Queer Media Temporalities

Editorial

Maria Pramaggiore and Páraic Kerrigan

Queerness has always been marked by its untimely relation to socially shared temporal phases, whether individual (developmental) or collective (historical). (McCallum and Tuhkanen 6)

The 2017 promotional campaign that launched Season Nine of Logo’s award-winning reality competition TV series RuPaul’s Drag Race (RPDR) spoke directly to anxieties circulating within LGBT communities in the US and beyond as a result of the 2016 election of Donald Trump (LogoTV). More specifically, the marketing strategy asserted the programme’s timely relation to an unfolding history that seemed unrelentingly bleak. For, despite candidate Trump’s pledges to support the LGBT community, his administration immediately undertook actions that rolled back Obama-era advances. Trump reassigned the senior advisor for LGBT health in the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), fired every member of the President’s Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS, attempted to ban all transgender people from serving in the US military (later limited to a ban on those who have transitioned), and sought to rescind workplace protections for LGBT people that had been recognised under Title VII of the Civil Right Act. As we write this Introduction in late 2018, Trump’s administration announced plans to redefine gender as “biologically fixed”, which will effectively “define out of existence” 1.4 million transgender Americans in the US (Green, Benner, and Pear). Sensing the growing vulnerability of queer life at the epicentre of this gathering storm, RPDR asserted its importance to American politics and culture. Prior to the airing of the season’s first episode in March 2017, TV spots and online ads featured the tagline, “drastic times call for dragtastic measures”, with Ru Paul proclaiming “we need America’s next drag superstar now more than ever” (@RuPaul; LogoTV).

Season Nine’s self-consciousness about the political significance of queer stardom to these contemporary “drastic times” was manifested in part, and perhaps somewhat paradoxically, through an emphasis on queer history. The season’s ultimate winner, Sasha Velour, treated the show as a platform for queer resistance, celebrating drag history by embodying queer pasts and presents. One act was to channel Marlene Dietrich, the iconic figure whom Velour described as the “Teutonic bisexual” on the “Snatch Game” episode, a challenge whereby contestants showcase celebrity impersonations in a game show context. “Snatch Game” itself is an impersonation: a parody of the classic NBC game show Match Game (Frank Wayne, 1962–1991), a low-stakes competition in which contestants attempted to predict and match six (often past their “sell-by date”) celebrities’ answers to potentially provocative fill-in-the-blank questions.

The reconfiguration of this now-classic television text for a contemporary queer audience, combined with Velour’s Dietrich performance, enacted a complex and temporally layered version of what scholar Carolyn Dinshaw calls “touching across time”, which names a process of “collapsing time through affective contact between marginalised people now and then” (Dinshaw et al., “Roundtable” 178). Situated within the contexts of RPDR and “Snatch Game”, Velour’s Dietrich forged affectively erotic and comic links across decades, national contexts, and media histories, placing prewar European cinema and studio-era Hollywood alongside game show and reality TV formats. Velour’s performance also reached across contemporary media forms by embodying a film star whose career began in Weimar Germany, the historical period that (pre)occupied Season Two of Transparent (2015), Jill Soloway’s Amazon Studios TV series featuring a trans woman protagonist and her family. By doing Dietrich on “Snatch Game”, Velour simultaneously reanimated a queer historical icon, pointed to the “hidden-in-plain-sight” quality of queer media (flamboyant but closeted gay performers Charles Nelson Reilly and Paul Lynde were beloved regulars on Match Game), and reinforced a contemporary political–televisual intervention by invoking Weimar in a gesture of historiographical solidarity with Transparent.

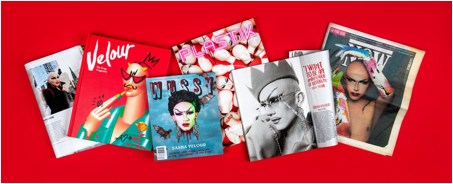

Figure 1: Sasha Velour’s pervasive media presence. Sashavelour.com. Screenshot.

Possibly as a result of this historiographic complexity, Velour—a Fulbright scholar whose Master of Fine Arts thesis was a graphic novel on the Stonewall Riots of 1969—was framed as both a narrator of queer history and a contemporary, politicised queen. After Season Nine concluded, Velour continued to engage with RPDR through her investment in queer history and its potential to speak across time. In March 2018, RuPaul publicly expressed reservations about including a transgender contestant in future seasons (several trans women had appeared on RPDR but had not disclosed their status before being selected). In response, Velour again invoked affective contact across queer pasts and presents, collapsing time and engaging in queer pedagogy from the ersatz podium of her Brooklyn drag show. Velour argued for the historicity of inclusivity: “Trans women, trans men, AFAB—which is assigned female at birth—and non-binary performers, but especially trans women of colour, have been doing drag for literal centuries and deserve to be equally represented and celebrated alongside cis men” (Weaver). Velour’s ongoing engagement expanded the fourteen-week time horizon for the programme—its own temporally oxymoronic title, Drag Race, hinting at complexities of a queer time that reserves momentum while moving forward—while also expressing “a queer desire for history” (Dinshaw et al., “Roundtable” 158) and animating Ann Cvetkovich’s archive of feelings as “a theory of cultural relevance, a construction of collective memory, and a complex record of queer activity” (Halberstam, Time 136–7).

In short, the relationship between RPDR and its reigning queen Sasha Velour highlights some potentially productive intersections between media temporalities and queer time—theorised variously as a resistance to “chrononormativity” (in Elizabeth Freeman’s Time Binds), or as an ecstatic “horizon of being” (in José Esteban Muñoz’s Cruising Utopia), as “backwardness” (in Heather Love’s Feeling Backward), and as “fashionable lateness” (in Emma Katherine Atwood’s “Fashionably Late: Queer Temporality and the Restoration Fop”). Until very recently, media temporalities were considered synonymous with the modern (though not necessarily sequential) straight time of film’s twenty-four frames per second (likened to the rhythm of the moving train by Lynn Kirby), with measurable running times and average shot lengths, and with television’s regular weekly time slots. The digital era has transformed the temporalities of media production and consumption into a far queerer and irregular set of concerns, which includes the ephemerality associated with obsolete formats (film, video, floppy disks, DVDs), the on-demand imperatives of emerging platforms and production regimes, and the asynchronous (and yet oddly predictable) consumption practices enabled by mobile computing and ubiquitous media. There are several touchstones around temporality for time-based screen media. Raymond Williams and Cecelia Tichi theorised the intimate spatiality and domesticated flow of televisual representation, yet the changing locations and contexts for the viewing of screen media, as well as narratological and industry convergences, have undermined the distinctions between cinema, TV, and video games. Films and television series stream alongside one another not only into domestic spaces but anywhere a device can travel. Audiences may make a viewing selection primarily on the basis of running time, deemphasising the distinction between formats, modes, genres of film, video, TV, and webisode. The advent of greater consumer control over viewing time, first through home viewing technologies such as the VCR and more recently through digital television “drops” (the release of an entire season at once) that enable binge watching, increasingly link media temporalities to production patterns and consumption choices rather than the material attributes of the media text. Mobile technologies and new business models have fully mediatised the daily rituals of those of us with access to technology, suspending us in seeming perpetuity in media worlds created by corporations. Indeed, those who create these entertainment environments are increasingly sounding the alarm regarding their potentially damaging and antisocial effects (Bowles).

Queer scholarship understands temporality as a disciplinary technology of subjectivity: “a technique by which institutional forces come to seem like somatic facts” (Freeman 3). If “queer” refers to “non-normative logics and organizations of community, sexual identity, embodiment, and activity” then queer temporalities “emerge [...] once one leaves the temporal frames of bourgeois reproduction and family, longevity, risk/safety, and inheritance” (Halberstam, Time 135–6). Recurring tropes of queer temporality highlight a refusal to proceed with the order of things, so to speak, and include regression (Freud), temporal drag (Freeman), and an emphasis on childhood (Stockton). In Queer Times, Queer Becomings, E. L. McCallum and Mikko Tuhkanen write, “[w]ho, developmentally speaking, are younger at heart than queers, who in the homophobic imagination are retarded at the irresponsible age of youthful dalliances, refusing to grow up, settle down, and start a family?” (6). They acknowledge the way queernesses depart from the “designated biopolitical schedule of reproductive heterosexuality” (McCallum and Tuhkanen 5), a normative biopolitical timetable—reproductive futurism—rejected by Lee Edelman’s now-classic polemic No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, which argues for a queer ethics that embraces its relation to the death drive rather than an accommodationist acquiescence to a heteronormative temporal order.

This special issue of Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media on “Queer Media Temporalities” draws upon this theoretical tradition and its rich set of concepts to explore queer temporalities that emerge within or may be generated by our engagement with time-based screen media. In its focus on specific media forms, it joins work by Kate Thomas and Jodi Taylor, who explore the intersections between queer time and the formal parameters that govern the time-based genres of poetry and music. Our questions here relate to both resistances and transformations enabled by the encounter of queer with (old and new) media temporalities. We are interested in the way games, television, video and experimental film enable or demand a queer renegotiation of time. Our contributors examine the role that archival temporalities play in the representation of queer lives in history and the imaginative landscapes of games. They consider whether reproductive futurism can help us to think about the queer life cycle of a television series and its characters. How does queer childhood, or “growing up sideways” (Stockton) resonate with film form for filmmakers invested in a nonreproductive queer genealogy? What is the relationship between media obsolescence and the “queer art of failure” (Halberstam, Art)?

The issue opens with two articles that productively interrogate the role of the archive in the construction/erasure of black queer identities in history and of queer women in video games. In their dialogical essay (a form that itself challenges academic norms) “Hiraeth, or Queering Time in Archives Otherwise”, Onyeka Igwe and JD Stokely talk through the danger and disappointment that queer black artists experience when they encounter the archive. Theorising reflectively on and through their creative practice, Igwe and Stokeley remind us that archives in all forms (including archival footage) are emblems of the colonial power relations that determined which histories were documented. Their collaborative projects animate archival footage to create fictive spaces for their ancestors, exploring the potential for autobiography and fictional archives to disrupt the linear timelines and racist hierarchies of Western history and historiography. Their autoethnographic performances repurpose, reimagine and juxtapose archival images from Jamaica and Nigeria to situate the concept of “hiraeth”—a “longing or nostalgia for a home you cannot return to because it no longer exists or never existed”—in the context of the black diaspora.

Renee Drouin considers archival temporalities and queer identity through video gaming and its construction of characters. In “Games of Archiving Queerly: Artefact Collection and Defining Queer Romance in Gone Home and Life is Strange”, Drouin argues that the possibility of representing queer identities is linked to archival collection practices in video games with two queer women characters who, Drouin asserts, engage with Ann Cvetkovich’s archive of trauma. In these two games, some queer characters can only be known through their archives (some of which assume the form of diary entries), heightening the stakes for the collectible and archivable evidence of their existence. That evidence of queer existence, however, can be complicated by the temporalities of ephemeral voiceovers in Gone Home (2013) and can be erased entirely by the time travel logics in Life is Strange (2015).

Two articles on experimental film by Laura Stamm and Jules O’Dwyer pursue the questions related to autoethnography and childhood raised by Igwe and Stokeley and Drouin, through an examination of queer historiography in the work of Matthew Mishory and Vincent Dieutre. Their focus on autobiography, self-curation and queer childhood resonates with Lucas Hilderbrand’s expansive understanding of queer, which “not only means nonnormative or nonlinear (i.e., nonstraight) but also fabulous in both its stylishness and its deployment of fantasy and self-invention” (301–2).

In “Delphinium’s Portrait of Queer History: Rethinking Derek Jarman’s Legacy”, Stamm considers the BFI retrospective and online portal that frame the work of Derek Jarman, a figure that orients her exploration of Matthew Mishory’s twelve-minute film. She counters canonical readings of Jarman as a visionary artist whose film paintings stand out against the backdrop of New Queer Cinema, ultimately arguing that Jarman’s films cannot be taught outside of what she refers to as queer mentorship, a notion, she contends, that is tied to the temporality of cinema itself. She positions Jarman at the centre of a queer genealogy and explores the ways that Mishory’s interest in queer childhood helps to construct such a genealogy.

In “Histoire(s) de l’art: Curating the Cinema of Vincent Dieutre”, Jules O’Dwyer examines the curatorial logic of French experimental filmmaker Dieutre’s work. Here again, institutional context is relevant: Dieutre’s practice of self-curation in the context of a stated desire among French art historians for art that elaborates personal experiences becomes central to O’Dwyer’s approach to the filmmaker’s feature film, Leçons de ténèbres. O’Dwyer attends to the film’s formal, auditory and visual elements as they negotiate the line between past and present and explore the relationship between queer sexuality and autofictive self-fashioning. Dieutre’s film’s critical intervention may be its “intermedial promiscuity”, which is bound up with the filmmaker’s exploration of gay sexuality.

In the next article, Travis L. Wagner turns to the materiality of videotape to reconsider queer failure. In “Reeling Backward: The Haptics of a Medium and the Queerness of Obsolescence”, Wagner argues for the queer potentialities of activist footage shot on magnetic videotape, exploring the format’s materiality, and critical responses to it, as an ambivalent embrace of queer failure. Wagner examines the potential violence inherent in the practice of “touching history” by means of an obsolete format whose queer out-of-phase character encompasses not only the visual ghosting produced by the layering of images from different moments of recording—untimely interventions in the form of queer repetition rather than a reproductive logic—but also the paradox of a temporal experience defined by the presumed immediacy associated with the video aesthetic and the desire for its permanency as a record of an important activist legacy.

Concluding this special issue, Justin Wyatt’s “The Life Cycle of Transparent: Envisioning Queer Space, Time and Business Practice” explores queer temporalities within the industrial and narratological context of portal television, using the example of Jill Soloway’s Amazon Studios series Transparent. Noting that Transparent presented one of the first opportunities for representing queerness on portal television, Wyatt argues that the show demonstrates how flexible digital television can be, particularly in the way it reimagines time and space queerly through rethinking the life cycle of characters, season and series in both narrative and industry terms.

This special issue aims to open a dialogue among established and emerging scholars who use methodological approaches that span industry and production studies, close textual readings, practice-based performance, archival analysis, and media archaeology to explore the intersections between and among queer media, queer temporalities and media temporalities. The interstices they examine are spaces of potential congruence and conflict between early and late, obsolete and emergent, and timely and untimely queer media interventions.

References

1. Atwood, Emma Katherine. “Fashionably Late: Queer Temporality and the Restoration Fop.” Comparative Drama,vol. 47, no. 1 (Spring 2013), pp. 85–111.

2. Bowles, Nellie. “A Dark Consensus about Screens and Kids Begins to Emerge in Silicon Valley.” The New York Times, 26 Oct. 2018, www.nytimes.com/2018/ 10/26/style/phones-children-silicon-valley.html

3. Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Duke UP, 2003.

4. Delphinium: A Childhood Portrait of Derek Jarman. Directed by Matthew Mishory,British Film Institute, 2014.

5. Dinshaw, Carolyn, et al. “Theorizing Queer Temporalities; A Roundtable Discussion.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 13, no. 2/3, 2007, pp. 177–95.

6. Edelman, Lee. No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive. Duke UP, 2004.

7. Freeman, Elizabeth. Time Binds: Queer Temporalities, Queer Histories. Duke UP, 2010.

8. Freud, Sigmund. “A Letter from Freud.” American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 107, no. 10, April 1951, pp. 786–7.

9. Gone Home, PC version, The Fullbright Company, 2013.

10. Green, Erica L., Katie Benner, and Robert Pear. “‘Transgender’ Could Be Defined out of Existence under Trump Administration.” The New York Times,21 Oct. 2018. www.nytimes.com/2018/10/21/us/politics/transgender-trump-administration-sex-definition.html

11. Halberstam, J. Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke UP, 2011.

12. ---. In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives. Duke UP, 2005.

13. Hilderbrand, Lucas. “Some of This Actually Happened.” Women’s Studies Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 3/4, Fall/Winter 2015, pp. 301–6.

14. Kirby, Lynn. Parallel Tracks: The Railroad and Silent Cinema. Duke UP, 1997.

15. Leçons de ténèbres. Directed by Vincent Dieutre, Optimale, 1999.

16. Life is Strange, PS3 version, Dontnod Entertainment, 2015.

17. LogoTV. “RuPaul’s Drag Race Season 9 Teaser Trailer | Logo.” YouTube, 2 Feb. 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=g2oIIdZaIl4

18. Love, Heather. Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Harvard UP, 2009.

19. McBean, Sam. Feminism’s Queer Temporalities. London: Routledge, 2015.

20. McCallum, E. L., and Mikko Tukhanen. “Introduction. Becoming Unbecoming: Untimely Mediations.” Queer Times, Queer Becomings, edited by E. L. McCallum and Mikko Tukhanen, SUNY Press, 2011, 1–24.

21. Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. NYU Press, 2009.

22. @RuPaul. “Drastic Times calls for DRAGTASTIC Measures! @RuPaulsDragRace Now More Than Ever”. Twitter, 2 Feb. 2017, 12:34 p.m. twitter.com/rupaul/status/ 827253926621614080?lang=en

23. “Snatch Game.” RuPaul’s Drag Race. Series 9, episode 6, Logo TV, 28 Apr. 2017.24. Soloway, Jill, creator. Transparent. Topple, Picrow and Amazon Studios, 2014–.

25. Stockton, Kathryn Bond. The Queer Child, or Growing Sideways in the Twentieth Century. Duke UP, 2009.

26. Taylor, Jodi. Playing it Queer: Popular Music, Identity and Queer World-Making. Peter Lang, 2012.

27. Thomas, Kate. “What Time We Kiss: Michael Field’s Queer Temporalities.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 13, n0. 2/3, 2007, pp. 327–51.

28. Tichi, Cecilia. Electronic Hearth: Creating an American Television Culture. Oxford UP, 1991.

29. Velour, Sasha. Stonewall. Graduate Thesis Comic Book. Center for Cartoon Studies, 2013.

30. Wayne, Frank, creator. Match Game. Mark Goodson-Bill Todman Productions, 1962.

31. Weaver, Hilary. “Drag Race Winner Sasha Velour Is Not Done Addressing Those RuPaul Comments.” Vanity Fair, 15 Mar. 2018, www.vanityfair.com/style/2018/03/drag-race-winner-sasha-velour-addresses-rupaul-comments-at-nightgowns-show

32. Williams, Raymond. Television: Technology and Cultural Form. 1974. Routledge Classics, 2003.

Suggested Citation

Pramaggiore, M. and Kerrigan, P. (2019) 'Queer media temporalities' [Editorial], Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 16, pp. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.16.00.

Maria Pramaggiore is a Professor of Media Studies and Dean of Graduate Studies at Maynooth University in Co. Kildare, Ireland. She has published six books and forty articles on topics that span film and media studies, with a focus on gender, sexuality, and temporality. Her most recent book is Vocal Projections: Voices in Documentary (2018), coedited with Anabelle Honess Roe. She is currently at work on two monographs: Empathy and Transcendence: Horses in/as Cinema and Sharon Tate: American Icon.

Páraic Kerrigan is a Teaching Fellow in the School of Information and Communication Studies at University College Dublin. He was an Irish Research Council Scholar and John and Pat Hume Scholar in the Department of Media Studies at Maynooth University, where he is a Ph.D. candidate. His thesis is entitled Queering in the Years: Gay Visibility in Irish Media, 1974–2014. He has published work in Media History, The Journal of Radio and Popular Media, LGBTQS, and Media and Culture in Europe: Situated Case Studies, along with various popular press outlets such as the Irish Examiner.