Cosmopolitan Spaces of International Film Festivals: Cannes Film Festival and the French Riviera

Dorota Ostrowska

Historically, the French Riviera and the city of Cannes attracted crowds of international visitors who transformed and cultivated it into a cosmopolitan space made up of beaches, leisure, gardens, casinos and hotels. The Riviera has been vividly and polemically rendered by Jean Vigo in his experimental film À propos de Nice (1930) and, later, by Agnès Varda in her essay film and travelogue Du côté de la côte (1958). It was also the space which, in the 1920s and 1930s, attracted a diverse group of mostly Parisian artists, writers and filmmakers who moulded the space of leisure into that of cultural activity including the production and exhibition of visual arts (Silver). This development of the French Riviera into a space shaped and inhabited by cosmopolitan crowds, of cultivated public and modernist artists, is what ensured the success of the Cannes Film Festival established in 1939, at the time when the Riviera also became the destination of mass tourism. [1]

Conceived in the late 1930s, the festival was envisioned as a continuation, expansion and enhancement of the Riviera, which was a cosmopolitan and exclusive space where mass tourists were to become celebrity watchers, with the actual festival participation being guarded and limited to selected members of the global film industry (and, in the early days of Cannes, representatives of the French government and international diplomatic corps as well). In other words, the internal architecture of the festival, in terms of its public, audience and programming, was such that it mirrored the historical cosmopolitanism of the Riviera, which was highly exclusive and elitist. The cosmopolitanism of the festival, in its turn, was safeguarded by the French government, which was deeply involved in setting up, running and funding the event, seeing it as part of the French national project (Latil).

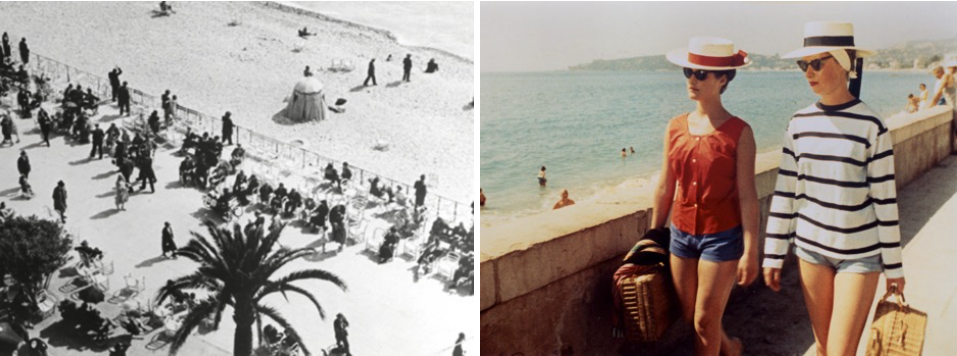

Figures 1 and 2: The pleasures of the Riviera in À propos de Nice (1930) by Jean Vigo (left)

and in Du côté de la côte (1958) by Agnès Varda (right). Screenshots.

Vanessa Schwartz described the Cannes Film Festival as a cosmopolitan vehicle for the French cinema after the Second World War, which determined much of the dynamics of the festival itself. For Schwartz, the Cannes Film Festival:

embodied an international culture in which nations, including the United States, coexisted, cooperated, and coproduced. It became crossroads of the film production community, making possible the international coproductions that came to characterize the cosmopolitan film culture of the mid-1950s to mid-1960s. (14)

Schwartz also noted the importance of some key elements which contributed to the festival’s success. Among them, she identified “the association of France and the Riviera with cultural cosmopolitanism”, and argued that both “visitors [to the festival] and the press brought a host of associations and expectations with them to the South of France and this played an important role in the construction and reception of the event” (57, 67).

In this article, I focus on these cosmopolitan attributes of the Riviera and Cannes, which contributed to the success of the Cannes Film Festival. I argue that the origins of the festival as a cosmopolitan event are found in the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century cultural history of the French Riviera. I suggest that the Cannes Film Festival mirrors and replicates the dynamics and tensions inherent in the space it inhabits—that of the French Riviera—and, thus, it is not only rooted in the Riviera’s culture, but it is also a continuation of its long history, and a fascinating extension of the myth and phenomenon of the Riviera.

In the debates around cosmopolitanism and art festivals, including film festivals, the issue of place is singled out as an important one for “festivals must be rooted in either a place or a theme” (Chalcraft et al. 112). At the same time, more often than not festivals are also seen “in terms of what Augé (1993) terms non-places: standardised, empty spaces, characterised by a lack of those relational, historical connections concerned with identity that make a place” (Chalcraft et al. 112). Proponents of cultural cosmopolitanism such as Jasper Chalcraft, Gerard Delanty and Monica Sassatelli, however, do not see these two aspects of a festival—its association with a place while displaying characteristics of a non-place—as being in conflict or offsetting each other. Rather, they argue that the crux of the matter is “in how a strong focus on the city hosting the festival—on its specificity and ‘sense of place’—combines with an intense encounter with outside artists, cultures and even publics” (Chalcraft et al. 112). In their view, cosmopolitanism, in relation to festivals, operates in such a way that “local and global need not anymore be in contrast—or ‘placedness’ and ‘placelessness’” (113). For them, “place can draw its specificity from certain types of relationships with the external or Other—what we would call cosmopolitan relationships. If it is local, it is certainly not so at the expense of the ‘global’ (rather, it is precisely because of it)” (114).

A film or art festival can therefore simultaneously hold both identities, as a place and a non-place, as an expression of its cosmopolitan condition. The question this article aims to tackle is whether, in the period before the introduction of the Cannes Film Festival, the French Riviera itself was already established as an expression of cosmopolitanism characterised by the coexistence of placelessness and placedness. I argue that, in order to draw and investigate possible comparisons between the French Riviera and the Cannes Film Festival, we first need to see the former—with its seasonal elitist tourism, parties, international jet set, hotels, casinos, gardens, beaches and the rest of its mythical ambiance—as a kind of a festival itself, much the way Varda does in her essay film. In this regard, the objective of this article is precisely to show how the “festivalised space” of the French Riviera in the 1920s and 1930s held the features of both a place and a non-place and, thus, could be considered as an expression of the cosmopolitanism commonly associated with art festivals. Itself a festivalised space displaying the particular interplay between place and non-place, the phenomenon of the French Riviera may be said to generate and to be reflected in the cosmopolitan dynamics of the Cannes Film Festival.

The notion of cosmopolitanism I embrace in this article is most closely related to the idea of cosmopolitanism as transnational movements whose main exponents are Ulf Hannerz and James Clifford, as well as Marc Augé through his writings on place and non-place (Delanty). The key characteristic of this type of cosmopolitanism is its focus on mobility and travel and the ways in which they dissolve traditional notions of place, creating new sets of relational identities along the way. It is Clifford’s metaphor of a hotel employed to express this kind of cosmopolitanism which resonates most strongly with my argument. The notion of “hotel chronotope” is, according to Clifford, an invitation “to rethink cultures as sites of dwelling and travel, to take travel knowledge seriously” (“Travelling Cultures” 105; emphasis in the original). In this way “the hotel epitomises a specific way into complex histories of travelling cultures (and cultures of travel) in the late twentieth century” (105; emphasis in the original). The hotel chronotope is part and parcel of the culture of the historical Riviera, as well as that of the Cannes Film Festival, thus standing for a communicating vessel of both spaces where “a location … is an itinerary rather than a bound site—a series of encounters and translations” (Clifford, Routes 11). This article is also an attempt at proposing a new way of thinking about the spaces of festivals, which are transient and ephemeral by nature. Tom Cresswell writes that, “while conventionally figured places and the notions of roots demand thoughts and reflect assumed boundaries and traditions, non-places and routes demand new mobile ways of thinking” (44). Unearthing the connections between the French Riviera and the Cannes Film Festival is an exploration of such mobile way of thinking in the quest to articulate a more dynamic view of cosmopolitanism in relation to festivalised spaces of various kinds.

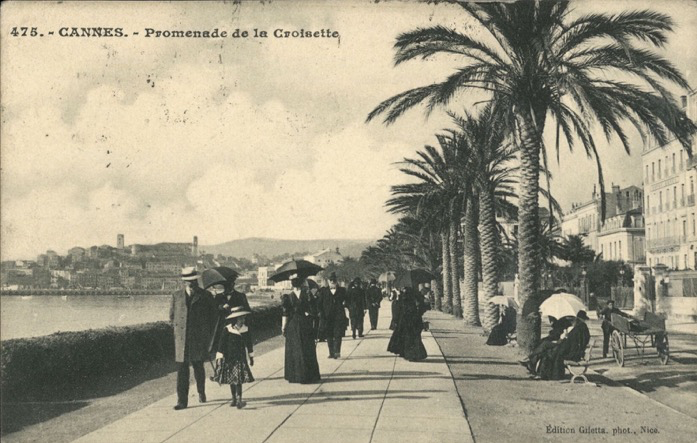

Cannes as a Cosmopolitan Non-Place: Journeying to the Riviera in the Nineteenth Century

In Marc Augé’s definition, a non-place is associated, on the one hand, with the act of passing or travelling through and, on the other hand, with words that orientate the traveller in this movement. He writes:

We could say, conversely, that the act of passing gives a particular status to place names, that the faultline resulting from the law of the other, and causing a loss of focus, is the horizon of every journey (accumulation of places, negation of place), and that the movement that “shifts lines” and traverses places is, by definition, creative of itineraries: that is, words and non-places. (85)

Journeying is generative of words, narratives and texts which become an expression and a definition of non-place. Thus created itineraries mediate between the traversing individuals and their surroundings. The connection is so close and important that certain places, Augé says, “exist only through words that evoke the places, and in this sense they are non-places, or rather imaginary places: banal utopias and clichés” (94). The history of space known today as the Riviera has been formed through the influx of French and English travellers and tourists, and through the accounts of their journeys. Such accounts are excellent examples of the mediating power of the text which, in Augé’s view, underpins the definition of non-place. The Riviera, as we know it today, did not exist in any clear geographical, historical or cultural sense before it was “discovered” by the mentioned visitors, who began going there in great numbers from the end of the eighteenth century to escape the cold winter, to find relief from the tuberculosis which was decimating the population and also on their way to Italy while on the Grand Tour. They penned a number of diaries and guidebooks which offered detailed descriptions of the landscape, nature, the sea, and also cities and towns of the region, which de facto constituted “instructions of use” to the area, to employ Augé’s phrase (96).

The region was designated as a Riviera for the first time in French and English accounts of the mid-nineteenth century. The part of the Mediterranean coast extending from Hyères to Genoa, and from Genoa to Spezia, or the Riviera di Ponente and Riviera di Levante, came to be known as the French Riviera and Italian Riviera respectively, with Menton being the natural border between them. The area is enclosed by the mountain ranges—the Alpes Maritimes and farther on the Apennines on one side, and the Mediterranean Sea, on the other (Macmillan xiii). Travellers, such as Hugh Macmillan, remarked on the views, the quality of sunlight, “which has a sparking crystalline lustre, as if each particle of air through which it passes were the facet of a gem” (xiii), the balmy climate of the Riviera, and the assault on the senses its nature constitutes. He experienced “the brilliant sunshine and the translucent atmosphere giving the feeling of vast aerial space” as striking in contrast to “the smoke of Marseilles and Toulon … [and] the cloudy northern skies” (xiii). The city of Cannes features firmly in these early accounts of the Riviera:

Cannes possesses a marked character of its own. Its locality is remarkably well chosen, the numerous low hills and rising grounds forming admirable sites for houses and gardens; and almost every view for its western background the range of the Esterels, whose marvellous beauty of form and colour affords a continual feast to the eye. To the natural picturesque features of the spot are added the charms of rich and abundant foliage, beautiful semi-tropical vegetation, and brightly coloured eastern-looking houses, all seen under a brilliant blue sky and bathed in sunshine that brings out every hue and form with the utmost distinctiveness. (15–16)

The development of the city of Cannes was not only connected to its natural beauty, but also to the presence of foreign inhabitants. The expat community of Cannes dates back to the journey of an Englishman, Lord Brougham, who was halted in his movement down the coast precisely in Cannes due to the plague warning. He was taken by the beauty of the bay of Cannes and decided to stay there following the death of his daughter.In his account of non-place, Augé notes the importance of speedy ways of transport, motorways, ring roads, and air routes to constitute a non-place as a space which one enters and exits only. He writes: “clearly the word ‘non-place’ designates two complementary but distinct realities: spaces formed in relation to certain ends (transport, transit, commerce, leisure), and the relations that individuals have with these spaces” (94). This is interesting in reference to the history of the Riviera, where travel was an important element of the potent mixture of exoticism and cosmopolitanism. In their accounts, foreign travellers often remarked on the importance of the roads and of the railway track that connected the Riviera from the second half of the nineteenth century, reaching Cannes in 1861, and opening to tourism all the small towns along the coast. In time, different means of travel along the coast were juxtaposed—the visitors were advised to take a coach rather than travel by train in order to take in more of the landscape and enjoy the natural beauty. In 1875, James Henry Bennet wrote that “there is not a more beautiful drive in Europe, and by rail it is entirely lost” (10). He advised his fellow travellers that “the start from Nice should be made about 12 o’clock, so as to have the south-western sun to illuminate the road all the way” (10).

Travel mattered for a variety of reasons, both practical and aesthetic. The railway links in the Côte d’Azur were crucial to the development of the very idea of the region as an entity. Not only the speed of travel played a role, but the ease of travel as well. One of the arguments used to assure that Cannes, rather than Biarritz, become the location of the new international film festival was precisely its accessibility. Not just rail travel, an established means of transportation by the mid-twentieth century, was mentioned, but also airplanes, which connected Paris, London and other destination to Nice—a gateway to the Riviera (“Idée d’un festival”). It was not only an international set but the international jet-set crowd which was to be drawn to Cannes and the pleasures of its festival.

The travellers along the Mediterranean coast emphasised the importance of the sweeping Mediterranean panoramic views. These sweeping vistas of the sea were very attractive in that they expanded the experience of the coast, and made this remote horizon part and parcel of its identity. Agnés Varda begins her Riviera travelogue with the gently undulating panoramic shots of the coast, interlaced with those of the Mediterranean Sea, overlaid with the following commentary that emphasises the amalgam of the land, sea, and sky which is the Riviera: “a roughly hewn coast, and azur, azur, azur. This is the Côte d’Azur, or the Riviera”. Such composite understanding of the region had bearing on the identity of the Cannes Film Festival, best captured in Schwartz’s argument about Cannes as a “Hollywood on the Riviera” whereby “the Festival underscore filmmaking’s link to a ‘Mediterranean climate’” (67). For this reason,

atmospheric comparisons were constantly made; it is not clear whether the movies were associated with the sun and the beach because of Hollywood or because the sun and beach embodied the glitz and glamour with which film culture had early become associated. (Schwartz 67)

Climate and topography of the Riviera, thus, directly evoked the potential of the region as a filmmaking location and as a festival space—both in close relation to each other. For this reason, the association of the sea views over the Cannes bay with the festival’s ambition to be an annual stage for the world cinema was not just a rhetorical statement, but rather a historical fact deeply embedded in the imaginary and myth of the region and of the festival event.

Figure 3: Azur, azur, azur: the Riviera inAgnès Varda’s Du côté de la côte (1958). Screenshot.

An international film festival such as Cannes offered an overview or panorama of a global film production in a given year. As Schwartz writes, “the Festival organisers sought to establish and direct world cinema from the beach of the Mediterranean and readily envisioned France as the perfect place because of its associations with both internationalism and a commitment to excellence in culture” (65–6). The emphasis was placed on the fact that the festival ought to have the ambition to give insight into what is most interesting and exciting in the contemporary global film production. André Bazin wrote that one of the reasons why one would come to Cannes is to gain this knowledge (“À propos” 430). However, when this overview of the global production was weak or not convincing, the festival organisers and their selection for the main competition were heavily criticised; the creation of the Semaine de la Critique, a sidebar of the festival programmed and organised by international critics, is one of the most captivating reactions to the disappointment with the main competition. Such view of the main competition led to the redesigning of the festival, whose architecture enjoyed the addition of a further sidebar, the Directors’ Fortnight (Ostrowska, “Inventing Arthouse”; Thévanin). The changes in the nature of the event were always to do with the galvanising power of certain pockets of the festival community—be it critics, directors or programmers. For this reason, it is important to look into the nature of the community which is formed in the non-place of the Riviera first, and then that of the festival.

Augé emphasises the solitary nature of the experience of those visiting a non-place and the relative anonymity it offers, which results in the formation of temporary identities. For Augé, “a person entering the space of non-place is relieved of his usual determinants. He becomes no more than what he does or experiences in the role of passenger, customer or driver” (101). The “contractual relations” are being formed by the “instructions of use” of the non-place (96, 101). Accordingly, many of the accounts of the Riviera include descriptions of the communities of foreigners, which were formed there for a period of few months, as well as descriptions of their activities—which were mostly concerned with leisure, parties and excursions into the countryside. There are some poignant remarks about the fragility of this community, which is seasonal and reconstitutes itself every year—often without some of the members who passed away, usually due to tuberculosis. The Riviera is not just the place of leisure, then, but also the place of death, with cemeteries being mentioned as a tourist attraction of Menton and also of Cannes. However, even death is made utopic and almost bearable with the remarks like “what’s to die more than to fall asleep among the flowers during this continuous fest of natural elements” (Liégeard 273). Jean Vigo notes the importance of cemeteries in his film À propos de Nice (1930), as does Varda in Du côté de la côte. In À propos de Nice,the images of the street carnival are juxtaposed with those of cemeteries, bringing together the entire spectrum of the extreme experiences present in the Riviera—ranging from exuberant eroticism and carnal pleasure to the postmortem marble renditions of the Riviera inhabitants dotting the cemeteries.

This community of the Riviera, characterised by the extremes of life and death, is mirrored in the community of the Cannes Film Festival, which consists of two principal groups: the audience and the stars. The audiences of the festival have been changing throughout its history. However, this does not mean that, at any stage in its history, the Cannes Film Festival became a public event. Its audience has always been carefully selected, with the general public never having been given any access to it, beyond being allowed to stargaze the red carpet and participate in beach screenings called Cinéma de la Plage. For the first two decades of its existence, the festival worked hard to replicate the traditional audience of the Riviera, consisting of the wealthy middle class and aristocrats who filled the hotels of the area in the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs was responsible for issuing invitations to the festival to all film producing countries across the world. As a result, the audience was dominated by government officials and diplomats, thus creating a very elitist and selected gathering. This type of attendees was over-represented until the rules regarding film selection and programming were changed after the events of May 1968, when the festival was suspended (Ostrowska, “Inventing Arthouse”; Thévanin). Historically, critics formed another segment of the audience, which was not as preselected and elitist as the international guests representing various countries. However, the critics also saw themselves as being forced to play a particular role imposed onto them through the rules of the festival. André Bazin, thus, compared a critic attending Cannes to a monk wearing a particular costume: a black tie, following a daily regime of film viewing and press conferences and, importantly, being engaged in the cult of the stars (“The Film Festival”).

Among the participants of the festival, it was the film stars who possessed most of the aura of the early aristocratic tourists of the Riviera. A Festival is a special place in which, as Edgar Morin argues, the stars feel most at home, but also, according to Bazin, the difference between them and the ordinary people, including critics like himself, is most palpable (Morin; Bazin, “Cannes-Festival”). Stars, however, also have an important link to the death or ghostly culture of the Riviera. While they are mostly known through cinema and their onscreen image, the festival is the place where they actually “materialised”. For Morin, “Cannes is the mystic site of the identification of the imaginary and the real” (48). It is the place where their ghostly and real selves coexist. Morin focuses on the privileged moment in the film festival context when the stars ascended the red-carpeted stairs of the Palais des Festivals in order to participate in the moment of a communion between their real and onscreen selves (50). This occured in the darkness of the cinema and in the presence of the selected few who were allowed to attend the same screening.

In the context of the film festival community, there are also those who historically lingered on the fringes of the event. These were producers who were coming to the festival in order to show their films to their international audiences and, hopefully, secure some sales. They mainly congregated in cinemas of the Rue d’Antibes, which were remote from the Croissette—the seaside boulevard of Cannes—and the Palais des Festivals, where the most important competition screenings were taking place. In the early days of the festival, the Market (Marché du Film) was a hidden space of the event. Over time, the Market grew in prominence and it is currently the biggest film convention in Europe, and one of the biggest in the world. Nonetheless, housed and thus hidden in the basement of the Palais, it remains invisible to the global media. Participation in the Market, in the same way as the participation in the festival, is regulated through a complex system of accreditations that limits the number of the festival public in a very significant manner. This exclusiveness of the festival, and elusiveness of its stars, which continues until today, is among the important legacies of the historical Riviera that contribute to its mystique and aura.

Cannes as Anthropological Place: Gardeners and Artists at the French Riviera

The view of the Riviera, and Cannes in particular, as a non-place, can be productively contrasted with the idea of this area as an anthropological place—in Augé terms—and the bearing it has on our understanding of the cosmopolitan nature of the Riviera and of the festival itself. What is important in the definition of an anthropological place for Augé is the relationship that its inhabitants have with the territory, which is partially materialised and partially mythologised. One can consider this feature of the anthropological place in relation to one of the most striking and visible legacies of the foreign, in particular, the English presence on the Riviera, which are the gardens the English planted during their stays there. These English horticulturalists were described by Bennet, one of the nineteenth-century English gardeners himself, as “the busy workers of social life chained to town duties, cares and occupations, living in an atmosphere of bricks and mortar, who have a secret passion for flowers and horticulture” (95). They had to travel to the Southern tip of France in order to create a refuge away from the industrialised and cloudy English shores.

Thus, the themes of exoticism and travel manifested themselves in unprecedented and unique ways in the garden culture of the Côte d’Azur, which included Cannes, but extended far beyond it on the Riviera. The gardens cultivated by foreigners, such as the Englishman Thomas Hanbury of Menton, were meant as repositories of exotic plants, whose cultivation was made possible by the Mediterranean climate. For this reason, the most famous gardens were the botanical ones. Their descriptions feature strongly in the nineteenth-century travel guides to the area, both French and English, which identify the gardens and the plants as one of the key attractions of the region.

What interested Thomas Hanbury, a Quaker and a tea and silk merchant who made his fortune in China, was a possibility of cultivating exotic plants in the Mediterranean climate and of creating an encyclopaedic garden much like that of Albert Kahn in Paris. Hanbury’s gardener, Ludwig Winter, is most commonly credited with introducing the palm tree to the region, commonly assumed to be indigenous to it. In À propos de Nice, Vigo shows palm trees in the Riviera, growing in flowerpots, thus emphasising their displacement from their place of origins. The exoticism of the palm tree did not stop it from becoming one of the most recognisable markers of the Riviera, the symbol of the Cannes Film Festival and the embodiment of its top prize, the Palme d’Or. For Hanbury and Winter, the Riviera not only became their adopted home, but also a projection of their dreams. According to Mazzino,

[Hanbury] projected the nostalgia of his travels onto the “natural scene”, reconstructing the manifestation of his emotions, and also a desire to reunite all the places and times into a single space according to the aspiration of universality so fully expressed in the 19th century. (63)

By planting many of the plants that were associated with tropical locations, the gardeners also reinforced the vision of the Riviera as a paradise or the Garden of Eden—a common trope in the early accounts of the Riviera. The planting of exotic gardens by the representatives of the international community on the Riviera constitutes the area as an anthropological space as understood by Augé.

Figure 4: The Mediterranean botanical garden.

The notion of a Mediterranean botanical garden as anthropological place was also reinforced by the reaction of the visitors. The visit to the gardens was to be a way of creating a new set of experiences for the visitors, which had to do not just with the plants, but also with the way in which the gardens were arranged in connection to different features—such as paths, fountains, grottoes, and curious objects like the Chinese bell in the Hanbury Gardens. These experiences were not indigenous to the local culture and nature; rather, they were entry points to the exotic worlds created on the Côte d’Azur for the pleasure of the foreigners visiting there for a holiday. Varda presents a vivid commentary on this exotic tourist experience in her Riviera travelogue, in which the sunglassed tourists “while seeking the sun, found oblivion”. “Where are they,” asks Varda, who answers: “Far away. Far from the coast? Far from everywhere. Call it exoticism.” And it is the botanical gardens that are for Varda “the most exotic of all” features to be found in the Riviera, even more exotic than the Riviera’s oriental architecture, also featured in the film.The film festival taking place in Cannes could be compared to an exotic botanical garden, where the curators and festival organisers attend to, and care for, the exotic stock, which is displayed and enjoyed by the international crowd of critics, diplomats, and industry representatives, along with some regular foreign visitors to the Riviera. The impulse behind the Cannes Film Festival was to celebrate the best of cinema produced annually by all film producing countries in the world, and represented by the country’s delegations, the more exotic the better. In the first two decades of Cannes, it was usual to see members of various delegations sporting their traditional attires, such as kimonos in the case of the Japanese. The festival was thus an exotic, colourful and international affair with the Cannes Film Festival posters featuring prominently, year after year, the motif of the national flags overlaid with some cinematic trope—a film strip or a camera—emphasising the festival’s international and internationalising dimension realised thanks to the cinema.

Much of the impulse behind the foundations of the botanical gardens on the Riviera has to do with a desire to achieve unity in diversity. It was the nineteenth-century idea which drove much of the garden design in places such as the Hanbury Gardens. The ideas around universalism were also linked with peace and a utopic vision of the world. These were amplified by the vision of the Riviera as the lost Garden of Eden, and supported by appropriate myths and stories featuring in the nineteenth century travellers’ diaries. For instance, one of them was that of Eve and the lemon blossom. Whilst leaving Paradise, Eve picked up a lemon flower. The Angel saw the theft, but allowed Eve to get away with it. Adam and Eve wandered the surface of the earth until they found the Côte d’Azur, where the woman decided to plant her lemon blossom, as the location reminded her so much of the Paradise she lost forever (Liégeard 270). The other story traced the origins of the name of the city of Cannes back to the Biblical wedding in Cana. Macmillan argued that “Cannes” connotes a particular kind of reed, which used to grow where the city is now located. It also evokes Cana, the place of the most famous wedding, and a site of the first miracle where Jesus turned water into wine in order to keep the party going (Macmillan 13). In both cases, the message was that the destiny of the city of Cannes was to be the source of joy and celebration for anyone visiting there.

The impulse behind the Cannes Film Festival was also driven by the ideas of peace and humanism celebrated in the party atmosphere. The foundation of the international film festival in Cannes was related to the ideological divisions that ripped Europe and the world apart in the run to the Second World War, and were present in the postwar era, concluding in the long period of the Cold War. One of the founding myths of the Cannes Film Festival emphasises how Cannes was a reaction to the “propagandistic mission” of Venice (Schwartz 59). The Italian film festival was boycotted by the Americans and other “freedom loving” nations, which led to the idea that another film festival of a similar kind needed to be founded, culminating in the establishment of Cannes. The first edition of the festival was brutally interrupted by the onset of the Second World War. However, even as the war was continuing, some plans were made for the festival right after the war ended. The idea of the French prestige, and the necessity to re-establish the cultural prominence of France after the war were very important to the Cannes project. It could only be done in the international location whose standing also needed to be revived after the war—the Riviera. However, these issues of French international prestige, or the French identity in relation to the European culture, mattered as much as those of universalism and peace, which were becoming very important in the context of the Cold War.

Concerns with universalism have always been part and parcel of the film festival culture and accompanied the ones in Venice and Cannes. Before its radicalisation to the right early editions of Venice film festival were inspired by universalism and pacifism following the First World War, and realised by the Fascist government (Ostrowska, “Inventing Arthouse” 18–21). Cannes was also mobilising the same set of peace dynamics in relation to the film festival on the Riviera, following the Second World War. The exhibition of films at festivals was seen as contributing to peace and understanding among the nations by the organisers. At the time of the Cold War, when the communication and exchange were ruptured between the two sides of the Iron Curtain, Cannes was an opportunity for representatives of different nations to meet. It was also a very practical and effective way to showcase productions and to trade. Much effort went into securing the presence of the Soviet Union, and their satellites from Eastern Europe in Cannes. Their presence was also a source of much tension and sometimes led to withdrawals of films and all kinds of diplomatic scandals (Ostrowska, “Three Decades”).

Is there anything cinematic about the anthropological place which the gardeners and the artists who settled on the Riviera created—the Riviera they imagined and realised through their distinct but related activities? Here, I would like to focus on the two aspects of the thus established anthropological place: grottos of the garden, and chapels created by the modernist artists on the Riviera. Both grottos and chapels prefigure the erection of cinemas in the Riviera imagined as the Garden of Eden. The Palais des Festivals is thus a heterotopic element of an heterotopic space.

Grottos were a fixed feature of the English gardens, and also appear in the Hanbury Botanical Gardens in Menton. Perhaps, the most striking example of a garden grotto, on which many of the grottos of the Riviera were modelled, is the one created by Alexander Pope in Twickenham, which he described as “camera obscura”. In turn, Sontag wrote about garden grottos in the following way:

the grotto has been a privileged place: it is an intensification, in miniature, of the whole garden-world. It is also the garden’s inversion. The essence of the garden is that it is outdoors, open, light, spacious, natural, while the grotto is the quintessence of what is indoors, hidden, dim, artificial, decorated. The grotto is, characteristically, a space that is adorned—with frescoes, painted stuccos, mosaics, or (the association with water remain paramount) shells. (102)

Traditionally, the English gardens have been associated with a presence of a grotto as unique feature. In her Heavenly Caves, Naomi Miller describes the grottos in the following way:

A relatively immutable element in the ephemeral world of the garden—a place of repose and reunion, or of solitude, seclusion and shade; a site of assemblages for learned discourse; a museum and a triclinium; a sanctuary of muses and an abode of nymphs; a locus of Enlightenment and poetic inspiration; a harbour for springs and fountains—the grotto is, above all, a metaphor of the cosmos. Variety of forms is almost as vast as variety of functions, with nature versus art as the leitmotif. (7)

Grottos required the proximity of water, which was partaking in shaping the space of the grottos with fantastic stalagmites and stalactites (8). Grottos were much loved elements of the English gardens because they were seen as spaces of respite and, most importantly, as imaginary, mysterious and sometimes even mystical spaces. The proximity of the Mediterranean Sea to the garden space of the Coast was the reason that the modern grotto—a cinema—was erected there. Miller points out that, as early as the end of the sixteenth century, a grotto “was a common element in theatrical scenery ... Like the theatre, the grotto thus became the perfect realm of fantasy, the domain of illusion” (60). We may finally come to the conclusion that there is nothing paradoxical about cinemas on the beach. Rather, the cinema on the beach, which is itself connoted as a garden, belongs to the very logic of the place.

The spectacles projected in the cinematic grotto are inspired and shaped by the sea, or the presence of water, and are connected to the myths of the sea, the sun, the beaches and the gardens. In this context, Gaston Bachelard’s idea that “the image is a plant which needs the presence of the earth and the water, of the substance and the form” gains a new meaning (4). Even though his focus is on poetic images, the general principle that any image implies a process of cultivation, watering and tending, stands. Naturally, a question appears as to the ways in which this cinematic grotto was actually a site of a spectacle. In order to answer, it is important to look into the history of visual arts on the Riviera and how their artistic activity could evoke the notion of a grotto and a spectacle.

Modernist artists from the generation of Picasso, Matisse, and Cocteau, who settled on the Riviera and spent most of their time towards the end of their careers on the Côte d’Azur, also contributed to its identity as an anthropological place. The most vocal in this respect was Cocteau, who actually reflected to some extent on the nature of his contribution to the life of the Riviera, and his motivations behind it. His relationship with the region was characterised by three main elements— decentralisation, understood as distancing from Paris as a cultural centre; focus on the artisanal side of artistic activity; and rooting the artistic activity in the Mediterranean creative tradition (Gullentops). In practical terms, it meant creating an artistic colony on the Riviera, of which he was a part, and which was to counter the forces of “progress” (Cocteau 16). He also contributed to the artistic activity of the region by building and decorating chapels, official buildings and private villas with the help of local craftsmen and tradesmen. Just like Picasso, he was very interested in the Provençal pottery traditions. Both artists worked extensively in this medium and left numerous examples of their works.

In his book Making Paradise, the art historian Kenneth Silver offers a detailed account of the activities of the modernist visual artists on the French Riviera. They were most productive in the 1920s and 1930s, with many of them residing there for extended periods of time, usually during the summer. It was during these sunbathed vacation periods that they invented the Côte d’Azur as a privileged mythical space, which Silver calls “the site of imagination” (25). Their paintings were populated with the iconic images of the Coast (bathers, palm trees, the sea, the sun, beaches, women and nudity), which in turn are connected to the ancient myths of Western civilisation originating in the Old and New Testament, but in most cases not indigenous to the region. The visual artists were not so much interested in painting local people or scenes of their daily lives. Rather, they were portraying their own lives there, and those of fellow holidaymakers. It was very obviously the stunning location, the bright sun, the summer season and the proximity of the sea which inspired the artists and was the main attraction of the place.

In his account of the presence of these artists on the Riviera, Silver points out that their activities were a kind of a blind spot in the contemporary accounts of art history. In his view, the artistic output of the artists when they were residents on the Riviera has been overlooked for at least two reasons. Firstly, the production of any art, in particular modern art, is supposed to be a solemn activity. In his view, for some critics there is a palpable tension between the seriousness which the production of art entails and the pleasure associated with the place where the artists reside. He demonstrates that there has been modern art created in the place of pleasure, but it can only happen when the artists manage to make the place their own—not just to incorporate it in their art, but to shape it and own it. They harness it in a way through their artistic activity. Secondly, there was a discomfort about the fact that these artists were overwhelmingly not residents, not even travellers, but really tourists and holidaymakers. Rather than stern critics of the emerging mass and consumerist society, they partake in the contemporary trend, which brought working classes to the South on their paid holidays. However, these artists were more than just tourists. As mass tourism really became a successful enterprise after the Second World War, many of them tried to leave a more permanent mark on the Riviera, by building and decorating chapels, as Matisse, Picasso and Cocteau did, as well as museum. [2]

Among the chapels erected in the Riviera by these artists, it is the chapel of Matisse which prefigures cinema most strongly. The cut-outs bring out the notion of editing and montage, the priest vests and other attributes of the liturgy, such as cups, settle a stage for the performance, while the carefully designed play of light and shadows, through the stained windows, evoke cinematic projection.This effort at rooting their art in the iconography of the South, which was by and large imaginary, and at preserving their legacy in the South are important in reconfirming the Côte as a valid and legitimate space for the creation of modernist art. Importantly, the creation is linked to preservation and exhibition in this particular geographical location. This link is significant because the shift from creation to exhibition coincided with the founding of the international festival in Cannes. The Riviera had been for a long time associated with the history of images and the presence of visual artists. Arguably, then, to found a film festival on the Riviera did not seem so unusual. It rather follows from the cultural processes which have been shaping this particular location for many decades.

Conclusion

The Riviera as a non-place has been most firmly established through writing symbolically in the accounts of travel and exploration of the Riviera by foreign travellers and visitors. As better roads and railways tracks were transforming the material topography of the Riviera, the writings in guidebooks and journals were moulding the collective imagination of the Riviera, creating a potent imprint of the place as cosmopolitan, transient and leisurely. Some of the visitors to the Riviera made the Coast their home and, thus, began the creation of another layer in the Riviera’s identity—that of the anthropological place—whose material expression were the botanical gardens and various traces of the activity by modernist artists who settled there.

In this regard, this article has demonstrated how different features of the Riviera as a place and a non-place are reflected in the material and imaginary architecture of the Cannes Film Festival. The question which remains to be answered is how the relationship between the Cannes Film Festival and, more broadly, the Riviera as both an anthropological non-place and an anthropological place contributes to the cultural phenomenon of the festival and, crucially, to its cosmopolitanism.

In his account of the relationship between the place and non-place, Augé notes that “what is significant in the experience of non-place is its power of attraction … to the gravitational pull of place and tradition” (118). The non-place wants to resolve itself into the place without ever being able to do so completely, and this impossibility of resolution is the actual bond between the two. Varda’s travelogue frames this dynamic bond between the two extremities of the Riviera in terms of nostalgia for the carnival. The Riviera out of season is a place imbued with nostalgia for the carnival which takes place in the summer months. The carnival and nostalgia for it are the two sides of the same coin and the currency of the Riviera’s cosmopolitan identity. The idea of the Riviera in season as a carnival for which the Riviera longs out of season resonates strongly with the Cannes Film Festival, which is seasonal, carnivalesque and nostalgic. The time out of the festival is that of the excited anticipation for another round of premiers and encounters that every new edition of the festival brings with it. Thus, the cosmopolitan aspects of the Riviera and of the Cannes Film Festival reinforce their mirroring identities in and out of season creating a unique cosmopolitan cocktail of carnival and nostalgia which is the most likely reason why the two have had such a powerful grip on the collective modernist imaginary.

Another powerful illustration of the paradox of place and non-place shared by the Riviera and its most famous festival is Clifford’s hotel chronotope, in which culture is seen as a site of both “dwelling and travel” (“Travelling Cultures” 105; emphasis in the original). The hotel chronotope webs and ebbs between place and non-place, with the fluctuations of the seasons remaining part and parcel of the nostalgic cosmopolitanism that characterises the festival and the Riviera.

Notes

[1] The first edition of the festival was planned for September 1939, but it was cancelled due to the outbreak of the Second World War. The first ever Cannes Film Festival eventually took place in 1946 (see Schwartz 59–64).

[2] Henri Matisse designed and decorated a Dominican chapel in Vence. Jean Cocteau decorated a fishermen chapel in Villefranche. Pablo Picasso was responsible for the Temple of Peace in Vallauris. The first museum dedicated only to the works of Pablo Picasso was set up in Antibes in 1966 as a result of his residency in the town.

References

1. À propos de Nice. Directed by Jean Vigo, Pathé-Natan, 1930.

2. Augé, Marc. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. Translated by John Howee, Verso, 1995.

3. Bachelard, Gaston. L’Eau et les rêves. Essai sur l’imagination de la matière. New edition, Librairie José Corti, 1947.

4. Bazin, André. “À propos de l’échec américain au Festival de Bruxelles.” L’Esprit, no. 137, Sept. 1947, pp. 428–35.

5. ---. “Cannes-Festival 47: Psychanalyse de la plage.”, L’Esprit, no. 139,Nov. 1947, pp. 773–4.

6. ---. “The Film Festival Viewed as a Religious Order.” Dekalog 3: On Film Festivals, edited by Richard Portman, Wallflower, 2009, pp. 13–19.

7. Bennet, James Henry. Winter and Spring on the Shores of the Mediterranean. J & A Churchill, 1875.

8. Chalcraft, Jasper, Gerard Delanty, and Monica Sassatelli. “Varieties of Cosmopolitanism in Art Festivals.” The Festivalization of Culture, edited by Andy Bennett, Jodie Taylor, and Ian Woodward, Ashgate, 2014, pp. 109–29.

9. Clifford, James. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century. Harvard UP, 1997.

10. ---. “Travelling Cultures.” Cultural Studies,edited by Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, and Paula Treichler, Routledge, 1992, pp. 96–116.

11. Cocteau, Jean. “Pour la Télévision. Je présente les Alpes-Maritimes.” Jean Cocteau et la Côte d’Azur, edited by David Guellentops, Éditions Non Lieu, 2011, pp. 15-23.

12. Cresswell, Tom. On the Move: Mobility in the Modern Western World. Routledge, 2006.

13. Delanty, Gerald. The Cosmopolitan Imagination: The Renewal of Critical Social Theory. Cambridge UP, 2009.14. Du côté de la côte. Directed by Agnès Varda, Argos Films, 1958.

15. Guellentops, David. “Jean Cocteau: decentralisation, poésie d’artisanat et méditerranéisme.” Jean Cocteau et la Côte d’Azur, edited by David Guellentops, Éditions Non Lieu, 2011, pp. 5-11.

16. Hannerz, Ulf. “Cosmopolitans and Locals in World Culture.” Theory, Culture and Society, vol. 7, no. 2, 1990, pp. 237–51.

17. Latil, Loredana. LeFestival de Cannes sur la Scène Internationale. Nouveau Monde Editions, 2005.

18. Liégeard, Stéphane. La Côte d’Azur. Maison Quantin, 1887.

19. Macmillan, Hugh. The Riviera. New and revised edition, J. S. Virtue & Co., 1892.

20. Mazzino, Francesca. An Earthy Paradise: The Hanbury Gardens at La Mortola. Translated by Clare Littlewood, Sagep, 1997.

21. Miller, Naomi. Heavenly Caves: Reflections on the Garden Grotto. George Allen and Unwin, 1982.

22. Morin, Edgar. The Stars. Translated by Lorraine Mortimer, U of Minnesota P, 2005.

23. Ostrowska, Dorota. “Inventing Arthouse Cinema: Film Festival Cultures and Film History.” Film Festivals: Theory, History, Method, Practice, edited by Marijke de Valck, Brendan Kredall, and Skadi Loist, Routledge, 2016, pp. 18–33.

24. ---. “Three Decades of Polish Films at the Venice and Cannes Film Festivals: The 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.” Beyond the Border: Polish Cinema in a Transnational Context edited by Ewa Mazierska and Michael Goddard, Rochester UP, 2014, pp. 77–94.

25. Schwartz, Vanessa. It’s So French! Hollywood, Paris and the Making of Cosmopolitan Film Culture. U of Chicago P, 2007.

26. Silver, Kenneth E. Making Paradise: Art, Modernity and the Myth of the French Riviera. MIT, 2001.

27. Sontag, Susan. “Grottos: Caves of Mystery and Magic.” House & Garden, vol. 155, no. 2, 1983, pp. 96–102, 156, 158.

28. Thévanin, Olivier. La S.R.F. et la Quinzaine des Réalisateurs 1968-2008: Une construction d’identités collectives. Aux lieux d’être, 2008.

29. “Idée d’un Festival”. Bibliothéque du Film, Paris, FIF 1B1 1938, Correspondence 22.09.1938–10.07.1939.

Suggested Citation

Ostrowska, D. (2017) ‘Cosmopolitan spaces of international film festivals: Cannes Film Festival and the French Riviera’, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 14, pp. 94–110. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.14.05.

Dorota Ostrowska is a Senior Lecturer in Film and Modern Media at Birkbeck, University of London. She has published widely on the history of film festivals and on Eastern European cinemas. Her publications include Reading the French New Wave: Critics, Writers and Art Cinema in France (2008) and Popular Cinemas in East Central Europe: Film Cultures and Histories (2017), coedited with Zsuzsanna Varga and Francesco Pitassio.