Women and Media in the Twenty-First Century

Editorial

Abigail Keating and Jill Murphy

Introduction

In a 2015 article on “Tweeting to Empower”, Karen Hua of Forbes Magazine argued that “digital culture has had a huge influence on the push for global gender equality”. This idea has been taken up most recently in a series of articles that marked the tenth anniversary of Twitter’s inception; one such being Zeba Blay’s “21 Hashtags that Changed the Way We Talk About Feminism” in The Huffington Post, which recounts the mechanics of the platform beyond its social value and suggests it “has shaped conversations about women’s issues and [that] feminism has had an unprecedented impact”. In a specifically film and screen media context, one need only look to the “hashtivism” of campaigns such as #AskHerMore and #FavWomanFilmmaker to see not only how the topic of female representation in and across media is gaining increasing momentum within popular discourse, but also how the subject of female representation is, by virtue of the need for such activism, an inherently sociopolitical issue.

In 1995, Rosalind Gill and Keith Grint posed the question, “Are technologies implicated in women’s oppression or could they play a part in women’s liberation?” (1). Like the question, the contemporary answer to this is twofold. Since the beginning of the millennium, technological changes in screen media have been incalculable. The digital turn has, on the one hand, been criticised for generational overconsumption, the Orwellian nature of Web 2.0, the accessibility of pornography, the growing culture of over-sexualisation, and the black market of online download, thus presenting unique challenges both for gender representation and for traditional media. However, it has, on the other hand, been lauded as an era of democratisation—of borderlessnesss in the realm of access to and exposure on new media. Not only has the latter contributed to an increasing awareness of the power of media, but it has also highlighted, to arguably its greatest extent, the global gender imbalance and prejudices that exist within contemporary production and representation.

Women Across Media

One of the ways in which this awareness has been most significantly manifested is in a cross-media context. A striking video entitled “How the Media Failed Women in 2013”, produced by The Representation Project, is a key example of this. The beginning of the video is celebratory in tone, referencing media productions such as Jenji Kohan’s groundbreaking hit Orange is the New Black (2013–present), which has been praised for its diversity in representing women of various ethnicities, sexual orientations and class distinctions, as well as starring the first (openly) trans woman to appear on a Time Magazine cover, Laverne Cox. The initial tone of the video is shortlived, however, as it shifts to an eye-opening montage of media clips—including music videos, advertisements, sports coverage, news footage and online articles—that highlights the severe sexism and brutal misogyny that appears to be embedded in contemporary media. Aside from this startling mashup, the broader project—responsible for the equally powerful 2011 documentary Miss Representation—solidifies the impact that raising these issues in a transmedial way can have. Whatever the form, the same biases and imbalances seem to exist for women in media, and it is with the proliferation of digital technology and culture that a significant, global-reaching, intersectional dialogue has begun.

Figure 1: Kohan's fictional Litchfield prison in Orange is the New Black provides a socially relevant yet symbolic setting through which the show explores the complexities of female identities, relationships and allegiances. Netflix, 2013–Present. Screenshot.

Fundamentally, through greater media attention, as well as constant grassroots exchanges, the dialogue surrounding women in media is now ongoing. For instance, the dominance of (mostly white, male) Hollywood cinema is regularly questioned; recently through the publication of figures on its output during 2014, with just 7% of its highest grossing films directed by women and 85% of all US films directed by men, thus once more bringing into focus the now infamous Hollywood glass ceiling that exists for women behind and in front of the camera. [1] A more recent study surveys 2,000 Hollywood films through their male/female dialogue ratio—the results of which demonstrating the fact that women are underrepresented on all levels in Hollywood cinema. [2]Beyond the heteropatriarchal confines of Hollywood’s dominant ideology, the transnational turn in world cinema, coinciding with the digital turn, has opened up new cross-cultural possibilities for female representation. One prime example can be found in the prominence of Iranian filmmakers and coproductions in the past decade, such as Iranian-French Marjane Satrapi and her French-Iranian-American animated feature Persepolis (2007), based on the graphic novel of the same name, which captures the complexities of the various stages of womanhood against the backdrop of sociopolitical upheaval and transcultural experience. Iranian-American Maryam Keshavarz’s Circumstance (2011) is equally political by virtue of recounting the relationship between two young, queer, Iranian women, and through the film’s production, as it was shot in Lebanon due to the constraints that would have been imposed if shooting had taken place on location in Iran. [3] Gender is also brought to the fore in A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014), Ana Lily Amirpour’s Iranian-American “Vampire Western” that subverts genre tropes and conventional gender dynamics in excessive ways. As such, it has been deemed a protest film, with one commentator arguing that the narrative is “re-imagining Iranian gender politics, and also re-imagining the way Western audiences think about the symbols that go along with them” (Halperin).

Figure 2: A moment of youthful rebellion in Persepolis. Sony Pictures, 2007. Screenshot.

While the diversity and mobility of women’s visions may have increased, accessibility and support is an issue that is still pervasive across borders. The fact that this year’s Cannes’ Sélection Officielle features just eight films helmed by women out of forty-nine in total is another (regular) reminder of an ongoing discrepancy in representation. [4] This has resulted in some notable action being taken recently by film boards and organisations internationally. Bord Scannán na hÉireann/the Irish Film Board’s “Six Point Plan” aims to tackle the underrepresentation of women in Irish film, and in 2015 Eurimages published its “Strategy for Gender Equality” in European cinema. Further, a number of high-profile figures in film are lending their voices to calls for gender parity. Most recently, and widely broadcast, Polish director Agnieszka Holland slammed the hierarchical structure of cinema as a “boys’ club” and suggested that television is a far more female-friendly medium (Child, “Agnieszka Holland”).

Interestingly, much of the discussion surrounding—American, in particular—television in recent years has celebrated it as a “second golden age”, and one need only look to the successes of the aforementioned Kohan, showrunner/producer Shonda Rhimes and writer/director Lena Dunham as examples of how, in productive terms, American television has become a far more progressive medium in relation to gender. [5] Similarly, the last two decades have been marked by a number of significant milestones in the realm of onscreen depictions of women, through shows like Sex and the City (1998–2004) with its “continual foregrounding of a questioning stance that … immediately highlighted its engagement with third-wave feminist politics” (Jermyn 3); The L Word (2004–2009), which sought “to challenge stereotypes and fill a representational void” in the realm of queer female depiction (Akass and McCabe xxvi); and the Rhimes-created/produced shows Grey’s Anatomy (2005–present), Scandal (2012–present) and How to Get Away with Murder (2014–present)—all of which are critically acclaimed, and celebrated for their strong female leads and diversity, particularly through Rhimes’ well-known use of colourblind casting. [6]

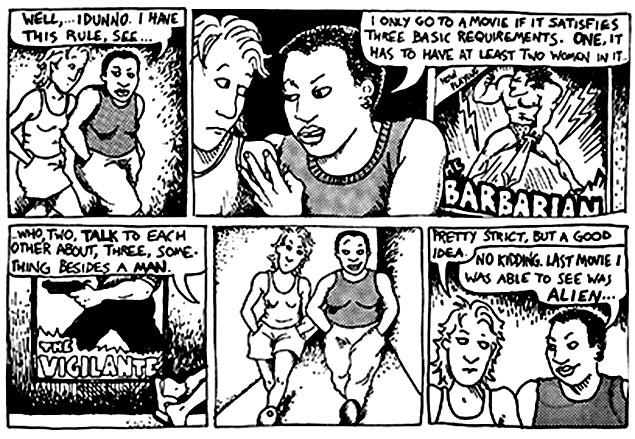

As such, these milestones have contributed to the normalisation of female representation as something that is and should be multifaceted. Further, an increasing normalisation of our own awareness of the underrepresentation of gender diversity and autonomy in media has occurred in contemporary popular discourse to perhaps its greatest extent, again due in large part to the current transnationality and transmediality of media consumption. Key to this is the now widely known Bechdel Test, which stems from Alison Bechdel’s 1985 comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. [7] The three rules of the test, most frequently applied to films but also to video games, television series, comics and theatrical productions, have provided an oft-cited standard in contemporary media criticism against which the merits of a given film (or other production) can be measured in the context of its representation of non-male-led female characters. The popularisation of the Bechdel test in contemporary culture has been significant in exposing the rather dismal amount of theatrically released films that actually pass it.

Figure 3: Origins of the Bechdel Test. Excerpt from Alison Bechdel’s comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For. Firebrand Books, 1986. Screenshot.

Indeed, it seems for every gain made there is another reminder of how much more needs to be achieved. The openness of contemporary screen media has also proved to be fertile ground for manifesting new forms of inequalities. A good example of this is provided by 2014’s GamerGate, a video game controversy that brought gender and the media industry—an especially masculinist industry—into scrutiny in a most graphic, disturbing way. [8] Most specifically, as Chess and Shaw have argued, GamerGate was a controversy reflective of “the sexism, heterosexism, and patriarchal undercurrents that seem to serve as a constant guidepost for the video game industry” (208). Curiously, this also brought into focus the fact that what was once considered a niche area, is now a “mass medium that appeals to all ages and genders … with the genders almost reaching parity” (Todd 64). Further, it raised important questions on social media, on the challenges faced by women working in the media industry, on issues of privacy in the digital age, and on the dangers and effects of cyberbullying and harassment, bringing to light the worrying reality of a deep-rooted, cross-generational misogyny that exists and seems to flourish within the anonymous spaces of online platforms.

Yet the positive ramifications of the current dialogue should not be overlooked. A recent Kickstarter campaign for the production of a documentary on French filmmaker Alice Guy-Blaché is a particularly special example of the benefits of contemporary transmedial and borderless grassroots exchanges. The project, which was successfully funded, brings the story of the first female film director and first director of a narrative film to a new audience and a new generation. Similarly, Vimeo’s announcement of its “Share the Screen” initiative earlier this year—to “help close the gender gap”—highlights the strides that continue to be made within certain divisions of the media industry. As a key player in the broader phenomenon of contemporary, transnational distribution and democratisation, such a commitment is imperative to raising awareness of the lack of diversity not only within traditional artistic avenues, but also in newer forms of creative expression, underlining the important contribution that digital culture can make towards a more global, inclusive, gender-equal media.

As an international, open access journal that is a product of digital culture, and in celebration of its tenth issue, Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media is proud to introduce this special issue on Women and Media as a reflection of the journal’s enduring interest in, and desire to contribute to, this dialogue. Our aim here is to provide a forum for reflection on some of the most important discussions of women and media, celebrating what has been achieved, making transparent what has yet to be, and offering commentary on some of screen media’s most significant moments in this context since the beginning of the new millennium. There is a predominant focus on fictionalised screen representations in this issue, as well as close attention given to a number of prominent filmmakers and the notion of female auteurship. However, many of the articles are transmedial, and indeed transdisciplinary, in their approaches, taking into account, for instance, critical commentary in journalistic media and the challenges facing the categorisation of female filmmakers, popular discourse, literary connections, the Internet as a platform, and other technological and cultural shifts. The thread that binds these works together is a common goal to expose the many significant ways in which women have contributed to media on and off screen, to interrogate the social, political, cultural, ethnic and generational issues at the heart of this, and to locate these questions under the rubric of key debates on the topic of female representation and creation within our discipline.

Twenty-First Century Perspectives

The collaboration between scriptwriter Elsa Chan and director Herman Yau on two features about women in the Hong Kong sex industry, both based on Chan’s anthropological studies of women in the sex industry in Hong Kong, provides the focus of the issue’s opening article, Gina Marchetti’s “The Gendered Politics of Sex Work in Hong Kong Cinema: Herman Yau and Elsa Chan (Yeeshan)’s Whispers and Moans and True Women for Sale”. Marchetti looks at how the two films deal with issues of social justice and the role of women as exploited victims and potential agents of change. She suggests that Chan’s two scripts offer a critical perspective on the circulation of women across borders and point to a feminist intervention in the shadow economy that exists between transnational capitalism and the socialist marketplace in China.

In her article, “Girlhood, Postfeminism and Contemporary Female Art-House Authorship: The “Nameless Trilogies” of Sofia Coppola and Mia Hansen-Løve”, Fiona Handyside considers the unnamed female coming-of-age trilogies of both Sofia Coppola and Mia Hansen-Løve. She proposes that these trilogies of girlhood are simultaneously postfeminist and post-feminist: part of a cinema environment shaped by postfeminist cultural norms while self-consciously performing female cinematic auteurship in full awareness of their coming after (or post) feminist theorising of what it means for a woman to make films. The complexities inherent in such works are examined: in particular the creative power and autonomy of the post-feminist auteur and, in contrast, the narrow, girlish worlds the trilogies depict, which highlight ongoing restrictions for women within postfeminist cultural norms.

In “Femininity, Ageing and Performativity in the Work of Amy Heckerling”, Frances Smith provides a close reading of the cinema of writer/director Amy Heckerling, most specifically of her two most recent films, I Could Never Be Your Woman (2007) and Vamps (2012). Smith considers both films in the context of representations of the female body and current postfeminist media culture, as well as through Judith Butler’s theorisation of performativity. Along with reflecting on Heckerling’s catalogue as genre cinema and her working and reworking of generic tropes, Smith argues that the often subtle complexity of the director’s work merits unpacking in light of her subversion of conventional gender representations and her treatment of mediatised constructions of femininity, ultimately calling for Heckerling to be repositioned as an important feminist voice in contemporary screen media.

Fiona Clancy’s “Motherhood in Crisis in Lucrecia Martel’s Salta Trilogy” considers the Argentine director’s work from the perspective of her exploration of familial relationships, the breakdown of the family unit, and the simultaneities at the heart of her approach. Clancy begins by recounting how generational trauma and the theme of motherhood have been important features of the social and cultural imaginary of Argentina since the last military dictatorship, as well as positioning Martel’s work within this context. Through deep textual analysis and a meticulous consideration of Martel’s use of sound, Clancy argues that the trilogy presents a critique of patriarchal motherhood, yet does so without offering alternative forms of maternal agency, instead paradoxically subverting the notion of biological motherhood while conceptualising mother-child relationships within bodily experience.

Andrea Virginás’s article, “Female Stardom in Contemporary Romanian New Wave Cinema: Unglamour?”, contrasts the filmic performances and nonfilmic appearances of three Romanian New Wave actresses. She posits what she terms their “unglamorous female stardom” as paradoxical when considered from a mainstream/dominant cinema perspective. Using existing star models and theories of national cinema, Virginás examines the concept of unglamorous female stardom as a real-life discursive construct that is dependent on both the production context of the Romanian New Wave, within the framework of small national European cinemas, and postcommunist female public identities.

“‘Nice White Ladies Don’t Go Around Barefoot’: Racing the White Subjects of The Help” by Marie Alix Thouaille examines the extent to which The Help (Tate Taylor, 2011) trades on the “invisibility” and privilege of its white female characters to inhabit, and, appropriate from, the females of colour both within the narrative and in the real life situation from which it originates. Thouaille suggests that women of colour are erased and excluded by a continuing cultural reluctance to “see” whiteness and the privileges it confers in American society. She proceeds to examine how the film subtly subverts some of the ways through which the original literary text equates whiteness with neutrality and humanity, which gives rise to the white middle-class condition being presented as a default subject position for women.Sydney Freeland’s narrative feature Drunktown’s Finest (2014) is the predominant focus of Sophie Mayer’s article “Pocahontas No More: Indigenous Women Standing Up for Each Other in Twenty-First Century Cinema”. Here, Mayer reflects on the representation of Indigenous women over the last two decades and how twenty-first century Indigenous feminist cinema emerges from decades of collaborative practices, located between Third cinema and auto-ethnographic filmmaking. She goes on to present her case study in the context of the figure of Pocahontas and contemporary Indigenous filmmaking and online activism, making a number of striking observations on the historical figure, and pointing to the reappropriation of and recurrent tropes in her representation through various media. She argues that Drunktown’s Finest is not just a counter-appropriation of Pocahontas, but a significant indigenisation, wherein Freeland provides a corrective to the notion of indigeneity as being patriarchal.

Ciara Barrett’s “The Feminist Cinema of Joanna Hogg: Melodrama, Female Space, and the Subversion of Phallogocentric Metanarrative” provides a fascinating scholarly alternative to the current positioning of the British director’s work, establishing a feminist theoretical framework that contravenes the existing phallogocentric critical discourses, which ultimately locate Hogg in the traditions of auteurist cinema. The latter is discussed most predominantly through a consideration of journalistic criticism on Hogg’s work, before Barrett turns her attention to a reading of each of Hogg’s three feature films from the perspective of the director’s iconographic and ideological employment of certain melodramatic conventions, her construction of “female spaces”, and her practicing of a fundamentally feminist cinema.

Concluding the issue, Beti Ellerson’s special report, “African Women of the Screen at the Digital Turn”, provides a valuable insight into the activities of African women in film and screen media. Ellerson surveys the work currently being produced by female African practitioners both on the continent and in the diaspora and considers how it has evolved, developed and transformed through the Internet and the emergence of social media.

The range of articles presented in this issue offers an insight into the expanded spectrum of work by and about women in the new millennium, which springs from perspectives that are, variously, feminist/postfeminist, intersectional, postcommunist, postcolonial, and postcinematic. We hope that this issue contributes to the dialogue on Women and Media in the Twenty-First Century by providing a snapshot of the multifaceted ways in which women are working and being represented across the globe.

Notes

[2] For instance, as the results indicate: “In 22% of our films, actresses had the most amount of dialogue (i.e., they were the lead). Women are more likely to be in the second place for most amount of dialogue, which occurs in 34% of films. The most abysmal stat is when women occupy at least 2 of the top 3 roles in a film, which occurs in 18% of our films.” See full results here: http://polygraph.cool/films/.

[3] See Rohter.

[4] See “Cannes 2016 To Feature Only Eight Films By Women”.

[5] For instance, see Lawson.

It is also worth noting how cross-medial each of the three examples’ work is, through their use of social media as is the case most interestingly with Rhimes, their work in new media outlets as is the case most strikingly with Kohan and her Netflix-produced literary adaptation Orange is the New Black, along with Dunham’s all-rounder status working in film, television, podcasts and literature, as well as having a prominent voice online.[6] Again, it is worth highlighting the transmediality of these shows: Sex and the City as a literary adaptation, which then went on to be adapted into two films; and The L Word, whose final season was complemented by a series of short videos, thematically related to the final episode and released through its network Showtime’s website. As noted briefly above, Anna Everett, in her recent analysis of Scandal, has suggested of Rhimes’ shows that they are “game-changing, ratings-grabbing, and social media-innovating” (34), documenting the strong marketing campaigns that accompany each new season and episode.

[7] In sum, the Bechdel Test requires that: a movie has at least two women in it, who talk to each other, about something besides a man.

[8] For an overview of GamerGate, see Todd.

References

1. Akass, Kim and Janet McCabe. “Preface.” Reading the L Word: Outing Contemporary Television. Ed. Akass and McCabe. London: IB Tauris, 2006. Xxv–xxxi. Print.

2. Bechdel, Alison. Dykes to Watch Out For. New York, Firebrand Books, 1986. Print.

3. “Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché.” Kickstarter. 27 July 2013. Web. 1 March 2016. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/benatural/be-natural-the-untold-story-of-alice-guy-blache.

4. Blay, Zeba. “21 Hashtags That Changed the Way We Talk about Feminism.” Huffington Post. 21 Mar. 2016. Web. 22 Mar. 2016. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/21-hashtags-that-changed-the-way-we-talk-about-feminism_us_56ec0978e4b084c6722000d1.

5. “Cannes 2016 to Feature Only Eight Films by Women.” Women in Film and Television UK. Web. 15 Apr. 2016.

http://www.wftv.org.uk/news/cannes-2016-feature-only-eight-films-women-108624?utm_content=buffer3c04d&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter.com&utm_campaign=buffer.6. Child, Ben. “Agnieszka Holland Says Cinema Is a ‘Boys’ Club’ That Ignores Women.” The Guardian. 14 Apr. 2016. Web. 14 Apr. 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/apr/14/agniesza-holland-cinema-a-boys-club-which-ignores-women.

7. Child, Ben. “Women Are ‘Directors on Just 7% of Top Hollywood Films’.” The Guardian. 27 Oct. 2015.Web. 1 Mar 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/oct/27/women-directors-hollywood-female-filmmakers-gender-bias.

8. Circumstance. Dir. Maryam Keshavarz. Roadside Attractions, 2011. DVD.

9. Drunktown’s Finest. Dir. Sydney Freeland. Indion Entertainment Group, 2014. Film.

10. Everett, Anna. “Scandal, Social Media, and Shonda Rhimes' Auteurist Juggernaut.” The Black Scholar: Journal of Black Studies and Research 45:1 (2015). 34–43. tandfonline.com. Web. 1 Mar. 2016. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00064246.2014.997602?journalCode=rtbs20.

11. “Eurimages and Gender Equality.” Web. 1 March 2016. http://www.coe.int/t/dg4/eurimages/gender/gender_en.asp.

12. “Gender Equality Six Point Plan.” Web 1 March 2016. http://www.irishfilmboard.ie/irish_film_industry/news/Statement_from_the_IFB_on_Gender_Equality_Six_Point_Plan/2975.

13. Gill, Rosalind, and Keith Grint. “Introduction.” The Gender-Technology Relation: Contemporary Theory and Research. Ed. Gill and Grint. London: Taylor & Francis, 1995. 1–28. Print.

14. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night. Dir. Ana Lily Amirpour. VICE Films, 2014. DVD.

15. Grey’s Anatomy. ShondaLand, 2005–Present. Television.

16. Halperin, Moze. “‘A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night’ Is a Protest Film… If You Want It to Be.” Flavorwire. 25 Nov. 2014. Web 1 Mar. 2016. http://flavorwire.com/490408/a-girl-walks-home-alone-at-night-is-a-feminist-protest-film-if-you-want-it-to-be.

17. The Help. Dir. Tate Taylor. Dreamworks, 2011. Film.

18. How to Get Away with Murder. ABC and ShondaLand. 2014–Present. Television.

19. Hua, Karen. “Tweeting to Empower: Feminist Hashtags 2015.” Forbes. 3 June 2015. Web. 1 Mar. 2016. http://www.forbes.com/sites/karenhua/2015/06/03/tweeting-to-empower-feminist-hashtags-2015/#6dc8e09f627e.

20. I Could Never Be Your Woman. Dir. Amy Heckerling. High Fliers Films Ltd., 2007. DVD.

21. Jermyn, Deborah. Sex and the City. Michigan: Wayne State UP, 2009. Print.

22. Lawson, Mark. “Are We Really in a ‘Second Golden Age’ for Television?” The Guardian. 23 May 2013. Web. 1 March 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/tvandradioblog/2013/may/23/second-golden-age-television-soderbergh.

23. The L Word. Showtime, 2004–2009. Television.

24. Miss Representation. Dir. Jennifer Siebel Newsom and Kimberlee Acquaro. Girls' Club Entertainment, 2011. DVD.

25. Orange is the New Black. Netflix, 2013–Present. Television.

26. Persepolis. Dir. Marjane Satrapi and Vincent Paronnaud. Sony Pictures Classics, 2007. DVD.

27. The Representation Project. Web. 1 March 2016. http://therepresentationproject.org.

28. The Representation Project. “How the Media Failed Women in 2013.” Online Video Clip. YouTube. YouTube, 3 December 2013. Web. 1 March 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NswJ4kO9uHc.

29. Rohter, Larry. “Living and Loving Underground in Iran.” New York Times. 19 Aug. 2011. Web. 1 Mar. 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/08/21/movies/circumstance-a-film-of-underground-life-in-iran.html?_r=0.

30. Scandal. ABC and ShondaLand, 2012–Present. Television.

31. Sex and the City. HBO, 1998–2004. Television.

32. “Share the Screen.” Vimeo. 21 January 2016. Web. 1 March 2016. https://vimeo.com/blog/post/share-the-screen-our-pledge-to-female-filmmakers.

33. Shira, Chess and Adrienne Shaw. “A Conspiracy of Fishes, or, How We Learned to Stop Worrying about #GamerGate and Embrace Hegemonic Masculinity.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 59:1 (2015). 208–20. tandfonline.com. Web. 1 Mar. 2016. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08838151.2014.999917.

34. Todd, Cherie. “GamerGate and Resistance to the Diversification of Gaming Culture.” Women's Studies Journal 29:1 (2015). 64–7. ProQuest. Web. 1 Mar. 2016.http://search.proquest.com/openview/84a78c9b3bce39c10955efcccc20a198/1?pq-origsite=gscholar.

35. True Women for Sale [性工作者2 我不賣身.我賣子宮]. Dir. Herman Yau. Screenplay by Herman Yau and Yang Yeeshan. Mei Ah Entertainment, 2008. DVD.

36. Vamps. Dir. Amy Heckerling. Metrodome Distribution Ltd., 2012. DVD.

37. Whispers and Moans [性工作者十日談]. Dir. Herman Yau. Screenplay by Herman Yau and Yang Yeeshan. Mei Ah Entertainment, 2007. DVD.

Suggested Citation

Keating, A. and Murphy J. (2015) 'Women and media in the twenty-first century', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 10, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.10.00.

Abigail Keating is Lecturer in Contemporary Film and Media at University College Cork. She has published widely on gender and identity in cinema, European cinemas, nonfiction, and media and pop culture, and is a cofounding member of the Editorial Board of Alphaville. Her main research interests lie in the areas of women and media, identity in contemporary cinema, and screen media culture. She is currently working on a book on the topic of control and autonomy in contemporary screen media.

Jill Murphy has published articles, translations and reviews in various journals and edited collections. Her research interests principally focus on the relationship between film and art history, particularly as regards human figuration, and the work of Jean-Luc Nancy with respect to the representation of the body in visual media.