos del Cine Colombiano, Clara Riascos contends that these documentary-portraits are “powerful and effective” (11). An important aspect is that these films “perforate[d] the class boundaries between filmmaker and filmed” (Goldman 240). During this second period, Cine Mujer’s mode of production foregrounded a process of rapport-building with the film subjects through coexistence and collaboration, which proved to be particularly effective in constructing a community. Clara Riascos describes this close relationship with the subjects as “a sisterhood. It was not an intellectual or cinematic relation. That was the attitude of male filmmakers […]. We really got to know them and joined forces with them. We respected their lives, portraying them with great dignity”.[11] In relation to both Third Cinema and feminist cinema, Priya Jaikumar notes that, on one hand, collaboration exposes “the problematic identification of authors with directors, which diminishes the contributions of craft and below-the-line workers who tend to be more diverse in terms of race, class, gender, and nationality” (210). On the other hand, collaboration in feminist cinema has foregrounded “intersectional politics and experimental aesthetics, which are no less revolutionary in intent or impact” (210). Collaboration across the screen, in relation to Cine Mujer’s work, involved a negotiation between filmmaker and film subject about the mediation process and the limits of representation, which demanded an active engagement of the subjects in the filmmaking decisions. Combined with feminist politics, collaborative production practices allowed relationships of trust to be built that crossed the boundary between the public and the private, and that created an intimate space in which women felt empowered to share their personal stories. This mode of production attempted to displace the centrality of the filmmaker’s subjectivity and posed questions about enunciation. However, this approach “still disguises an unequal power relation that remains between the people on each side of the camera” (Marks 41). Thus, Cine Mujer’s mode of production did not completely break with the hierarchies of film production or entirely displace the centrality of the filmmaker, primarily because class barriers guaranteed that power still rested with the director and the filmmaking collective to a large extent. For instance, as Julia Lesage notes, the documentary subjects “could not participate in the editing”, proving that the filmmakers did not completely involve the film subjects in all stages or relinquish their agency (332). Furthermore, all Cine Mujer members came from urban middle-class backgrounds and, unlike most of their subjects, were educated and had access to resources. Despite Cine Mujer’s attempt to break with class barriers during the production of its documentaries, the collective never involved subaltern women in the core group or trained them in filmmaking.

From the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, Cine Mujer transitioned from being an independent cinematic group to a media organisation that focused on producing educational videos and series funded or commissioned by the Colombian Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Communication, and global institutions such as the UN. Although it has been argued that, at this point, “Cine Mujer had relinquished its identity as a feminist film collective, operating instead as a production company and distributor”, its videos might have been more effective as they were targeted at subaltern women who could potentially use the information to help themselves (Goldman 255). These videos were not formally innovative or experimental as in the previous periods. Instead, they mostly relied on conventional realist aesthetics, such as interviews, testimonies, voice-of-God type of commentary, and observational footage. By relying on conventional modes, Cine Mujer made its production more accessible to subaltern audiences who did not necessarily have the cultural capital with which to recognise and understand experimental films. Besides, the collaborative mode of authorship and production remained a fundamental part of the filmmaking process, even though it did not rely as much on the slow process of building relationships of trust with its subjects. Instead, Cine Mujer often worked with local women’s organisations that were willing to participate in its films since they had agendas of their own and could benefit from the greater exposure that a film can offer.

The productions of this period include those listed below. Ni con el pétalo de una rosa (Not even with the petal of a rose, 1984) is a short documentary for UNICEF which provides information about the resources available for women who have been sexually abused. Buscando caminos (Looking for ways, 1984) is a short documentary about a group of subaltern women organising themselves against the lack of infrastructure and planning in some of the fast-growing informal settlements in Bogotá. This film was made in alliance with a number of local organisations such as Bordamos nuestra realidad and Comunidad Social Amas de Casa, amongst others. Realidades y políticas para la mujer campesina (Realities and policies for peasant women, Sara Bright, 1985) is a three-episode TV programme funded by the Ministry of Agriculture that creates a dialogue between its policies and the needs of female farmers. Diez años después (Ten years later, Clara Riascos, 1985) is a documentary funded by UNICEF about women’s struggles in Peru, Jamaica, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Colombia, which was showcased at the UN World Conference on Women in Nairobi in 1985, concluding the Decade for Women. La trabajadora invisible (The invisible worker, Clara Riascos, 1987) explores domestic work from three perspectives: that of the housewife, the live-in maid, and the hourly-paid worker. A la salud de una mujer (To the health of a woman, Clara Riascos and Eulalia Carrizosa, 1990) is a thirteen-episode series produced by UNIFEM and the Dutch organisation CEBEMO about women’s physical, mental, and social health. Con la lógica de la vida (With the logic of life, Eulalia Carrizosa, 1993), funded by the UN and Fedevivienda, is a portrait of Socorro Fajardo as a community leader in her struggle for rights to housing. Magamujer (Clara Riascos, 1994) is a six-episode series on women’s rights and their struggle for equality. These videos were accompanied by a folder with textual content to support discussions and analysis. El camino de las mujeres (The way of women, Sara Bright, 1995) is a collection of interviews and testimonies on the situation of women in relation to education, health, work, political participation, and violence. The 5-Minute Project consisted of twenty-one 5-minute videos produced by the UN for the World Conference on Women, which was celebrated in Beijing in 1995. Cine Mujer contributed a short film titled Mi día (My day), directed by Sara Bright and Patricia Alvear, which follows a woman’s double day. Ciudadanía plena (Full citizenship, 1998) is a collection of interviews and testimonies that explore women’s citizenship. In addition, Cine Mujer also documented the first two feminist encuentros of Latin America and the Caribbean in Bogotá, Llegaron las feministas (The feminist arrived, 1981), and in Lima, En qué estamos (What are we on, 1983), as well as other women’s gatherings and events that took place in Colombia.

Figure 5: Clara Riascos and Sara Bright during a shoot.

Fundación Cine Mujer / Fondo de Documentación Ofelia Uribe De Acosta.

Distribution

Cine Mujer also acted as a distribution company for its own films and other Latin American films about women’s issues. Initially, its films circulated in Colombian theatres as part of the FOCINE initiative, which promoted national productions. Thus, they were viewed, as I mentioned previously, primarily by urban middle-class audiences. Furthermore, some of Cine Mujer’s productions from the first and second periods were showcased at festivals, including those in Cartagena, Bogotá, and Bucaramanga, and other international festivals such as the New Latin American Cinema International Film Festival, the Moscow Film Festival, and the Créteil International Women’s Film Festival, amongst others. Despite this, Cine Mujer’s films never received as much attention from the Latin American and international film festival circuits as those made by male directors. As Julia Lesage points out, Cine Mujer’s participation in Western women’s festivals was also limited due to the lack of knowledge of and difficulties in accessing 16mm copies of third-world films (1987). In Latin America, the emergence of a feminist cinema was not accompanied by the creation of women’s film festivals. Instead, women’s films circulated through the different feminist encuentros. This limited distribution in film festivals and the greater interest from feminist events possibly contributed to the reformulation of its entire project, and its shift from the cinematic to the political. In keeping with its aim of instrumentalising cinema to effect change, Cine Mujer also distributed its films through alternative networks, such as unions, women’s associations, schools, universities, prisons, film clubs, political parties, and other women’s events. Currently, some of its films are distributed through international organisations that promote women’s cinema, such as Women Make Movies and Cinenova.

Conclusion

The Cine Mujer project was subjected to a continuous process of interrogation and adapted according to dialectical and dynamic relations between the members of the collective and both transnational and local women’s organisations, its documentary subjects, the institutions that funded its films, the reality represented, the distribution channels, and its intended audiences. Initially, it emerged as an independent cinematic collective interested in formal experimentation through the making of short films which explored topics that were aligned with second-wave feminism. After 1981, when the first feminist encuentro of Latin America and the Caribbean took place in Bogotá, Cine Mujer showed greater interest in making documentaries concerned with representing the personal and communitarian achievements of subaltern women through collaborative practices that relied on the slow process of building relationships of trust. By doing this, its films challenged ideas about Colombian national identity and womanhood. Eventually, Cine Mujer mutated into a media organisation that was commissioned by governmental and global institutions to make educational documentaries and videos. During this last period, Cine Mujer’s production used more conventional visual strategies that, nonetheless, were more effective as didactic, informative, and political tools to disseminate useful information and knowledge to subaltern audiences. Thus, it can be argued that its project sacrificed the quest for artistic experimentation for the sake of greater community engagement. Overall, throughout its vast production, there were recurrent practices, such as the alliances between filmmakers and with feminist activists, women’s organisations, and subaltern women, that displaced the centrality of the filmmaker and contested the myth of the auteur. Particularly, the rotation of roles above- and below-the-line radically contested conventional modes of authorship and production and showed a fundamental commitment to horizontality and collaboration. Its films remained feminist inasmuch as they were all concerned with providing different representations of women, using the subjects’ voice as the main narrative device, politicising the domestic space, and promoting processes of consciousness-raising. Despite its long and diverse trajectory, and its dedication to improving the status of women, Cine Mujer’s history continues to be overshadowed by the director-centred historiographies of Latin American political cinema. Acknowledging Cine Mujer’s contributions allows us not only to inscribe Latin American women’s cinema within film history but also to learn about new understandings of political cinema based on alternative modes of authorship and production that can help us shift the ways in which we produce and analyse films.

Notes[1] Interview with Patricia Restrepo on 24 August 2018, in Bogotá. Author’s translation.

[2] Cine Mujer was also the name of a different feminist film collective from Mexico that was active between 1975 and 1986 but had no other connection to the Cine Mujer collective in Colombia. In this article, when I use the term Cine Mujer without specifying the country, I refer to the Colombian collective.

[3] Alison Butler has defined women’s cinema as those films “made by, addressed to, or concerned with women, or all three. It is neither a genre nor a movement in film history, it has no single lineage of its own, no national boundaries, no filmic or aesthetic specificity, but traverses and negotiates cinematic and cultural traditions and critical and political debates” (1).

[4] This was the case with Argentinians Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in relation to Grupo Cine Liberación, Chilean Patricio Guzmán and Equipo Tercer Año, and Bolivian Jorge Sanjinés and Grupo Ukamau.

[5] In the anglophone context, feminist cinema developed from the early 1970s through the production of films that contested patriarchal imaginaries of women, disseminated knowledge about women’s issues, and attempted to raise consciousness. These films circulated through new film festivals dedicated to women’s films and were discussed in journals and books that also contributed to feminist film theory and practices.

[6] Active between 1978 and 1993, FOCINE was a state-owned film entity that funded short films through a surcharge law (ley de sobreprecio). This law established that each film released in Colombian theatres should be accompanied by a Colombian short film or documentary, which was partly funded by a tax payable on the film ticket.

[7] Prior to Cine Mujer, women began directing films in Colombia from the late 1950s, mainly within the documentary genre, through figures such as Gabriela Samper, Marta Rodríguez, Camila Loboguerrero, and Gloria Triana, amongst others.

[8] This was the case of renowned Colombian filmmakers such as Luis Ospina, who studied cinema at USC and UCLA in California, and Marta Rodríguez, who studied ethnographic filmmaking with Jean Rouch at the Musée de L’Homme in Paris. Whereas the founder figures of the New Latin American Cinema, Fernando Birri, Julio García Espinosa, and Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, studied cinema at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia in Rome.

[9] Interview with Patricia Restrepo on 24 August 2018, in Bogotá. Author’s translation.

[10] From the early 1970s, the so-called realist debate began questioning the validity and efficacy of realist codes in feminist counter-cinema. For feminist scholars such as Claire Johnston, Eileen McGarry and Ann Kaplan, feminist cinema should depart from realist documentaries and experiment with disruptive forms. However, according to Waldman and Walker, “this wedding of the critique of realism with the goals of feminism was a crucial development that had enormous consequences for the direction of feminist film theory and the marginalization of documentary within it” (8). Other scholars, including Julia Lesage, Alexandra Juhasz, and Shilyh Warren have contested the criticism against realist aesthetics, and have revisited and acknowledged the contributions of 1970s women’s documentary to feminist cinema.

[11] Interview with Clara Riascos on 24 August 2018, in Bogotá. Author’s translation.

References

1. A la salud de una mujer [To the health of a woman]. Directed by Clara Riascos and Eulalia Carrizosa, Cine Mujer/UNIFEM/CEBEMO, 1990.

2. A primera vista [At first sight]. Directed by Sara Bright and Eulalia Carrizosa, Cine Mujer, 1979.

3. Arboleda, Ríos, and Diana Patricia Osorio. La presencia de la mujer en el cine colombiano. Ministerio de Cultura, 2003.

4. Auguiste, Reece, et al. “Co-creation in Documentary: Toward Multiscalar Granular Interventions Beyond Extraction.” Afterimage, 2020, vol. 47, pp. 34–35, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/aft.2020.471006. Accessed 5 Aug. 2020.

5. Bright, Sara, and Eulalia Carrizosa. “Entrevista con el Grupo Cine Mujer.” Arcadia va al cine, 1983, no. 4, pp. 5-9.

6. Bruzzi, Stella. New Documentary: A Critical Introduction. Routledge, 2000.

7. Buscando caminos [Looking for ways]. Directed by Clara Riascos, Dora Ramírez, and Sara Bright, Cine Mujer, 1984.

8. Butler, Alison. Women’s Cinema: The Contested Screen. Wallflower, 2002.

9. Carmen Carrascal. Directed by Eulalia Carrizosa, Cine Mujer, 1982.

10. Caughie, John, editor. Theories of Authorship. Routledge, 1981.

11. Ciudadanía plena [Full citizenship]. Directed by Patricia Alvear, Cine Mujer, 1998.

12. Con la lógica de la vida [With the logic of life]. Directed by Eulalia Carrizosa, Cine Mujer/UN/Fedevivienda, 1993.

13. Con ojos de mujer 2. Fondo de Documentación Mujer y Género, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2006.

14. Diez años después [Ten years later]. Directed by Clara Riascos, Cine Mujer/UNICEF, 1985.

15. Dueñas-Vargas, Guiomar. Con ojos de mujer. Fondo de Documentación Mujer y Género, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2000.

16. El camino de las mujeres [The way of women]. Directed by Sara Bright, Cine Mujer, 1995.

17. En qué estamos [What are we on]. Cine Mujer, 1983.

18. Gaines, Jane M. “Political Mimesis.” Collecting Visible Evidence, edited by Jane M. Gaines and Michael Renov, U of Minnesota P, 1999, pp. 84–102.

19. Goldman, Ilene. “Latin American Women’s Alternative Film and Video.” Visible Nations: Latin American Cinema and Video, edited by Chon. A. Noriega, U of Minnesota P, 2002, pp. 239–62.

20. Grant, Catherine. “Secret Agents: Feminist Theories of Women’s Film Authorship.” Feminist Theory, 2001, no. 1, pp. 113–30, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/14647000122229325. Accessed 5 Aug. 2020.

21. “Grupo Cine-Mujer.” Cuadernos del cine colombiano, no. 21, 1987.

22. Jaikumar, Priya. “Feminist and Non-Western Interrogations of Film Authorship.” The Routledge Companion to Cinema and Gender, edited by Kirstin Lené Hole, Dijana Jelača, and E. Ann Kaplan, Routledge, 2017, pp. 205–14.

23. La mirada de Myriam [Myriam’s gaze]. Directed by Clara Riascos, Cine Mujer/FOCINE, 1987.

24. Lesage, Julia. “Latin American Women’s Media.” Unpublished paper, 1987.

25. ---. “Women Make Media: Three Modes of Production.” The Social Documentary in Latin America, edited by Julianne Burton, U of Pittsburgh P, 1990, pp. 315–47.

26. Llegaron las feministas [The feminists arrived]. Cine Mujer, 1981.

27. Magamujer. Directed by Clara Riascos, Cine Mujer, 1994.

28. Marks, Laura U. Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media. U of Minnesota P, 2002.

29. Martin, Deborah. “Women’s Documentary Film: Slipping Discursive Frames.” Painting, Literature and Film in Colombian F0eminine Cultures, 1940–2005: Of Border Guards, Nomads and Women, Tamesis, 2012, pp. 162–88.

30. Mi día [My day]. Directed by Sara Bright and Patricia Alvear, Cine Mujer/UN, 1995. The 5-Minute Project.

31. Momentos de un domingo [Sunday moments]. Directed by Patricia Restrepo, Cine Mujer/FOCINE, 1985.

32. Ni con el pétalo de una rosa [Not even with the petal of a rose]. Directed by Patricia Restrepo, Cine Mujer/UNICEF, 1984.

33. Paraíso artificial [Artificial paradise]. Directed by Patricia Restrepo, Cine Mujer, 1980.

34. Paranaguá, Paulo Antonio, editor. Cine Documental en América Latina. Cátedra, 2003.

35. Realidades y políticas para la mujer campesina [Realities and policies for peasant women]. Directed by Sara Bright, Cine Mujer/Ministry of Agriculture, 1985.

36. Restrepo, Patricia. Personal interview. Conducted by Lorena Cervera Ferrer, 24 Aug. 2018.

37. Riascos, Clara. Colección Películas de Cine Mujer. Ministerio de Cultura, 1998.

38. ---. Personal interview. Conducted by Lorena Cervera Ferrer, 24 Aug. 2018.

39. Seguí, Isabel. 2018. “Auteurism, Machismo-Leninismo, and Other Issues.” Feminist Media Histories, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 11–36, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1525/FMH.2018.4.1.11.

40. Shohat, Ella. “Gender and culture of empire: Toward a feminist ethnography of the cinema.” Quarterly Review of Film & Video, vol. 13, issue, 1-3, 1991, pp. 45–84, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10509209109361370.

41. Suárez, Juana. “Gendered Genres: Women Pioneers in Colombian Filmmaking.”Critical Essays on Colombian Cinema and Culture: Cinembargo Colombia, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012, pp. 95–120.

42. Todo comenzó por el fin [It all started at the end]. Directed by Luis Ospina, 2015.

43. La trabajadora invisible [The invisible worker]. Directed by Clara Riascos, Cine Mujer, 1987.

44. Truffaut, François. “Une certaine tendance du cinéma française.” Cahiers du cinéma, no. 31, January 1954, pp. 15–29.

45. Waldman, Diane, and Janet Walker, editors. Feminism and Documentary. U of Minnesota P, 1999.

46. White, Patricia. “Feminism and Film.” Oxford Guide to Film Studies, Oxford UP, 1998, pp. 117–31.

47. ¿Y su mamá que hace? [What does your mum do?]. Directed by Eulalia Carrizosa, Cine Mujer, 1981.

Suggested Citation

Cervera Ferrer, Lorena. “Towards a Latin American Feminist Cinema: The Case of Cine Mujer in Colombia.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 20, 2020, pp. 150–165, https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.20.11.

Lorena Cervera received a BA in Journalism from the University of Valencia (2008), and a Masters in Innovation and Quality in Television Production, from Pompeu Fabra University (2009). In 2014, she was awarded with a scholarship by Ibermedia to complete a Diploma in Creative Documentary at the University of Valle, Colombia. Since 2009, she has worked as director, cinematographer, and editor of non-fiction films, and since 2015, she has taught at UCL, the University of Essex, and the University of Westminster. Currently, she is doing a practice-based PhD in Film Studies at UCL, funded by the LAHP.