Encounters with Cultural Difference: Cosmopolitanism and Exoticism in Tanna (Martin Butler and Bentley Dean, 2015) and Embrace of the Serpent (Ciro Guerra, 2015)

Daniela Berghahn

From the travelogues of early cinema over ethnographic documentaries to contemporary world cinema, cinema has always played a pivotal role in mediating visions of cultural Otherness. By projecting images of faraway exotic landscapes, peoples and their traditions, cinema indulges armchair travellers to marvel at “wondrous difference” (Griffiths) and promotes intercultural exchange and cosmopolitan connectivity. Contemporary world cinema and the global film festival circuit, its prime site of exhibition, function as a new type of “contact zone”, which Mary Louise Pratt has famously theorised in the colonial context as the intercultural space of symbolic exchange and transculturation, catering for cosmopolitan cinephiles and their interest in cultural difference. Pratt defines contact zones as “social spaces where disparate cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination—like colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out across the globe today” (4). She describes the intercultural encounters occurring in the contact zone as “interactive”, as the constitution of subjects “in and by their relations to each other” (7). If we conceive of world cinema and its exhibition on the global film festival circuit (and beyond) as such a contact zone then the interactive exchange occurring in this space is, on the one hand, the expectation of metropolitan audiences to encounter a particular kind of world cinema that corresponds to their exotic fantasies of Other cultures and, on the other hand, the creation of “autoethnographic texts”, that is films made by non-Western filmmakers which “appropriate the idioms” of “metropolitan representation” (Pratt 7). Scholars including Rey Chow (173–202) and Thomas Elsaesser have productively applied Pratt’s critical framework to Fifth Generation Chinese cinema and world cinema more broadly. In fact, Elsaesser argues that autoethnography and (self-)exoticism are intricately linked:

Despite being celebrated on the film festival circuit, much of world cinema regularly courts controversy for pandering to the tastes of Western critics and audiences by representing non-Western cultures as “exotic”—with all the baggage this term entails. Nowhere is the concept’s burdensome legacy more provocatively delineated than in Ron Shapiro’s acerbic hyperbole: “To speak of the exotic … is to condone all manner of European imperialisms and colonialisms, and to deliberately condemn the so-called ‘subaltern’ to continued misery” (41). In his essay “In Defence of Exoticism”, Shapiro challenges postcolonialism’s unforgiving stance towards exoticism and contends that exoticism is not “necessarily false and evil” but has a rightful place in imaginative representation because “the imagination and political policies” need to be kept separate (42, 47).World cinema as post-national cinema prior to auteur status is always in danger of conducting a form of auto-ethnography, and promoting a sort of self-exoticization, in which the ethnic, the local or the regional expose themselves under the guise of self-expression, to the gaze of the benevolent other, with all the consequences that this entails. World cinema invariably implies the look from outside and thus conjures up the old anthropological dilemma of the participant observer being presented with the mirror of what the “native” thinks the other, the observer wants to see. (510)

Although I will pursue a different line of argument, I, too, set out to reassess and, ultimately, rehabilitate exoticism. By bringing it into dialogue with cosmopolitanism, I aim to demonstrate that exoticism in contemporary world cinema is inflected by cosmopolitan rather than colonial and imperialist sensibilities and, therefore, differs profoundly from its infamous precursors, which are premised on white supremacist assumptions about the Other that served to legitimise colonial expansion and exploitation and the subjugation of the subaltern. [1] What exoticism, understood as the spectacle of alluring alterity, has in common with cosmopolitanism is a positive, even empathetic, disposition towards the Other. [2] But, whereas exoticism depends on the maintenance of cultural boundaries lest cultural difference be preserved, cosmopolitanism has been described as a form of “cultural ambidexterity—the condition of inhabiting two [or more] distinct cultures” (Dharwadker 140). Both concepts have experienced revived scholarly interest in recent years since the dynamics of globalisation have profoundly changed the configurations of Self and Other, necessitating a critical reassessment of these partially overlapping concepts. Thanks to its greater interdisciplinary relevance and its undeniable appeal (for who would not want to be a “citizen of the world”?), cosmopolitanism has attracted significantly more scholarly attention than exoticism, a concept whose pejorative overtones have inhibited the same kind of extensive scholarly engagement.While globalisation has fundamentally transformed encounters with cultural difference, be it through the transnational flows of media and people (Appadurai) or the visceral practices of the everyday (Nava), it has also led to cultural homogenisation and hybridisation, both of which pose a threat to radical cultural difference on which the exotic is premised. The “drastic expansion of mobility, including tourism [and] immigration” has brought “the exotic … uncannily close” (Clifford, Predicament 13), effectively resulting in the “erosion of the exotic via entropic levelling” (Forsdick, “Revisiting” 53). Consequently, the exotic continues to exist merely as a discursive practice. Yet paradoxically, the more “self-other relations [become] a matter of power and rhetoric rather than essence” (Clifford, Predicament 14), the greater the desire for authentic, pure or exotic cultures that are ostensibly uncontaminated by contact, exchange and processes of cultural hybridisation.

Over the past decade or so, film festivals have responded to the cosmopolitan interest in “locally authentic” (increasingly used as a politically correct synonym for “exotic”) cultures by featuring a growing number of films about Indigenous people, imagined as uncontaminated by the forces of globalisation. [3] Tanna (Martin Butler and Bentley Dean, 2015) and Embrace of the Serpent (El abrazo de la serpiente, Ciro Guerra, 2015), two recent feature films about Indigenous people in the South Pacific and the Amazon which won prestigious prizes at the Venice and Cannes Film Festivals in 2015 and which were nominated for the Academy Awards, will serve as case studies to illustrate how the cosmopolitan and exotic imagination coalesce. [4]

Exoticism and Cosmopolitanism

There is general consensus amongst scholars that “the exotic as such does not exist” but that it is merely “the product of a process of exoticisation” (Mason 147). As Graham Huggan puts it,

the exotic is not, as is often supposed, an inherent quality to be found “in” certain people, distinctive objects, or specific places; exoticism describes, rather, a particular mode of aesthetic perception—one which renders people, objects and places strange even as it domesticates them, and which effectively manufactures otherness, even as it claims to surrender to its immanent mystery. (13)

It is therefore necessary to distinguish between “the exotic”, denoting a particular perception of cultural difference that arises from the encounter with foreign cultures, landscapes, animals and people that are either remote or taken out of their original context and inserted in a new one, and “exoticism”, denoting a representational strategy that is capable of rendering something as exotic. The word “exotic” was first introduced into the English language in 1599, meaning “alien, introduced from abroad, not indigenous”. During the nineteenth century “exotic” gained the connotation of “a stimulating or exciting difference, something with which the domestic could be (safely) spiced” (Ashcroft, Griffiths, and Tiffin 94). The literary and cultural practice of exoticism is inextricably linked to the eighteenth-century culture of exploration. However, by the time it came into its prime in the mid-nineteenth century, “the diffusion of ‘Western civilization’ to all corners of the globe” meant, as Claude Lévi-Strauss puts it, that “’humanity [was rapidly] sinking into monoculture’” (Bongie 4). Hence, in his aptly titled book Exotic Memories, Chris Bongie defines exoticism as “an ideological project” and a “discursive practice intent on recovering ‘elsewhere’ values ‘lost’ with modernization” (4–5) and rapid colonial expansion. Nevertheless, the quest for an exotic, desired elsewhere has persisted to this day. In contemporary societies, it manifests itself in the commodity fetishism of “culturally Othered goods”, regarded by Graham Huggan as “a pathology of cultural representation under late capitalism” (3).

Exoticism understood as a form of “cross-cultural commodity fetishism” (Chow 59) shares many features with the cultural practices of everyday cosmopolitanism, notably the globalisation of tastes which manifests itself in the ever-growing appeal of ethnic fusion food, New Asian cool, ethno chic, prize-winning postcolonial literature, global adventure travel, world cinema and world music. This kind of consumerist cosmopolitanism is distinct from the attitude and behaviour of genuine cosmopolitans, who display “a greater involvement with a plurality of contrasting cultures” (Hannerz 103). Genuine cosmopolitanism requires certain cultural competencies “to make one’s way into other cultures through listening, looking, intuiting and reflecting … and a built-up skill of maneuvering more or less expertly within a system of meanings” (Hannerz 103). These skills exceed those of the average tourist or mere consumer of global exotica. According to Hannerz, cosmopolitanism is “an orientation, a willingness to engage with the Other. It entails an intellectual and aesthetic openness toward divergent cultural experiences, a search for contrast rather than uniformity” (103). In this sense, the cosmopolitan “disposition or orientation towards the world and others” (Cohen and Vertovec 13) is not dissimilar from that of the ethnographer who observes, tries to interpret and understand other cultures or, indeed, the “‘exot’ … a traveller in exotic worlds, living, collecting and recording exotic difference” (Kapferer 819).

At first glance, these considerations seem to suggest that exoticism, denoting a particular mode of aesthetic perception and representation, and cosmopolitanism, referring to “an intellectual and aesthetic stance of openness toward divergent cultural experiences [and] an appreciation of cultural diversity” exhibit significant overlap, making a clear demarcation of the terms difficult (Cohen and Vertovec 13). Yet at closer inspection it transpires that cosmopolitanism is a far more polymorphous concept than exoticism. Cohen and Vertovec differentiate no less than six rubrics:

(a) a socio-cultural condition; (b) a kind of philosophy or world-view; (c) a political project towards building transnational institutions; (d) a political project for recognizing multiple identities; (e) an attitudinal or dispositional orientation; and/or (f) a mode of practice or competence. (9)

Such is the complexity of the term that scholars have felt the need to narrow it down by prefacing it with modifiers such as “discrepant” (Clifford, “Traveling Cultures”), “rooted” (Appiah, Ethics), “visceral” (Nava), “vernacular” (Werbner) and countless more. Clearly, this is not the place to trace the scholarly debates that have surrounded this proliferating concept in recent years. Instead, the primary concern of this article is to identify how exoticism and cosmopolitanism intersect in a particular type of world cinema.

Before doing so, it is however worth noting that cosmopolitanism’s empathetic engagement with cultural difference is anti-essentialist, attending to the local specificities in which cultural Otherness manifests itself, whereas exoticism tends to essentialise Otherness. In fact, the latter functions rather like a hermeneutic circuit: in order for the exotic to be recognised and deciphered as exotic, it needs to resonate with already familiar images and ideas of Otherness. Victor Segalen, one of the principal commentators on exoticism, alludes to the clichéd iconography commonly associated with exoticism when he writes: “Throw overboard everything used or rancid contained in the word exoticism. Strip it of all its cheap finery: palm tree and camel; tropical helmet; black skins and yellow sun” (18). Or, in the words of Fatimah Tobing Rony, “The exotic is always already known” (6). Glossing Claude Lévi-Strauss, she notes that “explorers, anthropologists and tourists voyage to foreign places in search of the novel, the undiscovered. What they find … is what they already knew they would find, images predigested by certain ‘platitudes and commonplaces’” (6). I shall return to Segalen and Rony’s pertinent observations when examining how Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent aestheticise and spectacularise cultural difference.

Arguably, the most significant distinction between exoticism and cosmopolitanism arises from the different ideological premises with which these concepts are customarily associated. Cosmopolitanism is closely allied to the project of European Enlightenment and, in particular, to the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, who postulated the normative ideal of a cosmopolitan order and a universal civic society in a series of essays written around the time of the French Revolution. [5] Kant’s moral cosmopolitanism is based on the premise that reason is a capacity shared by all human beings and that this universal quality makes them members of a single moral community. As equal members of such a universal brotherhood of mankind, all human beings should enjoy the same rights, freedom and equality. [6] This ethico-political imperative also informs contemporary conceptualisations of cosmopolitanism, which emphasise the need for solidarity and the obligations we have towards the distant Other (Appiah, Cosmopolitanism), the respect for human dignity and diversity (Skrbiš and Woodward) and a commitment to promote universal equality amongst all world citizens.

Evidently, the moral precepts of cosmopolitanism are incompatible with ideologies that promote racial difference as a justification for hierarchies of power, such as slavery and colonial exploitation. It is here where exoticism—at least in its old colonial and imperialist forms—and cosmopolitanism fundamentally differ. For centuries, exotic spectacle “and the curiosity it arouses” has served as “a decoy to disguise” inequities of power between the West and its Others (Huggan 14). Although contemporary exotic cinema has not entirely succeeded in diffusing its colonial legacy, it has nevertheless come a long way in dissociating itself from the tainted discourses of colonialism and imperialism with which it has been entwined by aligning itself with various cosmopolitan agendas, as the analysis of the two case studies will show.

The Convergence of Cosmopolitan and Exotic Sensibilities in Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent

In the broadest sense, cosmopolitan and exotic cinema refer to films concerned with crosscultural encounters and the negotiation or crossing of cultural boundaries. Whereas exotic cinema articulates a particular mode of aesthetic perception of Other cultures that is anchored in specific textual strategies, the same does not apply to cosmopolitan cinema. According to Celestino Deleyto, cosmopolitan cinema is concerned with “border thinking [which] structures filmic narratives [and] our thoughts … of being in the world” (6). [7] However, the centrality of border thinking neither manifests itself in distinctive “formal correlatives in movies” nor in “specific cosmopolitan cinematic forms” (Deleyto 6). Pursuing a similar argument, Felicia Chan asserts that cosmopolitan cinema “gives voice to the experience of border crossing, often by crossing multiple borders” (5), be they national, linguistic or cultural borders within the film’s diegesis or the borders which transnational cinema traverses on its circuits of distribution, exhibition and reception. Rather than grounding cosmopolitan cinema in a distinctive aesthetics, Chan suggests that it is a type of cinema that “enables us to talk and think of cosmopolitanism as a critical mode of understanding cultural practices and relations” (6). Maria Rovisco, by contrast, tries to pin the elusive concept of cosmopolitan cinema down by defining it as “a cross-cultural practice [and] a mode of production” characterised by “particular aesthetic and ethico-political underpinnings” that has arisen in the contemporary context of multi-directional global mobilities and border crossings (149). Indebted to Anthony Kwame Appiah’s notion of cosmopolitanism as a moral obligation towards the perils of the distant Other, with whom we share neither kinship nor citizenship (Cosmopolitanism xiii), [8] Rovisco proposes that cosmopolitan cinema aims to “increase sensitivity, inspire a debate and further understanding of distant others, and move beyond compassion” by inviting “solidarity with the plight of others” (152, 153). [9] She takes further cues from Appiah, who argues that cosmopolitan ethics takes seriously “the value not just of human life but of particular human lives, which means taking an interest in the practices and beliefs that lend them significance. People are different, the cosmopolitan knows, and there is much to learn from our differences” (Cosmopolitanism xiii). According to Rovisco, cosmopolitan cinema facilitates the process of learning from our differences by giving “voice to ‘others’ whose access to cultural dialogue is severely limited” (149). What this means in concrete terms is that those communities hitherto silenced, marginalised or excluded altogether from (self-)representation are empowered by becoming active collaborators in the construction of their own images. Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent are apt examples of how the cosmopolitan mode of production, in combination with overtly exoticist modes of representation (which I shall explore below), promotes cosmopolitan connectivity. Drawing on Rey Chow’s observation that much of contemporary world cinema uses exotic spectacle as a form of attractive, glossy packaging in order to contend “for attention in metropolitan markets” (58), I conceive of the exoticism of Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent as a vehicle to capture metropolitan audiences’ interest and to ensure that the films’ ethico-political agendas are effectively communicated.

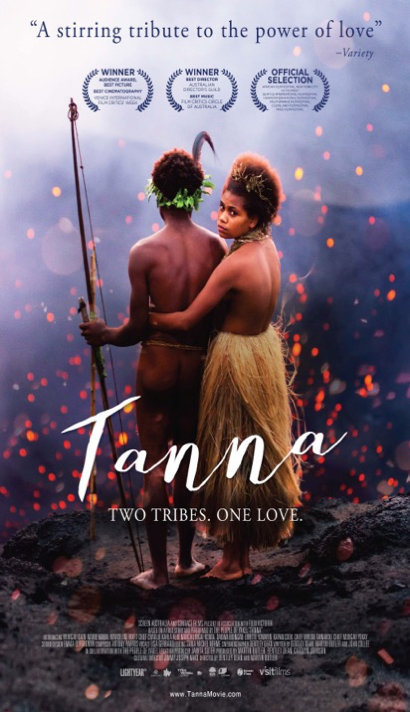

Figure 1: Poster of Tanna (Bentley Dean and Martin Butler, 2015) – Two Tribes. One Love.

Contact Films, 2015.

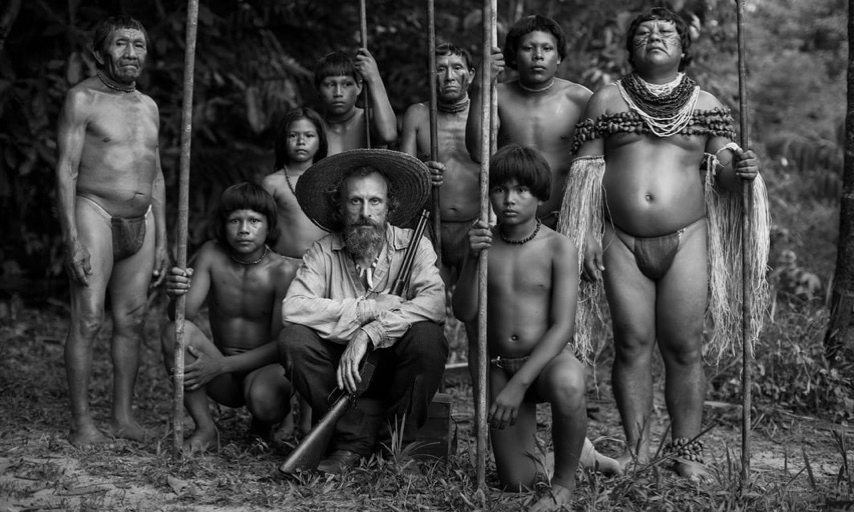

Before exploring the convergence of cosmopolitan and exotic sensibilities in the two films, it is necessary to briefly introduce them. Tanna is set on the eponymous remote South Pacific island which, as part of the Vanuatu archipelago, gained independence from French and British colonial rule as late as 1980. Tanna’s iconography of lush tropical forests, gushing waterfalls and Indigenous tribes clad merely in grass skirts and penis sheaths, though reminiscent of ethnographic documentaries, is actually a fiction film. The film’s narrative was inspired by a song Martin Butler and Bentley Dean, two Australian filmmakers who made a number of award-winning documentaries about Australia’s Aboriginal history together, heard on Tanna Island when researching another documentary. Together with John Collee, whose scripts include mainstream films like Master and Commander (Peter Weir, 2003)and Happy Feet (George Miller, 2006), and “in collaboration with the Yakel people” (Tanna Press Kit), they developed the script. The plot revolves around Wawa (Marie Wawa), a young girl from the Yakel tribe, who falls in love with the chief’s grandson, Dain (Mungau Dain). When an intertribal dispute escalates, Wawa is promised in marriage to a man from the Imedin tribe as part of a peace deal. Dain and Wawa reject the custom of arranged marriage and elope together. The only place where the star-crossed lovers can find refuge is with an Indigenous Christian community, presented as a monstrous form of cultural hybridity and, therefore, no alternative for Dain and Wawa. But with nowhere to go on the small island, they eventually poison themselves with mushrooms and die together in eternal embrace on top of the island’s roaring volcano.Like Tanna, Embrace of the Serpent by the Colombian director Ciro Guerra has the look and feel of an ethnographic documentary, not least because its monochrome cinematography recalls the daguerreotype photographic plates of the Amazon and its Indigenous people taken by early twentieth-century explorers who inspired the film. The narrative is loosely based on the travel journals of two scientists, the German ethnographer Theodor Koch-Grünberg (called Theo in the film and played by Jan Bijvoet) and the American ethnobotanist Richard Evans Schultes (Evan, played by Brionne Davis), who travelled through the Amazon during the first half of the twentieth century. In the film’s fictionalised account of these journeys, they are both looking for the sacred Yakruna plant. Theo, who is weakened by a tropical disease, hopes the flower’s healing properties will save his life. Evan, ostensibly interested in the plant’s hallucinogenic effect, is actually looking for a disease-resistant rubber tree which the United States badly needed for the war effort. Yet rather than placing these Western ethnographers at the film’s narrative centre, Embrace of the Serpent tells the story from the perspective of the Amazonian shaman Karamakate (meaning “the one who tries”), whose young and old selves are played by two different actors (Nilbio Torres and Antonio Bolivar, respectively). Karamakate’s muscular body, covered merely by a loincloth and a majestic necklace, and his dignified poise evoke the iconography of the Noble Savage. This last survivor of the Cohiuano tribe, however, lacks the innocence and utopian promise associated with this archetypal figure since contact with Western civilisation has made him a profoundly conflicted character, angry and mistrustful of foreign intruders. Nevertheless, the young and old Karamakate agree to escort Theo and later Evan up the Amazon River in a wooden canoe. The two journeys, set more than thirty years apart, convey in time-lapse fashion the increasing devastation Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors, Roman Catholic missionaries and rapacious Columbian rubber barons have wrought on the Amazonian wilderness, having shown neither respect for the natural resources nor for the traditions and beliefs of the Indigenous people whom they converted to Christianity (portrayed as a grotesque form of creolisation like in Tanna), enslaved and worked to death on the rubber plantations.

Figure 2: Theo (Jan Bijvoet) amongst Amazonian Indians in Embrace of the Serpent (Ciro Guerra, 2015).

Courtesy of © Peccadillo Pictures.

Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent, two films that were recently “discovered” and celebrated on the global festival circuit, deftly illustrate Bill Nichols’s evocative description of film festivals as a new type of contact zone where cosmopolitan cinephiles can enjoy “an abiding pleasure in the recognition of [cultural] differences” (Nichols 16, 18). Nichols compares the festivalgoer’s experience with that of an anthropological fieldworker, who becomes submerged “in an experience of difference, entering strange worlds, hearing unfamiliar languages, witnessing unusual styles” (17). While these observations confirm that there is indeed a close affinity between exotic and cosmopolitan sensibilities, a detailed analysis of how these sensibilities manifest themselves in a particular cinematic text and its mode of production is still outstanding.

The genesis of Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent encapsulates the crosscultural collaborative filmmaking practices Rovisco regards as a hallmark of cosmopolitan cinema. The promotional material surrounding Tanna’s release suggests that the codirectors and coproducers, Butler and Dean, were merely the facilitators, who enabled the Yakel tribe to bring their own story on to the screen and, eventually, to the attention of international film festival audiences. Martin Butler’s statement in the film’s press kit describes the making of the film as a truly cosmopolitan encounter that matches Ulf Hannerz’s characterisation of genuine cosmopolitanism, cited above:

For seven months we lived together [with the Yakel tribe], exchanging food, stories, ceremonies, laughter, pain and adventures. Bentley’s children played with theirs, learning their language and way of life.

One day the men sung a deeply moving song about two lovers who dared defy the ancient laws of arranged marriage, some 20 years earlier. They said the young lovers’ story changed the course of Kastom [traditional system of laws, beliefs, songs and social structures] on the island.

Tanna is a cinematic translation of that song—which is at its heart a story of the universally transformative power of love. (Tanna Press Kit)

Rather than claiming creative ownership, Butler and Dean assume the role of cultural translators, who possess the equipment, technological know-how and cultural competencies to translate Indigenous culture and oral history into the cinematic style and language global audiences are accustomed to, albeit without sacrificing its authenticity. [10] When I approached Butler and Dean in 2016, requesting an interview with them, they adopted the same self-effacing stance and suggested that I interview J. J. Nako, the film’s cultural director and a member of the Yakel tribe, instead.The emphasis on shared creative ownership in the film’s publicity campaign is particularly salient in the context of Indigenous cinema which is inextricably linked to a sense of colonial guilt. The cosmopolitan sensibilities of the contemporary moment demand a heightened sensitivity to a long history of colonial violence and exploitation and the need for atonement. For a white majority culture filmmaker to appropriate an Indigenous story, therefore, creates a sense of unease and raises serious ethical questions, as testified for example by the debates surrounding the globally successful film Whale Rider (Niki Caro, 2002), which is based on a Māori story but filmed by Niki Caro, a Pākehā filmmaker (Joyce). [11] Indigenous self-representation, the alternative approach, is, as some critics have argued, not necessarily “a solution to the problem of cultural exploitation” (Davis 6) on account of its inherent ethnocentrism and essentialism (Fee). Advocates of crosscultural collaborative filmmaking perceive genuine intercultural dialogue and co-operation not only as an ethically sound middle way but as the only way. They argue that the radically different storytelling traditions of Indigenous communities make their narratives (and, by implication, films based on Indigenous oral history) inaccessible to metropolitan audiences (Davis).

In an extended interview with Cineaste, Ciro Guerra also highlights the need for cultural translation and close collaboration. When he started working together with the Amazonian Indians, he realised that the “anthropologically accurate film” which he had originally planned to make had to be “contaminated with Amazonian myth” in order to make the film “feel more like an Indian tale” (Guillén). But then he worried that “the film would become incomprehensible for an audience [as] it’s such a different way of storytelling” (Guillén). One example Guerra discusses is the different temporality that shapes the experience of the Amazonian Indigenous people: “Time to them is not a line, as we see it in the West, but a series of multiple universes happening simultaneously” (Embrace Press Kit). In order to convey this alternative sense of time, “we translated the script together with them. And during the process of translation, they rewrote the script. They put a lot into it. They made it their own” (qtd. in Prasch 94). This alternative sense of time is reflected in the fluid transitions between the narrative strand revolving around Theo’s and Evan’s journeys in 1909 and 1940, which convey simultaneity rather than temporal progression.

The film’s cosmopolitan orientation is further reflected in the director’s avowed intention to spark “curiosity in the viewers, a desire to learn, respect, and protect this [Indigenous] knowledge which I think is invaluable in the modern world” (Embrace Press Kit). In order to equip metropolitan audiences with a better understanding of non-Western regimes of knowledge, the press kit of Embrace of the Serpent includes a glossary of some eighteen terms, which are explained in detail; for example: “Caboclo: Name given to ‘acculturated’ natives who work for the whites. The literal translation of the word is ‘traitor’” and “Mambe: Mixture of coca leaves, minced to a fine powder, and ashes of leaves of yarumo, a plant that activates and empowers the energetic and nutritional properties of the coca leaf”. Such a glossary (a similar one can be found in the press kit of Tanna), coupled with the film’s multilingualism, is a strategy designed to create an aura of ethnographic authenticity, be it real or staged.

The concept of “staged authenticity”, originally developed by Dean MacCannell in the 1970s with reference to the social space of tourist settings, is relevant in relation to the ethnographic exoticism of both films under consideration here. MacCannell proposes that the tourist’s quest for “authentic experience” stems from “the shallowness [and] inauthenticity” of modern society, which explains the fascination with the sacred in primitive society” (589–90). Yet tourists rarely have access to what the anthropologist Erwin Goffman has described as “back region” knowledge. Instead of becoming participants, they remain outsiders for whom supposedly authentic rituals are performed or “staged”.

Ethnographic filmmaking has traditionally accommodated this desire to get a “back region” glimpse of radically different cultures. The ethnographic aesthetics of Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent, coupled with the emphasis placed on crosscultural collaboration with Indigenous people, taps into this representational tradition while at the same time catering to metropolitan audiences’ interest in local authenticity. Tanna’s aura of ethnographic verisimilitude is further reinforced by the fact that the film is based on a true tragic love story that changed marriage customs on the island (Berghahn and Nako). Moreover, like in an ethnographic documentary, the actors are performing their real selves: “The chief played the chief, the medicine man played the medicine man, the warriors played the warriors”, cultural director Nako comments (Tanna Press Kit).

Most film critics appear to have accepted the premise of authenticity on which the promotion, and arguably the success, of Tanna are based. Reviewers have lauded the film for its “captivating simplicity” (Rooney) and its “consummate visual achievement”, the untrained cast’s “magnetic” performances and its “warm, shimmering vitality” (Buckmaster). Surprisingly, nobody has raised any objections to Tanna’s overtly exoticist representation. Even when Nako and the lead actors, Mungau Dain and Marie Wawa, attended the Venice Film Festival in 2015 in their traditional tribal attire, nobody suggested that the cast and crew were merely staging an exotic fantasy to please global festival audiences. The film’s positive reception stands in stark contrast to the pejorative comments exoticism, even in its postcolonial decentred forms, customarily incurs.

Salman Rushdie provides a plausible explanation for the critics’ surprising leniency vis à vis Tanna’s overt exoticism by identifying authenticity as “the respectable child of old-fashioned exoticism” (67). While local authenticity is perceived as “good” since it gives a voice to various marginalised communities and since it is associated with various cosmopolitan, humanitarian and political causes, exoticism is “bad” due to its Eurocentric imperialist legacy. But how would our response to Tanna change if we found out that the fantasy that there is still a remote place on earth untouched by the homogenising forces of globalization, is actually a skilful invention—a form of “staged authenticity”? The film’s plot and mise-en-scène purposely construct the fiction that the Yakel people are “the last keepers of Kastom” and adhere to “the old ways of life”. For example, money does not appear to be legal tender in this precapitalist society, instead the Yakel and Imedin tribes trade with kava and pigs; when Wawa’s father is fatally wounded in an attack, he is not taken to a nearby hospital but cured by spiritual healing practices. Similarly, the Yakel people are never shown with mobile phones but use drums and a conch shell to communicate via long distances. Lamont Lindstrom, an anthropologist specialising in Melanesia who has lived on Tanna Island for many years, takes issue with the film’s “staged authenticity”:

A freelance photojournalist in the early 1970s convinced people from the community to take off their clothes to boost the appeal of his photographs. Ever since, men here (especially when paying tourists come around) sport traditional penis wrappers, and women wear bark skirts … In real life, Yakel is a popular tourist site, located only a few kilometres up the hill from Lenakel, Tanna’s main town centre … Most everyone on Tanna, young and old alike (including folks in Yakel), carries mobile telephones these days. … And those penis-wrapper-wearing Yakel men are the island’s outstanding global travellers. They have starred in a variety of reality television series that have brought them to the UK, France, USA, and Australia. … the Tannese are extremely savvy about the West’s romanticism for “ancient cultures” and cannily position themselves within the international tourism marketplace accordingly. [12]I tried to verify these allegations in an interview with the film’s cultural director. Despite wearing Western clothes during the interview, Nako asserted that the Yakel people’s dress code was entirely authentic, not a costume put on to please the tourists or film festival audiences in Venice and elsewhere. However, he confirmed that the Yakel people do, indeed, have mobile phones, as well as access to Vanuatu’s public health system, thereby undermining the myth of the tribe’s complete self-sufficiency and rejection of all modern technologies. “We need support from the Westerners, but we also need to protect our culture. Whatever protects our culture, we accept. Whatever destroys our culture, that’s what we keep away” (Berghahn and Nako). Does this revelation of partially “staged authenticity” make us feel cheated? Do we now regard Tanna as ethno kitsch or as a clever form of tourist destination marketing? The film’s cultural director does not see it this way, asserting instead that the film has given his people public visibility on a global scale, shown audiences around the world a different way of life and has even advanced a political objective, namely the recognition of the Tannese Indigenous communities and their laws of Kastom by the Vanuatu government (Berghahn and Nako). In this way, the making of Tanna and its (trans)national circulation have advanced the cosmopolitan agenda of empowering a hitherto disenfranchised community.

Embrace of the Serpent is motivated by a similar cosmopolitan impetus. By making this film, the Colombian filmmaker Ciro Guerra assumes the role of custodian of Indigenous collective memory, a role that can be ascribed to cosmopolitan as well as exoticist sensibilities. The Colombian director’s intention is made explicit in the intertitles which accompany the explorers’ ethnographic photographs at the very end of the film: “This film is dedicated to all the peoples whose song we will never know”, a reference to Amazonian Indian tribes most of whom were annihilated. In an interview, the director states that the film aims to rescue “the memory of an Amazon that no longer exists” and to “create this image in the collective memory, because characters like Karamakate—this breed of wise, warrior-shamans—are now extinct. The modern native is something else, there is much knowledge that still remains, but most of it is now lost” (Embrace Press Kit).

On the one hand, the admirable endeavour to salvage the collective memory of Amazonian Indians is the kind of atonement for past collective guilt which is in keeping with the human rights regime of cosmopolitan memory politics. This kind of cosmopolitan memory, Levy and Snaider argue, derives from the “expanded global awareness of the presence of others and the equal worth of human beings” and the willingness to preserve “memories of past human rights violations” (205). On the other hand, the preservation of Indigenous collective memory is precisely the kind of salvage operation which, according to Chris Bongie, has always been one of exoticism’s primary objectives: “The project of exoticism is to salvage values and a way of life that had vanished, without hope of restoration, from post-Revolutionary society (the realm of the Same) but that might, beyond the confines of modernity, still be figured as really possible” (46). Exoticism understood as a “salvage operation [is] a revolt against the ravages of modernity” (Shapiro 46), which explains why temporal and spatial remoteness frequently coalesce in the exotic imagination. Nowhere is this more apparent than in representations of “primitive” cultures.

“Primitive” cultures, in particular, have elicited the very same instinct to salvage and recuperate in ethnographers and ethnographic filmmakers which Bongie and others have identified in relation to the exotic (Rony; Griffiths). Since primitive cultures have an antithetical relationship to modernity, they hold a particular appeal in times of crisis and disenchantment with modernity since they are imagined as “uncontaminated” by Western civilisation. However, the “primitive”, to which Rony refers as “fascinating cannibalism”, is an ambivalent concept, denoting a “mixture of fascination and horror”, whereby “cannibalism is not that of the people labelled Savages but that of the consumers of images of bodies—as well as actual bodies on display—of native peoples offered up by popular media and science” (10). If the primitive is constructed as “the pathological counterpoint to the European” (Rony 27) then it is also its utopian Other. The utopian propensities of primitivism are encapsulated in the myth of the Noble Savage, who is constructed as “authentic, macho, pure, spiritual, and an antidote to the ills of modern industrialized capitalism” (Rony 194). Yet both variants of the primitive or, to use a less loaded term, the ethnographic Other, imagine Indigenous people as “stuck in the evolutionary past” (Rony 194), that is, “closer to nature when compared to the West” (Chow 23).

Figure 3: The Yakel tribe in Tanna performing a traditional dance. Courtesy of © Lightyear Entertainment.

From today’s vantage point, shaped by a combination of postimperial guilt, an acute awareness of ecological destruction and a deep nostalgia to recuperate a world and a way of life which technological progress and global capitalism have destroyed, the ethnographic Other holds out an unadulterated utopian promise. Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent articulate this idea by reconfiguring “the primitive” as a form of active resistance and as an ecological consciousness that has the capacity to save the planet and humanity. As Theo’s Indian servant, Manduca (Miguel Dionisio Ramos), in Embrace of the Serpent puts it, “If we can’t get the whites to learn, it will be the end of us. The end of everything”. Karamakate fears it may be too late already but hopes he might be wrong. This remark is one of the many interesting inversions of the civilising mission, which is an integral part of the old imperial exotic. The new exoticism, by contrast, challenges these long-established hierarchies of knowledge and power insofar as it encompasses forms of reciprocity and inversion.

Constructing and Reversing the Exotic Gaze in Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent

In what follows I will examine, first, how the aesthetic strategies of Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent construct the island of Tanna and the Amazon rainforest and its native inhabitants as exotic and, second, how the processes of reciprocity and inversion dramatised in the two films align the visual pleasure exotic spectacle affords with cosmopolitan sensibilities. As already indicated above, exotic texts build on an intertextual system of already familiar reference points that make them legible as exotic. Brown-skinned, bare-breasted women in grass skirts and men covering their nudity with nambas (Tanna) or loin cloths (Embrace) have been an integral part of ethnographic exoticism since the middle of the seventeenth century when the Dutch painter Albert Eckhout travelled to Brazil where he painted native Indians and “established a tradition for representing native identities [and an] iconography of savagery” characterised by “nudity, spears, decorative feathers [and] animated dancing” (Griffiths xix). Karamakate in Embrace of the Serpent stands in this iconographic tradition, but, as noted above, complicates the myth of the Noble Savage since he has witnessed “The horror!” (to cite Kurtz’s dying words in Heart of Darkness) which “civilisation” has brought to the Amazon, rendering him a profoundly conflicted and disillusioned man. Intertextual references to Heart of Darkness, Joseph Conrad’s paradigmatic text about the transformative power of crosscultural encounters in the deep African jungle, abound and have been noted in numerous film reviews. Other obvious exotic antecedents regularly cited by critics are The Mission (Roland Joffé, 1986) and Werner Herzog’s Amazonian adventure films Aguirre, the Wrath of God (Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes, 1972) and Fitzcarraldo (1982). In fact, the scene in which Evan plays Joseph Haydn’s “The Creation” on his gramophone and Karamakte listens appreciatively, is reminiscent of a scene in which Fitzcarraldo (Klaus Kinski) plays Caruso on top of the steamer in the middle of the jungle. Such correspondences notwithstanding, a comparison between Herzog’s and Guerra’s Amazonian adventure dramas provides interesting insights into the changing representational strategies of exoticism. The reification of Amazonian Indians, who are reduced to deindividualised and largely hostile inhabitants of an impenetrable jungle, coupled with the predominance of German in Herzog’s films, stand in stark contrast to the nine different languages spoken (including Indigenous languages such as Tikuna, Bubeo and Huitoto) in Guerra’s film and the overall attention to ethnographic detail. Whereas in the 1970s and 1980s Herzog’s construction of Amazonia satisfied audience expectations, in the twenty-first century, when global eco- and adventure tourism has made the Amazon an accessible destination, a higher degree of authenticity has become de rigueur, at least in arthouse cinema.

Both the Amazon and the South Sea islands are mythic landscapes, steeped in a long history of Eurocentric imaginative projections that instantly identifies the films’ topographies and their inhabitants as exotic (Slater; Connell; Dixon). [13] Ever since Bougainville and other European explorers travelled to Polynesia and perceived the islanders as the incarnation of Rousseau’s ideal of the natural man, untouched by the corrupting influence of Western civilisation, ever since Victor Segalen jotted down his reflections in Essay on Exoticism, the South Pacific islands have come to epitomise paradise on earth, “[a]n escape from the contemptible and petty present. The elsewheres and the bygone days” (24). Tanna’s exoticism inscribes itself in the enduring legacy of this imaginary and, in particular, the South Sea film genre which emerged in the late 1920s with Robert Flaherty’s Moana (1926). Although most critics have dubbed it a “Romeo and Juliet” story set in the South Pacific, in terms of its iconography and, indeed, narrative conceit of star-crossed lovers, Tanna betrays far more conspicuous similarities with Friedrich W. Murnau’s Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (1931). In fact, Butler and Dean initially considered giving their film the title Taboo (Dunks 29). Dain’s crown of fern fronds and Wawa’s garland of leaves recall the almost identical natural attire of Matahi (Matahi) and Reri (Anne Chevalier) in Tabu and are a staple of visual representations of the South Pacific. Tannese children and the star-crossed lovers frolicking amid ferns and fronds and a native heralding a call to all villagers on conch shell are further references to what can be regarded as the cinematic Urtext of the South Sea genre.

Figure 4: Wawa (Marie Wawa) and Dain (Mungau Dain) wearing a garland of leaves and a fern crown in Tanna. Courtesy of © Lightyear Entertainment.

While these cinematic precursors lend Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent their exotic credentials, the spectacle of pristine nature is arguably the films’ main attraction for contemporary audiences. Shots of luxuriant tropical forests with a variety of ferns, palm trees (both traditionally part of the iconography of the exotic) and a myriad of other plants convey the idea of natural abundance. The absence of roads, electricity cables or telephone masts suggests that on the remote island of Tanna time has stood still. Placing the islanders within nature but outside history is another topos of the exotic imagination. The sounds of wilderness, birdsong, cicadas, gushing waterfalls and a rumbling volcano hurling fiery lava into the sky and the growl of a Jaguar allow metropolitan audiences to immerse themselves in soundscapes they could hardly experience at home. Panoramic vistas of breath-taking natural beauty and the extended aerial shot at the end of Embrace of the Serpent, which first races upwards and then glides contemplatively over the vast expanse of the meandering Amazon River and the immensity of the rainforest, elicit visual pleasure.

Figure 5: The natural wonders of the Amazon River in Embrace of the Serpent. Courtesy of © Peccadillo Pictures.

At the same time, Embrace of the Serpent taps into the popular image of Amazonia as “a storehouse of natural wonders, one that the ‘global community’ must protect to avoid widescale environmental calamity” (Viatori 117). Such environmental concerns have also been linked to cosmopolitanism, namely the need for tackling the “global challenges [of] sharing our planet (global warming, biodiversity and ecosystem losses, water deficits)” (Held 170). Yet, once again, the affinities between cosmopolitan and exotic sensibilities become apparent when we consider the film’s ecological agenda in relation to Renato Rosaldo’s concept of “imperialist nostalgia”, a particular mode of exoticism: “Imperialist nostalgia revolves around a paradox”; just like colonisers mourned the disappearance of the cultures they have transformed or even destroyed, nowadays “people destroy their environment, and then they worship nature” (Rosaldo 69–70). Especially representations of the unspoilt wilderness and of “putatively savage static societies” (Rosaldo 70) speak to this longing for stability in a world of rapid change and hypermobility. Embrace of the Serpent spectacularises the sublime Amazon landscape to celebrate its splendour while at the same time conjuring up apocalyptic visions of an ecological cataclysm. Cast as nature’s (potential) saviour, Karamakate possesses the mythical knowledge of how to live in harmony with nature, but in order to avert environmental destruction and species extinction, he has to communicate his knowledge to the white man.

Although the shaman’s ominous warnings (“The jungle is fragile and if you attack her, she strikes back” and “You bring hell and death to Earth”) articulate the film’s conservationist agenda explicitly, more importantly, Ciro Guerra and the director of photography David Gallego rely on the alluring power of exotic images and their immanent mystery to convey this idea. Several of the film’s most captivating scenes are highly evocative yet their symbolic meaning remains ultimately opaque, or rather, mysterious in the sense of resisting rational explanation. Embrace of the Serpent illuminates this distinctive feature of exoticism by creating fluid transitions between mimetic realism and an alternative, oneiric reality that reflects the myths and spiritual beliefs of the Amazonian Indians. Enigmatic dreamlike sequences convey the shaman’s view of the natural world, a world animated by ancestral spirits and governed by laws only he understands. Yet what are spectators who are not conversant with Indigenous myths to make of the image of the serpent that devours its young ones in the film’s opening sequence? What does the serpent’s embrace referenced in the film title signify? [14] Is it the Amazon itself which, according to Amazonian mythology, was created when “extraterrestial beings descended from the Milky Way … on a gigantic anaconda snake” which then became the river Amazon (Guillén)? Or is it Theo, to whom the disillusioned Karamakate says “You are the serpent” (possibly a reference to the serpent in the Garden of Eden), shortly before a prowling jaguar (perhaps the shape-shifting shaman himself), previously identified as the harbinger of Theo’s immanent death, devours the serpent? When, in the film’s final sequence, Karamakate offers Evan caapi made from the last surviving Yakruna flower (in order to impart his ecological consciousness to the white man so that he can save the planet), he explains that this is “the embrace of the serpent”, his gift to him. Equally arresting is the haunting image of young Karamakate’s eyes being transformed into two brilliant white glowing orbits and his open mouth into a dazzlingly bright star, before the camera cuts to an infinite firmament of stars. By blurring the boundaries between myth and reality, Embrace of the Serpent transports its viewers into a dreamlike world of mystery and cosmic wonder, where the limitations of Western routines of cognition and scientific knowledge become apparent.

This is not the only way, however, in which Embrace of the Serpent, as well as Tanna, challenge the presumed superiority of Western epistemes and evolutionary progress on which older forms of exoticism are based. Instead, the films’ decentred perspective “encompasses the potential reflexivity or reciprocity within exoticism”, which according to Charles Forsdick (2001: 14), is an integral part of exoticism but one all too easily overlooked by its critics. For example, both films tackle the notion of Indigenous peoples’ presumed backwardness head-on. Tanna reconfigures it as a form of deliberate resistance when Chief Charlie says: “We have always fought to keep Kastom strong. The colonial powers, we have resisted. The Christians—we resisted. The lure of money—we resisted that also. We are the last keepers of Kastom and we are few.” Embrace of the Serpent reflects a similar disdain for the values of capitalism by showing that the heavy suitcases and boxes full of objects, which the ethnographers have brought to the Amazon, are nothing but a useless burden. As Deborah Shaw notes, “there is no superior white saviour here, only white men who must be humbled, corrected and taught how to see and recognize the flaws in their culture and the strengths in the culture of the Amazonian people”. Admittedly, this kind of cultural critique has its own exotic appeal since it is precisely what metropolitan audiences and critics expect of the Other, to resist Western hegemony, to take pride in their cultural difference and to mount a critique against rampant capitalism and everything else deemed wrong with the West. The fact that the Indigenous people in these films are represented not as “being stuck in the past” but as people who have actively chosen to resist modernity, commands our respect. Conversely, Theo’s attempt to deprive the Indigenous people of the achievements of scientific knowledge, when he demands his compass back, meets with Karamakate’s harsh criticism: “You can’t deny them knowledge”.

Another example of how Embrace of the Serpent reverses the exotic gaze is the scene in which the German scientist Theo performs a Schuhplattler, a traditional dance from the Alpine region, much to the delight of the Indigenous people whom he entertains in this way. Given that “indigenous dance [is] an icon of alterity” (Griffiths 173), the dance scene self-consciously plays with exotic iconography by Othering the white European man. In a similar vein, Tanna directs the exotic gaze at the British monarchy, challenging the Eurocentric assumption that arranged marriage is symptomatic of the islanders’ backwardness, when Wawa’s father shows his daughter photos of Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip and suggests that theirs has also been an arranged marriage, and a happy one, too. [15] By projecting the practice of arranged marriage—perceived as a signifier of alterity in the West—onto British royalty, the film makes the cultural assumptions underlying the exotic gaze transparent for metropolitan audiences. The reversal of the exotic gaze draws attention to the fact that positing the Western romantic ideal of love marriage as the universal norm is misguided, by suggesting that amongst the highest echelons of British society arranged marriage is practised, too. Somewhat inconsistently, however, Tanna’s narrative trajectory does not quite carry this idea through. Rather than valorising the equality of both matrimonial practices, the film’s melodramatic conclusion and affective resonance ultimately advocate the superiority of romantic love as the basis of marriage.Embrace of the Serpent eschews the dichotomies typical of imperial exoticism by reimagining the encounters between Indians and white explorers as a mutual rapprochement and exchange. For example, an intertitle at the end of the film acknowledges the fact that Western explorers have played a crucial role in preserving Indigenous memory, stating that their travel “diaries are the only known accounts of Amazonian cultures”. In fact, Guerra regards Koch-Grünberg and Schultes, whose diaries were read by influential people, as the forefathers of an ecological movement that developed, with a strong focus on the Amazon, in the 1970s (Guillén; Slater 134).

Figure 6: Evan (Brionne Davis) and the old Karamakate (Antonio Bolivar) in Embrace of the Serpent.

Courtesy of © Peccadillo Pictures.

The reciprocity underpinning the intercultural dialogue between the white scientists and the shaman is also dramatised in numerous scenes. For instance, Evan helps the old Karamakate, who suffers from memory loss, remember aspects of his culture by showing him detailed drawings of necklaces and photographs in Theo’s travel journals. Evan and Karamakate re-enact symbolically, and thereby acknowledge, the hostilities that have for centuries divided their people. When Evan tries to stab Karamakate, the shaman admits to having killed Evan (since he sees the two men as identical, or Evan as a revenant of Theo) some fifty or a hundred years ago (a reference to the Indians’ different sense of time and their belief in shape-shifting). On the other hand, Evan and Karamakate share what they revere most in their respective cultures: Joseph Haydn’s music and the sacred Yakruna plant whose hallucinogenic powers are visualised in a mesmerising spectacle of colours that suddenly bursts onto the screen, unexpectedly disrupting the nuanced palette of shades of grey. The exchange of these gifts symbolises the reconciliation of hitherto hostile cultures.

Conclusion

In this article, I set out to re-examine and rehabilitate the contested concept of exoticism by demonstrating how fundamental shifts in the geospatial dynamics of globalisation have transformed the exotic imaginary and its ideological underpinnings in world cinema. As the close analysis of Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent has shown, the construction of Self and Other in these films avoids the binary logic of the old imperial exotic and, instead, imagines encounters with cultural difference as a reciprocal process that challenges and inverts long-established hierarchies between the West and its Others. The films harness the visual pleasure of exotic spectacle to the ethico-political agendas of cosmopolitanism. They capture the attention of global audiences through their exquisite cinematography, which spectacularises breath-taking natural beauty and the allure of alterity while at the same time promoting a diverse range of humanitarian and ecological issues: to rescue from oblivion the collective memory of Indigenous people; to empower marginalised communities; and to draw attention to the threat of environmental destruction. Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent promote crosscultural dialogue and invite metropolitan audiences to engage with cultures that are so radically different from their own that they call the presumed superiority of Western values and regimes of knowledge into question. The crosscultural collaborative mode of production, coupled with the cosmopolitan ethics articulated in these films, make Tanna and Embrace of the Serpent paradigmatic examples of a new type of exotic world cinema. In contrast to the Eurocentric perspective of the imperial gaze, the exotic gaze in these films is decentred, emanating from multiple localities. It resonates with the zeitgeist in as much as its orientation towards the Other is avowedly cosmopolitan and, thus, profoundly different from the old imperial exotic.

Acknowledgment

I presented earlier versions of this essay, entitled “The Cosmopolitan Exotic on the Film Festival Circuit”, at the NECS Conference in Potsdam on 29 July 2016 and at the Humanities and Arts Research Institute, Royal Holloway, University of London, on 20 November 2016. I should like to thank the Humanities and Arts Research Institute for awarding me a Fellowship to research this article and Exoticism in Contemporary Cinema and Culture more broadly.

Notes[1] This essay also seeks to complement the extensive body of scholarship on the relationship between exoticism and postcolonialism, see for example: Agzenay; Chow; Célestin; Forsdick (“Travelling”; “Revisiting”); Huggan; Mason; and Santaolalla.

[2] Although this essay focuses on the alluring qualities of exoticism, it is worth noting that exoticism is an ambivalent concept that oscillates between positive and negative poles. Chris Bongie distinguishes between “imperialist” and “exotic exoticism”: whereas “imperialist exoticism affirms the hegemony of modern civilisation over less developed savage territories, exoticizing exoticism privileges those very territories and their peoples, figuring them as a possible refuge from an overbearing modernity” (17). The films analysed in this article are examples of exoticising exoticism.

[3] Examples of recent high-profile films either made by or focusing on Indigenous people that won critical acclaim at international film festivals include Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (Atanarjuat, Zacharias Kunuk, 2001); Whale Rider (Niki Caro, 2002); Rabbit-Proof Fence (Phillip Noyce, 2002); Ten Canoes (Rolf de Heer and Peter Djigirr, 2006); and The Pearl Button (El botón de nácar, Patricio Guzmán, 2015).

[4]Embrace of the Serpent was the first Columbian film ever to be nominated for the Academy Awards. It won the Art Cinema Award in Cannes and several other prizes at festivals including the Rotterdam International Film Festival, the Lima Film Festival, the Mar del Plata Festival and Sundance. Tanna premiered at the Venice International Film Festival in 2015 as part of the International Critics Week and won the Audience Award and prize for Best Cinematography. It subsequently travelled the festival circuit and picked up more nominations and awards. It was shortlisted as Australia’s nomination for the Academy Awards.

[5] Kant’s essays on cosmopolitanism are “Idea for a Universal History from a Cosmopolitan Point of View (1785); “On the Common Saying ‘This May Be True in Theory But it Does Not Apply to Practice’” (1793); “Toward Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch” (1795, revised 1796); and “International Right in The Metaphysics of Morals” (1797). They are collected in Reiss.

[6] Fine and Cohen are not the only scholars to have pointed out that Kant’s cosmopolitan ideals are profoundly Eurocentric and even explicitly racist, leading them to conclude: “Kant’s views on race would not discomfort the average Nazi” (Fine and Cohen 145).

[7] Some scholars suggest that exoticism emerges in the process of transnational reception rather than being anchored in particular textual strategies which would be recognised as exotic by “native” and “foreign” audiences alike. See, for example, Sexton; Chan.

[8] Appiah continues a line of argument that can be traced back to Kant’s normative ideal which, in effect, “was no more than a recognition of the fact that ‘the peoples of the earth have entered in varying degrees into a universal community and it has developed to the point where a violation of rights in one part of the world is felt everywhere’” (Fine and Cohen 142).

[9] This premise is problematic insofar as it assigns the Other the position of a passive victim, reliant on metropolitan filmmakers to bring the suffering of the distant Other to the attention of global audiences.

[10] Felicia Chan identifies cultural translation as a key feature of cosmopolitan filmmaking, since “any cultural text that travels necessitates some form of translation, and historically the film industry has adapted a number of translative processes to reach its audiences” (9). With reference to exoticism in Chinese cinema and visual culture, both Chow and Khoo argue that exoticism itself is a form of cultural translation, in as much as it is an attempt to make that what is strange intelligible by inserting it in a new context and, effectively, domesticating it.

[11] “Pākehā” is the Māori language term for New Zealanders of European descent and, more broadly, any fair-skinned New Zealander who is not of Māori or Polynesian heritage.

[12] Connell offers an illustrative account of other “spectres of inauthenticity” and “invented traditions” on the Melanese islands (to which Tanna belongs) in the wake of the islands’ decolonisation (571–3).

[13] In his discussion of the South Sea islands, consisting of different archipelagos (Polynesia, Micronesia, Melanesia), Connell details how Melanesia, where Tanna is located, has hitherto been imagined in rather negative terms as “an area of violence, taboo and danger” and “a land out of time, the Stone Age par excellence”, whereas Polynesia and Micronesia were imagined as tropical paradise (567).

[14] Guerra offers a full explanation of the mythological references and of the film’s title in an extended interview in Cineaste (Guillén).

[15] The reference to Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip is not as far-fetched as it may seem, since the Queen and Prince Philip actually visited Tanna Island in 1974, which resulted in the development of a religious sect, The Prince Philip Movement, on the island whose followers believe that he is a divine being.

References

1. Aguirre, the Wrath of God [Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes]. Directed by Werner Herzog, Werner Herzog Filmproduktion, 1972.

2. Appadurai, Arjun. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. U of Minnesota P, 1996.

3. Appiah, Kwame Anthony. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. Penguin, 2006.

4. ---. The Ethics of Identity. Princeton UP, 2005.

5. Ashcroft, Bill, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin. Postcolonial Studies: The Key Concepts. Routledge, 1996.

6. Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner [Atanarjuat]. Directed by Zacharias Kunuk, Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, 2001.

7. Agzenay, Asma. Returning the Gaze: The Manichean Drama of Postcolonial Exoticism. Peter Lang, 2015.

8. Berghahn, Daniela, and Joseph J. Nako. Skype Interview with Joseph J. Nako. 29 July 2016.

9. Bongie, Chris. Exotic Memories: Literature, Colonialism, and the Fin de Siècle. Stanford UP, 1991.

10. Buckmaster, Luke. “Tanna Review. Volcanic South Pacific Love Story Shot Entirely in Vanuatu.” The Guardian. 5 Nov. 2015. www.theguardian.com/film/2015/nov/05/ tanna-review-volcanic-south-pacific-love-story-vanuatu.

11. Célestin, Roger. From Cannibals to Radicals: Figures and Limits of Exoticism. U of Minnesota P, 1996.

12. Chan, Felicia. Cosmopolitan Cinema: Imagining the Cross-Cultural in East Asian Film. I. B. Tauris, 2017.

13. Chow, Rey. Primitive Passions: Visuality, Sexuality, Ethnography, and Contemporary Chinese Cinema. Columbia UP, 1995.

14. Clifford, James. The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art. Harvard UP, 1988.

15. ---. “Traveling Cultures”. Cultural Studies, edited by Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson and Paula A. Treichler, Routledge, 1992, pp. 96–116.

16. Cohen, Robin, and Steven Vertovec. “Introduction: Conceiving Cosmopolitanism”, Conceiving Cosmopolitanism: Theory, Context, and Practice, edited by Robin Cohen and Steven Vertovec, Oxford UP, 2002, pp. 1–22.

17. Connell, John. “Island Dreaming: The Contemplation of Polynesian Paradise”. Journal of Historical Geography. vol. 29, no. 4, 2003, pp. 554–81.

18. Conrad, Joseph. 1899. Heart of Darkness. Ed. Robert Kimbrough, W. W. Norton & Company. 1988.

19. Davis, Therese. “Remembering Our Ancestors: Cross-Cultural Collaboration and the Mediation of Aboriginal Culture and History in Ten Canoes (Rolf de Heer, 2006).” Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 1, no.1, 2007, pp. 5–14.

20. Deleyto, Celestino. “Looking From the Border: A Cosmopolitan Approach to Contemporary Cinema.” Transnational Cinemas, vol. 8, no. 2, 2016, pp. 95–112.

21. Dharwadker, Vinay. “Diaspora and cosmopolitanism.” The Ashgate Research Companion to Cosmopolitanism, edited by Maria Rovisco and Magdalena Nowicka, Ashgate, 2011, pp. 125-44.

22. Dixon, Wheeler-Winston. Visions of Paradise: Images of Eden in the Cinema. Rutgers UP, 2006.

23. Dunks, Glen. “Isle-cross’d Lovers. Vanuatu’s Tanna and the South Pacific on Film”. Metro Magazine, no. 188, 2016, pp. 24–28.

24. Embrace of the Serpent [El abrazo de la serpiente]. Directed by Ciro Guerra, Buffalo Films, 2015.

25. The Pearl Button [El botón de nácar]. Directed by Patricio Guzmán, Atacama Productions, 2015.

26. Elsaesser, Thomas. European Cinema: Face to Face with Hollywood. Amsterdam UP, 2005.

27. Embrace of the Serpent Press Kit. 2015. press.peccapics.co.uk/Theatrical/ Embrace%20Of%20The%20Serpent/Embrace%20of%20the%20Serpent%20Press%20Notes.pdf. Accessed 2 Apr. 2017.

28. Fee, Margery. “Who Can Write as Other?” The Postcolonial Studies Reader, edited by Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin, 2nd edition, Routledge, 1995, pp. 169–71.

29. Fine, Robert, and Robin Cohen. “Four Cosmopolitan Moments.” Conceiving Cosmopolitanism: Theory, Context, and Practice, edited by Robin Cohen and Steven Vertovec, Oxford UP, 2002, pp. 137–62.

30. Forsdick, Charles. “Revisiting Exoticism: From Colonialism to Postcolonialism.” Francophone Postcolonial Studies: A Critical Introduction, edited by Charles Forsdick and David Murphy, Arnold, 2003, pp. 46–55.

31. ---. “Travelling Concepts: Postcolonial Approaches to Exoticism”. Paragraph, vol. 24, no. 3, 2001, pp. 12–29.

32. Fitzcarraldo. Directed by Werner Herzog, Werner Herzog Filmproduktion, 1982.

33. Griffiths, Alison. Wondrous Difference: Cinema, Anthropology and Turn-of-the-Century Visual Culture. Columbia UP, 2002.

34. Guillén, Michael. “Embrace of the Serpent: An interview with Ciro Guerra”. Cineaste, vol. XLI, no. 2, 2016, www.cineaste.com/spring2016/embrace-of-the-serpent-ciro-guerra/.

35. Hannerz, Ulf. Transnational Connections: Culture, People, Places. Routledge, 1996.

36. Happy Feet. Directed by George Miller, Warner Bros, 2006.

37. Haydn, Joseph. The Creation in Full Score. Dover Publications Inc., 2009.

Held, David. “Cosmopolitanism, Democracy and the Global Order”. The Ashgate Research Companion to Cosmopolitanism, edited by Maria Rovisco and Magdalena Nowicka, Ashgate, 2011, pp. 163–77.38. Huggan, Graham. The Postcolonial Exotic: Marketing the Margins. Routledge, 2001.

39. Joyce, Hester. “Out from Nowhere: Pakeha Anxieties in Ngati (Barclay, 1987), Once Were Warriors (Tamahori, 1994) and Whale Rider (Caro, 2002)”. Studies in Australasian Cinema, vol. 3, no. 3, 2009, pp. 239–50.

40. Kapferer, Bruce. “How Anthropologists Think: Configurations of the Exotic”. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 19, no. 4, 2013, pp. 813–36.

41. Khoo, Olivia. The Chinese Exotic: Modern Diasporic Femininity. Hong Kong UP, 2007.

42. Levy, Daniel, and Natan Sznaider. “Cosmopolitan Memory and Human Rights”. The Ashgate Research Companion to Cosmopolitanism, edited by Maria Rovisco and Magdalena Nowicka, Ashgate, 2011, pp. 195–209.

43. Lindstrom, Lamont. “Award-winning Film Tanna sets Romeo and Julia in the South Pacific.” The Conversation, 5 Nov. 2015. theconversation.com/award-winning-film-tanna-sets-romeo-and-juliet-in-the-south-pacific-49874.

44. MacCannell, Dean. “Staged Authenticity: Arrangements of Social Space in Tourist Settings.” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 79, no. 3, 1973, pp. 589–603.

45. Mason, Peter. Infelicities: Representations of the Exotic. John Hopkins UP, 1998.

46. Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. Directed by Peter Weir, Twentieth Century Fox, 2003.

47. The Mission. Directed by Roland Joffé, Warner Bros., 1986.

48. Moana. Directed by Robert Flaherty, Famous Players-Lasky Corporation, 1926.

49. Nava, Mica. Visceral Cosmopolitanism: Gender, Culture and the Normalisation of Difference. Berg, 2007.

50. Nichols, Bill. “Discovering Form, Inferring Meaning: New Cinemas and the Film Festival Circuit.” Film Quarterly, vol. 47, no. 3, 1994, pp. 16–30.

51. Prasch, Thomas. “Embrace of the Serpent. Film Review.” Film & History, vol. 46, no. 2, 2016, pp. 93–5.

52. Pratt, Mary Louise. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. Routledge, 1992.

53. Rabbit-Proof Fence. Directed by Phillip Noyce, Rumbalara Films, 2002.

54. Reiss, Hans, editor. Kant’s Political Writings. Cambridge UP, 1970.

Rony, Fatimah Tobing. The Third Eye: Race, Cinema and Ethnographic Spectacle. Duke UP, 1996.55. Rushdie, Salman. Imaginary Homelands: Essays and Criticism 1981–1991. Granta, 1991.

56. Rovisco, Maria. “Towards a Cosmopolitan Cinema: Understanding the Connection between Borders, Mobility and Cosmopolitanism in the Fiction Film.” Mobilities, vol. 8, no. 1, 2012, pp. 148–65.

57. Rooney. David. “Tanna. Venice Review.” Hollywood Reporter, 9 Aug. 2015, www.hollywoodreporter.com/review/tanna-venice-review-820900.

58. Rosaldo, Renato. “Imperialist Nostalgia.” Representations, vol. 26, 1989, pp. 107-22.

59. Santaolalla, Isabel, editor. “New” Exoticisms: Changing Patterns in the Construction of Otherness. Rodopi, 2000.

60. Segalen, Victor. Essay on Exoticism: An Aesthetics of Diversity. Translated and edited by Yaël Rachel Schlick, Duke UP, 2002.

61. Sexton, Jamie. “The Allure of Otherness: Transnational Cult Film Fandom and the Exoticist Assumption.” Transnational Cinemas, vol. 8, no. 1, 2017, pp. 5–19.

62. Shapiro, Ron. “In Defence of Exoticism: Rescuing the Literary Imagination.” “New” Exoticisms: Changing Patterns in the Construction of Otherness, edited by Isabel Santaolalla, Rodopi, 2000, pp. 41–9.

63. Shaw, Deborah. “Falling into The Embrace of the Serpent.” Mediático, 21 July 2016. reframe.sussex.ac.uk/mediatico/2016/07/21/embrace-of-the-serpent/.

64. Skrbiš, Zlatko, and Ian Woodward. Cosmopolitanism: Uses of the Idea. Sage, 2013.

65. Slater, Candance. Entangled Eden: Visions of the Amazon. U of California P, 2002.

66. Tabu: A Story of the South Seas. Directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, Murnau-Flaherty Productions, 1931.

67. Tanna. Directed by Bentley Dean and Martin Butler, Contact Films, 2015.

68. Tanna Press Kit. 2015. drive.google.com/file/d/0B-FeO1sPBTRNa1RQelJOWHp5dUU/view. Accessed 1 May 2016.

69. Ten Canoes. Directed by Rolf de Heer and Peter Djigirr, Cyan Films, 2006.

70. Viatori, Maximilian. “Re-imagining Amazonia.” Focaal: European Journal of Anthropology, no. 53, 2009, pp. 117–22.

71. Werbner, Pnina. “Vernacular Cosmopolitanism.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 23, no. 2–3, 2006, pp. 496–8.

Whale Rider. Directed by Niki Caro, South Pacific Pictures, 2002.

Suggested Citation

Berghahn, D. (2017) ‘Encounters with cultural difference: cosmopolitanism and exoticism in Tanna (Martin Butler and Bentley Dean, 2015) and Embrace of the Serpent (Ciro Guerra, 2015)’, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 14, pp. 16–40. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.14.01.

Daniela Berghahn is Professor of Film Studies in the Media Arts Department, Associate Dean for Research and Director of the Humanities and Arts Research Centre at Royal Holloway, University of London. She has widely published on postwar German cinema, the relationship between film, history and cultural memory and migrant and diasporic cinema in Europe. Her publications include Head-On (BFI, 2015), Far-Flung Families in Film: The Diasporic Family in Contemporary European Cinema (Edinburgh UP, 2013), European Cinema in Motion: Migrant and Diasporic Film in Contemporary Europe (coedited with Claudia Sternberg, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010) and Hollywood Behind the Wall: The Cinema of East Germany (Manchester UP, 2005).