Dancing & Dreaming: “Fifty Years of British Music Video” in Havana

Emily Caston and Justin Smith

On Friday 25 March 2016, The Rolling Stones held a free concert in Havana, Cuba, at the end of their South American tour. It was the first time that the band had played in Cuba. Regarded by many as the ultimate surviving rock ‘n’ roll band of the 1960s, the Stones had been pioneers of the new “pop promo” back then, and heralded the arrival of a new genre of performance videos with their 1974 bubblebath epic, It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll (Michael Lindsay-Hogg, 1974). The concert took place just days after Barack Obama became the first US president to visit the island in eighty-eight years, following a well-documented “thawing” in relations between the USA and Cuba and the formal announcement of the “normalisation” of their relations in December 2014.

In 2017, following the success of our main AHRC-funded project “Fifty Years of British Music Video” (AH/M003515/1), we were awarded a follow-on funding grant, “Dancing, Drawing and Dreaming” (AH/P01321X/1), to engage international audiences with our work. We chose Cuba, a country with an established music and dance heritage. We planned a screening, a talk, and staged a series of workshops around dance, genre and cinematography.

Aside from the evident appeal of British bands like the Stones, Caston had worked in Cuba as a producer on a Sony PlayStation commercial in 2000, using American crew flown in from Mexico because of the restrictions governing commercial exchange as a result of the US trade embargo. In 1989 she completed three months’ field work in Cuba for an undergraduate dissertation on economic development in the island, work which was undertaken at the Library of the Cuban Communist Party in 1989 using the archives of the Federation of Cuban Women, and supervised by the Department of Economic Development at the University of Cambridge. As a result, Caston had an underlying knowledge of Cuban cultural, political and economic history on which to draw in the design of an artistic collaboration between creatives in the two countries.

The Cuban music industry had been the focus of UNESCO and UN drives for some time prior to Obama’s visit, and that told us that the project might be viewed as a welcome route to developing the Cuban music industry. Cuba has a music industry recognised in the Latin American Grammy’s. And, despite its government’s post-1959 restrictions on rock music, Cuba has generally enjoyed a warm and positive relationship with international musicians, and has hosted gigs by many British artists including the Manic Street Preachers in 2001 (immortalised in Russell Thomas’s film Our Manics in Havana). The feature musical Guava Island (Hiro Murai, 2019), involving Rihanna and Donald Glover (aka Childish Gambino), was also shot in Cuba.

Cuba, too, has a vibrant and diverse dance culture, rooted both in indigenous dance forms and imported Russian ballet. Dance connections between Cuba and the UK have, like music, remained strong. In 2009, The Royal Ballet’s visit was captured in a Balletboyz documentary (Nunn), and Sadler’s Wells has collaborated in a number of productions such as Vamos Cuba! (2016) and Carmen La Cubana (2018).

Crucially, music video was also well established in Cuba as a cultural form, and remains very popular with musicians and audiences. A dedicated music video TV show, founded by Orlando Cruzata, has been running since 1997. It was set up to challenge existing prejudices towards music video and promote fledgling Cuban production, resulting, in 1998, in founding of the annual televised Lucas awards. This innovation not only recognised Cuban music video auteurs such as Alejandro Pérez, but stimulated output and prompted a national debate about the form.

Despite this progress, and as a result largely of the effects of the US trade embargo, Cuba’s film industry had been constrained by its role as a service industry. Initially, Cuban feature films were supported by the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (ICAIC), founded in 1959. But in the Special Period from 1999 on, Government funding for features was cut and native filmmakers sought overseas funding for film production. Although investment was limited, demand for Cuba as a location for foreign films grew rapidly after the release of the Oscar-nominated 1994 Cuban film Strawberry and Chocolate (Fresa y chocolate, Juan Carlos Tabío and Tomás Gutiérrez Alea). This trend impacted music video too, with Cuba used frequently as a service location, rather than a supplier to Western record labels of above-the-line creative labour. A recent example is Kylie Minogue’s video Golden directed by Sophie Muller (2018).

That situation was replicated in the dance arena where Cuba had been producing some of the best dancers in the world but often without choreographic input. The technical skill and the passion of the dancers was very high but without the money to fund new choreography, Cuban dance was limited in its growth. As Bryony Byrne explains, training choreographers in Cuba was difficult because of the social and economic restrictions: dancers are unable to access wider influences from the international community and learn from other choreographers.

There were several reasons for believing Cuba would be the ideal partner for a music video collaboration in 2018 when our funding application was approved by the AHRC. The first was that, since Raul Castro had taken over, the Cuban government had relaxed restrictions that constrained small business growth, with the consequence that small businesses in Cuba had greater freedom to collaborate. According to Philip Brenner et al., before the reform process of the 1990s, only 15% of the workforce was employed in the non-state sector—mainly private farms (121). The growth of entrepreneurship in the creative industries, in Cuba called trabajo por cuenta propia (self-employment), was perhaps nowhere more evident in the creative industries than in Fabrica, the Cuban Art Factory (FAC) created by “rocker” X Alfonso in 2014 in Havana’s Vedade neighbourhood. Cited by Time as one of the World’s Greatest Places to visit in 2019 (Cady), the FAC is a large interdisciplinary creation market and creative laboratory exhibiting contemporary Cuban art, cinema, music, dance, theatre, fine arts, photography, fashion, graphic design and architecture with a strong social and community focus.

It was timely too that, as a result of this growth, our visit received official support from British Government agencies. The loosening of US trade ties also led to a warming of relations between the UK and Cuba. Britain’s relationship with Cuba had remained largely unchanged since 1898 when it surrendered to US dominance in the region after the US ended Spanish colonial rule on the island. Whilst Fidel was still in charge, it was difficult for the UK to be seen as too friendly with Cuba for fear of jeopardizing its special relationship with the US, so the UK officially did little to challenge the series of trade embargos placed on Cuba by the USA between 1958 and 1962. But when Obama re-engaged with Cuba in 2014, the UK too warmed in its official relations with Cuba. As a result, the British Embassy planned a UK government–funded initiative through 2018 aimed at supporting economic development in the creative industries in Cuba.

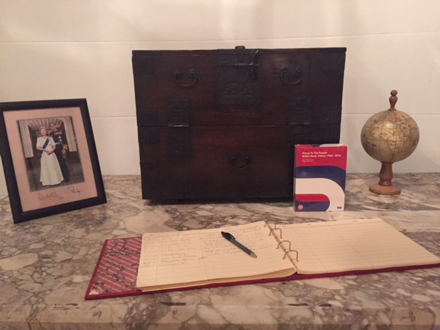

Figure 1: Official reception for the “Fifty Years of British MusicVideo” project held

at the house of Anthony Stokes, British Ambassador in Havana, on 6 April 2018:

the project DVD is on display. Photo: Justin Smith.

Furthermore, the British Council was celebrating its twentieth anniversary in Cuba that year. The British Council office in Cuba was looking to host an event to mark the anniversary. The Director of the Council in Cuba, Minerva Rodriguez invited us to develop a proposal addressing the Government’s wish to create a new vehicle like Buena Vista Social Club (Wim Wenders, 1999) to stimulate international sales and exports for the Cuban music industry. It was made clear that a music video project would be welcomed. An official reception was held for our team when we arrived in April 2018.Many Cuban music videos were performance-based, and the objective of our research trip was to stimulate creative discussion around the potential for collaboration between Cuba’s dance, film, and music cultures to create some non-performance-based dance videos. By “performance” we mean synchronised footage of the musicians’ vocal or instrumental performance. One of the most exciting developments in British music videos of the last ten years had been the rise in collaborations between choreographers and dancers from “dance culture” with filmmakers and record labels from the music video industry, such as the Wayne McGregor–choreographed and Garth Jennings–directed videos Radiohead’s Lotus Flower (2011) and Atoms for Peace’s Ingenue (2013), as well Oliver Hadlee Pearch’s videos for Jungle and the work of Holly Blakey such as Gwilym Gold’s Triumph (2015). The ideas underlying these collaborations had been explored in our panel for the FRAME Dance Film Festival 2016.

Operating as a “service film industry”, Cuban directors lacked opportunities to develop their own narratives and experiment with new cinematographic technologies and iconographies to represent those narratives to an internationalaudience. The consequence of this is that in terms of global audiences, Cuban stereotypes such as “the mulatta” (Blanco Borelli) and Havana as a construct of the Western imaginary (Kent, “(Un)Staging”; Aesthetics) were continually propagated on screen. Since most of the representations of Cuba projected, broadcast and streamed to Western audiences were scripted, directed and produced by Western creatives, the stereotypes of 1950s cars, dilapidated mafia hotels, cigars, rum and Fidel Castro persist in the Western imagination and thwart global understanding of Cuban culture. The importance of Cuban national identity in art and culture is discussed in Sandra Levinson’s essay on nationhood and identity. In Britain, music video served as a popular cultural form to raise issues of youth identity and politics in the 1980s (e.g. The Specials’ Ghost Town [1981]), and in the 2000s with Grime; a key finding of our research into music video in Britain was its function as a political tool in the development of alternative identities of Britishness.

We were cautious to avoid the kind of imperialist bias or patronage that could be attached to British Council cultural projects aimed at exhibiting art. Our visit was therefore designed in part as a field trip, in order to conduct further research about the Cuban music video industry itself. Caston had acquired awareness of cultural issues in working on British projects abroad through her work with Film London on the Microwave scheme founded in 2003 (with countries ranging from India to Georgia, Malta and Croatia), and from her experience teaching music video at Al Akhawayn University in Morocco; she had advised the British Council for Palestine about music production and music video production in the Occupied Territories in 2007. In all cases, her work dealt with issues of national identity in music video creation and exhibition arising from vastly different economic and legal (IP) arrangements. Furthermore, Caston drew on her pedagogical film practice in “creative producing”—to uncover and stimulate immanent critique—particularly for female artists and directors. The workshop was informed by Caston’s prior role as Course Director of the BA Film and Television degree at London College of Communication – University of the Arts, drawing on current theory and practice for teaching filmmaking to directors and actors.

The field trip took place between 3–9 April 2018. First of all, we needed a service company. In the global film and television industry, a service company is a production company hired by the producer(s) at the location in which they propose to film. The service company is responsible for all of the legal arrangements within the location territory—many of which will be beyond the scope of the producers who do not have relationships with the correct governmental agencies to secure permits for filming and casting in that territory. In addition, the service company provides below-the-line crew such as electricians, is responsible for organising accommodation and transportation for above-the-line crew employed by the producer and travelling with the producer. We selected Island Film Production Services and Camera House, one of Cuba’s foremost service companies for commercials and music videos, having facilitated M&C Saatchi’s commercial for HavanaClub in 2017 (Partizan).Because the goal of the project was to stimulate above-the-line talent in film, diversity and intellectual property exploitation, we sought to work with an up-and-coming director rather than an established music video director. Island Pictures nominated one of their young directors, Giselle Garcia Castro, a recent graduate of the Film School at the University of Arts in Havana, who had directed and edited music videos during her course and had worked on a number of industry videos, documentaries and dramas in an assistant role. Caston was theoretically interested in issues about how female directors articulate their voices differently.

We asked Island Pictures to research a Cuban musician who would be available at short notice to have a creative meeting with our team, would be able to issue us a licence, had material that would suit a dance piece, and who would support a collaborative endeavour such as ours. Their suggestion was leading Cuban rap artist Telmary Díaz whose album was due out later in the year. Telmary is a spoken-word musician and jazz poet who, in 2007, had received a Cubadisco (the Cuban equivalent of a Grammy award). Although rap was initially an import, in the 1990s Cuban musicians turned it into a genre of their own with samplers, mixers and albums. Unlike elsewhere in the world, Cuban hip-hop evolved independently of US influence and its lyrics and themes are distinctively different, focusing on the problems of daily life and the way that governmental decisions during the Special Period undermined objectives of the Revolution such as racial equality rather than promoting sexual exploitation and consumption. This aligned with the grime music scene in the UK, and our focus on grime as a strand in music video production of significant, but as yet unrecognised, cultural and artistic value (Caston, British).

The pathway to impact chosen was to work with the Danza Contemporánea de Cuba that director/choreographer Miguel Iglesias founded in 1959, which is one of the country’s leading dance groups. The group was chosen because they had a hybrid dance style, mixing Afro-Caribbean rhythms, jazz, American modernism, and European ballet which we believed would mean they were more familiar with the tropes of contemporary and fusion dance with which British choreographers such as Holly Blakey were working. In addition, because they had recently toured in the UK, we judged they had prior experience in collaborating with UK partners which was important given our limited timeframe. Because of our “talent development objective”, we elected to work with the company’s recent graduates rather than company directors. British director WIZ participated in a workshop run by Caston with the dancers. WIZ has directed acclaimed videos for Kasabian, Dizzee Rascal, and Massive Attack amongst others, and had been chosen by us because of his previous work with the Danza Contemporánea de Cuba in Disclosure’s Voices (2013).

Figure 2: Emily Caston (left) and Giselle Garcia Castro (right) at the rehearsal studios of the Danza Contemporánea de Cuba in Havana, Cuba, 7 April 2018. Photo: WIZ.

We began the workshop by inviting Giselle to watch a number of dance music videos from the UK. Giselle had experience working with the dancers both in Danza Contemporánea de Cuba and in Carlos Acosta’s dance foundation. Caston screened some of the dance videos from Disc 5 of the limited-edition box set—a dedicated choreography collection that she had curated which demonstrates specialist cinematographic and editing techniques for filming choreography from traditional ballet to modern dance and contemporary club dance. It includes The Chemical Brothers’ Wide Open (Dom & Nic, 2016), and Young Fathers’ Shame (Jeremy Cole, with choreography by Holly Blakey, 2015).

From Telmary’s forthcoming album Fuerz Arara (2018), Giselle selected the track “Soy el Versa” for the dancers. As well as an intriguing and rhythmic dance structure, the lyrics spoke of Telmary’s feelings for José Martí, one of the heroes of Cuban independence. Furthermore, our concern to explore issues of Cuban identity and tradition in dance led us to invite participants in our project to reflect on the evolution of genre, parody, imitation and originality, the relationship of dance to music, the nature of collaborative authorship, and notions of “identity”, “time” and “space”.

The first step was a casting session which we held at the dance company’s rehearsal studios. Giselle cast a white woman and a mixed-race woman for the reason that she felt the two women represented two pathways of Cuban social history: white Spanish colonialists and black African slaves (more than a million slaves were brought to Cuba by the European colonials). Giselle played the track to the young women. They then worked collaboratively on an improvisation. We filmed the rehearsals. This is a technique learned from Derek Jarman but useful in dance, when in an initial improvisation of the kind aimed at, a move will be instinctual and raw, and Caston wanted to capture that rawness rather than a second rehearsal simulation. She was impressed by Giselle’s encouraging the young women to reflect on the lyrics of the track, and relate those lyrics to their own experience. They were captured by the Cuban camera operator, working on Steadicam, with the Cuban first assistant director. WIZ gave occasional tips, particularly on the cinematography.

In addition to this workshop we held a screening and panel discussion with staff and students at the International Film and Television School (EICTV) focussing on the crafts of music video production, direction, cinematography and editing. The value to Caston and the AHRC team of taking our research project to EICTV was its ability to deliver impact to student filmmakers beyond Cuba. Each year around forty students from Latin America, Africa, Asia and Europe are selected to complete the Curso Regular (Regular Course).

The result of our workshop and filming in Cuba was a single-shot video for “Soy el Verso” filmed in the dance studio at Danza Contemporanea, based on an improvisation guided by Giselle. Garcia’s reflections reveal that most Cuban music videos tend to be artist-centred and that the trend of recent British music video directors working with top choreographers (from Wayne McGregor to Akram Khan) has not registered here. Inspired by the José Martí poem with which Telmary’s song opens, Giselle immediately identified rich metaphors that lent themselves to exploration through dance. We screened this single-shot video for Telmary in a meeting later that day, to invite her commentary.

The video realised a number of the trip’s ambitions. Giselle’s casting decision addressed the colonialist and patriarchal concept myth of the “sexual mulatta” found in many Latin American societies. The construction of the “mulatta” as “other” and as a transgressor of taboos was also a concept that Caston had tackled in Topher Campbell’s 1996 film she produced for Channel 4 and the Arts Council (A Mulatto Song). In her choreography, Giselle put the camera at the service of dance in having the dancers improvise whilst the cinematographer followed, like a third dancer, on his Steadicam. The single-shot video adopted the principle of a music video in which the choreography is inspired by the rhythm, melody and lyrics of the music (a principle which, as Matthew Bourne addresses in his autobiography, is anathema in the discipline of dance film). But it also drew on screendance, in putting the cinematography at the service of the dance; this has been an ambition of the most dedicated of the dancer-directors in British music video: Kate Bush, Michel Gondry, Dawn Shadforth and Holly Blakey.

As well as this single-shot video, we produced a fifteen-minute documentary capturing the process and some of the interviews that we conducted with filmmakers, teachers and students. Very little about Cuban music videos is available in English online. One of the principal interviewees was leading director Alejandro Pérez, who talked not only about his own career but the challenges for a Cuban director trying to reach international audiences. He argued that digital technology had empowered young creative talents to achieve astonishing results on their smartphones—innovation no longer requires a budget. He stated that in Cuba, access to the means of production was now open to almost all, but that the creative new wave of small businesses and creative production in Havana was still bounded by poor digital infrastructure; Cubans felt that it was holding back the tide of innovation every bit as powerfully as the historic US trade embargo.

We had not anticipated internet access as an issue. At the time of our visit, internet access was very limited in Cuba. Apart from Cuba’s famed unofficial internet, La Parquette, Cuba enabled little internet access at the time of our visit due to cost and servers. Music video streaming of the kind that British audiences are familiar were not the norm because of the high cost of internet access both for uploading new (Cuban-produced) content and of viewing or downloading it. This was cited by the students at EICTV as the main obstacle to the Cuban film and television culture. Since our visit in 2018 progress has been made.

One of the ambitions of our venture to Cuba was not only to engage with this emergent creative cluster, but to mine beneath Cuba as the tourist entity reflected in Buena Vista Social Club—a project which, whilst it stimulated tourism, has also shackled creatives on the island in a “commodification of culture”. As Marguerite Rose Jiménez comments, “[i]n Cuba as well as other tourist-dependent developing nations, local artists tend to skew their own work so that it conforms to tourists’ expectations” (222). As James Kent points out, much of the film work shot in Cuba in the late 1990s and early 2000s “emerged in the wake of what critics have described as the Buena Vista Social Club boom or phenomenon”, following the 1997 album and 1999 film which created Havana as a projection for foreign fantasies of a late twentieth-century image boom (Aesthetics 76).

Through our Cuban workshops we shared the theory and practice of music video production. We encouraged our audiences to reflect on their practices as filmmakers and dancers through the framework of collaborative authorship developed in the course of our original research, and through the theoretical conception of dance presented in Caston’s 2017 article on dance in music video in Music, Sound and the Moving Image. Using film (in Cuba) as a means of capturing these experiences provided a productive “ethnographic” method of recording what Geoffrey Crossick and Patrycja Kaszynska identify as “sensory and somatic” responses (22). These opportunities constitute what the AHRC Cultural Value Project report identifies as methods of “participatory evaluation” where the organisers and facilitators work in an immersive relationship with the audiences at cultural events, enabling the collection of experiential qualitative as well as quantitative data (127). Our documentary record of these collaborative encounters provides a lasting record of qualitative value.

The video also fulfilled Caston’s ambition to break down the barrier between “dance film” and “music video” by putting the choreography at the centre of the exercise, and by building the choreography from the lyrics of the music and a distinctively Cuban interpretation of José Martí’s legacy. Caston observed a tension between the advice of our white Western director WIZ to “stylise” the video in the fashion of British videos and objectify the female body to the “male gaze”. This Western stylisation was resisted by our Cuban director Giselle, who asserted an interpretation which figured the young female dancers as agents of their own narrative choreography and image. It endorsed the theoretical model of Caston as a creative producer and facilitator aiming to encourage practitioners to identify and articulate their own narrative and iconography, not those of the mentors or dominant nations.

The project demonstrated that academics can use their expertise to bring together artistic communities and stimulate new practices, innovation and economic development. It also illustrated the importance of academics in the creative industries reaching out to use the networks established by institutions like the British Council and British Embassies abroad. Those networks exist, but it speaks to the need to imagine practical exercises that teams can collaborate in, because it is through those tasks that most can be learned, rather than through formal interviews. It also shows the value of field research in which much can be learned. As a result of the trip, Caston returned to the UK with a much deeper understanding of the Cuban music video industry, and of the creative industries in Cuba as a whole.

References

1. Alea, Tomás Gutiérrez, and Juan Carlos Tabío, directors. Strawberry and Chocolate [Fresa y chocolate]. Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industrias Cinematográficos (ICAIC), 1993.

2. Blakey, Holly, director. Gwilym Gold, Triumph. Brille Records, 2015.

3. Blanco Borelli, Melissa. She Is Cuba: A Genealogy of the Mulata Body.Oxford UP, 2015.

4. Bourne, Matthew. Matthew Bourne and His Adventures in Dance: Conversations with Alastair Macaulay. Faber & Faber, 2011.

5. Brenner, Philip, et al. “History as Prologue: Cuba before 2006.” A Contemporary Cuban Reader: The Revolution under Raúl Castro, 2nd ed., edited by Philip Brenner et al., Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, pp. 10–51.

6. Bubbles, Barney, director. The Specials, Ghost Town. 2 Tone Records, 1981.

7. Byrne, Bryony. “Danza Contemporanea de Cuba.” Aesthetica, 2010. aestheticamagazine.com/danza-contemporanea-de-cuba. Accessed 20 Apr. 2020.

8. Campbell, Topher, director. A Mulatto Song. Channel 4/Arts Council of England, 1996.

9. Caston, Emily. British Music Videos 1966–2016: Genre, Authenticity and Art. Edinburgh UP, 2020.

10. ---, director. Dancing and Dreaming: Fifty Years of British Music Video in Havana. University of West London, 2018.

11. ---. “The Dancing Eyes of the Director: Choreographers, Dance Cultures, and Film Genres in British Music Video 1979–2016.” Music, Sound and the Moving Image, vol. 11, no. 1, 2017, pp. 37–62, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3828/msmi.2017.3

12. Cole, Jeremy, director. Young Fathers, Shame. Lemonade Money/Big Dada, 2015.

13. Crossick, Geoffrey, and Patrycja Kaszynska. Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture: The AHRC Cultural Value Project. Arts and Humanities Research Council, 2016, https://ahrc.ukri.org/documents/publications/cultural-value-project-final-report/.

14. Dom & Nic, director. The Chemical Brothers, Wide Open. Outsider/Virgin Records, 2016.

15. Garcia Castro, Giselle, director. Telmary, Soy el Verso. Telmary, 2018.16. Guerra, Nilda, choreographer. Vamos Cuba! Sadler’s Wells,2016.

17. Helman, David, director. HavanaClub commercial, “Cuba Made Me”. Partizan/M&C Saatchi, 2017.

18. Jennings, Garth, director. Atoms for Peace, Ingenue. STK Films/XL Recordings, 2013.

19. Jennings, Garth, director. Radiohead, Lotus Flower. Tickertape/XL Recordings, 2011.

20. Jiménez, Marguerite Rose. “The Political Economy of Leisure.” A Contemporary Cuban Reader: The Revolution under Raúl Castro, 2nd ed., edited by Philip Brenner et al., Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, pp. 217–29.

21. Kent, James C. Aesthetics and the Revolutionary City: Real and Imagined Havana, Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

22. ---, “(Un)Staging the City: Havana and the Music Film (2001–2005).” Hispanic Research Journal, vol. 18, no. 1, Feb. 2017, pp. 74–91, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/14682737.2016.1238163

23. Lang, Cady. “Fábrica de Arte Cubano.” Time, Greatest Places 2019, time.com/collection/worlds-greatest-places-2019/5654125/fabrica-de-arte-cubanohavana-cuba. Accessed 22 Apr. 2020.

24. Levinson, Sandra. “Nationhood and Identity in Contemporary Cuban Art.” A Contemporary Cuban Reader: The Revolution under Raúl Castro, 2nd ed., edited by Philip Brenner et al., Rowman & Littlefield, 2014, pp. 406–13.

25. Lindsay-Hogg, Michael, director. Rolling Stones, It’s Only Rock ‘n’ Roll. Rolling Stones Records, 1974.

26. Muller, Sophie, director. Kylie Minogue, Golden. Black Dog/BMG, 2018.

27. Murai, Hiro, director. Guava Island. New Regency Pictures, 2019.

28. Nunn, Michael, director. The Royal Ballet in Cuba. More4, 25 Dec. 2009.

29. Pearch, Oliver Hadlee, director. Jungle, Julia. Colonel Blimp/XL Recordings, 2015.

30. ---, director. Jungle, The Heat. Colonel Blimp/XL Recordings, 2013.

31. ---, director. Jungle, Time. Colonel Blimp/XL Recordings, 2014.

32. Power to the People: British Music Videos 1966–2016. 200 Landmark Music Videos. Thunderbird Releasing, 2018. Certificate 18. Region 2, 6 Discs, 900 minutes. Colour / PAL.

33. Renshaw, Christopher, director. Carmen La Cubana, Sadler’s Wells, 2018.

34. Rodríguez, Fidel A. “Cuba: Videos to the Left – Circumvention Practices and Audiovisual Ecologies.” Geoblocking and Global Video Culture, edited by Ramon Lobato and James Meese, Institute of Network Cultures, 2016, pp. 178–89.

35. Rodriguez, Minerva. Personal communication, 26 July 2017.

36. Telmary. “Soy el Verso.” Fuerz Arara, Telmary, 2018.

37. ---. Fuerz Arara. Telmary, 2018.

38. Thomas, Russell, director. Our Manics in Havana. Channel 4, 2001.

39. Wenders, Wim, director. Buena Vista Social Club. Road Movies Filmproduktion, 1999.

40. WIZ, director. Disclosure, Voices. Somesuch & Co/Island Records, 2013.

Suggested Citation

Caston, Emily, and Justin Smith. “Dancing & Dreaming: ‘Fifty Years of British Music Video’ in Havana.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, Dossier, Music Videos in the British Screen Industries and Screen Heritage, no. 19, 2020, pp. 184–194, https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.19.16

Emily Caston is Professor of Screen Industries and director of PRISM at the University of West London. Previously a board member of Film London (2008–2015) and Executive Producer of Black Dog Films for Ridley Scott Associates, Emily has produced over one hundred music videos and commercials. She is a member of BAFTA, has held research grants from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, and contributes regularly to the Sky Arts series Video Killed the Radio Star. She has published widely on music video and her books include Celluloid Saviours: Angels and Reform Politics in Hollywood Film (2009) and British Music Videos 1966–2016: Genre, Authenticity and Art (2020).

Justin Smith is Professor of Cinema and Television History at De Montfort University, Leicester and Visiting Professor of Media Industries at the University of Portsmouth. He is the author of Withnail and Us: Cult Films and Film Cults in British Cinema (I. B. Tauris, 2010), and, with Sue Harper, British Film Culture in the 1970s: The Boundaries of Pleasure (Edinburgh University Press, 2011). He was Principal Investigator on the AHRC-funded projects “Channel 4 and British Film Culture” (2010–2014) and “Fifty Years of British MusicVideo” (201518).