The WHAT IF IT Process: Moving from Story-Telling to Story-Experiencing

Sandra Gaudenzi

The emergent field of what will be referred to here as “interactive factuals” (IFs) has been studied by a variety of scholars (Aston and Gaudenzi; Dovey and Rose; Gantier; Gantier and Labour; Gaudenzi; Gifreu-Castells; Uricchio). [1] Much of my own work has focused on defining the field (Living Documentary, “UX”, “Interactive Documentary”, “User”, “Learn”, “!F Lab”). However, few authors have concentrated on the disruption created by the shift in production methodologies in the sector. In I-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary, Judith Aston, Sandra Gaudenzi and Mandy Rose have dedicated a whole section to the topic of “methods”, with the intent of surveying the existing knowledge in the area and mapping attempts by the professional sector to find best practices in interactive factual production. What emerged is that the rise of hackathon culture, the birth of new training initiatives such as IF Lab (aimed at factual storytellers), Hackastory workshop (aimed at digital journalists) and new university initiatives are all clear indications of the need to expose storytellers and content creators to new production praxis. [2] The commonalities among these initiatives are the three main practices needed in an IF team: storytelling, design thinking and agile development. [3] Since IFs are stories that run on a digital interface, in order to produce them one needs to combine expertise in narratology, graphic and interactive design and coding. As I argued in a previous article, adjusting to this new production praxis and authorial power structure is particularly difficult for filmmakers when moving into the interactive field (“User Experience”). Not only do they have to learn to work with people coming from disciplines that are new to them, they also have to let go of the idea that video content is the main way to convey meaning and adjust to the fact that their former (passive) audiences are now becoming active contributors to their work, and therefore gaining decisional power that they did not have before.

Because of the relative novelty of this shift in production praxis, scholars’ attention has so far concentrated on mapping and describing such new methodologies rather than evaluating them (Linington; Pringle; Weiler). Some interactive authors have shared their own production processes through interviews and articles (see in particular the production case studies published by MIT’s Docubase website, but as of yet there have been no studies proposing best practice or new frameworks.

Within this context, this article will address this gap by formalising a methodological framework for interactive narrative development. Following a research project that commenced in 2014, the i-Docs UX Series where I had observed a clear resistance by interactive documentary makers to incorporate design practices in their work process (Gaudenzi, “User Experience”), I created IF (Interactive Factual) Lab in 2015 as the basis of an action research study. IF Lab is a hands-on workshop where storytellers are guided through the development of their interactive projects. During the course of its first three years of iterative existence, IF Lab has tested current agile development, design and creative methodologies in order to produce its own methodology, the WHAT IF IT process. This article first explains the process and its creation, and then assesses its usefulness through interviews and surveys with the participants and coaches of the 2017 IF Lab (the third edition of the Lab).

Two online qualitative surveys were designed for this assessment: the first was sent one week after the completion of the workshop, and was aimed at understanding which parts of the process had been useful to the participants. The second survey was compiled eight months after the completion of the workshop, a period of time that was judged long enough to assess which parts of the process were still used by the participants, if any. Finally, a recorded debrief meeting was held with the coaches that had helped the participants during IF Lab 2017, with the aim of assessing the quality of the projects and the usefulness of the WHAT IF IT process in facilitating their development.The results of this threefold feedback process are disclosed in this article with three main research questions in mind: first, to assess the WHAT IF IT methodology and its specific mix of design, agile and storytelling approaches; second, to treat the WHAT IF IT process as a prototype, and reflect on how it could be improved; third, to start formalising a methodological framework for interactive narrative development.

From Audiences to Users in IFs

Before moving into the particularities, and assessment, of the WHAT IF IT methodology, it might be necessary to give some context to the field of IFs (Interactive Factuals), also referred to as i-docs (interactive documentaries), and to the consequent shift from the notion of audiences to users. [4] In an article co-written with Judith Aston, “Interactive Documentary: Setting the Field”, we begin with an early definition of interactive documentary from Dyana Galloway as “any documentary that uses interactivity as a core part of its delivery mechanism” (qtd. in Aston and Gaudenzi 126). We then argue that in digital storytelling “interactivity goes beyond a ‘delivery mechanism’ to become a production mechanism in its own right” (Aston and Gaudenzi 126). We also claim that the moment the linearity of reception is replaced by a logic of interaction, “it creates a different dynamic between the user, the author, the artefact and its context, that affords a range of constructions of ‘realities’” (126). Interactivity is seen as a dynamic that moves the documentary form from the logic of an author creating for an audience to a “living documentary” (Gaudenzi, “Living Documentary”), where each receiver is active in constructing its own narrative and, by doing so, becomes both a user and a co-author of such narrative (Gaudenzi, “User Experience”). In the new paradigm of interactive narratives, one could therefore say that one does not create for an audience, but with its users.

Since the digital product relies on the collaboration of its users in order to “become alive” (if they do not interact with it, it does not create itself and does not unfold) “designing functional user-friendly interfaces and understanding both the design and perceived affordances and constraints of the digital technologies are essential for creating user comprehension and satisfaction” (O’Flynn 74). In other words, digital technologies come with their affordances and with a history of interaction design processes. Back in 2014, former National Film Board of Canada chairman Tom Perlmutter argued in his provocative article “The Interactive Documentary: A Transformative Art Form” that:

The importance of understanding and relating to audiences tends to elicit an almost offended reaction [from filmmakers]: “I am making my film. I am not going to be dictated to by what an audience wants. After all, this is art, not paint by numbers.” To take this attitude is to misunderstand profoundly what understanding audience means in an interactive world, where as creator you make the audience a collaborator in your processes. This does not invalidate the filmmaker as creator or auteur. It enlarges the notion of auteur. The new auteurs will understand that the relationship to audience as co-creators and collaborators is part of their medium of creation. (Emphasis added.)

It is precisely with the intention to explore this new collaboration between authors and users described by Perlmutter that the IF Lab workshop was created. The aim was to help filmmakers transitioning from traditional narrative practices to interactive storytelling ones.

IF Lab

IF Lab is a training workshop supported by Creative Europe that started in 2015. It aims at developing interactive storytelling projects by moving them from concept to digital prototypes. Each year, IF Lab selects up to twelve interactive ideas and helps their creators transform them into digital projects through two workshops of five days each. [5] The first workshop, Story Booster, concentrates on concept development while the second, Prototype Booster, on the creation of a digital prototype.

Figure 1: IF Lab 2017 Promo. Courtesy of iDrops.

IF Lab is coordinated by iDrops, a Belgian social innovation agency, and facilitated by myself, with the help of rotating industry practitioners. Each year a core team of three coaches is selected for their expertise in the field of design, storytelling and coding. This core team follows the projects throughout the two workshops while other industry guests might be invited for a shorter period to share their specific knowledge and personal projects.The first two years of IF Lab served as an experimental sandpit where different industry practices were mixed to help incubate the participants’ projects. By the third year, a clearer methodology started to emerge and it was decided to start formalising it by giving it a name, the WHAT IF IT process, and a structure.

The WHAT IF IT Process

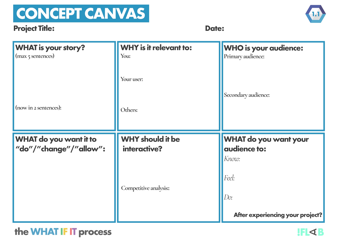

The WHAT IF IT process is an evolving methodology that mixes design, coding and storytelling practices following the evolution of industry expertise. As a process it is highly inspired by Design Thinking and User-Centred Design and is composed of five main phases: WHAT is your concept, Iterate it, Formulate it, Ideate and prototype, and Test (WHAT IF IT). [6]

Figure 2: The five phases of the WHAT IF IT process. IF Lab.

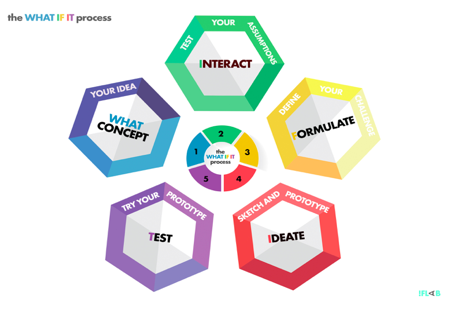

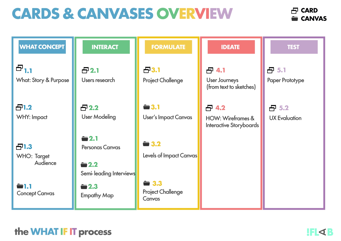

In order to help participants to move through these five phases, it was decided to create a series of “cards” and “canvases”. The cards are mini-lectures, while the canvases are ready-made schemas that facilitate teams’ decision-making, effectively helping them to move from theory to practice within their own project. [7]

Figure 3: Cards and canvases overview—as they were in 2017. IF Lab.

Figure 4: Example of Canvas—the “Concept Canvas”. IF Lab.

The first workshop, Story Booster, uses five days to go through the iterative ideation process. [8] Participants are led through a process that challenges their initial concept by starting from the aim and target audience of the project, rather than from the story itself. On day one, participants are asked to introduce their ideas while the whole group collaborates by identifying potential issues and inconsistencies. Days two and three are then spent challenging their ideas by filtering through a design process where the target audience is explored, as well as the possible motivations and needs of the users, the added value and potential impact of the project. During and after these discussions, participants are asked to consider possible platforms for dissemination of their work. Day four is spent prototyping possible ideas on paper, and these prototypes are tested on the final day and presented as a solid concept to the whole cohort. When participants leave after the fifth day to go back home they are encouraged to continue working by interacting with their selected target audience and restarting this five-step ideation process by themselves until their idea is fully formed.

For example, a participant that came with a project that explores the closure of a nuclear power station and the impact on the community who live and work in and around the power station, would have been asked in the first two days to decide if the main target audience is the community living around the nuclear power station, or a general public interested in environmental issues. Depending on the decision of the author, a discussion on the best possible platform would follow: a web-based project, a geo-tagged mobile app or an aural tour of the premises? Then, a paper prototype tested by other IF Lab participants would serve as a first feedback opportunity, but the author would be asked to engage with her chosen audience during the two months following Story Booster. Changes to the project interface, structure and content would then be presented at Prototype Boosters, ready for another circle of iterations.

Figure 5: Testing paper prototypes at the end of Story Booster 2017. IF Lab.

The second five-day workshop, Prototype Booster, takes place two months after Story Booster. This workshop advances the projects from a paper to a digital prototype. This phase of the workshop includes a Prototype Jam—a three-day hackathon in which digitally skilled professionals assist the teams that are in need of creative coders and graphic designers. [9] It is clear that the biggest learning curve for storytellers is in the form of acceptance of cocreation within a multi-disciplinary team, and in learning to let go of authorial control in view of a more inclusive and iterative way of working together. Prototype Booster finishes with a pitch of the digital prototypes in front of a panel of three external decision makers invited by IF Lab. These decision makers could have a broadcast or festival commissioning role, or could be interactive producers themselves. There are no prizes to win for the best pitch, but rather an intense feedback session aimed at giving enough information to keep iterating projects before embarking into fundraising and production.

Figure 6: IF Lab described by its participants. Courtesy of iDrops.

Evaluating the WHAT IF IT Process

When considering how to evaluate the WHAT IF IT process it was decided to complete two surveys with the participants and a recorded debrief session with the coaches. The participants’ surveys had a time gap of eight months between the two to counterbalance the novelty effect of the workshop, while the debrief session with the coaches happened one week after the end of Prototype Booster 2017, when memories were still fresh. Evaluating the process from the point of view of both the participant and the coaches allows a dual assessment: the participants find it easier to be objective about the process than their own project, while the coaches are more critical of the projects than of the process that they helped create.

For the first survey with the participants a semi-qualitative approach was followed. A Google survey with nine questions was designed and sent to the eight projects that participated to both 2017 IF Lab workshops. The survey was sent one week after the end of IF Lab, giving participants enough time to assimilate the process, but making sure the experience was still fresh in their minds.Six participants (representing six projects out of eight) responded. Their age ranges between twenty-one and forty-nine and they all come from a storytelling background (four documentary filmmakers, one photographer and one academic). They will be referred to as P1 to P6 in this article.

The nine questions of the surveywere geared at understanding how the emphasis on a User-Centred Design (UCD) approach had been experienced by the participants (who all come from linear media practice) and to evaluate in which way it helped them to design an interactive structure for their projects. [10] The questions were not intended to evaluate the quality of the projects, because none of them were fully developed yet, and participants were too involved in them to be able to respond. Therefore, the following results address the felt experience of the methodology from the participants’ point of view. Now that they had all produced a prototype of their ideas, what was their critique of the UCD process that got them there, and would they use it again?

The drawback of this type of written survey is that it could be prone to bias because it was conducted by a representative of the IF Lab team, and not an independent third party. This could induce participants to be more “considerate” while responding. On the other hand, if participants wished to criticise the process, the survey was a safe tool to do so, as the workshop was finished by then. It is with the awareness of the limits of such a qualitative approach that the main results of the survey are discussed in the next session.

Findings of the First Survey

1. The WHAT IF IT Process Forced Participants to Try an UCD Creative Approach

Without the collaborative aspect of the workshop, and the step-by-step methodology employed, participants would not have applied an agile and UCD process to their project. The UCD approach challenges traditional linear content creators in the sense that it puts the user at the centre of the creative process, by asking the author to empathise with the user and give him/her a certain decision-making power (Gaudenzi, “User Experience” 125). Filmmakers coming from an “auteur” praxis where authorial control is prioritised have a more introverted creative process and are not used to considering the audience’s needs as a starting point.

To the question, “Did the fact of having a step-by-step methodology help you in the development of your interactive story”, five out of six participants said “yes”, and one responded “a little”. When asked to elaborate on their answer, the majority of participants stressed the fact that being together in a room and going through the same steps allowed them to challenge themselves into new ways of creating. Examples of comments included:

It helped me reverse, to a certain extent, the way I approach my story in that this system starts from the user rather from the story itself (P4).

It made me challenge my own preconceived ideas (P1).

2. The WHAT IF IT Process Challenged Participants’ Perception of their Role as Storyteller/Author

Inspired by UCD, the WHAT IF IT process uses emotional maps and personas to identify needs (gains) and frustrations (pains) as a starting point of the creative process. Using a problem-solving approach, the role of the author is then to take inspiration from the gains and pains of the user and design an interactive experience that will bring such a user from his/her current level of knowledge, feelings and actions to the desired level of knowledge, feelings and actions (impact). In other words, the “user journey” is designed as a transformational experience that starts where the user is prior to the experience of the project and brings him/her where the author wants him/her to be (aim of the project). [11] In order to design such a journey, participants are requested to engage with their audience through in-depth interviews and map users’ knowledge, frustrations and needs in relation to a chosen topic. Through repetitive interaction with their future users, authors are encouraged to conceive their narratives as a transformative journey that can deliver knowledge, emotions and even confusion, if wished so, to their users. The effect and impact of the interactive story is an artistic decision of the author, the WHAT IF IT process only puts the emphasis on the fact that an author needs to interact with his/her users and test his/her own assumptions if he/she wants to be heard by his target audience.

This solution-driven way of creating was new to most participants, as they normally start from the content they want to shoot, and not by considering the overall concept and impact strategy of the piece:

It’s not about content really—it’s about the “concept”. Which is so difficult for an author-director-storyteller because you are attached to your content-story-characters... and made to push that to the side and think more about the user experience, impact and details that aren't usually part of your thinking when telling a story (P2).

I always go after what I feel it is right not thinking about the audience. I work mostly intuitively, but this time I was thinking about the audience (P4).

The importance given to testing as a way to double-check the validity of a concept was also a novelty and clearly led to a more shared understanding of authorship:

Previous to this, I had never really tested my work in a systematic fashion (P3).

It was strange to be working/developing a project in a collective where no-one is a guru and everyone is adding a piece into the mosaic (P5).

3. Participants Want to Keep Using the WHAT IF IT Process in Future Interactive Projects

Even if the WHAT IF IT methodology was at times quite painful for participants, all participants seemed to accept it as the way forward when designing interactive work. When asked if they would use the methodology in future interactive projects six out of six said “yes”. Maybe because of the “rawness” of the experience at the time of the survey, or out of courtesy, none of the participants criticised the process, and six out of six said that “concentrating on the user experience, and giving slightly less importance to the story itself, was frustrating but necessary”:

The biggest difference is thinking about how someone will be able to interact with the project, and the processes for testing this. This completely changes how I will think about producing future work (P1).

Finally, five out of six participants said that the process made the project “clearer and more coherent to themselves (and their project goals)”.

Evaluation of the WHAT IF IT Process by the Coaches

One week after the end of the workshop, an evaluative debrief session was organised between the three 2017 IF Lab coaches and two workshop coordinators members. [12] Interestingly our assessment was slightly less enthusiastic than that of the participants. Most of us felt that, due to the effort in concentrating on the user, authors nearly forgot about the importance of their story, and designed user journeys that at times seemed to please the process rather than themselves. As a result, some ideas were functioning from a rational point of view, but were lacking the surprise effect of good storytelling. Since the possibilities of interactive structures and platforms can be overwhelming for newcomers, we sometimes had the feeling that participants were “playing it safe” in order to follow the fast pace of the workshop. The nature of fast prototyping pushes people to commit to one idea early on in order to develop it, test it and then move forward. The coaches feared that sometimes participants had stepped back into relatively safe structures of tree-structure navigation (web-doc) in order to follow the methodology.

If one evaluates the learning process of the participants (regardless of the “quality” of their final projects), then it could be claimed that IF Lab is a real success. The vast majority of participants declared having “changed their creative approach” during the workshop. But for IF Lab, the challenge is to evaluate if being exposed to a new way of working has long-term effects and if eventually it has allowed the production of satisfactory projects by the participants. One way to assess if the WHAT IF IT methodology has the right mix of design, agile and storytelling approaches is to check if, and how, it has been used once participants are back into their professional environment. It was therefore decided to reinterview the same six participants eight months after their first survey.

The Results of the Second Survey

Eight months after the end of IF Lab 2017, the six contributors to the first survey were contacted again and asked to answer seven new questions aimed at assessing how much of the WHAT IF IT process was still in their praxis and how their project had evolved. All of them claimed to have used the process again within their ongoing practice. All projects were still in development but one. When asked what part of the process had been more relevant to their current practice, the majority identified it as a way to focus and keep clarity of intent:

I have been using the process mainly as a point of reference, when I feel lost in the process. It helps me to remind me who my target audience is, sharpen my story and the kind of interface I want to develop/design. I have worked across canvases (P5).

Everything I learned and did at IF Lab is relevant to my current practice—and to be honest it’s relevant to life... Learning to mix with other cultures, languages, disciplines and learn to “talk” to each other I FEEL is the BIGGEST accomplishment” (P2; emphasis by participant).

Regarding the evolution of their ideas, it is noteworthy that all of the participants claimed that the current version of their project was “a clear evolution of the idea developed at IF Lab”. This answer is important because it indicates that the learning that happened during the workshop was more than just an opening to a new methodology; it generated creative ideas that were kept eight months later.

These two findings respond to our enquiries about the long-term effects of the methodology learned at IF Lab: participants kept using some canvases and the UCD part of the methodology to evolve the ideas that emerged from the workshop. To assess if participants were satisfied by the evolution of their projects is much more difficult, since none of the projects are, to date, fully completed. What most participants took from the workshop was the possibility of beginning a development process from the user’s needs and focussing on such constraints as a creative methodology. When asked if in their current iteration of the project, they had kept their users’ needs at the centre of the creative process, or rather followed their intuition, they all acknowledged that they had tried to balance both.

Possible Iterations of the WHAT IF IT Process

The challenge for both authors and workshop designers is to get the balance between interface design and engaging storytelling right, while making sure that the use of interactivity is meaningful to the user. By using a UCD structure WHAT IF IT forces linear authors to adopt a more empathic way of working and allows them to keep focus on the user. The emphasis on agile development permits a trial and error approach that delivers solutions. Yet, maybe one praxis has started to overshadow the others. The risk is to go from an author-centred storytelling logic to a user-centred one without finding the right middle ground.

I think design thinking doesn’t take into account the full holistic framework. What I see has been problematic in the past is focusing on what appears to be a problem at hand rather than focusing on the holistic framework that surrounds the area over the problem (McDowell).

The reason we have been applying design thinking to interactive storytelling is because, when we build an interactive interface, we are creating both a digital object and a story experience. Interactive factuals (IFs) often also aim to create some sort of change in society, therefore it is crucially important for authors to think about their audience. UCD therefore becomes a useful proposition as it aims to create digital objects with a function. In this scenario, a focus on structure and form could overshadow narrative creativity. Have we stretched the use of UCD too far in IFs?

Next Steps: Towards an Experience Design Methodology for IFs

If we accept the hypothesis that stories are experiences and just not products, goods or services, then when pondering how to best design them we need to include some notions of experience design. In their article “Welcome to the Experience Economy”, Joseph Pine and James Gilmore argue that experiences engage individuals in a memorable event that is inherently personal, and potentially emotional, physical, intellectual and perhaps even spiritual. Building on this definition, Tara Mullaney points out that designing transformative and memorable experiences demands us to understand experiences as “subjective, holistic, situated, and dynamic by nature” (qtd. in Hassenzahl 9; emphasis in original). If we were to shift our understanding of IFs from story-products to story-experiences, then maybe the emphasis on UCD would need to be mitigated by the introduction of notions of experience design.

Experience design will be understood here as “the discipline of looking at all aspects—visual design, interaction design, sound design, and so on—of the user’s encounter with a product, and making sure they are in harmony” (Saffer 20). For experience designer specialist Marc Hassenzahl, experience “emerges from the intertwined works of perception, action, motivation, emotion, and cognition in dialogue with the world (place, time, people and objects). It is crucial to view experience as the consequence of the interplay of many different systems” (11). While Human Computer Interaction has been primarily concerned with the “what” and the “how” of interaction, because it is easier to test, it has forgotten to consider the “why”. The “why”, for Hassenzahl, is essential because it touches what he calls “be-goals, what effectively make something meaningful to us. […] ‘Being competent’, ‘being close to others’, ‘being autonomous’, and ‘being stimulated’ are examples of be-goals” (12). One can understand them as touching our value system and our deep aspirations. Hassenzahl urges us creators to start from the “why” of a project, which in the context of IFs would mean to start from how the wished impact could trigger an inner value in its audience. While emphasising how the interactor should feel is already part of the design thinking methodology (and of the WHAT IF IT process), Hassenzahl adds an important nuance by focusing on the aspect of “being”. A story about water shortage could have the clear aim (the “why”) for the creator to educate its audience on sustainable living and to create a wish (the “do”) to become water conscious on a daily basis. This is what impact designers call the “why”, the wished result, but this type of “why” does not cover the why-should-the-user-be-touched-by-the-experience, or the which-value-does-this-nurture.

How to introduce, in a development methodology, a part that encourages authors to start from core values (such as self-realisation, esteem, love/belonging, safety, physiological needs etc.) and test if/how they resonate with the user’s need to “be” different, or to improve himself/herself, is not the focus of this article. Nevertheless, this question gives a new direction to the future iterations of IF Lab.

Conclusion

The aim of this article was to assess the effectiveness of mixed methodologies of production for interactive narratives by using the IF Lab workshop as a case study, and to start formalising a methodological framework for interactive narrative development.

From the interviews and surveys that were completed with a sample of IF Lab 2017 participants, one can conclude that using a clear methodology helped creators to quickly advance in an unknown territory. The WHAT IF IT process kept participants focused on the needs of their audience and made them experiment with an inversed process of creation, where ideas emerge from the process of bridging the user’s needs and the author’s desired impact.

Our surveys suggest that following an iterative design process helped participants achieve coherence throughout the different iterations of their project. This model facilitates incremental adjustments towards solving the initial problem, or design question, of each project. Where the design thinking starts being limiting is when it puts too much emphasis on problem solving—as by doing so it risks simplifying complex experiences in order to solve issues. In other words, a solution-driven approach might privilege functionality over value and emotional engagement.

If we want to design transformative experiences we need to keep experimenting towards a more systemic design approach where story and interface and aesthetic do not just deliver a “working product”, but rather an emotional experience that needs to be meaningful to the user by addressing a personal be-goal, or a core value (such as “love yourself”, “find your tribe” or “help those in need”). Moving towards a new framework for interactive narrative development means adding experience design to the current mix of design, agile and narrative methodologies.

Notes[1] Interactive factuals are defined here as “any project that starts with the intention to engage with the real, and that uses digital interactive technology to realize this intention” (Aston, Gaudenzi, and Rose 1). It includes projects that may be described elsewhere as i-docs, web-docs, transmedia documentaries, serious games, locative docs, interactive community media, docu-games and, also, forms including virtual reality nonfiction, ambient literature and live performance documentary.

[2] On the rise of hackathon culture see, for example, POV Hackthons (POV Documentary Blogs), Tribeca Hacks (Tribeca Film Institute), and Popathon (DocsBarcelona). IF Lab was founded in 2015 (!FLAB). On new university initiatives, see Columbia’s Digital Storytelling Lab (Columbia), the Digital and Interactive Storytelling Lab (University of Westminster), and the Transmedia Zone (Ryerson University).

[3] Design thinking is a particular iterative approach to solving problems creatively using a process normally divided in the following stages: defining the problem; research; ideas formulation; prototyping and testing. Agile development is an iterative approach to software development that encourages constant testing of small parts of code to facilitate quick and flexible responses to change.

[4] The history of audience research provides a multitude of definitions of the term (Livingstone). In the context of this article it is important to clarify that, although audiences are never fully passive, for they hold the power of selection and interpretation and choose how to engage within their communities (Srinivas), they nevertheless cannot change the content of the film itself. In contrast, audiences of digital interactive work can be granted such power by the authors, because of the feedback mechanism of interactive interfaces (Gaudenzi, “Living Documentary”) that can allow them to click, add, comment or even create new content. It is because of this active authorial role that they are normally referred to as users or inter-actors.

[5] Over the first three years, fifty-five people from all over the world (mainly Europe, but also four from the USA, two from Israel and one from Saudi Arabia) participated to IF Lab producing a total of twenty-nine projects. The vast majority of the participants come from a linear content background (journalists, documentary makers, photographers and independent producers) with the addition of some academics and a minority of digital creators.

[6] The term User-Centred Design (UCD) is normally attributed to Donald Norman. In his book User Centered System Design he states that “from the point of view of the user, the interface is the system. Concern for the nature of the interaction and for the user—these are the things that should force design. […] User-centered design emphasizes that the purpose of the system is to serve the user, not to use a specific technology, not to be an elegant piece of programming” (61).

[7] A selection of such cards and canvases, including the one pictured in this article, are freely available by downloading the “!F Lab Field Guide to Interactive Storytelling Ideation”.

[8] The ideation process brings the participant from an initial concept that has, for example, been presented on the first day as a project that portrays the stories of LGBTQIA persons of South Asian descent living in the US, to a much more detailed visualisation of the project that includes an interface for a web-documentary, edited video content, a mobile app version and a detailed plan of the content areas to be developed. The iterative nature of such ideation process allows the author to make decisions once the solutions emerge from a circular motion of ideating–prototyping–testing–ideating again.

[9] The term “creative coders” is used by the industry to portray a person with high-level software and coding skills that is also comfortable in an authorial position and wants to be part of the concept creation process.

[10] The nine questions were divided as follows: four multiple-choices, four semi-opened and one open question. Semi-opened questions, such as “Did the fact of having a step-by-step methodology help you in the development of your interactive story? Explain in which way it did/did not help”, were aimed at having the participant reflect on the process in a positive/negative way, while questions like, “Was the fact of starting the creative process from the audience & impact point of view intuitive to you? Please explain” were directing the participant towards assessing how UCD methodologies worked for him/her. Finally, multiple choice questions, such as “Has the fact of producing a prototype & testing it made your project: 1. Clearer and more coherent to the user, 2. Clearer to yourself, 3. Different from what you would have produced alone, 4. More/less creative than if you had done it by yourself, 5. Other answer (fill in option)…”, were designed to encourage the participants to judge the impact of the process on their project.

[11] The user journey is the sequence of choices or events a user might encounter while using an interactive product or service. User journeys are designed and mapped as part of the design process of an interactive project.

[12] Out of the three coaches of IF Lab 2017, two are academics with an industry background and one is an interactive producer. Each of them has an area of expertise (storytelling, design, or coding) but the three have a good overall understanding of the field. The author of this article is one of them. Both the coordinators of IF Lab 2017 are new media maker/producers

References1. Aston, Judith, and Sandra Gaudenzi. “Interactive Documentary: Setting the Field.” Studies in Documentary Film, vol. 6, no. 2, 2012, pp. 125–139.

2. Aston, Judith, Sandra Gaudenzi, and Mandy Rose, editors. I-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary. Columbia UP, 2017.

3. Columbia University School of the Arts. Digital Storytelling Lab, www.digitalstorytellinglab.com. Accessed 15 May 2019.

4. DocsBarcelona. Popathon. 2014, http://www.docsbarcelona.com/en/ed-2015/interdocsbarcelona/popathon. Accessed 15 May 2019.

5. Dovey, Jonathan, and Mandy Rose. “‘This Great Mapping of Ourselves’: New Documentary Forms Online.” The Documentary Film Book, edited by Brian Winston, BFI, 2013, pp. 366–375.

6. Gantier, Samuel. “Le Webdocumentaire, un format hypermédia innovant pour scénariser le réel.” Journalisme en Ligne, edited by Amandine Degand and Benoit Grevisse, Deboeck, 2012, pp. 159–177.7. Gantier, Samuel, and Michel Labour. “User Empowerment and the I-Doc Model User.” User Empowerment: Interdisciplinary Studies and Combined Approaches for Technological Products and Services, edited by David Bihanic, Springer, 2015, pp. 231–254.

8. Gaudenzi, Sandra. The Living Documentary: From Representing Reality to Co-Creating Reality in Digital Interactive Documentary. PhD dissertation, Goldsmiths, U of London, 2013.

9. ---. UX Series. 2014, www.interactivefactual.net/ux-series. Accessed 15 May 2019.

10. ---. “The Interactive Documentary as a Living Documentary.” DOC On-Line, Digital Magazine on Documentary Cinema, Special Edition Webdocumentary, vol. 8, no. 14, 2013, pp. 9–31.

11. ---. “User Experience Versus Author Experience: Lesson Learned from the UX Series.” Aston, Gaudenzi, and Rose, pp. 117–129.

12. ---. “The Learn Do Share Design Methodology: Lance Weiler in Conversation.” Aston Gaudenzi, and Rose, pp. 129–139.

13. ---. “The !F Lab Field Guide to Interactive Storytelling Ideation.” www.iflab.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/the-F-Lab-Field-Guide.pdf. Accessed 9 Feb. 2019.

14. Gifreu-Castells, Arnau. El documental interactivo. Evolución, caracterización y perspectivas de desarrollo. Editorial UOC, 2013.

15. Hassenzah, Marc. Experience Design: Technology for All the Right Reasons. Morgan & Claypool Publishers, 2010.

16. !FLAB: Interactive Facual Lab. 2015, www.iflab.net. Accessed 17 May 2019.

17. Linington, Jess. “Pushing the Craft Forward: the POV Hackathon as a Collaborative Approach to Making an Interactive Documentary.” Aston, Gaudenzi, and Rose, pp. 139–154.

18. Livingstone, Sonia. “The Participation Paradigm in Audience Research.” Communication Review, vol. 16, no. 1–2, 2013, pp. 21–30.

19. MIT OpenDocumentary Lab. Docubase. www.docubase.mit.edu. Accessed 16 May 2019.

20. McDowell, Alex. “World Building and Narrative.” Lynda.com, 10 Sept. 2015, www.lynda.com/3D-Animation-Architecture-tutorials/Alex-McDowell-World-Building-Narrative/362994-2.html.

21. Norman, Donald. User Centered System Design: New Perspectives on Human–Computer Interaction. CRC Press, 1998.

22. O’Flynn, Siobhan. “Designed Experiences in Interactive Documentaries.” Contemporary Documentary, edited by Daniel Marcus and Selmin Kara, Routledge, 2016, pp. 72–86.

23. Pelmutter, Tom. “The Interactive Documentary: A Transformative Art Form.” Policy Options, 2 Nov. 2014, policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/policyflix/the-interactive-documentary-a-transformative-art-form.

24. Pine, Joseph, and James Gilmore. “Welcome to the Experience Economy.” Harvard Business Review, vol. 4, July–August, 1998, pp. 97–105.

25. POV Documentary Blogs. POV Hackathons. 2014, www.archive.pov.org/blog/povdocs/2014/05/pov-hackathon-6-the-projects/. Accessed 15 May 2019.

26. Pringle, Ramona. “Testing and Evaluating Design Prototypes: The Case Study of Avatar Secrets.” Aston, Gaudenzi, and Rose, pp. 154–170.

27. Ryerson University. Transmedia Zone. www.transmediazone.ca. Accessed 15 May 2019.

28. Rose, Mandy. “Making Publics: Documentary as Do-It-with-Others Citizenship.” DIY Citizenship: Critical Making and Social Media, edited by Matt Ratto and Megan Boler, MIT Press, 2014, pp. 201–212.

29. Saffer, Dan. Designing for Interaction: Creating Innovative Applications and Devices. New Riders, 2010.

30. Snyder, Carolyn. Paper Prototyping: The Fast and Easy Way to Design and Refine User Interfaces. Morgan, 2003.

31. Srinivas, Lakshmi. “The Active Audience: Spectatorship, Social Relations and the Experience of Cinema in India.” Media, Culture & Society, vol. 24, no. 2, 2002, pp. 155–173.

32. Tribeca Film Institute. Tribeca Hacks. www.tfiny.org/pages/tribeca_hacks_about. Accessed 15 May 2019.

33. University of Westminster. Digital and Interactive Storytelling Lab MA. . Accessed 15 May 2019.

34. Uricchio, William. “Things to Come; the Possible Futures of Documentary… from a Historical Prospective”. Aston, Gaudenzi, and Rose, pp. 191–206.

Suggested Citation

Gaudenzi, Sandra “The WHAT IF IT Process: Moving from Story-Telling to Story-Experiencing.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, no. 17, 2019, pp. 111–127. https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.17.07.

Sandra Gaudenzi is an expert in interactive narratives. She has been consulting, mentoring, researching, lecturing, writing, speaking and blogging about interactive factual narratives for the last twenty years. She is Senior Lecturer at the University of Westminster in the new Digital and Interactive Storytelling LAB MA; Visiting Fellow at the Digital Cultures Research Centre (UWE, UK) where she codirects the i-Docs conference, and with whom she coedited her recent book I-Docs: the Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary. She is also Head of Studies of !F Lab, a professional training scheme for the ideation of factual interactive stories.